eBook - ePub

Conquering Global Markets

Secrets from the World's Most Successful Multinationals

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Conquering Global Markets offers assessments of the issues, statistics, cases, and best practices of mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures and alliances throughout the world. Using information gleaned interviews with CEOs, the book provides insights into making global M&As successful.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conquering Global Markets by N. Hubbard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Economics of Globalization

Introduction

There has been a seismic shift in the global business landscape—those companies who clung to previously successful business models are frantically trying to reinvent themselves or dying. One only has to look at the demise of Eastman Kodak and Circuit City to see that the old business models no longer apply. A phrase being bantered about is the “global hyper-competitive marketplace” (Harvey, Kiessling, and Novicevic, 2003) in which the global landscape is a combination of rapidly changing variables, technology, uncertainty, and quickly appearing competitive threats (Ilinitch, Soderstrom, and Thomas, 1998). The world is increasingly diverse, complicated, and moving quickly. Everyone understands that the nature of competitive advantage is changing but no one is sure what will be required in ten years. Most understand what is needed: flexibility, adaptability, innovation, and the ability to replicate this across a number of markets. It is the ability to manage innate tensions from thinking globally but acting locally, not once but in 190 different locations. Some organizations are able to do this, others have failed, and still others choose not to even try.

Underlying this technology-enabled speed and diversity is a march toward globalization where companies see the world as one marketplace. It is a marketplace with geographic differentiation, but one marketplace nonetheless. This book analyzes that progression toward globalization and how these organizations have made the journey outlining their successes and hindsights.

As seen in the Introduction, globalization differs from internationalization although they are highly related. Internationalization is the process where an organization operates in more than one country. Globalization is much more than that. It is increasing the world’s social and cultural interconnectedness in terms of political interdependence and through economic means of financial and market integrations (Orozco, 2002; Nanda, 2009). It requires “a shift in traditional/historic patterns of investment, production, distribution and trade, requiring the development of inter-organizational relationships (i.e. strategic alliances) by organizations in order to meet, efficiently and effectively, the changes in demand for goods and services” (Harvey, Kiessling, and Novicevic, 2003, p. 223). Thus, in order to be global, it is nearly impossible to do it alone, as the vast majority of enterprises simply don’t have the resources throughout the world to create and support a truly global organization. These resources can include technology, communication systems, management talent with local market knowledge, or financial resources to fund the expansion. Instead cooperation with other organizations is almost always required. But the end result is worth the effort, as the move to a greater international investment has been found to lead to better firm performance (Hitt, Hoskisson, and Ireland, 1994) and higher returns (Agmon and Lessard, 1977). This finding is not universal because a small but significant group of researchers found that firm performance may actually go down due to the increased organizational complexities and potential losses related to operating in new and unfamiliar markets (Hitt, Hoskisson, and Kim, 1997). In either case, as will be seen in Chapter 3, the investor markets reward those companies seen as being international with higher ratings.

Patterns of globalization

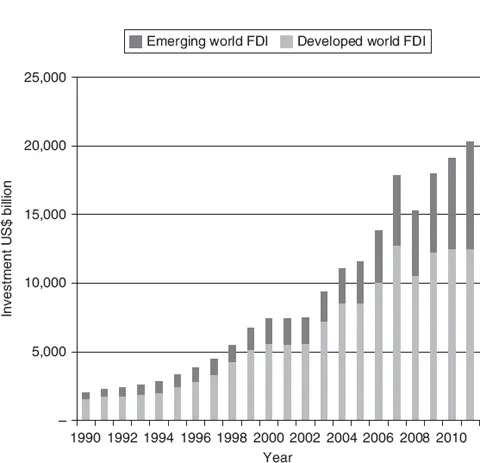

The patterns of globalization have changed quite dramatically over the past 20 years as the world has seen a meteoric rise in the scale and complexities of globalization. Organizations are increasingly investing in overseas economies as measured by their foreign direct investment (FDI). FDI measures the influx of capital investment from a home country’s organization into another and can take many forms such as acquisition, joint ventures, and greenfield sites, which are discussed in the following chapters. As seen in Graph 1.1, the levels of FDI has risen almost tenfold in real terms during the past 20 years to a 2011 high of over $20 trillion, the highest in history (UNCTAD, 2012).

Not only is cross-border investing reaching all-time highs but the composition of investment is changing considerably. Previously investment into the developing world accounted for less than one-quarter of all cross-border investment; in 2011 it accounted for over one-third, signaling an increasing attractiveness of the developing world as both a manufacturing hub and final destination for products (ibid.). As seen from those participating in the study, their organizations’ main objectives in FDI into the developing world was not seeking a source of cheap manufacturing but attempting to reach the rapidly sophisticating consumer markets of those countries.

