eBook - ePub

Gender and Welfare States in East Asia

Confucianism or Gender Equality?

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Contributors address questions about gender equality in a Confucian context across a wide and varied social policy landscape, from Korea and Taiwan, where Confucian culture is deeply embedded, through China, with its transformations from Confucianism to communism and back, to the mixed cultural environments of Hong Kong and Japan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender and Welfare States in East Asia by Sirin Sung,Gillian Pascall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Gender and Welfare States in East Asia

Sirin Sung and Gillian Pascall

Introduction

This book aims to uncover gender assumptions of welfare states that are very different from Western ones, and to understand women’s experience of welfare states across a range of East Asian countries. Gender inequalities in East Asian social policies are clearly important for women across East Asia, and yet they have had too little attention in the literature comparing welfare states. The comparative literature has largely been concerned with Western Welfare states, whether in The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Esping-Andersen 1990), or in gender-based analysis of the male breadwinner model (Lewis 1992, 2001, 2006). Are the welfare systems of East Asian countries distinctive, with Confucian cultural assumptions hidden beneath the surface commitment to gender equality? While economies have been developing rapidly, are social policies becoming less traditional in their expectations of women? East Asian welfare regimes have been studied since the late 1980s, but research questioning their underpinning gender assumptions is new.

The book showcases new research in several East Asian countries, including Korea, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong and Japan, to develop an understanding of gender in welfare systems that have some common history and culture. It will bring together research on gender in welfare systems with a Confucian history. It will also ask about the extent to which Confucian values and practices of gender difference persist in the context of modern welfare states with gender equality legislation. How seriously are gender equality policies promoted by governments? What impact do gender equality policies have at the household level? How difficult is it for households to practise gender equality in these contexts? Are Confucian values more powerful and gender differences more extreme than comparable aspects of Western welfare systems? How do such conflicts play out in China and Hong Kong, countries with similar cultural backgrounds but contrasting political ones? Has the communist attack on Confucian gender inequalities created societies in which women and men are equally valued and have equal power in households? What assumptions now underpin social policies, and how are they experienced in practice? How is the welfare system in Hong Kong managed in the post-colonial period? Some (Chiu and Wong 2005: 97) argue that the new SAR government’s new vision for Hong Kong is an ‘amalgamation of Confucian values and free market economy’. How does this affect gender equality and policy issues in Hong Kong?

These chapters complement the broad brush debates in the introduction with detailed discussion of gender in the welfare systems of individual East Asian countries. The book discusses the combination of change and tradition in East Asian welfare states. Rapid economic development makes East Asian economies remarkable, as ‘tiger economies’, bringing a transformation of living conditions. These changes bring clear social benefits, with women’s life expectancy in Japan the highest among OECD (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development) countries, and Korean women’s life expectancy increasing at a faster pace than any other OECD country. Political changes bring gender equality legislation, which is important for improving women’s rights in employment and family law. There are signs of change in society – including gender – as well as in economy and polity. Detailed study of women’s experience in practice, particularly as mothers in marriage, and out of it, shows the persistence of some traditional family hierarchies which put younger mothers under unusual pressures, and which could not be described as gender equal. But there is room for optimism that women’s involvement in social movements and academic enquiry may be challenging Confucian gender hierarchies (Pascall and Sung 2007).

Social and economic change

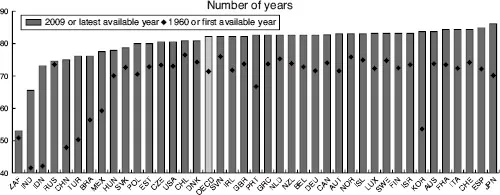

Rapid economic and social changes are a crucial backdrop for understanding East Asian welfare states and the changing legislative framework impacting on gender. Korea is one of the fastest growing economies in the OECD, sustaining rapid growth through the crisis years of 2007–2012 (OECD 2012a). Economic change brings clear benefits: life expectancies are among the highest in the world, with Japanese women expecting to live to 85+, while Korean women have higher life expectancy than UK women, despite per capita income of around two-third the UK figure (OECD 2011). According to the Population Database from the United Nations (2009), life expectancy in China is also rising sharply: by 2040 the average life expectancy will reach 78 years and more than 20 per cent of population will be over 65 (in Ye 2011). China is also facing demographic transition with rapid economic growth, from a ‘high fertility, high mortality phase to a phase of low fertility and low mortality’ (Ye 2011: 679). Figure 1.1 draws on OECD data to show the leading position of East Asian countries in life expectancy, with Japan and Korea above the Western social democracies:

Figure 1.1 Life expectancy at birth: women, 2009

Source: OECD Factbook 2011a.

