eBook - ePub

The Power of Customer Misbehavior

Drive Growth and Innovation by Learning from Your Customers

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Power of Customer Misbehavior

Drive Growth and Innovation by Learning from Your Customers

About this book

To stay competitive, firms need to build great products but they also need to lend these products to the uses and misuses of their customers and learn extensively from them. This is the first book to explore the idea that allowing customers to adapt features in online products or services to suit their needs is the key to viral growth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Power of Customer Misbehavior by M. Fisher,M. Abbott,Kenneth A. Loparo,Kalle Lyytinen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Comunicación empresarial. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why is Viral Growth Important?

‘This is the honey badger. Watch it run in slow motion. It’s pretty badass. Look, it runs all over the place. “Woah, watch out!”, says that bird. Ew it’s got a snake? Oh, it’s chasing a jackal? Oh my gosh!’ If you read this and the voice in your head sounded like a high-pitched, effeminate male, then you’ve undoubtedly seen the YouTube video ‘The Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger (original narration by Randall)’. It was uploaded on 18 January 2011 by user ‘czg123’ and has been viewed over 56 million times.1 The video features original footage of the tough and ornery Honey badgers taken from a National Geographic special that aired in 2007.

According to the New York Observer the ‘Crazy Nastyass Honey Badger’ video was the brainchild of Christopher Gordon2 (not a guy named Randall) – an actor, writer, comedian, and ‘Randall’s Personal Asst.’3 In an email interview by Michael Humphrey, Contributor at Forbes, we learn that Gordon’s inspiration for the video came from his father’s work on Marlon Perkins’ ‘Mutual of Omaha‘s Wild Kingdom’ as a cameraman.4 Between his father’s film footage and his twice-weekly trips to the zoo with his grandmother, he developed the habit of narrating everything.

With memorable quotes such as ‘honey badger don’t give a shit’ or ‘honey badger don’t care’, the video became an instant hit. It was covered within the first 30 days by humor blogs such as ‘Funny or Die’ and ‘Huffington Post’ as well as mainstream entertainment sites like TMZ.5 The authors of this book became aware of the video in January 2011 when Marty’s friend posted the video on Facebook. He then passed it in email along to Mike and several other colleagues. Kalle (Marty and Mike’s doctoral advisor at the time) stared in disbelief, believing that the foundations of education were sure to crumble beneath him, as Marty showed the video to a group of academics between meetings. Marty singlehandedly invited dozens of people to view the video, many of whom could be seen later excitedly discussing the video amongst themselves and immediately sharing it on Facebook, or emailing a link to it to friends and colleagues.

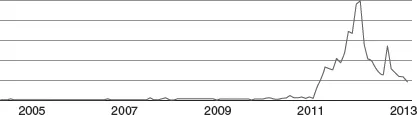

Figure 1.1 Google Search for ‘Honey Badger’6

Source: Google and the Google logo are registered trademarks of Google Inc., used with permission.

While the video became a huge Internet sensation, its attraction as an entertainment destination was short lived. Figure 1.1 shows that prior to Randall’s video, not many people were searching for ‘honey badgers’ on the web. During 2011 the interest skyrocketed, while plateauing at the end of the year. After a year in the spotlight, interest in the web search term ‘honey badgers’ started to wane, falling almost as quickly as it rose.

The Honey badger video teaches us several key points that we would like to present in this chapter about viral growth. First, it shows how ideas can spread from one individual to another very quickly. Marty alone was responsible for inviting dozens of people to view the video. Second, it helps us see the effect of virality without the power of retention. While the Honey badger video was wildly popular in 2011, by 2013 its popularity had disappeared. We’ll cover both of these points in more detail in this chapter as well as answer the question of why viral growth is important. First we need to define the term viral growth.

VIRAL GROWTH CLIFF NOTES

Viral growth is achieved when the users of a product cause, on average, more than one additional user, per existing user, to use a product or service. In other words, each user of a product influences more than one additional user to begin using the product during some specified time period. If a product has five users at the end of time period 1, it will have more than ten users using the product in time period 2, more than 20 in time period 3, and so on.

An existing user of a product influencing a friend, colleague, or relative to start using a product can occur in a variety of ways. One method is very direct. A user invites a bunch of friends to start using a product by sending an email with a link to the product. In the real world the user might send a postcard that advertises the product. Another method, that is much less direct, is that people might see another individual using the product. Before a night out, a husband might notice his wife using an online product to search for restaurants. If the next time the husband needs a restaurant he starts using that product, then his spouse has influenced him into using the product. There are as many ways as you can imagine – both directly and indirectly – to influence another user to begin using a product. Of course, marketers for years have been trying to figure out new ways for this to occur.

This provides a very high-level explanation of how viral growth occurs. For a more in-depth explanation, continue reading the next section. For those who don’t like math, or just really don’t want to understand the details of this phenomenon, skip ahead two sections in this chapter to one entitled ‘Why do we want to achieve viral growth?’, where you’ll get to read about two companies that achieved viral growth.

WHAT IS VIRAL GROWTH?

