- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

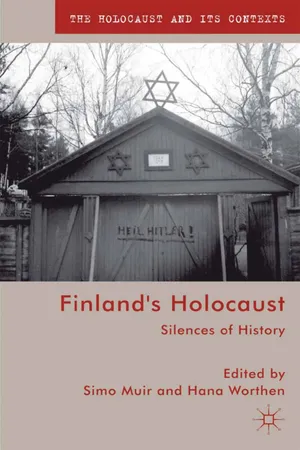

Finland's Holocaust considers antisemitism and the figure of the Holocaust in today's Finland. Taking up a range of issues - from cultural history, folklore, and sports, to the interpretation of military and national history - this collection examines how the writing of history has engaged and evaded the figure of the Holocaust.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Finland's Holocaust by S. Muir, H. Worthen, S. Muir,H. Worthen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Contesting the Silences of History

Finland’s Holocaust: Silences of History pursues two interlocking goals. The first is to trace the implications of antisemitism in Finland from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries through Finland’s alliance with the Third Reich during much of World War II to the complex negotiation with its wartime past controversially emerging in contemporary historiography. In the second, by taking up a range of issues—from cultural history, folklore, the arts, and sports, to the interpretation of military and national history—this collection examines how the writing of history and modern Finnish memory have both engaged and evaded the figure of the Holocaust since the war. Unpacking the nexus of the German–Finnish World War II alliance, often described as a strategic necessity, and long-standing patterns of German–Finnish cultural affiliation colored by the rhetoric of race in the 1930s and 1940s, the anthology turns its attention to the practices and constructs of Finnish academia and society that have worked to displace the narrative of antisemitism from Finnish history. In an important sense, the aim of the anthology is to analyze these varied modes of displacement; as silent and silenced histories, they, too, sustain a prominent strain of historical writing, or, better, sustain its lack of perceptive models for a more complex understanding of antisemitism in Finland.

Paradigms of separation

Aiming to examine historical and contemporary events, institutional and political discourses, censorship practices, and memories as a way to rethink and to particularize the trope of “Finland’s Holocaust” in the national and international context, this collection of essays diversifies the terms of the national narrative of modern Finnish history. Finland’s Holocaust arises from the critique of the normative “separation narrative” of Finland’s participation in World War II. With regard to military and political history, this paradigm—having been subjected to critique by professional historians since the 1980s—might seem dated. And yet, as the collection at hand argues, separation continues to provide a significant paradigmatic resource in academic analysis across fields of historical and cultural representation. Although Finland became an ally of the Third Reich during their joint attack on the Soviet Union in the so-called Continuation War (1941–44), Finnish historical culture has conventionally imagined the Holocaust as an isolated event, an affair and an arrangement of the Third Reich separate from its military “co-belligerence.” This principle of “separation” has had far reaching effects, sustaining the warrant for disacknowledging antisemitism as an element of Finnish culture, for dismissing possible mistreatment of Jews in Finland during the Finnish alliance, including those Jewish refugees extradited to Germany, and for repudiating the entanglement with the racialized Kultur promoted by the Third Reich. Rather than merely proposing a corrective to this exclusionary history and historiography, Finland’s Holocaust proposes an elaboration both of the narrative of Finland’s past and of the rhetorical structures of Finnish historiography, aiming to subject the unified national narrative both to a plurality of perspectives and to the heterogeneity of scholarly expertise.

The discourses of separation are rooted in the consensual interpretations of Finland’s role in the Second World War, which vary from fighting its own “separate war” to being “thrown into the swirl of great power politics like a piece of driftwood carried by a surging stream,” to the image of a “skillfully steered row-boat” managing its direction in the torrent of events (our emphasis).1 In this patriotic narrative, Finland was involved in a sequence of three conflicts: the heroic Winter War (November 1939–March 1940) against the Soviet Union when Finland, sold by Germany in the Hitler–Stalin pact of 1939, abandoned by the Allies, and dragged into the war countered the superior Soviet forces, eventually making a peace treaty ceding considerable eastern border territory to the Soviet Union; the Continuation War (June 1941–September 1944), in which the Third Reich and Finland agreed on exclusively military cooperation against the joint Communist enemy; and the Lapland War (September 1944–April 1945), in which a nearly defeated Finland was pressured by the Soviet Union to expel the German army stationed there. The circumstances of these wars were, of course, much more complex than this totalizing, neatly aligned oscillation between the heroic victor and hapless victim allows. Indeed, finding the appropriate term for the collaborative relationship of the Continuation War was particularly difficult. Adolf Hitler announced that the German forces were fighting im Bunde, in league with their Finnish comrades, provoking an immediate, public, denial from the Finnish government, which first declared its neutrality and subsequently maintained it fought a parallel, “separate war” against the Soviets, alongside but not allied with its German “brothers-in-arms.” Yet the public declaration of a “separate war” was immediately compromised, notably by Finnish defense propaganda: when Finland entered into Operation Barbarossa, Finland was imagined as fighting to save the New Europe—not exclusively Finland—from the “Asian plague.”2 Given the paradox of fighting a “separate war” to install the racially privileged New Europe, it is difficult not to see an ideological convergence that goes well beyond a merely pragmatic, military relationship between the “brothers-in-arms.”

