eBook - ePub

The Limits to Capital in Spain

Crisis and Revolt in the European South

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Limits to Capital in Spain

Crisis and Revolt in the European South

About this book

Spain is at the epicentre of a crisis that threatens the future of the Eurozone. This book explains the deep historical and structural roots of the current crisis in Spain. It analyses the nexus between European circuits of financial capital, urbanisation, and the emergent dynamics of state austerity and popular revolt.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Limits to Capital in Spain by G. Charnock,T. Purcell,R. Ribera-Fumaz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Limits to Capital

This chapter lays the theoretical groundwork for the analysis that follows in the next four chapters. In it, our overriding concern is to explain the necessity of crisis in capitalism, the periodic appearance of crisis in the form of the overaccumulation of capital, and the relation between crises of overaccumulation and the transformations in production and patterns of social reproduction witnessed across much of the world since the 1970s – culminating in the current crisis. The chapter is organised as follows: First, we elaborate upon Marx’s analysis of capital as a process – one of self-expanding value – and the importance of inter-capitalist competition as a ‘coercive law’ that results from the formation of the general rate of profit across different branches of production. Competition impels individual capitalists to play their part in the continuous, ‘leapfrogging’ technological and organisational revolutions characteristic of capitalist production, a process marked by the uneven development of the forces of production. We explain why there is a general tendency toward overproduction in capitalism, and the relation between money, the credit system, and crises of overaccumulation. We then introduce our understanding of the social constitution of national states that together mediate the global unity of capitalist production. Here, we develop the notion that the national state itself should be understood in processual terms, and as an active ‘moment’ in the global accumulation of capital and in crisis formation and management. We follow this with a discussion of the uneven development of global production, the general tendency toward a new international division of labour since the 1960s, and how cycles of overaccumulation and crisis since then have been characterised by the spectacular expansion of credit and debt on a global scale. Throughout this chapter, our analysis remains at a relatively general and abstract level. In Chapter 2, we shift our focus to the specificities of capitalist development in relatively late industrialising countries, and Spain in particular.

The accumulation of capital and the ‘coercive laws’ of competition

Since the emergence and consolidation of the capitalist mode of production on a world scale, the general mode by which social-ecological processes combine to reproduce the means of human social reproduction itself has had its basis in a material process – that of the production of commodities. As Marx explains in the infamously difficult opening chapter of Capital (1976), a commodity is the embodiment of two potentialities: that of being socially useful and of being exchangeable for other such commodities for the right price. The secret to the commensurability of the exchange value of commodities lies in their being forms of (or the mode of appearance of) value. Value mediates the unity of all concrete, independent, and private acts of social labour within the capitalist mode of production, and therefore social-ecological metabolism in general. Marx names the substance of value ‘abstract labour’, since the expenditure of concrete labour time by so many individuals appears as the same general and undifferentiated social labour time – congealed in the form of commodities as the products of that social labour. The magnitude of value is determined by the socially necessary labour time for its production – the average measure of the entirety of private and independent concrete acts of productive activity required to produce the (material and moral) means of human social reproduction. Value therefore has no corporeal materiality; one cannot touch it, as it were. Rather, value is expressed in its most developed concrete form as money (Starosta, 2008: 310). As such, money is ‘the most abstract form of private property’ – ‘the supreme social power through which social reproduction is subordinated to the reproduction of capital’ (Clarke, 1988: 13–14).

But what is ‘capital’, in this sense? The private and independent manner in which commodities are produced is a general organisational principle that is historically specific to capitalism (Iñigo Carrera, 2008: 10–11). In capitalism, the production process itself generally consists of a series of transformative moments in which money is invested in a labour process (specifically to purchase means of production and labour-power) with the motive of exchanging the commodities produced for the original sum outlaid plus a surplus which is realised once they are sold in their intended market. The capitalist, as proprietor of the means of production, receives the original money outlaid plus a profit (an outcome which appears as if it were entirely down to her or his own ingenuity and effort). It follows from Marx’s analysis of production that capital ought to be properly conceptualised not as a thing or a ‘factor’ of production – as is the case in neo-classical economics – but as a process (Harvey, 1982: 20); capital is value-in-motion, or ‘self-valorising’ value (Marx, 1976: 994).

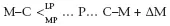

The various metamorphoses of value-in-motion can be represented in the formula for the circuit of capital:

In this, ‘M’ is money; ‘C’ is commodities; ‘LP’ is labour-power; ‘MP’ is means of production; ‘P’ denotes the combination of LP and MP in production; ‘M’ is the original money outlaid; and delta (Δ) denotes a surplus that accrues to the capitalist in the form of profit.

