eBook - ePub

Refugee Politics in the Middle East and North Africa

Human Rights, Safety, and Identity

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ahsan Ullah provides an insightful analysis of migration and displacement in the Middle East and North Africa. He examines the intricate relationship of these phenomena with human rights, safety concerns and issues of identity crisis and identity formation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Refugee Politics in the Middle East and North Africa by A. Ullah in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rights, Safety, and Identity: The Context of Forced Mobility in the MENA

Every human being is born with certain fundamental rights. These rights entitle everyone to a degree of safety for life and existence. Identity is one factor that knits together the fabric of both rights and safety. However, due to differences in geographical and economic landscape, differential opportunities, and political differences these three critical issues – rights, safety, and identity (RSI) – bring differential results to the lives of migrant and refugee populations. Metaphorically, we say that the world has significantly transformed in the second half of 20th century due to the ongoing process of globalization. From a political perspective, some parts of the world are globally marginalized, while others are semiglobalized or advanced. Adaptation of market liberalization and competitiveness are perceived as significant constituent components of globalization (Beblawi and Luciani 1987; Larsson 2001). The notion of globalization may get distorted depending on the premise and location its definition is based on. Some economies perform well in the face of economic interdependence to compete with globalization; some grow faster than globalization itself. This creates an unequal race in the world. This has implications for rights, safety, and identity for refugees and non-refugees alike. Anthony Giddens has defined globalization as “the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local activities are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa” (1990, 64). Albrow adds that people are increasingly tied into a single world society (1990). This remarkable change has initiated new phenomena and also raised fresh concerns.

Theoretically, it is both fascinating as well as horrifying to think that globalization itself is driving us apart from each other. In an unequal world, not everyone can engage in the race toward globalization. Global migratory movements are clearly one of the indicators of globalization: “Since the 1960s, a number of major developments in global migration patterns have placed the phenomenon at the heart of international politics” (Stivachtis 2008, 10). These developments include an unparalleled scale and heterogeneity of population mobility, which have reshaped culturally homogeneous localities into unprecedentedly diverse mosaics, mixing not only people, but also norms, values, approaches, habits, and practices. With the rapid changes of social composition, new challenges have emerged, undermining the nation-state, and its relationship with citizens that leads to the feeling of identity and security. The rise of “super-diversity” (Vertovec 2007) brought also the rise of discrimination, xenophobic violence, intolerance, and identity politics, namely, competition and conflict, controversially diagnosed by Samuel Huntington as “a clash of civilizations” (Huntington 1993). Simultaneously, the world has witnessed the “rights revolution” (Sunstein 1990), with an emerging discourse on human rights encompassing the whole of mankind without any exceptions. Human rights violations or deficient mechanisms of human rights protection result in enhanced insecurity for refugee populations.

This chapter sets out the main argument, objectives, and conceptual issues upon which the manuscript is built and outlines a theoretical framework from which the following chapters proceed. The conditions that contribute to the ongoing refugee situation and the growing claims of human rights violations affecting the lives of refugees in the region are also analyzed. The chapter, which is broadly divided into two sections, describes refugee contexts of selected countries from the region. The first section presents a theoretical framework outlining the main theories of identity, safety, and human rights that allows the reader to connect each chapter with the essence of the book. This section conceptualizes notions of identity, safety, and human rights within the refugee context. The second section includes the conceptualization aimed at addressing the vacuum in scholarship and is primarily organized around geographical and political settings. I identify these three powerful notions – rights, safety and identity – as critical areas where the lives of refugees are caught in a difficult predicament.

In analyzing the conditions that have generated huge numbers of refugees, it is necessary to understand the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) as an economically diverse region including both oil-rich and resource-scarce economies. Two primary factors influenced the region’s economic fortunes in the past decades: the price of oil and the legacy of economic policies, such as the policy on diversifying economy and the import substitution industrial policy. With approximately 32 percent of the 350 million people in MENA living on less than $2 a day, fighting poverty is part of their daily lives (World Bank 2012). Seemingly unresolved multilayered conflicts have also characterized the MENA region’s interstate relationships during recent decades. The Arab-Israeli conflict, inter-Palestinian power relationships, territorial claims and border issues, ethnic-based confrontations in various localities, and the ongoing Arab uprisings are among the best examples of such conflicts. These situations have certainly harmed potential economic relations and prospects for cooperation in the region. The stunning contrast in the region in terms of economic progress also is an intriguing addition to the discourse of the critical areas of rights, safety and identity.

The three systems in the region – the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Maghreb, and Mashreq – are distinctively characterized by differing geopolitical and economic landscapes. A significant portion of about 45 million refugees and asylum seekers globally originate from the MENA region. And, 55 percent of refugees come from five countries affected by war; Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Syria, and Sudan (Guardian 2012b). “By end 2012, 45.2 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence and human rights violations. Some 15.4 million people were refugees: 10.5 million under UNHCR’s mandate and 4.9 million Palestinian refugees registered by UNRWA. The global figure included 28.8 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and nearly one million asylum seekers. The 2012 level was the highest since 1994, when an estimated 47 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide” (UNHCR 2012f, 2). The UNHCR currently cares for 10.4 million refugees worldwide, while the UNRWA helps some 4.8 million registered Palestine refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the occupied Palestinian territory (United Nations 2013).

