eBook - ePub

Shakespeare, Cinema and Desire

Adaptation and Other Futures of Shakespeare's Language

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Shakespeare, Cinema and Desire explores the desires and the futures of Shakespeare's language and cinematographic adaptations of Shakespeare. Tracing ways that film offers us a rich new understanding of Shakespeare, it highlights issues such as media technology, mourning, loss, the voice, narrative territories and flows, sexuality and gender.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shakespeare, Cinema and Desire by S. Ryle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Something from Nothing: King Lear and Film Space

Then in the number let me pass untold,

Though in thy store’s account I one must be:

For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold

That nothing, me, a something sweet to thee.

Though in thy store’s account I one must be:

For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold

That nothing, me, a something sweet to thee.

(Sonnet 136: 9–12)

Ex nihilo

In King Lear, Shakespeare accords nothingness an especially privileged epistemological position. The concept is introduced to the play by Cordelia. ‘Nothing, my lord’ (1.1.87) is all she will say when prompted to describe her love for her father: ‘Nothing’ (1.1.89). Twice she repeats her negation, and twice Lear intones Aristotle’s formula: ‘Nothing will come of nothing’ (1.1.90); ‘nothing can be made out of nothing’ (1.4.130). For William Elton this indicates Shakespeare’s interest in medieval and Renaissance debates concerning the correspondence between the Christian notion of Creation ex nihilo, formulated at the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, and Aristotle’s dictum ex nihilo nihil fit (1966, 181). Yet if Shakespeare touches on Aristotle, he is surely uncommitted to the philosopher’s formula. For one, the doubling repetition of each protagonist’s ‘nothing’ in the play’s first act indicates the fecund growth that Shakespeare’s language will come to associate with nothingness.

This fertile relation recurs in the connection that Lear’s nothings draw with the Platonic medieval theory of kingship, The King’s Two Bodies, that circulated as legal doctrine during the Tudor and Jacobean periods. In Shakespeare’s monarchs the body natural constantly faces the crisis of separation from the political apparatus of the body politic. Without the symbolic structure of monarchy to fix his identity, King Lear is, as the Fool puts it, ‘an 0 without a figure’ (1.4.183–4). The body natural without the body politic to fix its meaning becomes nothingness: a void that has opened in the separation of matter from its symbolic governance. Reversing Aristotle, Shakespeare positions Lear outside his kingship as an abject residue to the symbolic order: nothing that has arisen from something. In his fading, uncertain sense of his identity, Lear later implores: ‘Who is it that can tell me who I am?’ (1.4.221). As Frank Kermode has suggested, the ‘shadow’ (1.4.222) of the fool’s answer, as the opposite of substance, offers another figure of nothing (2001, 190). Yet in the shadow something beyond nothing remains, an impression or silhouette of identity – just as in Puck’s Platonic suggestion, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, of the performers and the mimetic presentation as ‘shadows’ (5.1.417). In the earlier play the theatrical performance depicts itself as an affective remainder – a trace of something. But in King Lear, Lear’s body is the remainder. As homo sacer, or bare life, in Giorgio Agamben’s (2004, 38) phrase, Lear’s body lives on beyond its symbolic identity.

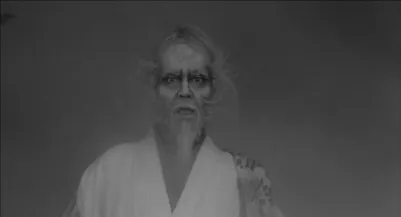

Akira Kurosawa’s Ran (Chaos) (1985) offers a powerful interpretational intervention into this Shakespearean remainder. As I discuss further at the close of this chapter, Kurosawa’s transtextual transposition involves the realignment of certain roles. Kurosawa’s Lear figure, an ageing war-lord, Hidetora Ichimonji (Tatsya Nakadai), has three sons: Taro, Jiro and Saburo. This gender alteration is due to the fact that, as Michael Wood notes, ‘no Japanese equivalent existed for such public authority being given to women’ (2005, 83). Replicating Goneril and Regan’s betrayal of Lear, Hidetora’s elder sons make war on their father. While he looks on from the tower of Saburo’s castle, the combined forces of Taro and Jiro storm the fortress. In one unflinching sequence, as Taro’s and Jiro’s soldiers slaughter Saburo’s men, a nine-minute montage surveys the horrors of war. Intercut shots of a catatonic Hidetora depict his sons’ betrayal as a treason that shakes his identity to its very core. Soldiers storm the building, killing the remaining guards loyal to Hidetora. As they shoot burning arrows into the tower, Hidetora prepares himself for ritual suicide.