Harvey’s distillation of Marx’s analysis of this circulation process into ten core features, summarised in Box 1.1, suffices for now to present the fundamentals of Marx’s analysis of it, as it unfolds in the course of the three volumes of Capital. It attests to how Marx’s analysis of commodity production first necessitates the discovery through dialectical analysis of the value-form, and therefore how it penetrates the categorical presuppositions and fetish character of classical political economy and neo-classical economic theory, avant la lettre (Heinrich, 2012: 33). Crucially, of course, Marx also explains how the source of profit (ΔM) for the industrial capitalist is surplus value: the appropriation of unpaid labour time from the workforce. So, we can explain how the production of value in the process of circulation requires a class society consisting of buyers and sellers of labour-power – the only commodity, peculiar to the capitalist mode of production, whose specific use-value is the capacity to produce more value than it itself costs to produce – a surplus of value. And, further, that the total surplus value available to the capitalist class is derived from the realisation of the surplus labour time produced over and above the necessary labour time expended by social labour. We can then draw out the necessary but contradictory and ‘irrational’ features of the production of value, the necessarily accumulative character of the circulation of capital, and of capitalists’ relentless pursuit of profit.

Marx shows how the production of a particular form of relative surplus value is key to understanding not only the historical and territorially expansive development of capitalism but also its inherent tendency to enter periodic crises. It is therefore worth considering how this form of surplus value is produced. Relative surplus value is a counterpart to absolute surplus value. The latter is produced by the extension of the working day beyond the socially necessary period required to produce the use values necessary for the reproduction of the average labourer and therefore of their labour-power.1 Relative surplus value, on the other hand, arises most effectively out of enhancements in the productivity of labour-power achieved through technological innovation and its application to the labour process, and by investing in the increased scale of production. Such enhancements in the forces of production increase the mass of use values produced in a given period of labour time, thereby making innovation attractive to individual capitals seeking to realise surplus profits by producing a greater mass of commodities than their competitors, and in the same timeframe. But, given that one turnover of capital results in a fresh surplus (ΔM) – which must be reactivated as capital if more surpluses are to be accumulated and if the capitalists are to reproduce themselves as such – the development of the productive forces depends less upon the volition and entrepreneurial spirit of the capitalist than upon the competitive pressures on their rate of profit as other capitalists adopt similar technological and organisational forms of production (Clarke, 1994: 238; Harvey, 2010a: 165–9; Heinrich, 2012: 106–8). Marx’s original contribution here was to reveal that constant revolutions in the development of the forces of production are necessary to the process of the accumulation of capital as undertaken by the capitalist class: ‘the development of capitalist production makes it necessary constantly to increase the amount of capital laid out in a given industrial undertaking, and competition subordinates every individual capitalist to the immanent laws of capitalist production, as external and coercive laws’ (Marx, 1976: 739).

Box 1.1 Ten Core Features of the Circulation of Capital (from Harvey, 1985a: 129–32)

1. The continuity of the circulation of capital is predicated upon a continuous expansion of the value of commodities produced…

2. Growth is accomplished through the application of living labour in production

3. Profit has its origin in the exploitation of living labour in production…

4. The circulation of capital, it follows, is predicated on a class relation… [between] those who buy rights to labour power in order to gain a profit (capitalists) and those who sell rights to labour power in order to live (labourers)…

5. This class relation implies opposition, antagonism, and struggle. Two related issues are at stake. How much do capitalists have to pay to procure the rights to labour power, and what, exactly, do those rights comprise? Struggles over the wage rate and over conditions of labouring (the length of the working day, the intensity of work, control over the labour process, the perpetuation of skills, and so on) are consequently endemic to the circulation of capital…

6. Of necessity, the capitalist mode of production is technologically dynamic. The impulsion to fashion perpetual revolutions in the social productivity of labour lies, initially, in the twin forces of inter-capitalist competition and class struggle…

7. Technological and organisational change usually requires investment of capital and labour power. This simple truth conceals powerful implications. Some means must be found to produce and reproduce surpluses of capital and labour to fuel the technological dynamism so necessary to the survival of capitalism.

8. The circulation of capital is unstable. It embodies powerful and disruptive contradictions that render it chronically crisis-prone […] Growth and technological progress, both necessary features of the circulation of capital, are antagonistic to each other. The underlying antagonism periodically erupts as fully fledged crises of accumulation, total disruptions of the circulation process of capital…

9. The crisis is typically manifest as a condition in which the surpluses of both capital and labour, which capitalism needs to survive, can no longer be absorbed. [This is] a state of overaccumulation.

10. Surpluses that cannot be absorbed are devalued, sometimes even physically destroyed. Capital can be devalued as money (through inflation or default on debts), as commodities (unsold inventories, sales below cost price, physical wastage), or as productive capacity (idle or underutilised physical plant). The real income of wage labourers, their standard of living, security, and even life chances (life expectancy, infant mortality, and the like) are seriously diminished, particularly for those thrown into the ranks of the unemployed. The physical and social infrastructures that serve as crucial supports to the circulation of capital and the reproduction of labour power may also be neglected.