Redirecting attention away from the ideological interinvolvement of the Finnish–German relationship—a sensitive issue given the powerful Soviet propinquity during the Cold War—in order to forestall both potential Soviet penalties and also national trauma following the gradual disclosure of the Holocaust after 1945, a normative framing of the alliance has been widely accepted both among institutional scholars and (with their help, too) the larger Finnish public. After the Finnish–Soviet armistice of 1944, the Soviet Union wielded direct and indirect influence in Finland, both as the result of its central role in the Allied Control Commission set up in Helsinki to oversee the terms of the treaty, and after the war through official and unofficial channels. It is now generally accepted that scholars toward the political right and center avoided issues that might conceivably damage Finnish interests in the eyes of the Soviets; more critical or left-leaning scholarship was simply denied credibility, as was scholarship arising abroad, which tended to regard Finland’s alliance as a tactic of “calculated risk” rather than the pursuit of “separate” political aims.3 The consensual narrative is reinforced by those (the Finnish volunteers in the Waffen-SS or the Finnish Jews, for instance) who participated in the war and under various pressures did not subsequently counter the master narrative. Until very recently, in scholarship and in public discourse the term “co-belligerent” formulaically reiterated a Finnish sense that the Finnish–German alliance was for nationally defensive military purposes, and that Finland’s parliamentary democracy and liberal institutions were unsullied by the dictatorial model and transnational politics of National Socialism. Notwithstanding casting Finland as having been involved in a mainly pragmatic, “separate war,” the notion of separation sanitizes the complexities of the alliance, in part by insisting that Finland stood entirely apart from the Reich’s racial ideologies and their in/human consequences. This perspective on history dramatizes the interplay between structures of national identification (Finnishness) and the ways they appear to have channeled the interpretation of the historical record—incomplete as it is—toward a specific way of reading the “reality” of Jews in Finland during, before, and after the war.

To be sure, though an ally of the Third Reich, Finland did not enact racial laws on the model of its “brother-in-arms”; yet it cannot be said that Finland or the Finnish state was uniformly opposed to aligning the Finnish people with the “Nordic” (Aryan) racial discourse as a means of improving its standing with Nazi Germany and securing its Lebensraum, Living Space, in the prospective New Europe. From the outset, then, separation was an emphatically rhetorical screen: while the Third Reich and Finland combined forces against the shared Communist enemy, a pro-German political and cultural elite was involved in the production and dissemination of racializing discourse for Finnish and German audiences, Finnish government offices produced a potent body of propaganda approximating a racial affiliation between the Finns and their “Nordic” “brothers-in-arms,” Finnish art was sent to Germany to represent the soul of a “Nordic”-related people, the Finnish State Police cooperated closely with its German counterparts, Finnish volunteers served in the Waffen-SS—all subjects touched on by essays in Finland’s Holocaust. Particularly from the point of view of Finland’s imagination of and participation in the project of New Europe, it becomes increasingly difficult to reiterate the thematics of separation in order to stage “Finland” as unequivocally “protecting” Jewish populations.

“Finland’s Holocaust” is necessarily a complex ligature, still denied by the consensual narrative, in which Finland not only preserved democracy, but also “protected” its native Jewish community, which in the 1940s numbered about 2,000 persons. One basis for this argument lies in the fact that male Finnish Jews fought in the Finnish army, and as some of them expressed after the war, “We were granted an incomprehensible blessing by our being able to fight for our freedom and human dignity while our unarmed brethren of the same faith were destroyed in neighbouring Nordic countries and elsewhere in Europe.”4

Instead of setting the narrative of the Jewish soldier in the critical context of the Finnish–German alliance, nationalist history turns to this Jewish figure to underline the trope of separation in moral terms. As historian Hannu Rautkallio puts it, “considered as a whole, the role played in the war by the Jews of Finland did not necessarily differ from that of the rest of the Finnish population.” And yet, the Jews nonetheless occupy for Rautkallio a distinct moral sphere:

every Finnish soldier of the Jewish faith had to justify to his conscience, in one way or another, his “comradeship-in-arms” with the Germans, no matter how theoretical its basis. As Jews, they had a better grasp than the other Finns of the historical connections of Germany’s racial policies. Their own ethnic background made them aware of how the flame of anti-Semitism can be fuelled by the slightest irritants.5