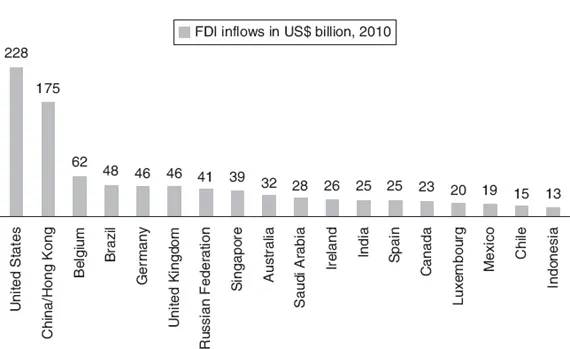

Where investment is flowing is also pertinent. Statistics shown in Graph 1.2 demonstrate the impact of FDI into the developing world with China overtaking the bulk of the developed world, becoming the second leading recipient of FDI just behind the United States (ibid.). Interestingly, in 2010, Brazil surpassed the United Kingdom and Germany in terms of a larger inflow of investment while the Russian Federation and Singapore surpassed France. India remains surprisingly low both in terms of inward flow (on par with Spain) and outward flow.

Graph 1.1 Levels of foreign direct investment into both the developed and emerging world, 1990–2011

Source: UNCTAD (2012).

Graph 1.2 The top 18 destinations for inflows of foreign direct investment, 2010

Source: UNCTAD (2010).

This investment trend seems set to continue. An UNCTAD survey asked TNC respondents to list their top priorities for inward investment during 2011–2013. Their answers in order of the number of times the country was mentioned are China, the United States, India, Brazil, the Russian Federation, Poland, Indonesia, Australia, Germany, Mexico, Vietnam, Thailand, United Kingdom, Singapore, Taiwan, Peru, the Czech Republic, Chile, Columbia, France, and Malaysia (UNCTAD, 2011). Of the 21 countries, only five are considered highly industrialized with the other 16 being either transition or developing economies. This survey’s participants concur that they are expecting their organizations to replicate this trend in the near future as 80 percent of participants indicated that the bulk of their investment in the next five years would be geared to the developing world. They cite the relative economic slow down in Europe and North America compared to the high growth rates in the developing world as being the main driver.

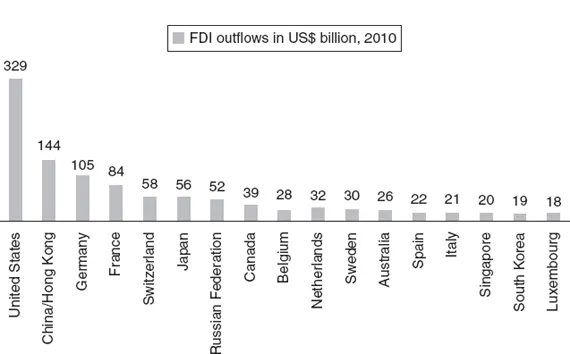

In the past, developed world organizations were leaders in cross-border investment into lower-cost centers; this pattern has now changed with emerging countries now seeking FDI in other parts of the world. For instance, as seen in Graph 1.3, China, when combined with Hong Kong, is by far and away the second leading source of FDI outflows again only behind the United States (ibid.). They are the biggest investors in Africa than any other country (UNCTAD, 2010). Similarly, the Russian Federation had the seventh largest outward FDI with emphasis being placed on resource-rich investments throughout the world (UNCTAD, 2011). And of the largest 16 investors internationally, one-quarter are now developing nation companies, including Singapore and South Korea. As will be explored more in the next chapter, globalization is now different than it was even 20 years ago.

Graph 1.3 Outflows of foreign direct investment from country of origin

Source: UNCTAD (2010).

Method of global expansion: Modes of entry overview

Once internationalization is the chosen path, there is a spectrum of how an organization wants to invest. There are several ways an organization can enter a market and they form the backbone of this book. In order to discuss them later in the book, it is worth providing a broad outline of what they entail.

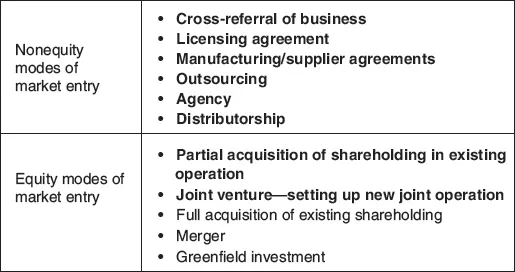

The least consumptive of resources and time is a nonequity mode of investment while at the other end of the spectrum is an equity mode of investment. In an equity mode of investment, the internationalizer is investing resources into a venture that can be done through a variety of means, including taking a shareholding in a company via a joint venture, merger or acquisition, or through a greenfield investment (see Diagram 1.1). These are discussed in much greater detail in Chapters 6, 7, and 8.

