- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Seventy-five years after the Battle of Britain, the Few's role in preventing invasion continues to enjoy a revered place in popular memory. The Air Ministry were central to the Battle's valorisation. This book explores both this, and also the now forgotten 1940 Battle of the Barges mounted by RAF bombers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of Britain, 1945-1965 by Garry Campion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Air War, Media War

1

Seelöwe und Bomben Auf Engeland: The German Perspective, 1940

Hitler’s unexpected strategic dilemma

By 22 June 1940 Hitler’s armies had conquered Poland, invaded Norway and Denmark, defeated France and the Low Countries, and had forced the BEF out of France. What had threatened to deteriorate into a protracted and bitter conflict in the west had in fact been concluded so quickly that Hitler and the OKW had given little thought to what might come next. The only factor that was clear at this time was Hitler’s obsession with invading the Soviet Union, his views first aired in Mein Kampf.1 On 2 June during a visit to Army Group A HQ and even before France’s defeat, Hitler had told Field Marshal von Rundstedt of his interest in attacking Russia now that Britain might be ready for peace – Britain was at this point engaged in the Dunkirk evacuation. Thus, very soon after France’s defeat Hitler was torn between conflicting strategic aims: whilst he wished to reach a rapid settlement with Britain so that she no longer posed a threat or, more precisely, at that time remained an irritation on his western frontier, he realised equally that the Soviet Union was now within perhaps easy reach. Based on recent Wehrmacht success against a seemingly all-powerful France supported by Britain, an invasion of the Soviet Union was on this basis likely to succeed.

Fresh in Hitler’s mind would be several facts: a small Finnish army had revealed Red Army weaknesses during an attempted invasion in November 1939; Stalin had ruthlessly purged his officer corps during 1937–8; and German intelligence assessments were generally very dismissive of Soviet military capability.2 Hitler was also deeply suspicious of Stalin’s intentions, becoming increasingly convinced that he would attack Germany at the first opportunity, hence the Fuehrer’s preoccupation with this perceived threat.3 The prospects of an Anglo-Russian rapprochement were also of some concern were Britain to remain in the war. The chronology in Appendix 1 confirms that only days after France’s surrender the Wehrmacht was beginning, if only in outline, to contemplate an attack in the east, these plans steadily maturing in tandem with the air assaults against Britain as the summer and autumn progressed.

On the ‘English question’, in late June she hardly looked a threat of any consequence: Norway had been an embarrassment even when allowing for Royal Navy success against the Kriegsmarine; despite dogged fighting by the BEF it had been quickly routed and evacuated via Dunkirk, and was now without much of its equipment;4 the RAF’s fighter force (AASF) had fought bravely against the Luftwaffe but its Hurricanes had not given a clear impression of technical parity with the Me109 fighter;5 and finally, Britain was suddenly isolated and vulnerable to sea blockade, American aid not a material factor in July 1940.6 In short, Britain posed no immediate or obvious future threat and was easily contained in the nearer term. Hitler could therefore afford simply to do nothing given the above and during the four weeks following the Franco-German Armistice on 22 June until his peace offer to Britain on 19 July, he saw no pressing need to consider a snap invasion of Britain, even had he the wherewithal to do so.

A rapidly improvised invasion suggests of course that Hitler’s forces had the materiel and technical capability to invade Britain in late June or early July, but any close analysis of the realities soon dispels this notion.7 In fact, the French campaign had taken its toll of the German army and air force. The Wehrmacht had suffered quite high casualties, was exhausted after such a significant effort, and had many vehicle serviceability problems, whilst the Luftwaffe had suffered many aircrew and aircraft losses, and required time to replenish. There was also the small matter of occupying and making good former French air force airfields, and the practical realities of building new ones. Invading Britain at this point was therefore wholly unrealistic despite a weakened British army.

Similarly, as Admiral Raeder, the head of the Kriegsmarine well knew, the Royal Navy remained unbowed and would have played havoc with a hastily-improvised armada.8 Likewise, Milch’s fanciful argument to Goering that airborne forces using gliders and parachutes should be quickly deployed to capture key airfields so as to bring in reinforcements, and then force a surrender, was a highly optimistic assessment of German capabilities9 – German parachute losses over Crete showed the risks.10 Given the lack of military readiness on the one hand, and no clear strategy on the other, it is therefore unsurprising that little of note happened for several weeks as the Wehrmacht celebrated its victory. A Britain very much at bay was simply left to ponder an uncertain future and worry about how best to repel an expected Nazi onslaught.11 Viewed with hindsight it is all too obvious that allowing Britain to remain in the war was the decisive factor in Germany’s eventual defeat, but in June 1940 it hardly appeared thus as Hitler surveyed a large empire running in the west from Norway down to the Spanish border, and to the east, the long border with the Soviet Union (Plate 5).

Operation Sea Lion

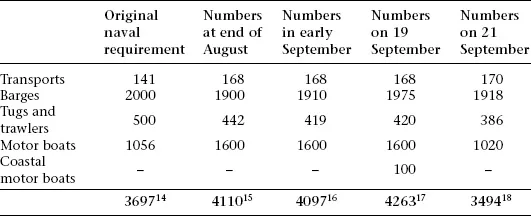

Hitler’s invasion never launched, his ambitions for Seelöwe, or Operation Sea Lion, have been the focus of considerable debate since the Second World War, not least because planning for it had not been undertaken in a serious manner before the war began.12 In essence, after Dunkirk and Britain’s determination to continue the fight Hitler set his OKH the aim of landing an invasion force along various points of south-east England, and rapidly thereafter making progress towards London and the English midlands. A large German force of over 260,400 men, supported by 34,200 vehicles, tanks and artillery, 52 light flak batteries, 61,983 horses, and other necessities, was to be ferried across the English Channel in three waves.13 It fell to the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, to mastermind this process, but not unreasonably they were very concerned about the RAF’s strength where air superiority over the landing beaches was deemed a vital prerequisite, and also the overwhelming might of the Royal Navy. Table 1.1 confirms the broad numbers of vessels requisitioned and assembled for Sea Lion but also demonstrates the difficulty in assessing final numbers available for use by the German Navy as losses from British air attacks occurred between July and October (see Table 3.2, p. 71).

