eBook - ePub

Wage-Led Growth

An Equitable Strategy for Economic Recovery

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume seeks to go beyond the microeconomic view of wages as a cost having negative consequences on a given firm, to consider the positive macroeconomic dynamics associated with wages as a major component of aggregate demand.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Wage-Led Growth by Engelbert Stockhammer, M. Lavoie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Wage-led Growth: Concept, Theories and Policies1

Marc Lavoie and Engelbert Stockhammer

1.1 Introduction

The subprime financial crisis that started in 2007 and which became the global financial crisis challenges economists and policy-makers to reconsider the theories and policies that had gradually been accepted as conventional wisdom over the last thirty years. It is widely recognized that the global financial crisis has called into question the efficiency and stability of unregulated financial markets. This chapter argues that it has also demonstrated the limitations and even falsehood of the claim that wage moderation, accompanied by more flexible labour markets as well as labour institutions and laws more favourable to employers, will ultimately make for a more stable economy and a more productive and dynamic economic system.

The introductory chapter has recalled that in a large number of countries the past decades have witnessed falling wage shares and a polarization of personal income distribution. As will be argued in the next chapter, we believe that these phenomena are, at most, only partially associated with technical change and changes in the composition of output, and that the essential cause of the long-run evolution of income distribution and its rising dispersion is the change in economic policies and in the institutional and legal environment that has been more favourable to capital and its high-end supervisory employees over the last thirty years or so.

It is time to reconsider the validity of these pro-capital distributional policies, and to examine the possibility of an alternative path, one based on pro-labour distributional policies, accompanied by legislative changes and structural policies that will make a wage-led growth regime more likely, that is, pursue what we call a wage-led growth strategy, which, in our view, will generate a much more stable growth regime for the future. This issue is particularly important in view of the fact that the financial crisis has plunged many economies in recession, thus further weakening the ability of workers to resist attempts to lower wages or real wages, and hence with the consequence, at the macroeconomic level, of further reducing the wage share in national income.

The advocacy of a wage-led economic strategy has a long history. It has been articulated in reformist visions within the labour movement and in nineteenth-century economics the phenomenon was discussed under the heading of ‘underconsumption’.2 Within the Marxist tradition, underconsumption theories have been discussed as problems in the realization of profit.3 These ideas received a further boost from their endorsement by Keynes, when he proposed his theory of effective demand, arguing that excessive saving rates, relative to deficient investment rates, were at the core of depressed economies. In the more recent academic debate, post-Keynesian economists have done the most to analytically clarify the relation between income distribution and effective demand.4 More recently, the policy-oriented concept of a wage-led growth strategy was prominently used by UNCTAD (2010, 2011).

A standard objection to the consideration of the underconsumption thesis, or the consideration of problems related to the lack of effective demand, is that long-run growth – the trend rate of growth, also called the potential growth or the natural rate of growth – is ultimately determined by supply-side factors, such as the growth rate of the labour force and the growth rate of labour productivity. While adepts of the so-called ‘endogenous growth theory’ will recognize that investment in human capital or research and development may end up modifying the potential growth rate, they usually set aside the idea that actual growth rates could have an influence on potential growth rates. Yet, since the advent of the global financial crisis, government agencies and central banks in many industrialized countries have lowered their forecasts of long-run real growth, thus demonstrating clearly that weak aggregate demand does have an impact on potential growth. As Dray and Thirlwall (2011, p. 466) recall, ‘it makes little economic sense to think of growth as supply constrained if, within limits, demand can create its own supply’. This explains why we shall focus on the income distribution determinants of aggregate demand, paying less attention to the supply-side factors.

The main objective of the present chapter is to provide an accessible introduction to the topic of a wage-led growth strategy for policy-makers. Another important objective is to present the overarching framework underlying the efforts of the authors of the other chapters of the book, thus also providing an introduction to the notions of wage-led and profit-led economic regimes, in the hope that other researchers will adopt these distinctions and embark on the kind of empirical research required to assess whether various other individual countries or regions are in a wage-led or a profit-led regime.

In the next section, section 1.2, we provide a policy-oriented framework for the analysis of the interaction between distribution and growth. We will need to make a distinction between distributional policies and a macroeconomic regime. It is important to make these conceptual definitions and distinctions because they are not always obvious to non-economists. On the one hand governments can pursue pro-labour or pro-capital distributional policies, which aim respectively to increase or decrease the share of wages in national income; while on the other hand we have wage-led and profit-led economic regimes, which are associated with the structural macroeconomic features of the country under investigation. More technically, distributional policies are about the determinants of income distribution, the economic regime is about the effects of changes in income distribution on the economy. We will also see how policies and regimes can interact to create either stable and high growth processes or whether some combination can lead instead to slow or unstable growth processes.

In section 1.3, we shall examine why an economy would exhibit a wage-led economic regime, looking both at supply-side effects, that is the relationship between the share of wages and labour productivity growth, and also demand-side effects, which is our main concern in this section and in this chapter. Section 1.4 provides a summary of the key empirical findings regarding demand and productivity regimes. Finally, section 1.5 argues that since the world economy as a whole is likely to be in a wage-led regime, an economically sustainable process of growth requires the adoption of a wage-led strategy, with pro-labour distributional and structural policies. This will generate a wage-led growth process, which will ultimately be favourable to all concerned, including employers.