Japan has nearly the lowest Infant Mortality Rate, even among the social democratic countries such as Iceland, Sweden, Norway and Finland, while Korea’s is again close to the United Kingdom’s, despite Korea’s lower per capita income (OECD 2006). Increasing life expectancy and low infant mortality are clear indications of women’s health (Pascall and Sung 2007).

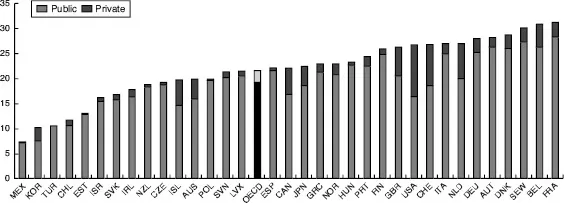

But public social expenditure in East Asian countries remains low. Korean public social expenditure, as a percentage of GDP, is among the lowest shown in Figure 1.2, in contrast with Scandinavian countries at the other end of the spectrum. Private spending fills some of the gap, but Korea’s social spending altogether is low, suggesting that families fill much more of the gap:

Figure 1.2 Public and private social expenditure, as a percentage of GDP, 2007

Source: OECD Factbook 2011a.

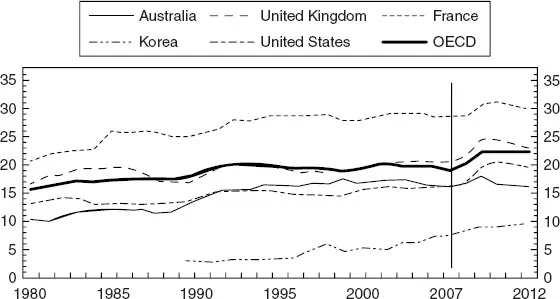

Japan’s public social expenditure is also below the OECD average. These data give rise to doubts about governments’ commitments to the social care activities which have tended to define women’s domestic lives and contain their public ones. Figures for public social spending over time (Figure 1.3) show Korea increasing from around 5 per cent in the 1990s towards 10 per cent projected for 2012, but remaining well below the OECD average, and even further below that of France, given here as a contrasting Western European example:

Figure 1.3 Public social spending, as percentage of GDP, for selected OECD countries, 1980–2012

Source: OECD 2012a Social Expenditure Database.

Policy changes, bringing gender equality legislation, are important. In Japan, the Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society in 1999 described a gender-equal society for the first time in Japan and required the state to promote gender participation and gender equality. The opening article of this law proposes ‘a “gender-free” society which does not reflect the stereotyped division of roles on the basis of gender but rather has as neutral an impact as possible on the selection of social activities by men and women as equal partners’ (Takao 2007: 153). Japan’s mandatory long-term care insurance was started in 2000, bringing entitlement to those aged 65 and above, to institutional and community-based care, according to need, bringing an ‘abrupt shift of gender policy’ (Takao 2007: 154) from earlier assumptions about the obligations of daughters-in-law. The government’s perceptions of a need to bring women into employment, while increasing the birth rate, are seen as crucial contributing factors to this change, while women activists have also played a vital role (Takao 2007). In Korea too, there have been important developments in gender equality legislation. Since 2001, the Ministry of Gender Equality has been the focus for state policy, operating through women’s bureaux and through legislation: the Gender Equality Employment Act, Framework Act on Women’s Development, and Employment Insurance Act (Won 2007). These are clearly significant symbolic moments in women’s action towards gender equality, but we need to ask about their significance in practice under Confucian conditions.

Culture and gender: East Asian culture in transition?