Table 1.1 Vessels required, requisitioned and assembled by the German Navy for Sea Lion (compiled by Garry Campion from several book details)

Sea Lion’s broad chronology has been well documented (see Appendix 1) even if Hitler’s reasoning has at times been harder to fathom. The sixteenth of July 1940 saw him issue War Directive No. 16, setting out a series of conditions that had to be met in order for an attempted invasion, air superiority deemed vital in order to offset the Royal Navy’s primacy.19 On 1 August 1940 he confirmed in War Directive No. 17 that the destruction of the RAF was to be carried out, Sea Lion to be staged thereafter.20 The developing air attacks were in part the Luftwaffe’s attempt to soften up and progressively destroy the RAF so that it would be unable to mount any effective resistance over the Channel crossing and invasion beaches, and critically, would allow the Luftwaffe a free hand against the Royal Navy. The German Naval Staff had, though, recorded doubts on 1 September 1940, even before the main RAF offensive had been launched on 7–8 September:

[T]he enemy’s continuous fighting defence off the coast, his concentration of bombers on Seelöwe embarkation ports […] indicate that he is now expecting an immediate landing […] The English bombers […] are still at full operational strength, and it must be confirmed that the activity of the British forces has been [quite] successful.21

Fighter Command proving less easy to destroy than had been expected, and facing mounting attacks by its bombers against invasion preparations, on 14 September 1940 Raeder noted that these factors made the invasion risks very great.22 Although initially resisting his appeal to abandon Sea Lion, and demanding a final effort against the RAF on 15 September 1940,23 it was clear after heavy Luftwaffe losses that air superiority had not been achieved, Hitler postponing the invasion on 17 September 1940.24 On 19 September an order was issued in response to heavy RAF attacks, the invasion fleet dispersal beginning on 20 September.25 With raids continuing against invasion ports and shipping, Sea Lion preparations were officially wound down from 12 October 1940, and remaining vessels continued to be dispersed.26 Further confirmation of the receding invasion threat came on 21 November 1940 when Hitler’s War Directive No. 18 noted that Sea Lion might have to wait until early 1941 before being re-launched; it was striking, though, by 5 December 1940 that it had been utterly abandoned, if not officially confirmed in a directive.27 These are the basic facts as accepted in most histories, but much more hotly debated are the precise reasons for its abandonment: these aspects are considered below, and also in Chapters 3 and 8.

German propaganda during the Battle of Britain

Setting the scene: mid-June 1940

In tandem with planning and preparations for an attempted invasion was the parallel propaganda war, this deemed an essential aspect of Germany’s war-making strategy. It had clearly worked wonders in other theatres and there was every reason to believe that in conjunction with military action, it would do so again. In order to understand the development and progress of Germany’s propaganda efforts during the latter part of 1940 it is necessary to return to France’s recent surrender.

Whilst ordinary Germans – to Hitler’s dismay – had generally been very lukewarm and anxious about the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, it is undeniable that rapid campaign success had resulted in a dramatic surge of popular support for him by July 1940.28 Earlier anxieties shaped by the First World War and its aftermath were quickly forgotten as one country after another fell to German military might, her armed forces suffering relatively modest casualties given the large territories gained. It also mattered that there was little wartime impact on domestic life in Germany, pre-war household goods still available in quantity.29 To most Germans the war seemed very distant, Britain, seemingly on its knees, its BEF having been unceremoniously knocked out of mainland Europe and licking its wounds across the English Channel.30 With no obvious way for Britain to sustain the war ordinary Germans were understandably both thrilled and reassured by Hitler’s run of victories. Even where there may have been ideological resistance previously it was now prudent for German citizens to fully embrace the realities of Nazi dominance, which, viewed from the perspective of June 1940, appeared to be a now permanent and immutable aspect of their daily lives.31 Within this context, manipulating German domestic public opinion was, therefore, made easier in mid-1940 given the prospect of a rapid end to the war and a return to peacetime conditions; Hitler’s plans to invade Russia as yet embryonic and wholly unsuspected by many Germans, not least because there was no obvious rationale for it, even to his general staff.

However, as with British propagandists, Germany had not planned to be heavily engaged in either an actual conflict or propaganda war with Britain as a sole adversary at such an early part of the war, and in tandem with Hitler’s wider strategic plans, there was no clear propaganda strategy per se to exploit recent German successes.32 These obstacles aside, Nazi propagandists nevertheless had four constituencies at whom they had to project pro-regime propaganda: German civilians and the military; neutrals including America;33 occupied countries under the yoke of Nazism;34 and finally, Britain and its Empire.35 British propagandists were e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Plates

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Chronology

- Introduction

- Part I Air War, Media War

- Part II Valorising and Thanksgiving

- Part III Commemoration and Popular Memory

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Chronology of German-focused Events, 1939–1941

- Appendix 2 Nazi Battle of Britain-related Propaganda

- Appendix 3 Radio and Audio Coverage of the Battle of Britain, 1940–1965

- Appendix 4 Printed Coverage of the Battle of Britain, 1940–1965

- Appendix 5 Newsreel, Film and TV Coverage of the Battle of Britain, 1940–1965

- Appendix 6 War Artists

- Appendix 7 Books and Printed Literature, 1940–1965

- Appendix 8 Chronology of Political and World Events, 1945–1965

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index