Painkillers were not always seen as dangerous drugs. Less than 20 years ago, these medications were largely regarded to be innocuous pharmaceuticals safely prescribed by the doctor. Since the early 2000s however, growing concern about the ability for painkillers to be ‘abused’ emerged alongside reports of spates of ‘illicit ’ pharmaceutical opiate consumption and related harm in Missouri (Harris et al. 2002), rural Kentucky (Tunnell 2005) and California, among other areas (Whelan et al. 2011). Since the early 2010s, concern about the harms of painkiller consumption has only escalated , with the non-medical use of pharmaceutical opiates being referred to as the ‘opiate crisis’ and as a ‘deadly drug epidemic’. What has made this starker to health practitioners is the fact that opiate overdose trends in the US have seen the largest increases in deaths among populations that have traditionally low rates of drug use ; this includes Caucasians, the middle-aged, those in the middle class and women (Rudd et al. 2016; Bohnert et al. 2011). The US context has seen increases in emergency room presentations related to opiate overdose (Yokell et al. 2014) and opiate dependence (Carise et al. 2007). Research also indicates that many of the country’s youngest generation of heroin users were first introduced to opiates through pharmaceuticals (Carlson et al. 2016; McCabe et al. 2007). Comparable patterns of harm have also emerged in epidemiological data from other parts of the world (Fischer et al. 2010).

The tragic circumstances that surround the harm being caused by opiate consumption in the US have also made its way into the popular imagination, with use of colloquial terms like ‘hillbilly heroin ’, ‘rich man’s heroin ’ or simply ‘killer’, reimagining medications such as OxyContin ® in the image of the urban ‘junkie’ that has haunted North American drug research for decades (Acker 2002). It has also inspired a succession of documentary films (Coker and Mackson 2017; Carney 2010) and autobiographical books (Lyon 2009; Stein 2009) devoted to telling the story of ‘normal’ people who use this ‘dangerous drug ’ and have become ‘addicts’. Pop culture accounts of opiate use and abuse have focused in particular on the way the recent painkiller crisis has changed the image of what an ‘addict’ is, often noting with surprise that ‘anyone can become addicted to painkillers’.

While many have declared opiate -related harm in the US an ‘epidemic’ (Conrad et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2015), public health data do not support the notion that the same conditions of harm have emerged in Australia . While Australia has seen significant increases in the prescription of pharmaceutical opiates (Blanch et al. 2014), opiate overdose deaths remained relatively low for some time (Roxburgh et al. 2011). Data from a variety of national monitoring programs also indicate that pharmaceutical opiate -related overdose deaths remain relatively low in Australia when compared to heroin (Roxburgh et al. 2011). Moreover, Australian research suggests that non-medical pharmaceutical opiate users tend to be people with an established history of injection drug use prior to first injecting pharmaceuticals (Nielsen et al. 2015; Degenhardt et al. 2006). Yet rates of heroin use in Australia have remained low (Coghlan et al. 2015), meaning that there is little evidence to suggest that pharmaceutical opiate use is seeding heroin use in the way that it has found to be in the US. However, since 2008 there has been a noticeable increase in overdose deaths related to pharmaceutical opiates, largely driven by increases in Fentanyl overdoses (Roxburgh et al. 2017).

Differences between the Australian and US context are illustrative of the fact that many questions remain unanswered by the public health information available about death and dependence . While epidemiology tells us that pharmaceutical opiate consumption represents a serious public health crisis in the US and an emerging problem in Australia , it cannot tell us why: What are the differences in the profiles of harm between the US and Australian contexts? Why do people use these medications in the first place? Answering these questions requires a different approach than traditional public health ’s inclination to record rates of morbidity and mortality can provide: it requires paying attention to the history of drug policy and research ; it requires an awareness of the structures that shape the society in which painkillers are consumed; and it requires a genuine engagement with the stories of people who actually use these medications.

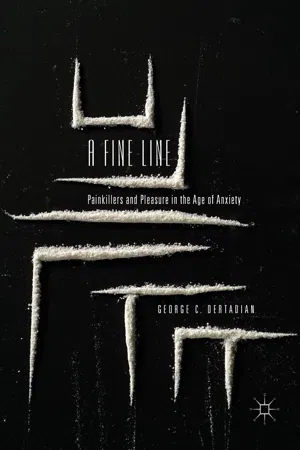

This chapter begins the task of this book by outlining the conceptual tools needed to analyze non-medical consumption of pain medications beyond the headlines about addiction and overdose . These tools will be used to articulate how the use of painkillers illustrates a fine line between medical and illegal use, pain relief and pleasurable consumption . This chapter will thus set out the theoretical background on which the book is based and the social conditions on which it comments. It will explore the social construction of the term ‘painkiller ’, provide a summary of relevant theory related to the analysis of medicine , drug use and consumption in late-modern societies, as well as articulate the way pleasure will be dealt with throughout the book and how the research was conducted.

What Is a Painkiller?

In simple terms, ‘painkiller ’ refers to a variable range of pharmaceuticals that are prescribed or used for the relief of pain . However, it is important to recognize that the categorization of a drug as a painkiller is highly context dependent , since it often includes controlled substances that are illicit unless prescribed. This necessarily positions medical practitioners and authorities as the crucial mediating agency in access to pain relief. The construction of a drug as a painkiller is therefore a social and legal process that is frequently elided in medical and scientific accounts.

The medical literature describes painkillers as a group of drugs that act on the peripheral and central nervous systems to achieve analgesia—relief from pain . This drug type is also commonly referred to as analgesic medication . Most analgesic medications are at least partial synthetic formulations derived but not directly extracted from the opium poppy. Analgesic medications available in Australia include paracetamol, ibuprofen and, the most popular, opioids (or opiates). Morphine is the major psychoactive chemical in opiate -based substances and is found in both its prescription (oxycodone, hydromorphone...