To sum up, the Marxian theory of value explains how the imperative to enhance the productivity of labour-power under the control of individual capitalists – and therefore to produce more cheaply than their competitors – is ‘hard-wired’ into capitalist production; and, concomitantly, the competitive pressure to match, or indeed better, the productivity of those innovating capitals on the part of those left behind cannot be withstood if the latter wish to remain profitable and, ultimately, in production. As Marx puts it: ‘The law of the determination of value by labour-time makes itself felt to the individual capitalist who applies the new method of production by compelling him to sell his goods under their social value; this same law, acting as a coercive law of competition, forces his competitors to adopt the new method… Capital therefore has an immanent drive, and a constant tendency, towards increasing the productivity of labour, in order to cheapen commodities and, by cheapening commodities, to cheapen the worker himself’ (Marx, 1976: 436–7). This adjustment process on the part of individual capitalists is the source of crisis in capitalism, since, as Clarke (1990/1: 454–5) underlines: ‘The drive to increase the production of surplus value, although imposed by capitalist competition, is not confined within the limits of the market but is subject to its own laws, which determine the tendency to expand production without regard for the limits of the market. These laws are defined not by the subjective irrationality of the capitalist, but primarily by the uneven development of the forces of production as capitalists struggle for a competitive advantage’.

The tendency toward overproduction, the necessity of crisis and cycles of overaccumulation

Since money appears in capitalist societies as some-‘thing’ that stands apart from other commodities and which bridges the gap between different moments of capital accumulation – sale and purchase, production and circulation; there always exists a formal possibility that the metamorphosis of capital might breakdown, and that capitalists might not realise the value of the commodities that they have produced (see Burnham, 2002: 125–6). Capitalists engage in production in a private and independent manner so as to realise profit (i.e., surplus money – ΔM), and the tendency of capitalist production is to develop the productive forces without limit. Therefore, there is no guarantee that supply will be met with proportionate demand. Indeed, the tendency inherent in the capitalist mode of production is toward the overproduction of commodities – a tendency borne out of the uneven development of the productive forces within and between different branches of production and, under the circumstances, imposed by competition (Clarke, 1990/1, 1994). This explains the enduring insight of Marx and Engels’ early depiction in the Communist Manifesto of capitalism as an inherently expansive system of production, forcing the opening up of new markets abroad by the compulsion of capitalists to overcome barriers to profitability experienced as competition in existing markets (Cammack, 2013; Harvey, 1988). Such endeavours – along with the aforementioned development of the productive forces – can historically explain boom-like periods of growth and expansion within and across different national capitalist societies. Yet the tendency toward overproduction is never overcome. It is evident that in the competitive struggle between capitalists, those which are unable to maintain the pace and scale of technical and organisational change will find it harder to turn a profit – their eventual liquidation leading to the further concentration and centralisation of capital in progressively fewer hands.

All capitalists experience overproduction in the form of intensified competition, as each one struggles to maintain profitability in the face of a downward pressure on prices and the devaluation of their stock and means of production. Some capitalists will invest in further technological and organisation change; others will switch their capital into new productive or speculative ventures in the hope of making profits elsewhere (as we will see in our analysis of ‘capital switching’ into Spanish real estate in Chapter 4); and the capitals left behind by the pace of technological change will look to a variety of ‘adventurous paths’, such as borrowing and even swindling, so as to guarantee their survival (Marx, 1981: 359). In each scenario, the capitalist looks to sustain her or his own reproduction regardless of the limits of the market and, in turn, plays her or his part in the extension of generalised overproduction that sooner or later presents itself to all capitalists as a limit to accumulation (usually when banks restrict loans, as we explain in further detail next). In such circumstances, profitability will only be restored through a crisis – in which, for instance, backward capitals are liquidated, stocks and machinery are devalued or scrapped, and workers are laid-off and forced to re-enter the labour market to look for jobs on new contractual bases (perhaps with lower pay or fewer guarantees regarding the terms and conditions of work). This will be illustrated in our analysis of industrial restructuring and the fragmentation of labour in Spain in the 1980s, in Chapter 3.

Given the inherent tendency to develop the productive forces without limit, and therefore toward generalised overproduction, we can therefore insist that crisis is not only a formal possibility in capitalism, but that crisis plays a necessary role in re-limiting accumulation within the confines of the market and restoring the conditions for capital accumulation. Within a mode of production in which ‘the true barrier to capitalist production is capital itself’ (Marx, 1981: 358), crisis obtains as the ‘irrational rationaliser’ (Harvey, 1982: 305). Crisis ‘is not a pathological phenomenon appearing on the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Boxes and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Limits to Capital

- 2 The Limits to Import Substitution Industrialisation

- 3 The Limits to European Integration

- 4 The Limits to Urbanisation

- 5 The Limits to the State

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index