In this catalogue of chaos, brutality and betrayal, Kurosawa constructs a narrative world in which there is no longer any reason for Hidetora to exist. However, searching frantically about the bloody bodies strewn throughout the tower, Hidetora cannot find a sword to end his life. In despair he sinks to the floor, indifferent to the burning arrows that whistle about him. It is to be understood as a moment of symbolic death. When he emerges from the swirling smoke of the burning castle a few moments later, his body has transformed into something undead: a remainder that lives on beyond symbolic death (Figure 1.1). The yellow and red banners of Taro’s and Jiro’s soldiers divide as Hidetora staggers between them, inscribing his in-between status in film space (Figure 1.2). As flames roar and spurt from the castle in a spectacular pictorial encapsulation of chaos, the suddenly silenced armies back away. Whether or not they believe he is a ghost, as a residue in the place of loss his figure has taken on fearful and uncanny dimensions. The soldiers closest to him lower a forest of tentative spears as he moves slowly between their massed ranks and out of the castle portal. At a seminar delivered three years after Kurosawa filmed his first Shakespeare adaptation, Throne of Blood (1957), Lacan had claimed that when Lear renounces his throne he enters ‘a limit zone […] between life and death’ (1992, 335 and 375; 1973, 317 and 353). Filmed twenty-five years later, four years after Lacan’s death, Hidetora’s blank eyes drained of life, his bleached face appearing from the smoky haze, his sagging posture and his gait heedless as the massed soldiers divide before him supplied the haunting image of a human form that has entered this ‘limit zone’.

Figure 1.1 Hidetora emerges from the smoke, Kurosawa (1985).

Figure 1.2 The soldiers divide, Kurosawa (1985).

Kurosawa’s sequence describes with unusual visual force the precarious, uncanny identity of the ruler stripped of power. This figure recurs in Shakespearean drama. Confronted with the loss of his monarchy, Richard II stages a ceremonial dethroning to ‘undo myself’ (4.1.203). Following Bolingbroke’s demands that he resign his office, Richard’s linguistic confusion indicates how his selfhood is bound by symbolic forms to the kingship: ‘Ay, no; no, ay; for I must nothing be’ (4.1.201). The homonym of ‘ay’ and ‘I’, catches the way that in agreeing to Bolingbroke’s demand Richard loses himself. Just as the substance of Lear stripped of the symbolic strictures of kingship constitutes nothing, Richard as ‘nothing’ emerges from the ‘ay’ that would cancel the ‘no’ and, therein, efface his ‘I’. Shakespeare develops the affective and aesthetic topology of nothingness in King Lear, but in Richard II’s most striking images his language prefigures this emergence of nothingness. To assuage her tears at the king’s departure, Bushy advises the queen to think of her grief as those anamorphic perspectives ‘which, rightly gaz’d upon,/ Show nothing but confusion’ (2.2.18–19). Similarly, the ‘hollow crown/ That rounds the mortal temples of a king’ (3.2.160) prefigures the topology of emptiness that Richard will come to feel he embodies, just as that nothingness is later ceremonialized by the ‘brittle glory’ (4.1.288) of his mirrored reflection that Richard smashes at his deposition. As Richard Pye has it, in Shakespearean drama ‘The king manifests the symbolic in its pure form, as a function of negation’ (1998, 177). From Richard II to Lear mad on the heath, Shakespeare’s monarchs are forced to perceive, in their own persons, Hamlet’s idea that ‘The King is a thing […] Of nothing’ (4.2.27–9).