Political persecution, ethnic and religious conflicts, and poverty have contributed to the growing number of refugees. This population has emerged as one of the most vulnerable groups in the world. Their vulnerabilities essentially stem from three critical areas: failures in protecting human rights, providing safety, and creating identity. While various refugee regimes have been working in this critical area, there are widespread claims that the efforts are less effective than they appear. This book therefore advances with a number of noteworthy arguments, suggesting that these phenomena have been continuously evolving and that the refugee regime fails to sufficiently address the various issues of refugees. There are inherent lacunae within the protection agenda of the humanitarian organizations; hence, the expected yields have not appeared. These arguments have been substantiated by evidence from selected countries in the region. At present, refugees from any country are entitled to seek protection in one of the 147 countries that are party to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention). Refugee status is important for the rights it bestows under international law (Ben-Nun 2013). A refugee is entitled to reside, at least temporarily, in the host country and is protected by the principle of non-refoulement. Host states are obliged to offer civil and economic rights, and refugees enjoy access to social services and the protection of national laws.

The second section of this chapter includes the conceptualization of the research the manuscript is based on. Research on refugees is a complex undertaking, and there is no tested method for studying refugees. Research challenges are exacerbated by the need to conduct research in precarious conditions where refugees reside. In this way, this book addresses the vacuum in scholarship and prepares the ground for designing research based on geographical and political settings, and it proposes new alternatives for addressing these challenges posed by the context.

Forced mobility, geopolitics, and MENA

I have developed the concept of Rights, Safety, and Identity (RSI) as a critical area for a number of reasons. In the following sections, I illuminate why RSI became the center of the discourse on refugee movements. This book considers RSI and three areas of refugee studies: the drivers of forced migration, refugee rights and humanitarianism, and trafficking and policy responses. Studies and researches conducted in these areas have in the past grasped these issues largely in isolation. This book, on the other hand, proposes an interlocking approach. In doing so, it encompasses, for instance, a host of issues related to human mobility, such as voluntary and involuntary mobility, conflict and humanitarianism, human rights, and unaccompanied children. Indeed, RSI is involved at various levels of mobility. Livelihoods lead humans in certain directions, and at some point in history colonialism gave a different shape to human mobility around the globe. Such mobility was later driven by new economic considerations, where the global economy and global politics – over the last centuries – created competition over land, water, oil, dominance, and power. Migration has been taking place as a result. No geographical space around the world is spared enhanced migration. However, MENA hosts entirely different dynamics of human mobility in terms of preferences of destinations and motivations. Internal conflicts on different fronts in almost all the countries that were liberated and nearly liberated from colonial influence between the 1950s and 1960s suffer from common phenomena that continue to produce conflict and millions of stateless and displaced people. Highly political, refugee rights and safety in the region are in a volatile situation.

The current discourse about refugees and their RSI stems from this historical past. Yet, there are many current challenges to providing protection and lasting solutions for refugees in the MENA region. A few pressing questions remain: Who facilitates the creation of mass refugee flows and who should support and provide protection and assistance? Do neighboring countries within the region do their part to host and include refugees? How does political turmoil in host countries, such as Egypt and Syria, affect the availability of meaningful protection to refugees? Domestic upheavals within MENA states have significant impacts both within and beyond the region.

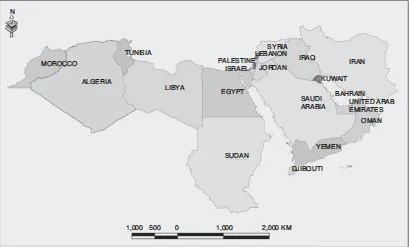

Confusion is rife in the understanding of geographical the location of MENA. Some say location of the MENA is a creation of the mind. Hazbun (2011) for example, articulated that the Middle East is a region of the globe defined from the point of view of the north Atlantic states and is devoid of geographic or cultural referents. There are arguments that there is no standardized list of countries that constitute the MENA region. Some geographers contend that the term typically includes the area from Morocco in northwest Africa to Iran in southwest Asia and down to Sudan in Africa. The Western public and news media often associate the Middle East with particular political, economic, and cultural characteristics. Among these associations is that the Middle East represents a territorial exception to globalization (Hazbun 2011; Adelson 1995). The Middle East and the North Africa are two separate regions. Still these regions are perceived and viewed as a single entity, united by a number of political, religious, and cultural commonalities despite significant economic disparity. The MENA region has 60 percent of the world’s oil reserves and 45 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves. About 5 percent of the world’s population lives there, but they have access to only 1 percent of the world’s supply of fresh water (Gärber 2007). The population of this region is also disproportionately distributed. About 40 percent of the total population live in Iran (75 million) and Egypt (84 million); in contrast a large number of small and very small states have populations of less than 5 million (including the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman) or of less than 1 million (including Qatar and Bahrain).