1.2 Distribution and growth: A conceptual framework

The relation between distribution and growth had been at the centre of macroeconomic analysis in classical economics, but with the dominance of neoclassical economics in the twentieth century, issues of distribution have been neglected, since income distribution was assumed to be regulated by marginal productivity relations within a perfect competition model, with wages for various occupations being determined by the pure market forces of supply and demand. But such a mechanical model of wage determination and income distribution does not hold up in a world where monopsonist features, imperfect competition and economic and social power come into play.5 In such a world, in contrast to the ideal world of market fundamentalism, market forces do not produce optimum results and there is room for modifying income distribution. In the following we offer a policy-oriented framework to analyse the relation between distribution and growth. We start by contrasting pro-labour and pro-capital distributional policies.

1.2.1 Pro-capital versus pro-labour distributional policies

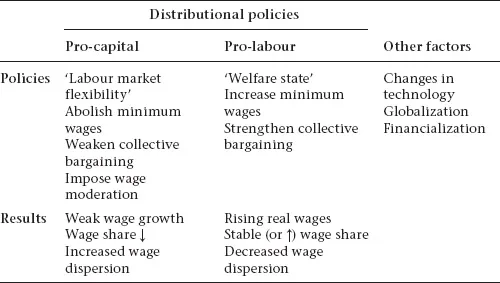

Income distribution is the outcome of complex social and economic processes, but governments directly influence it by means of tax policy, social policy and labour market policy. As shown in Table 1.1, we define as pro-capital distributional policies those policies that lead to a long-run decline in the wage share in national income, while pro-labour distributional policies are policies that result in an increase in the wage share. Pro-capital distributional policies usually claim to promote ‘labour market flexibility’ or wage flexibility, rather than increasing capital income. They include measures that weaken collective bargaining institutions (by granting exceptions to bargaining coverage), labour unions (for example, by changing strike laws) and employment protection legislation, as well as measures (or lack of measures) that lead to lower minimum wages. There are also measures that alter the secondary income distribution in favour of profits and the rich, such as exempting capital gains from income taxation, or reducing the corporate income tax. Ultimately, pro-capital policies impose wage moderation.

Pro-labour policies, in contrast, are often referred to as policies that strengthen the welfare state, labour market institutions, labour unions, and the ability to engage in collective bargaining (for example, by extending the reach of bargaining agreements to non-unionized firms). Pro-labour policies are also associated with increased unemployment benefits, higher minimum wages and a higher minimum wage relative to the median wage, as well as reductions in wage and salary dispersion. All else being equal, with a pro-labour distributional policy, the wage share will remain constant or will increase over the long run, as real wages grow in line with labour productivity or exceed productivity. By contrast, in the case of a pro-capital distributional policy, real wages will not grow as fast as labour productivity.

Of course, there are also other factors influencing income distribution, such as technological changes, trade policy, globalization, financialization and financial deregulation. These factors have recently played an important role (Stockhammer 2013), but we will not elaborate on them here, as we wish to focus on the interaction of distributional policies and economic regime.

1.2.2 Profit-led versus wage-led economic regimes

So far we have considered the economic policies pursued by a government, which could alter income distribution in favour of profits or of wages or the median wage. Next we consider the following question: knowing that income distribution is shifting in favour of profits or wages, what is the effect of such a shift on economic performance? For instance, if income distribution in a country is shifting in favour of profit recipients, does this by itself have favourable consequences on aggregate demand in the short run, on the growth rate of aggregate demand in the long run, or on the growth rate of labour productivity? If indeed this shift towards profits has favourable repercussions on the economy, as we have just defined them, then we shall say that this economy is in a profit-led economic regime. If not, if the shift towards profits has a negative impact on the economy, then the economy is in a wage-led economic regime. By symmetry, we can argue that economies that, all else being equal, experience rising wage shares that induce a favourable outcome are part of a wage-led regime, while rising wage shares that generate an unfavourable outcome indicate the presence of a profit-led regime. This is all summed up in Table 1.2. At this stage, we do not attempt to distinguish between demand and productivity effects, but only discuss the economic regime, assuming for the moment that demand and productivity react in a similar direction to distributional changes. We shall tackle this issue in more detail in the next section.

Table 1.1 Pro-labour and pro-capital distributional policies

Whether an economy is under a profit-led or a wage-led regime is affected by the structure of the economy. It will depend in part on the existing income distribution in the country, but also on various behavioural components, such as the propensity to consume of wage earners and recipients of profit incomes, on the sensitivity of entrepreneurs to changes in sales or in profit margins, and on the sensitivity of exporters and importers to changes in costs, foreign exchange values, and changes in foreign demand, as well as the size of the various components of aggregate demand – consumption, investment, government expenditures and net exports. While an economic regime also depends on the various economic structures and institutions, as well as various forms of government policy, it should be clear that the nature of the economic regime as defined in Table 1.2 is not a choice variable for economic policy in any straightforward sense. It should not be understood as designed by economic policy, but rather as determined by the institutional structure of the economy.

We can now bring together the analyses of distributional policies and of economic regimes, as shown in Table 1.3. Between the two sets ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Wage-led Growth: Concept, Theories and Policies

- 2 Why Have Wage Shares Fallen? An Analysis of the Determinants of Functional Income Distribution

- 3 Is Aggregate Demand Wage-led or Profit-led? A Global Mode

- 4 Wage-led or Profit-led Supply: Wages, Productivity and Investment

- 5 The Role of Income Inequality as a Cause of the Great Recession and Global Imbalances

- 6 Financialization, the Financial and Economic Crisis, and the Requirements and Potentials for Wage-led Recovery

- Index