eBook - ePub

Tribal Marketing, Tribal Branding

An expert guide to the brand co-creation process

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tribal Marketing, Tribal Branding

An expert guide to the brand co-creation process

About this book

Tribal branding allows marketers to benefit from greatly enhanced levels of consumer devotion to brands. Richardson incorporates the approach of ethno-marketing to expertly explain the opportunities for marketing and branding professionals to co-create brands with, and develop new ways of marketing to, tribal groups and brand communities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tribal Marketing, Tribal Branding by Brendan Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Tribes, Tribal Marketing, and Tribal Branding

Introduction

Imagine a scenario where everyone you want to promote your brand to is so enthusiastic about the brand that they are already promoting it to one another. Instead of a situation where jaded or cynical consumers feel a sense of apathy towards your products, they feel a sense of commitment and excitement about your product that they want to share with other people. Imagine a situation where instead of only having a small team of developers trying to generate new product ideas, you had access to a huge pool of people who continually devoted their time, energy, and love to developing new ways of sharing your product with one another? What if instead of having to devote huge resources, in terms of time and money, to bring this about, you could rely on your customers to do it for free? Is this a marketer’s utopian dream? Not at all. Welcome to the world of consumer tribes.

Tribes are not just loyal to their chosen brands – they are passionate about them. This passion means that they voluntarily become advocates for the brand, going out of their way to promote the brand to non-users. They organize events that celebrate and promote their chosen brands, thereby providing brand-related experiences that convert more consumers to devotion to those brands. They engage with one another online and offline, affirming each other in the practice of brand rituals that tie each consumer into a deeper relationship with the brand. Volkswagen Beetle owners swap stories online about the names they have come up with for their cars. Harry Potter fans reinforce each other’s loyalty to the Harry Potter brand1 by sharing anecdotes about their favourite passages in the books and encouraging each other to dress up as their favourite characters for book launches and movie premieres – helping to create a vibrant and authentic atmosphere around these events at no additional cost to the marketer.

Tribes also act as innovators, generating new product usages and concepts and ways of enhancing the product and brand experience for one another. The Nutella community post photos online to show each other the latest way to enjoy Nutella.2 Mini drivers give each other advice on better ways to keep their cars in perfect condition.3 These enhanced experiences and innovative usage practices serve in turn to renew and perpetuate the tribe’s enthusiasm for the brand – or brands, if they adopt more than one. Members of tribes can also serve as an informal product support system to one another, helping one another to resolve product bugs or glitches, in the context of friendly interpersonal relationships that bring the goals and aspirations of relationship marketing to life. Apple owners reinforce one another’s passionate perception of the brand not just through sharing their enthusiasm for the product features they find most appealing, but – crucially – through positively affecting one another’s perceptions of product quality.4 They do this not only by repeating anecdotes to one another about how much less vulnerable Apple computers are to viruses than PCs, but also by debugging glitches for one another – for free. The outcome? Instead of a feeling developing that there is a problem with the product, a perception of brand perfection is perpetuated. Then when rumours emerge of the imminent launch of the latest Apple product, the members of the tribe whip each other into a frenzy of anticipation, ensuring that the launch will be a success.

Not that tribes always form around brands. Tribes often form around activities like snowboarding or in-line skating, shared identities and concerns like parenting, TV shows like Star Trek, or hobbies like photography. However, when tribes emerge in a non-brand-specific way, members of tribes very often become a critical source of brand information for one another and when they feel that a brand is supportive of their shared identity and their sense of emotional connection to one another, they often become passionate advocates of that brand.

In short, tribes deliver on so many things that are of interest to the marketer that, when you consider they do all this without it costing the marketer anything, you have to ask – why on earth don’t more marketers learn to practise tribal branding?

So, what is tribal branding, and what makes it different from other, more conventional forms of consumer marketing? And what does the term ‘tribal marketing’ actually mean? To understand both terms – in fact, to understand both processes – we first need to take a look at some key ideas that help to clarify these processes and show how they differ from more conventional approaches to brand communication and development.

The first idea we need to take a closer look at is the whole notion of consumer tribes. What is a consumer tribe? How do consumer tribes form? Why do they form? Who are they formed by? Only by first asking and then understanding the answers to these questions can we then understand why tribes are so important for the future of consumer branding, and why tribal branding is so effective as a way of conferring authenticity on brands and differentiating them in a meaningful and lasting way from their competitors.

The origin and emergence of consumer tribes

What is a consumer tribe? Tribes are first and foremost a means whereby the contemporary consumer experiences a sense of community. Why is this so important? As Bernard Cova first explains in his initial5 discussion of consumer tribes in the European Journal of Marketing, community has taken on a new form for contemporary consumers. Even though so many traditional sources and forms of community, such as extended family or village community, have become weaker or less significant, human beings are still essentially social animals. We need to feel part of a community, or communities, because we have a fundamental need for social relationships. This is hardly news, and of course marketers have long drawn from the theories of Abraham Maslow, among others, to position brands as a means of accessing social relationships.