The struggles of these monarchs with their own reduction to nothingness argue against dismissive readings of Lear’s nothing, such as Empson’s and Paul Jorgensen’s – each of whom finds, like Aristotle, that ‘nothing […] does not add up to anything’ (Empson, 1951, 139).1 One also notes the Renaissance humanist tradition of nothing paradoxes that, for Rosalie Colie, Shakespeare ‘submerges beneath the moving surface of the play’ (1966, 466). As an example of the everyday cultural currency accorded to nothingness in early modern England, take ‘the void’: the sugary desert commonly consumed during Elizabethan and Jacobean feasting. The topology of emptiness that fascinated Renaissance England is concisely evidenced by the popular practice, after the heavy meat courses, of the consumption of an ornamental, wafer-thin dessert fashioned from moulded sugar and spices, which often took the form of animals or birds. Moulds were even shaped and coloured to resemble the baked meats of the previous courses. Patricia Fulmerton notes, ‘void food was primarily for the eye: a façade food’ (1991, 126). A key moment in the ceremony, which itself was termed ‘the void’, was the cracking open of the pure appearance to reveal the empty interior. By the seventeenth century voids were usually consumed in a room separated from the feast, or even a separate building, that was also itself termed ‘the void’.

The void as temporarily fashionable collaborative behavioural practice involved adapting the procedures of formal dining to ceremonialize an encounter with nothingness. In its most evolved form, substantial culinary and architectural investments were required to elicit its pleasure. Despite the fact that it was named after its emptiness, the force of the void’s appeal was bound to the way its nothingness was concealed beneath a deceptive surface effect. Offering, in its more developed forms, a surface-level mimicry of the meat course, the theatricality of void food, and the visual pleasure that it elicited, came to invoke its supplemental relation to the earlier courses of the meal. Like the smashed mirror that ceremonializes Richard’s deposition, or Lear’s heart that he feels will ‘break into a hundred thousand flaws’ (2.2.477), the climactic moment of the void desert came when the diners cracked the sugary surface to reveal its emptiness within. Just as the theatre in early modern London offered a mimetic account of various historical figures, the void repeated, or restaged, that which was no longer; returning, in the emptiness beneath the mimesis, that which has been lost in the form of loss.

We do not know whether Shakespeare ever consumed void food. Certainly, a similarly self-conscious set of concerns with the mimetic reduplication of the loss as loss are important to King Lear. Frequently Shakespeare positions the theatrical performance as a mimetic space fashioned out of emptiness. The ‘wooden O’ (Henry V, prologue, line 13), site of the platform stage which for Jonathan Goldberg makes ‘something out of nothing’ (1984, 135), represents ‘airy nothing’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1.16), so as to recount a ‘tale’ with the quality of ‘signifying nothing’ (Macbeth, 5.5.28). The affective and ethical significance of this nothing-space is developed in Edgar’s protection of his father in his vivid invocation of Dover Cliff:

Come on, sir, here’s the place. Stand still: how fearful

And dizzy ’tis to cast one’s eyes so low.

The crows and choughs that wing the midway air

Show scarce so gross as beetles. Half-way down

Hangs one that gathers samphire, dreadful trade;

Methinks he seems no bigger than his head.

The fishermen that walk upon the beach

Appear like mice, and yon tall anchoring barque

Diminished to her cock, her cock a buoy

Almost too small for sight. The murmuring surge

That on th’unnumbered idle pebble chafes,

Cannot be heard so high. I’ll look no more,

Lest my brain turn and the deficient sight

Topple down headlong. (4.6.11–24)

Shakespeare’s language of the cliff foregrounds the way the early modern theatre used language to define narrative space. Kent’s encouragement of Lear to enter Poor Tom’s hovel – ‘Here is the place, my lord’ (3.4.1) – functions almost exactly as Edgar’s first invocation of the cliff: ‘Come on, sir, here’s the place’. Both refer to textualized spaces, but in the context of the narrative the place of the hovel is intended as real, whereas the cliff is false. In 14 of the most spatially evocative lines of verse in all Shakespearean drama, Edgar’s depiction of the cliff lays bare the techniques used by early modern drama to sustain its mimetic spaces. This places the audience’s relation to theatrical space as parallel to blind Gloucester’s desire for the cliff. In losing his eyes, Gloucester is able to engage with the nothing-space of Dover more fully than any other character in the play (to the extent that he attempts literally to throw himself into Edgar’s poetry). ‘I stumbled when I saw’ (4.1.21), he says, yet at Dover it is his blindness that allows him to be deceived.2