Rautkallio here effectively assigns responsibility for the morally compromising alliance: for the Finns, the moral dilemma of the “comradeship-in-arms” is characteristically “theoretical,” while the moral consequences of the alliance are charged to the Jews. The war had broken the figurative ghetto, as Finland needed the services of all its male citizens. Nonetheless, Rautkallio returns the Jewish soldiers to a kind of moral ghetto, and scapegoats them as well: given their alleged “better grasp than the other Finns of the historical connections of Germany’s racial politics,” the Jews bear any moral burden that might arise from the “comradeship-in-arms.” Including the Jews in Finland’s armed forces appears to mark Finland’s ideological separation from the policies of the Third Reich; yet in assigning the primary moral dilemma of fighting alongside the forces responsible for the Holocaust to the Jewish soldiers, Rautkallio effectively scapegoats them, using them to cleanse “Finnish” national identity of the implications of its compromising alliance.6

In June 2008, The Woodrow Wilson Center’s History and Public Policy Program hosted an international conference in Washington, DC, “Escape From the Holocaust? The Fate of Jews in Finland and other Scandinavian Countries,” featuring Rautkallio as principal organizer; Rautkallio also provided a short monograph, The Jews in Finland: Spared from the Holocaust, as a “guide to the subject matter.”7 Perhaps not surprisingly in this regard, the conference presented “the findings of recent studies of the exceptional status of Finnish Jews,” in the laudatory context of “the rescue of Jews from the Holocaust in several European countries.”8 Reiterating his sense that “The Finnish Jews were, at the same time, both spared from the Holocaust and participants in Hitler’s war against the Soviet Union,” Rautkallio underlines the implied purpose of the conference: “the systematic destruction of Jews was the central objective of Hitler’s eastern campaign. The credit for their not meeting this fate [in Finland] goes to the Finns.”9 Rautkallio’s remarks dramatize the extent to which the paradigm of separation is used to obscure possible antisemitism in Finnish society, and any possible “Finnish” connection to the Holocaust as well.

While Finnish postwar scholarship worked to install respectable (that is morally virtuous) notions of Finnish national identity and self-esteem, it exiled the subject of wartime antisemitism from the image of Finland. In one sense, boldly displacing antisemitism from the scholarly enterprise can be seen to undermine the development of a critical sensitivity toward the desensitizing attitudes and practices active within Finnish public discourse. Exiling antisemitism seems to resonate with the contemporary separation of Finland from the Holocaust as a European project. As Dan Stone pointedly demonstrates, although directed by National Socialist ideologies and practices, the Holocaust encompasses the “indigenous persecution that burst out under Nazi protection.”

Nazism burst the bounds of German ultra-nationalism and sought . . . to create a pan-European racial community, with the Germans and their racially valuable allies at the top and Slavs at the bottom, reduced to slaves. In this vision of a Nazi empire, Jews had no place at all. The Holocaust, then, was a European project, and the belated recognition of this fact helps to explain why at the turn of the twenty-first century European states finally began to acknowledge that it has something to do with them.10

The slow acknowledgment of a possible national implication in the Holocaust in Finland arises in part from the institutionalized uses of “history.”

Finland’s Holocaust?

Standing at the intersection of several competing models of Finland’s relation to the European project of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- 1 Introduction: Contesting the Silences of History

- 2 Stories of National and Transnational Memory: Renegotiating the Finnish Conception of Moral Witness and National Victimhood

- 3 Modes of Displacement: Ignoring, Understating, and Denying Antisemitism in Finnish Historiography

- 4 “I Devote Myself to the Fatherland”: Finnish Folklore, Patriotic Nationalism, and Racial Ideology

- 5 Towards New Europe: Arvi Kivimaa, Kultur, and the Fictions of Humanism

- 6 Discrimination against Jewish Athletes in Finland: An Unwritten Chapter

- 7 Elina Sana’s Luovutetut and the Politics of History

- 8 Negotiating a Dark Past in the Swedish-language Press in Finland and Sweden

- 9 Beyond “Those Eight”: Deportations of Jews from Finland 1941–1942

- 10 “Soldaten wie andere auch”: Finnish Waffen-SS Volunteers and Finland’s Historical Imagination

- Bibliography

- Index