What increasingly differs from past experience is the means whereby we access community and feelings of belongingness. Traditionally (and I accept I am over-simplifying for the sake of brevity) consumers could derive a sense of community from ties of kin, religion, and geographic location. Identity could be constructed out of shared cultural practices, practices mutually communicated through family, through the rites of religious faith, and so on. However, in recent decades, for a variety of reasons, these traditional sources of affiliation have begun to lose their hold. The demise of organized religion and the relative demise of the nuclear family are just two of the ways in which old certainties about community and identity no longer apply. Many commentators have spoken of processes of social fragmentation that have contributed to the demise of homogenous community, as we knew it. To some extent, the effects of modernization were blamed, although it has also been observed that consumers increasingly wished to embrace their own individuality, free from the ties of tradition, organized religion, and so forth. The era of individualization – or as some called it, hyper-individualization – was born out of the desire to differentiate the self from the conventional and escape the restrictive mores and dogmas of the past. However, the fulfilment of this desire to carve out a hyper-individualized identity could not overcome the fundamental and enduring need to feel a sense of connection to others; hence the emergence of what has been termed ‘social re-aggregation’.

Social re-aggregation

According to Cova, the so-called postmodern consumer, in their desire to express and complete the self through individualized consumer identity projects, still needed to feel a sense of social connectedness. The need for community could not be so easily discarded after all. Hence in the midst of this process of hyper-individualization was a process of social re-aggregation. However, this need for social connection has manifested itself in a different way to more easily defined traditional forms of community. These new communities, or tribes, are not rigidly structured or hierarchical in nature. Instead they are founded out of a shared passion for activities or objects that people freely choose to become excited about. Rather than submitting to any obligation to comply with the rules – and restrictions – of traditional communities, members of these new communities have begun to affiliate around objects and practices of shared devotion because they choose to do so. It is, as Cova says, ‘an emotional free choice’.

Also, while Cova originally spoke about the ‘desperate search for social links’, it would be absolutely in error to conclude that these tribes are made up of dysfunctional individuals whose social isolation draws and keeps them together in some kind of desperately mutual nerd-dom. Instead, when individual consumers discover that they have something important in common with each other, the social contact experienced through shared devotion to an activity or brand becomes an important means whereby their need for community is fulfilled.

As will become apparent, this sense of shared devotion is utterly critical for the practice of tribal marketing. Tribal marketing is concerned – or at least it ought to be – with supporting the twin principles of shared devotion and the need for, not community per se, but community with a specific sense of shared – and often flamboyant – identity drawn from collectively imagined and shared emotions, practices, and values. That’s why when we speak of contemporary consumer tribes, we use the term ‘linking value’ to indicate that tribes gather together around what they collectively imagine or construct as sets of shared values, practices, and emotions, sometimes represented by tangible objects and brands, and sometimes not. As the tribal marketer’s primary role is to support tribal linking value, this concept is of real importance to the practice of tribal marketing.

Tribal linking value

This notion of tribal linking value is absolutely fundamental to the practice of tribal marketing. Tribes affiliate together first and foremost due to a sense of shared values and emotions. Whether these shared values, when scrutinized, are more imagined than ‘real’ is not unimportant, hence we will revert later on to a much more detailed consideration of the entire notion of imagined community. For now, though, the following discussion of tribal linking value will suffice.

What it comes down to is simply this. Tribes are not held together by some sort of need to remain in a community purely for the sense of social connection that this provides. Instead, the social connection stems from the shared emotion, the shared belief, that a particular object or practice really matters. If you don’t find the object or practice important, if it doesn’t render you emotional, then that’s fine, but you and I are not part of the same tribe and we won’t go on to share that social connection. If you are not excited by this activity, this person, or this brand, I don’t really want to form a social connection with you. On the other hand – if you are passionate about it, if this brand, or this activity, or this form of devotion, and what it represents really matters to you, and you are willing to engage with me in (potentially brand-related) public performance of this identity, then yes! – I do want a social connection with you. We are part of the same tribe.

This notion of shared performance brings us to another key concept that is central to an understanding of what tribes are all about – that concept is group narcissism.

Group narcissism

Because tribal identities and linking values are founded on shared passion, whether that is passion for a brand, an activity, or both, this shared passion must be demonstrated and upheld. You must show your tribal credentials and demonstrate that you too feel that the shared identity, activity, or object of devotion is personally important to you. This gives rise to the demonstrative aspect of many, if indeed not all, of these tribes. The importance of the identity is mutually affirmed through taking part, often in a highly visual way, in tribal activities. This can of course give rise to some stereotypes, such as Star Trek fans wearing full sci-fi regalia, sports fans decked out in team colours and facepaint, or Red Bull Flugtag participants wearing crazy costumes and careering off ramps in home-made ‘aircraft’ that are designed to make everyone laugh rather than make it possible for the ‘pilot’ to actually fly. This kind of ostentatious display, while not characteristic of all tribes, does serve to highlight the importance of participation. For all tribes, the imperative is to participate, so that there is something for you and everyone else to actually look at and enjoy. The only real taboo – if you wish to be a member of the tribe – is non-participation.