In some cases, the internationalizing business chooses to enter the market through a nonequity mode of investment—they enter into a relationship with another firm to facilitate their business in that region. Nonequity modes of investment are usually either designed to grow sales or reduce costs. Examples of top-line methods include using an agency to which one exports product for distribution or licensing technology, product, or a brand. Licensing agreements can provide market entry to those assigning a brand to another organization for use in a specific geography usually with the stipulation of quality assurance and adherence to the licensee’s marketing and overall strategy. Outsourcing is often used to reduce costs and can include the transferal of nonkey business operations to a third party whose expertise is the delivery of those operations. Potential areas of outsourcing include product manufacturing or assembly, logistics, back-office support, and customer services. These are discussed more in Chapter 5.

The phrase strategic alliance is often misused and misunderstood. Technically all forms of cooperation, whether it is through an equity position or nonequity modes of investment, are considered strategic alliances. All nonequity modes of investment are considered strategic alliances as are those equity modes of entry in which the internationalizer is sharing control with another company. Thus acquisitions, mergers, and greenfield investments are not considered strategic alliances. Global strategic alliances can be defined as “the relatively enduring interfirm cooperative arrangements, involving cross-border flows and linkages that utilize resources and/or governance structures from autonomous organizations headquartered in two or more countries, for the joint accomplishment of individual goals linked to the corporate mission of each sponsoring firm” (Kim and Parkhe, 2009, p. 364).

Diagram 1.1 Different types of nonequity and equity entry modes

Note: Bold indicates a strategic alliance.

Strategic alliances run the gamut from a loose, noncontractual collaboration between two or more organizations to one or more organizations taking equity in another organization; if a new entity is established in order to achieve those objectives, it becomes a joint venture (Yin and Shanley, 2009). For clarification, all joint ventures are strategic alliances while not all strategic alliances are joint ventures—only those where there is the investment of assets into a new entity are truly joint ventures. The assets don’t need to be tangible—local relationships and market knowledge are common assets used in the combined venture. The proclivity for internationalizing businesses to use strategic alliances has skyrocketed in the past two decades, as organizations have reacted to rapid changes in technology and deregulation and as no one enterprise, no matter how large, has all the resources they need in order to fully tackle all the world’s ever-changing markets (Shuman and Twombly, 2010).

Even with such a wide scope of definition, a successful strategic alliance brings with it a host of benefits, including the sharing or reduction of risk especially when entering new markets, the sharing of resources comprising technology and innovation, the ability to gain knowledge, as well as to obtain access to markets (Hitt et al., 2000). While the importance of strategic alliances has risen dramatically over the past 20 years, success rates have not, as they continue to demonstrate a high failure rate. A high level of dissatisfaction with actual outcomes relative to expectations has been reported and many are not successful. Although it is difficult to identify precise failure rates, it is estimated that roughly half of strategic alliances fail to meet participants’ expectations, are generally considered unstable, and as a consequence lead to high dissolution rates (Inkpen and Beamish, 1997; Hennart, Kim, and Zeng, 1998; Dyer, Kale, and Singh, 2004).

In terms of equity investments, the least consumptive of management time and resources is to take an equity shareholding in an existing local organization. An example of this is Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s 20 percent shareholding in Standard Bank of Africa (see Case 6.1 in Chapter 6) or Santander’s creation of a Pan-European bank that was created by the bank taking minority shareholdings of several regional European banks.

The last stage along the spectrum of investment from minority shareholding is when one buys the entire shareholding of an existing organization; this is considered an acquisition, discussed in depth in Chapter 7. Mergers differ from acquisitions in that in the former the management of two or more existing organizations decides to fully combine their operations into one, creating a new entity out of the existing structures. The previous organizations cease to exist and the shares of those organizations transfer into the new company.

Some organizations choose to enter a new geography through organic or greenfield investment eschewing any local partner involvement. This approach brings with it different complications and benefits that are discussed in Chapter 8.

The remainder of the book analyzes not only the various entry modes but also some unique characteristics of one group of globalizers, those from the emerging world. The growth they have accomplished in less than 30 years is truly remarkable and in doing so they bring with them some valuable lessons on how they achieved so much in such a short period of time. They are examined in Chapter 9. Finally, one specific market, China, is deserving of further attention. While other nations are developing rapidly, none have the size, scope, and economic clout of China. In addition, few have the complications of such a multifaceted market. It is examined in Chapter 10.

Conclusion

FDI has hit all-time record highs with not only investment flowing from the developed world into the emerging world but also in reverse. It will take one of the three forms...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Graphs, Diagrams, and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 The Economics of Globalization

- 2 Trends in Globalization

- 3 The Risks, Challenges, and Benefits of Being Global

- 4 How Do Companies Go Global: Choices and Issues between Entry Strategies

- 5 Nonequity Modes of Investment

- 6 Equity Investment Alliances and Joint Ventures

- 7 Mergers and Acquisitions

- 8 Greenfield Expansion

- 9 Emerging Market Companies as Globalizers

- 10 China as a Destination

- 11 The Next Decade and Beyond

- Bibliography

- Index