eBook - ePub

Environmental Sustainability in Transatlantic Perspective

A Multidisciplinary Approach

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Sustainability in Transatlantic Perspective

A Multidisciplinary Approach

About this book

Experts from business, academia, governmental agencies and non-profit think tanks to form a transnational and multi-disciplinary perspectives on the combined challenges of environmental sustainability and energy security in the United States and Germany.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environmental Sustainability in Transatlantic Perspective by Manuela Achilles,Dana Elzey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environmental Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Broader Contexts of Sustainable Development

1

Putting a Price on the Plant: Economic Valuation of Nature’s Services

Artificial trees. What will they think of next?

The industrial revolution facilitated an enormous increase in human well-being – but with some unfortunate consequences. The burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) releases carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, where it accumulates and alters climate patterns. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations are now around 390 ppm, more than 100 ppm higher than pre-industrial levels, and scientists believe this will lead to more intense storms, rising sea levels, increased flooding and droughts, and altered agricultural patterns as regions grow wetter or drier due to shifting patterns of rainfall.

Prior to the industrial revolution, carbon dioxide levels remained relatively constant. Animals inhaled oxygen and exhaled CO2, while trees and other plants absorbed carbon dioxide and emitted oxygen. As human populations have increased, they’ve cut down trees and burned greater and greater amounts of fossil fuels – this is where the artificial trees come in.

Klaus Lackner, a physicist at Columbia University, has designed carbon dioxide absorption systems – aka artificial trees – that capture CO2 a thousand times faster than real ones. It’s clear they provide real benefits – allowing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to increase unchecked is a recipe for climatic disaster – but at $30,000 apiece, the trees aren’t cheap.

The observation that nature provides goods and services of benefit to humankind is not new; she’s supplied humanity with food, fuel and fibers for millennia. Only in recent years, however, have we begun to understand and quantify the indirect benefits we receive from the natural environment (e.g. carbon sequestration services, flood protection and climate regulation). In the coming years, as we struggle with increasing levels of population and consumption, and decreasing levels of fresh water, forests and biodiversity, we will see an increased need to assign economic values to nature’s services. This chapter describes the challenges of ‘putting a price on the planet’: (1) identifying, defining and measuring specific ecosystem services, (2) valuing ecological amenities and (3) designing payment schemes to facilitate trade in nature’s services.

____________

Acknowledgments: Mike Ellerbrock and Susie White provided helpful comments.

The value of nature

Nature possesses intrinsic value (e.g. biodiversity) as well as anthropocentric benefits. Frederic Vester, a German biochemist and noted proponent of systems thinking (vernetztes Denken), was an early advocate for valuing nature in a holistic fashion. In Der Wert eines Vogels (1983), Vester observed that although the material value of a typical songbird is quite small, the services it provides to humanity are quite large. By ‘material value’, he meant the value a bird’s respective chemical components (calcium, carbon, phosphorus, etc.) might fetch on the open market; he estimated this figure at 2¢. Vester then went on to enumerate the many benefits songbirds bestow on humankind, assigning economic values to each: insect removal ($36), tree planting ($12), environmental monitoring ($60), etc. until he came to a final value of $180. In arriving at these figures, Vester used prices for similar services, arguing, for instance, that the calming influence of a songbird’s call equates to a year’s supply of Valium ($25), an anti-anxiety drug. Although extremely well-known in Germany, Vester’s work is relatively unfamiliar outside his native land.

In another notable attempt to raise awareness about the value of nature, Robert Costanza and his colleagues analysed more than 100 studies valuing 17 categories of services over a range of 16 types of ecosystems. Their results, published in the journal Nature, reported the total value of Earth’s ecosystems to be on the order of $33 trillion – about twice the then-value of the gross domestic products of the world’s nations (Costanza et al., 1997). Though criticized, this study represented a significant milestone in the valuation of nature’s services.

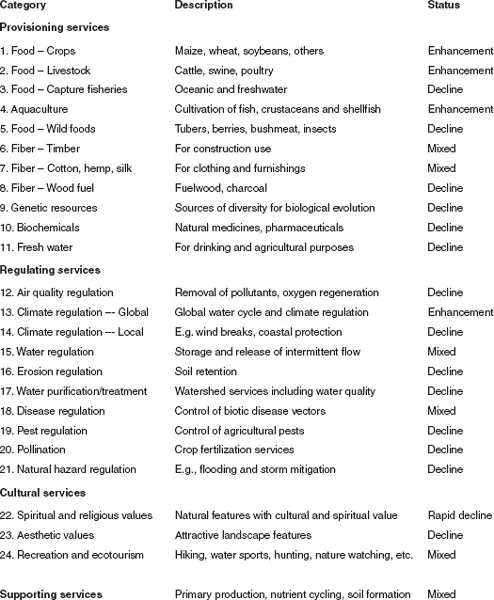

The most ambitious attempt to inventory Earth’s natural systems (although it did not assign monetary values) is the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Commissioned in 2000 by the United Nations Environment Program, the results were released in 2005 after a five-year study period involving 1,360 experts and more than 900 reviewers. The report focused on ecosystem services (i.e. services provided by natural ecosystems that contribute to human well-being). Also known as natural capital, the MEA categorized Earth’s ecosystem services (Figure 1.1) as follows:

Figure 1.1 Ecosystem services over the past 50 years

Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005).