While this notion of group narcissism (so-called because of the collectively self-indulgent, self-fascinated, and gratificatory nature of these exhibitionistic displays) is thus central to the whole phenomenon of the consumer tribe, it would be mistaken to assume that all tribes engage in outlandish forms of playful and exhibitionistic behaviour. The dictates of group narcissism can be just as easily satisfied in ways that are much more subtle than the spectacularly public behaviours of some of the groups I have just mentioned. For the Lomography tribe, for instance, taking and sharing photos in a particular way is enough to be regarded as a legitimate member of the tribe (see Cova 1997 or www.lomography.com for more). For the Nutella tribe, it suffices to post online photos of different uses of this versatile and delicious chocolate spread! (see Cova and Pace’s 20066 study for a more detailed discussion of this particular tribe’s activities and proclivities).

In short, there are a great many variations on this theme of group narcissism and how it manifests from one tribe to the next. However, while some tribes are highly demonstrative and exhibitionistic, others may be far less so. The one key common denominator is the requirement to take part, thereby affirming the tribe’s linking values and helping to perpetuate the tribal identity.

It also follows that there is a rich diversity of forms of tribal identity. Possibly the easiest way to demonstrate this is to look at a number of examples of different tribes, before moving to the question of whether all consumer communities share the same structures and manifest the same principles as the tribes we have thus far examined.

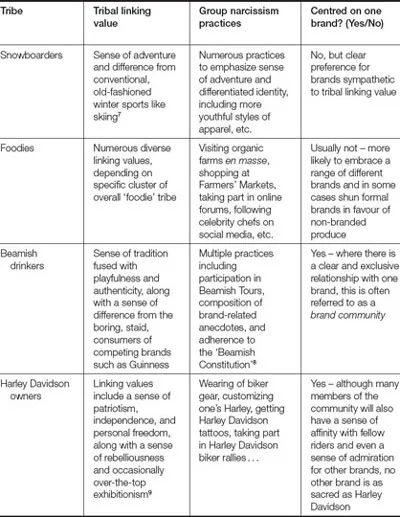

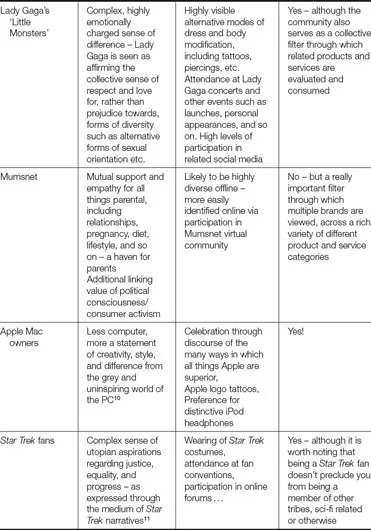

Table 1.1 therefore presents a simplified tribal typology with the names of a variety of different tribes and a summary of how they manifest (or might manifest) some of the characteristics and features we have discussed so far. In examples where there is a lack of specific research at the time of writing, I have included some examples of the likely linking value based on desk research. I’ve also indicated some examples of tribes that are potentially made up of a variety of sub-tribes or ‘clusters’ whereby certain linking values might be better explored at the level of the cluster rather than across the entirety of the more loosely defined tribe.

Table 1.1 A sample of tribes with simplified tribal typology

There are a number of things we can infer from this simple summary. First it gives us a flavour of the sheer variety of different tribes out there. There are so many other consumer tribes in existence and it would be futile to try to list them all – but we will look at some of the above tribes (and others) in more depth elsewhere in this book. Second, we can see that it is possible for people to have a sense of tribal identity that identifies a little more closely with a subset or cluster of people than with everyone in a wider tr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Tribes, Tribal Marketing, and Tribal Branding

- 2. What Is Tribal Marketing, and Why Hasn’t It Been More Widely Implemented?

- 3. Tribal Origins and Idiosyncrasies – Why Brand Tribes Form and Why They Need to See Themselves as Unique

- 4. Understanding Tribal Dynamics: Beginning to Engage with the Art of Ethno-Marketing

- 5. Collecting Tribal Data

- 6. Interpreting Tribal Data: Analysing Ethnographic Data and Using It to Build and Maintain Tribal Brands

- 7. Meet the Tribes

- 8. Towards an Ethics of Tribal Marketing

- 9. Tribes and Tribal Branding – Where Do We Go from Here?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Tribes

- Index of Topics