Map 1.1 Map of MENA regions

There is a long-standing debate and confusion regarding the particular countries constituting the MENA regions. For the purposes of this book’s discussion, I rely on the World Bank’s definition of the MENA region, which includes: Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen (World Bank 2013).

The countries in the region have heterogeneous political systems, including: monarchies (GCC states, Morocco, and Jordan), republics with secular, authoritarian presidential regimes (Egypt – changed recently after overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak, but again in July 2013 the elected president was deposed by the military – Syria, Tunisia, and Algeria), or Islamist (military) regimes (Sudan and Iran), dysfunctional democracies (Lebanon) (Brand 2006), occupied countries arguably moving toward democracy (Palestinian territories, Iraq), and democracies (Israel). What factors prompt this region to produce such a large number of refugees? This remains one of the most of significant questions in the refugee discourse. Some reasons could include: historical armed and unarmed and political conflicts over borders and resources, lack of freedom, and recent Arab uprisings. The high profile conflicts of international significance – the Middle East territorial conflict over Palestine, the Iraq conflicts of various forms and among sects, the hegemony conflict in the Persian Gulf, and the international conflict over Iran’s nuclear ambitions – as well as some low-profile conflicts with regional ramifications, such as the Darfur conflict in Sudan, the West Sahara conflict, and the Kurdish conflict have also led millions to leave their countries of origin (Gärber 2007).

The region has also failed to be fully integrated into trends of globalization. Perhaps, it is said, because of the low international trade (around 3.4 percent) and because intraregional trade is below 10 percent, except for the intraregional migration of labor. The region is divided into three economic subregions, often called systems: the Maghreb, the Mashreq, and the GCC. These systems are intended to coordinate political and economic cooperation. However, they are either suspended (e.g., the Arab Cooperation Council), frequently impeded and unable to act (e.g., the Arab League), or exist only on paper (e.g., Arab Maghreb Union). The GCC was originally founded as a security alliance against the Iranian threat in the 1980s. The main impetus for the creation of the GCC was political rather than economic. Nevertheless, the GCC has proven to be a relative success in terms of the economic integration it has reached since its establishment (Broude 2010, 289). In addition, the region suffers from the colonial legacy. For instance, the border drawn during colonial periods caused many border disputes in the present time. Colonial states tended to be authoritarian; today we see that almost all states – with a few exceptions, such as Lebanon – adopted a postcolonial development strategy based on state interventionism. There is an interesting as well as dangerous twist regarding military spending in the region. Gärber (2007, 5) offers very relevant examples of such a twist: if Saudi Arabia, for example, purchases arms as a deterrent against Iran, Israel feels threatened. When Israel purchases arms, Syria feels threatened. Syrian arms purchases provoke Turkey. Turkey’s arms purchases threaten Iran. Iran’s arms purchases provoke Saudi Arabia. This means the entire region is chained by mutual distrust, which creates a tense situation in the region. A number of peace processes, agreements, and accords (such as Oslo peace process, Geneva Accord, Camp David Agreement, Road Map Plan, Madrid Middle East Peace, and Casablanca Agreement) were signed in order to bring this region back to a peaceful region (see Chapter 2).

RSI: the framework for critical analysis

I will now elaborate on the theoretical framework of this book in order to demonstrate the complex and multidimensional linkages between the three concepts of pivotal importance: security, human rights, and identity in the context of migration and refugee studies. Primarily, I touch upon the conceptualization of these three terms separately and, subsequently, the analysis of their interrelations follows with the emphasis on the modern migratory context. This part is divided into three separate sections: identity – security, security – (human) rights, and identity – rights. This arbitrary division serves the purpose of clarity; however, all of the topics are closely related to each other (Hornsey 2007). Security and autonomy are inextricable concepts. It is impossible to conceive of security without autonomy and vice versa. Without according autonomy, we similarly cannot guarantee security. In order to provide security to a refugee, autonomy should be taken into account. However, limiting autonomy under the pretext of security provision is common in the refugee context.

Security constitutes an important part of identity development, which is largely dependent on how secure a person is in a particular society or an environment. In an insecure environment, an individual cannot develop as a normal human being. Freedom and autonomy play important roles in identity development and formation. However, here I emphasize “controlled freedom,” which is not necessarily free will and does not necessarily allow a person to do whatever he or she likes. Enjoying freedom should not go beyond social norms. Some may argue that responding to social norms...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Rights, Safety, and Identity: The Context of Forced Mobility in the MENA

- 2 MENA: Geopolitics of Conflicts and Refugees

- 3 Refugees in Camps: Anatomy of an Identity Crisis

- 4 Refugee Safety and Humanitarianism Discourse

- 5 Refugee Rights, Protection, and Existing Instruments

- 6 Arab Uprisings and New Dimensions of Refugee Crises

- 7 Discussions and Policy Implications

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index