With this nothing-space Shakespeare rethinks the significatory limits of mimetic language that are of recurring concern in early modern poetry. Coming to sixteenth-century England through the Petrarchan tradition, the neo-Platonic struggle with transcending representational limits is central to the earliest Tudor sonnets, in impossible quests such as for ‘the wind’, which in writing verse Sir Thomas Wyatt sought ‘in a net […] to hold’ (527). Wyatt bemoans his inability to touch on his quarry, but in Shakespeare’s language this impossible quest becomes the space of emotional propinquity. The protective nothing-space of Dover Cliff is repeated in the fantasy prison in which Lear imagines a future of proximity with Cordelia at the end of the play: ‘We two alone will sing like birds i’the cage’ (5.3.9). In both of these non-spaces, Shakespeare binds a mimetically destabilizing exploration of the theatre’s verbal spaces to a deepening of the emotional proximity of his characters.

This emotional proximity is part of the unstable relation between language and nothing in the play. Eagleton notes that ‘How real is the signifier is a question […that Shakespeare] constantly poses. Language is something less than reality, but also its very inner form’ (1986, 12). Outside the symbol is nothingness. Stripped of his power by the numerical reduction of his knights to zero, Lear’s nothingness comes of his separation from the symbolic mandate of kingship. Yet, as the final section of this chapter explores, with the perspectival descent down Dover Cliff, Edgar’s sketch of nothing-space positions the signifier itself as a void, or vanishing point. For the king, nothingness is only to be evaded by keeping within the delimitations of the source of nothingness: the signifier. Indicative of the strong connections between Shakespearean and modern epistemologies, Lacan’s theory of the real posits a similarly chiasmatic formula. In acceding to the symbol, the infant’s world is punctured with an absence at the outset of his/her language use and subjectivity. Lacan writes: ‘The cut made by the signifying chain is the only cut that verifies the structure of the subject as a discontinuity in the real’ (1996, 678; 1966, 801). The real is the primordial, pre-symbolic matter of the body and the world that is punctured by the nothingness of the signifier. But, from the perspective of symbolic subjectivity, the real takes the position of a void excluded from the symbol’s governance. Divided from his own instincts, man is to be understood as fundamentally fissured: ‘a discontinuity in the real’. This movement from topography to the culturally constructed space of topology brought about by language reworks Freud’s notion of the inevitable discontent of civilized man. The wound of that which has been lost with speech marks the limit of the symbol’s ability to name, and plants an existential dissatisfaction, a yearning for something else, at the heart of man. This dissatisfaction Lacan terms desire: that fact that the inaccessible primordial substantiality, the real, has (within the symbolic horizon of meaning) come to denote nothingness. Lacan’s model suggests how, beyond their baroque play, Shakespeare’s nothings depict something vital in the relation of language, identity and desire.

As Kurosawa’s images exemplify, Shakespeare’s nothings resonate forcefully with the concerns of modernity.3 Take Derrida’s idea: ‘Il n’y a pas de hors-texte’, ‘there is nothing outside of the text [there is no outside-text]’ (1997, 158). Derrida clarifies what he means by this much-cited phrase (which follows from his analysis of Rousseau, but is intended to resonate much more widely): ‘there have never been anything but supplements, substitutive significations which could only come forth in a chain of differential references […] what opens meaning and language is writing as the disappearance of natural presence’ (1997, 159). Human comprehension and communication can only ever be significatory, occurring as a set of differential syntactic relations. If we attempt to turn our thoughts towards ‘natural presence’, we must pass through linguistic structure. As Lear’s loss of his body natural demonstrates, our relation with natural presence is by necessity mediated through language systems; that is, made unnatural, an ‘absent presence’ (Derrida 1997, 155). Outside the substitutive significations of his kingship, Lear is nothing.

Twenty years earlier the first poststructuralist, Lacan, had similarly argued: ‘the word […] is a presence made of absence’ (1996, 228; 1966, 276). As with the image of mimesis as an elusive hind that ‘fleeth afore’ in Wyatt’s sonnet, the world is posited by language as that which, in its unmediated form, is constitutionally inaccessible. This is why Lacan claims, seemingly with King Lear in mind: ‘If a man who thinks he is a king is mad, a king ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Shakespeare, Cinema and Desire

- 1 Something from Nothing: King Lear and Film Space

- 2 Body Space: The Sublime Cleopatra

- 3 Ghost Time: Unfolding Hamlet

- 4 Re-nascences: The Tempest and New Media

- Epilogue: Futures of Shakespeare

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index