For our purposes, growth can be defined as building a user base for a product or service. If we had one user yesterday and we gain another user today we have 100 per cent growth day-over-day. The term ‘viral’ is an adjective that describes the picking up of an object or information that can induce agents possessing it to replicate it, resulting in a myriad of new copies being spread around. The etymology of the term viral dates to 1989 according to the Oxford English Dictionary. At that time it came to mean the ‘rapid spread of information’, in addition to its earlier meaning of the spreading of viruses or germs during a contagion of a disease. A viral video would thus be one that induces people to view it and share it with other people, resulting in a growing number of views. One interesting point about being viral is that it does not have to be a purposeful replication. In some instances, people might intentionally share a video with their friends, but in other situations people might see a celebrity watching a video and then view it themselves. The viewing of the video has been replicated, but not by active participation of the celebrity.

The presence of such a fast growth pattern that follows the spread of information in social networks has justified the use of the epidemiological term ‘viral growth’ to characterize these patterns. The spread of information and its consequent use in a population is like that of a virus spreading through a population. Though in their everyday life people do not intentionally spread viruses, they can figuratively do so in their social networks by sharing information about rumors, services, features, benefits of a site, or just by telling others about their positive use experiences.7 Combining these two words we can form the term viral growth that we define as the increase in the user base of a product or service resulting from people’s action to induce other people in their networks to repeat their usage of the product or service.

While viral growth has only reached the mainstream vernacular in the past decade when the hyper-growth Internet services made it popular, the idea of viral growth dates back to 1976, with Richard Dawkins’ publication of The Selfish Gene. Dawkins’ book analyzed evolution as a cultural phenomenon, where instead of genes controlling the evolution ideas called ‘memes’ would control the process. A meme is a framework for thinking about things – an idea, behavior, or style, such as wearing white after Labor Day, the phrase ‘You had me at “hello”’ from the 1996 film Jerry McGuire, or the Honey badger story. It can be anything passed from person to person where the rate of acceptance and proliferation are likely to depend on several factors such as entertainment value, news worthiness, educational value, or sheer popularity.

One significant difference between biological evolution and cultural evolution is the pace at which cultural evolution can take place. Memes can spread much faster than genes can replicate, even when compared to the very fast ten-day metamorphosis cycle of a fruit fly. In that amount of time a meme can spread around the Internet and become old news. Viral growth is achieved when a meme spreads very fast, without the conscious plan and effort to spread it. At the same time the growth in a user base will follow a power-law distribution until the adoption reaches a point of non-displacement.8

A power law expresses a mathematical relationship between two quantities in which the frequency that an event occurs varies as a power (or exponentiation) of some attribute of that event. In the case of the Honey badger video, the upward curve of Figure 1.1 (the viral growth phase) is a power of the previous viewings and subsequent shares. To achieve the sharp incline in growth, the cumulative viewers for any given day have to share (on average) the video more than once. Power-law distributions are also sometimes called scale-invariant or scale-free distributions, because a power law is the only distribution that is the same whatever scale we look at it on.9

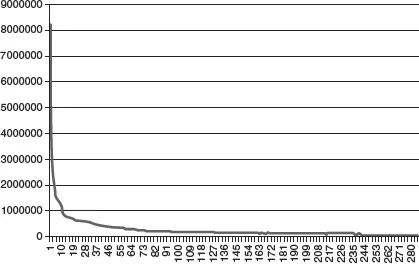

Figure 1.2 US City Populations

Few real-world distributions follow a power law over their entire range, especially for smaller values of the event. For example, the population of cities follows a power-law distribution above the minimum population of 40,000. In Figure 1.2 we have plotted the populations of the top 285 US cities according to the 2010 US Census. As you can see, a few cities have the majority of the population and then the amounts drop off quickly. The top city, New York with 8.2 million people, has three times as many people as just the third city, Chicago, with 2.7 million people.

Armed with this initial definition of viral growth and understanding of power laws, we next explore factors that define viral growth.

WHAT ARE THE COMPONENTS OF VIRAL GROWTH?

While achieving viral growth can be elusive, calculating and predicting the growth under certain conditions can be accurately determined due to well-defined structural conditions that characterize such growth. In order to do so requires acquiring and estimating information about pivotal factors that affect the spread of the information or ideas. This process of spreading is known as contagion, which can be defined as rapid communication of an influence. It is also derived from an epidemiological term relating to the spread of infectious disease.10 Contagion simply deals with the rate at which infected new users become ‘converted’ to use a particular product or service. Factors that affect contagion, as known from epidemiological studies, include first fan-out and conversion, both of which we will discuss below. For a more complete coverage of how the term ‘viral growth’ was derived from the study of contagious diseases, see Appendix A.

The viral growth of a product or service is determined by the extent to which current users send requests to their friends or colleagues to participate in a service and whether those individuals ‘convert’ and become users as well. To describe the rate of this process, Kalyanam coined the concept of a viral index11 or viral coefficient12 that predicts how quickly viral growth can occur for a service provider. The viral coefficient (Cv) predicts the number of new users that will be generated by one existing user through influencing, recommending, suggesting, sharing, and so on. It is a function o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Why is Viral Growth Important?

- 2 Technological Factors

- 3 The Viral Model

- 4 The Concept of Self-Identity

- 5 Identity and Self-Verification

- 6 Seeing and Being Seen

- 7 Getting it Right

- 8 Getting it Wrong

- 9 Conclusion

- Appendix A: Viral Growth

- Appendix B: A Short Summary of Research Informing the Book Findings

- Glossary

- Notes and References

- Index