Confucianism has been identified as the main cultural heritage in East Asian countries by many Western and Eastern scholars. Some argue that Confucian traditions, such as diligence and hard work, a great emphasis on education, and dutifulness, helped East Asian countries to achieve rapid economic growth. However, others downplay economic growth in favour of the disadvantages imposed, particularly in relation to gender: ‘in traditional Confucian societies women were in a disadvantaged position’ (Palley and Gelb 1992: 3). The Confucian influence on women’s position in society can be best represented with the virtue of three obediences: ‘to the father, the husband and the son’ (Lee 2005). After marriage, women belong to families-in-law and become strangers to their natal families (Sung 2003).

These strong Confucian traditions on women are indeed changing, as a result of industrialization, changes in family structure, women’s increasing participation in the labour market and the recent development of gender equality policies. However, in East Asian countries, tradition and modernity co-exist: Western influence of gender equality ideals and traditional Confucian patriarchal family systems are intertwined within these societies. As Lee (2005: 166) argued in her research on women and the Korean family: ‘although the Korean family resembles the nuclear family in structure, in terms of the actual activities undertaken within it, the principles of the stem family and the extensive influence of the traditional conceptualization of the family have not diminished’. Married women are still more responsible for their family-in-law than their own families. In her research, women often felt duty and responsibility to their parents-in-law, although they were emotionally closer to their natal families. Women also often gave priority to their husbands’ families over their own, while men did not feel the same way about their wives’ families. This shows that the Confucian tradition still has a strong influence on women in Korean families. In Japan, though with weaker influence of Confucian traditional gender roles than Korea, women’s status was often considered as secondary in society and resulted in limited roles for women (Palley and Gelb 1992). In Taiwan, it still seems women’s primary roles as carers and domestic workers have not substantially changed, despite the increasing numbers of women entering the labour market as wage earners (Wu 2007). According to Lin and Yi (2011), the strong patriarchal cultural heritage in China and Taiwan influences intergenerational support to ageing parents. From the 2006 East Asian Social Survey, they found that traditional Chinese filial norms still prevail in intergenerational relations. For instance, it is expected that adult children – especially sons – will take the major responsibility for parental support, by co-residence and by providing financial resources. Wong’s study (1995) of Hong Kong found about 60 per cent of respondents agreed that children should take the primary responsibility for the financial needs of elderly parents (cited from Chan 2011). While women’s increasing participation in the labour market represents social and cultural change in East Asia, it is also important to note that traditional gender roles still prevail within the family and wider society. In this transitional period, East Asian women may encounter conflicts within their families and societies, as well as within themselves.

Family law: gender equality legislation

The family’s key role in society as a provider of social welfare is common to East Asian welfare systems. Welfare systems have been described as ‘productivist’, emphasizing economic objectives with strong education and health services to reproduce human resources (Holliday 2000, 2005), or Confucian, to emphasize the role of the family in welfare and of Confucian values in social harmony. Confucian values may be seen as a cover for welfare states pursuing economic growth at the expense of everything else: in particular, real Confucian values of social solidarity (Chan 2006). While welfare states everywhere have a place for family responsibility, East Asian ones draw on Confucian values to give families a very special responsibility for social welfare. A Confucian tradition of patri-lineal and patri-local families has influenced family living arrangements, with three-generation households, sons expected to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction: Gender and Welfare States in East Asia

- 2 Work–Family Balance Issues and Policies in Korea: Towards an Egalitarian Regime?

- 3 Rhetoric or Reality? Peripheral Status of Women’s Bureaux in the Korean Gender Regime

- 4 Continuity and Change: Comparing Work and Care Reconciliation of Two Generations of Women in Taiwan

- 5 Gender, Social Policy and Older Women with Disabilities in Rural China

- 6 Confucian Welfare: A Barrier to the Gender Mainstreaming of Domestic Violence Policy in Hong Kong

- 7 Emerging Culture Wars: Backlash against ‘Gender Freedom’ (Jenda Furi in Japanese)

- 8 Prime Ministers’ Discourse in Japan’s Reforms since the 1980s: Traditionalization of Modernity rather than Confucianism

- 9 Conclusion: Confucianism or Gender Equality?

- Index