Source: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005).

- 1. Provisioning services such as food, water, timber and fiber

- 2. Regulating services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes and water quality

- 3. Cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic and spiritual benefits and

- 4. Supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis and nutrient cycling.

The results of these efforts were sobering. We are spending Earth’s natural capital and putting such strain on ecosystems that their ability to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted. Some of the report’s key findings are as follows:

- About 60 percent (15 out of 24) of the ecosystem services identified in the report are being degraded or used unsustainably.

- There is established but incomplete evidence that the changes being made to ecosystems are increasing the likelihood of non-linear responses (i.e. accelerating, abrupt and potentially irreversible changes threatening human well-being).

- The harmful effects of ecosystem degradation are borne disproportionately by the poor and contribute to growing inequities and disparities.

Environmental degradation is already a significant barrier to achieving the Millennium Development Goals, a set of eight international development goals adopted by United Nations member states in 2000. Economic inequities are unsustainable for two reasons. First, they perpetuate poverty, which can lead to a vicious cycle involving increased degradation of environmental goods and services, which increases poverty, resulting in further degradation, and so on. Second, inequities hinder cooperation across different socio-economic classes, which will certainly be needed if we are to avert some of the more challenging problems involving common resources (e.g. freshwater, fisheries and the carbon-sequestering services of forests).

In addition to evaluating changes in the world’s so-called ecological balance sheet, the authors of the MEA reported the results of a scenario planning exercise intended to provide insight into likely futures. Drawing upon various political, economic, social and technological trends, they advanced four possible scenarios:

Global orchestration

The closest to ‘business as usual’, this scenario imagines a globally connected society focused on global trade and economic liberalization. Policymakers take a reactive approach to ecosystem problems. Economic growth is the highest, and population growth the lowest, in this scenario.

Order from strength

Sometimes referred to as the ‘Mad Max’ scenario for its bleak depiction of a regionalized and fragmented world, it is a future composed of primarily regional markets maintained through the use of military force. Little attention is paid to public goods like clean air, water and the like. Economic growth is the lowest and population growth the highest in this scenario.

Adapting mosaic

In the Adapting Mosaic scenario, regional watershed-scale ecosystems are the focus of political and economic activity. A proactive approach to ecosystem management is taken, resulting in greater resilience. This scenario is sometimes called the ‘small is beautiful’ scenario after economist E. F. Schumacher’s influential book advocating such a path. Economic growth rates are lower than in the other scenarios but increase over time, and population is nearly as high as in Order from Strength.

Technogarden

This scenario imagines a highly managed, technologically laden future that recognizes the value of ecosystem services and either invents substitutes (artificial trees!) or requires payment for the supply of ecosystem services. It reflects a globally connected world relying on sound environmental technology and achieves relatively high levels of economic growth and population growth in the mid-range of the various scenarios. This scenario is sometimes known as ‘Ecotopia’, after Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 utopian novel of the same name in which various earth-friendly technologies (e.g. homes made from extruded plant-based plastics) play important roles.

None of the MEA scenarios reflects a continuation of our present activities, although all are based on current conditions and trends. In some scenarios (e.g. Order from Strength), three of the four major categories of ecosystem services – provisioning services, regulating services and cultural services – experience declines. In others (e.g. Technogarden), some services show improvement (provisioning and regulating) while others (cultural) decline. Reversing the degradation of ecosystems in the face of increasing demand will require significant changes in policies, institutions and procedure, with a special emphasis on the identification and transfer of ecological benefits.

Well-established valuation systems and markets have existed for nature’s provisioning services (crops, livestock, timber) for millennia. Until recently, other ecosystem services have been largely ignored because they weren’t scarce and/or there were no markets for them. Coastal protection, climate regulation, soil formation and pollination services were just part of nature’s backdrop. Today, increasing population and increasing levels of resource scarcity have changed all that. We now live in a ‘full earth’ and need an economic framework for this situation. Conventional economic decision-making won’t work because many of our scarce environmental assets (e.g. clean air, soil retention) aren’t traded in markets. One solution is to bring them into the market (e.g., through taxes and subsidies), or through cap-and-trade schemes. This is the realm of environmental economics, and we are making progress on this front, although nowhere near fast enough. The Netherlands’ ‘tap water tax’ is an example of the former solution; the sulfur dioxide permit trading market authorized under the US Clean Air Act of 1990 exemplifies the latter.

Another approach is to recognize that we can’t easily establish markets for all types of environmental goods and adjust our economic thinking (e.g. along the lines of an ecological economics).1 Doing nothing is really not an attractive option. Because many of our environmental assets (oceanic fisheries, carbon sequestration services) are open access resources, inaction is likely to result in the tragedy of the commons – an unfortunate situation in which a resource is depleted because of individual, rational decisions. A key element in the valuation and establishment of markets for environmental amenities is the observation that many goods are public, rather than private goods.

This situation has been recognized by prominent economists in earlier times. The markets envisioned in Adam Smith’s seminal treatise, The Wealth of Nations (1776), were concerned primarily with the provision of private goods, though they were couched within a society with strong moral and social constraints. E. F. Schumacher, writing in Small is Beautiful (1973), observed the impact of declining ecosystem services in India, but his prescriptions were largely ignored in the West as not relevant and/or too exotic. Herman Daly, former senior economist at the World Bank, wrote about the challenges of economic growth on a finite planet.2 Although Daly was taken seriously, people did not really like the idea of uneconomic growth, or his suggested solution – a steady-state economics. In any event, valuation clearly lies at the heart of the problem.

Valuing nature

First of all, it is necessary to distinguish between value and prices. The aforementioned ecosystem services are clearly very valuable, but they are often unpriced. Adam Smith’s diamond-water paradox illustrates the difference: Water is clearly more valuable to human society than diamonds, yet the latter trades at a higher price. Why?

The answer lies in the respective supply and demand for the two commodities. Because the supply of water is large relative to demand (at least until recently), water carries a low price. The demand for diamonds is large (at least relative to supply), so they are high-priced. Economics is concerned about prices, because prices signal scarcity and provide incentives for trade. Prices reflect what a good or service is worth to a marginal buyer (i.e. the next buyer to walk through the door). Hence, value lies at the margin. Utilitarian philosophers – individuals subscribing to the belief that one should seek the greatest good for the greatest number of people – assert that a product’s or service’s value to society is the sum of its value to individual members, and that prices provide a good estimate for this value.

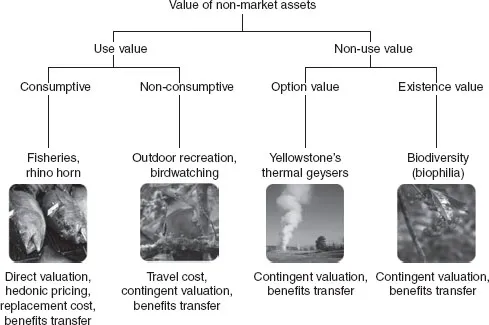

Alas, as we have noted, many ecosystem services are not traded in markets, and hence, no prices can be observed. Economists, still intent on evaluating trade-offs between scarce, marketable resources and until recently, not-so-scarce nonmarketable resources, have developed a number of techniques for estimating the value of non-marketed environmental assets. In so doing, they’ve identified several different categories of environmental value (Figure 1.2).

An environmental asset’s total economic value is the sum of its use value and non-use value. Use value refers to value derived from actual use of an environmental asset, while non-use or passive-use value refers to option and existence values. Use value, often broken down into consumptive and non-consumptive use value, is relatively straightforward. Examples of the former include drinking water, timber, wild game and recreational opportunities. Non-use values include many of the regulating and supportive ecosystem services. Option value arises from a willingness to pay for access to a particular environmental asset in the future and is based on uncertainties in future supplies, technologies and/or preferences. Existence value is the most controversial aspect of environmental valuation and refers to value placed on an environmental asset unrelated to any actual or potential use of the asset. Vicarious consumers of nature films or travel writing might ascribe existence value to particular ecosystems, as might societies who venerate specific natural sites for cultural or historic purposes.

Figure 1.2 Value of non-market assets

A complete description of methods for valuing the environment is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, the following section provides an introduction to five of the most prominent techniques identified at the bottom of Figure 1.2. Before going further, however, it is well to note three things. First, market prices reflect only small (marginal) changes in demand. This isn’t a problem when making decisions at the margin, but market prices can’t really capture the impact of large changes (e.g. the collapse of marine food webs from overfishing or a catastrophic decline in wild pollinators brought about by climatic changes). Second, there will always be some ecosystem services for which there are no markets, and thus estimates from these techniques are likely lower bounds on values. (Moreover, because prices rise as a good or service becomes scarcer, market prices generally underestimate total values). Finally, note that one goal of valuing environmental services is to provide owners with incentives to conserve them. Providing the right incentives is not necessarily t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Series Editor Preface

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I: Broader Contexts of Sustainable Development

- Part II: Germany’s Energy Revolution

- Part III: Transatlantic Cooperation at the Macro and Micro Levels

- Conclusion and Outlook

- Index