eBook - ePub

Europeanizing Civil Society

How the EU Shapes Civil Society Organizations

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Europeanizing Civil Society

How the EU Shapes Civil Society Organizations

About this book

The European Union clearly matters for Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). EU officials and European political entrepreneurs has been crucial in the promotion of funding and access opportunities, but they have been proven to have little capacity to use CSOs for their own purposes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Europeanizing Civil Society by Kenneth A. Loparo,Rosa Sanchez Salgado in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Europeanization of CSOs—Institutional Impact or Strategic Action?

Introduction

This chapter introduces a theoretical framework and a research design that broaden the notion of Europeanization to include a sociologically informed perspective. Drawing on previous literature on Europeanization, I propose a combination of institutional analysis with a micro-sociology of the European Union (EU). This combination will provide a better understanding of the impact of Europe on state–society relationships. The research design presented also addresses the challenges of this combination of approaches. It includes several levels of analysis as a starting point, the analysis of distinctive time periods and a comparative dimension. The last part of this chapter discusses and justifies the major methodological choices. The sociological comparative approach calls for a justification of the selection of the countries and policy fields under analysis. Detailed information on empirical data is also provided in the last section.

1 Europeanization studies, including a sociological dimension?

The catchy term ‘Europeanization’ has been employed in many different ways and for many different purposes. A victim of its own success, it can hardly be mentioned in any analysis without first discussing its many ambiguous and fluctuating meanings. But the absence of a common definition within the academic community does not necessarily make it useless. It rather offers a unique opportunity to clarify and develop our understanding of the impact of Europe. Few other terms in European studies have inspired so many efforts at definition and operationalization (Cowles et al. 2001; Featherstone and Radaelli 2003; Graziano and Vink 2007). The diversity of approaches is also an original contribution to the wider research design debate (Exadaktylos and Radaelli 2009; Haverland 2005). Given this diversity of views, Europeanization is hence considered ‘something to be explained’ (Radaelli 2006) rather than a theory to explain policy change at the domestic level. This section will discuss the shortcomings and advantages of the existing options, and it will be argued that the notion of Europeanization needs to be further developed to incorporate a sociological dimension.

1.1 Toward a sociologically informed concept of Europeanization?

The existing definitions of Europeanization cover a broad range of topics. Olsen (2002) has pointed out the many contrasting uses of this term. For example, it is used to describe changes in external territorial boundaries, the development of governance at the EU level, EU penetration in national and subnational systems of governance, the export of European forms of governance beyond the European territory and a political project aiming for a unified and politically strong Europe. Despite this variety, most efforts at conceptual clarification have considered Europeanization a device for capturing the impact of Europe (Börzel 2002; Closa 2001; Heritier et al. 2001; Schmidt 2004). Some of the most elaborate definitions also include processes of construction and the institutionalization of rules (Radaelli 2003) or the emergence of new modes of governance at the EU level (Cowles et al. 2001). The attempts to define Europeanization exclusively as uploading have not been very convincing. First, the process of transfer of competencies to the EU level is already satisfactorily covered by the concept of European integration. More importantly, studies defining Europeanization as uploading have not opted for a research design aimed at capturing uploading dynamics. Thus, there is an inconsistency between the definition of the term and the research designs that are later employed.

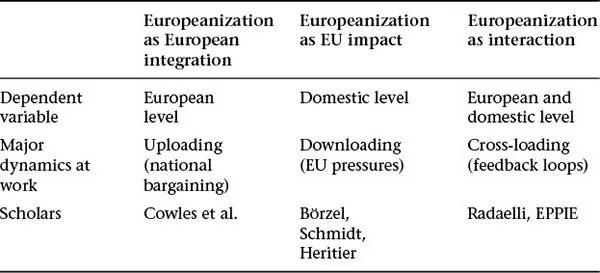

The two subsequent positions (presented in Table 1.1) reflect a trade-off between the analytical clarity of a given definition and its capacity to describe the complexity of the processes of change. Defining Europeanization exclusively as ‘downloading’ has the advantage of offering the most clear-cut approach to the term. This definition, in establishing a sharp separation between the process of European integration (uploading) and the process of Europeanization (downloading), preserves the analytical distinction between the dependent and the independent variables. The interrelation between European integration and Europeanization is acknowledged, but it is considered that uploading dynamics should not be covered by the definition for the sake of analytical clarity (Dyson and Goetz 2004).

Table 1.1 Different conceptualizations of Europeanization

Note: Expansions for acronysms used in the table are available in the list of abbreviations.

A few scholars have preferred a definition that accurately reflects the complexity of the dynamics at work. Europeanization is then defined as an interactive process in which dependent and independent variables cannot be clearly disentangled (EPPIE 2007; Radaelli 2003). This definition has the advantage of giving a broader picture, increasing the number of cases to be researched and uncovering the interactive character of the Europeanization process (for example, feedback loops). The definitions that place the emphasis on this interactive character highlight the explanatory variables of the process of change: institutions, strategic interests and shared beliefs (EPPIE 2007). This move has also the advantage of bringing European studies closer to mainstream comparative research (Hassenteufel and Surel 2000). However, the formulation of a research design that can capture uploading and downloading dynamics simultaneously is much more challenging. The conception of Europeanization as interaction is better adapted to capture the sociological dimension and thus is more appropriate for the study of civil society organizations (CSOs).

1.2 A stimulating disagreement on the most relevant explanatory factors

Studies that use the term ‘Europeanization’ have given weight to different variables, which has had significant effects on their research designs and on the scope of their findings. There is still an open and stimulating discussion on how different explanatory variables are to be connected and which ones should be considered the most relevant.

Scholars who conceive ‘Europeanization’ as downloading place greater emphasis on the significance of European institutions and rules as explanatory variables. This strand of research has developed into one of the most popular designs for the study of the impact of Europe, that is, the ‘goodness of fit’ model (Börzel and Risse 2003; Cowles et al. 2001). This model proposes an analysis in three stages: (1) the analysis of European norms and rules on the topic under study, (2) the assessment of the goodness of fit between European pressures and domestic practices and (3) the analysis of domestic mediating factors. Additional explanatory variables may be included in the research design, but only insofar as they are subsumed under the institutionalist framework. Thus, strategic interests and shared beliefs do not explain the transformation process itself; they only partially explain the final form it takes (Table 1.2).

As Europeanization is mainly concerned with the effects of European institutions and rules, it may seem reasonable that institutions are the most appropriate explanatory variable. The main assumption is that institutions are ‘collections of structures, rules and standard operating procedures that have a partly autonomous role in political life (March and Olsen 2005: 4)’. As may be expected, the weaknesses usually associated with institutionalism apply, such as the excessive role assigned to institutions in shaping human behavior and the ambiguity of the term ‘institution’ (Schneider and Aspinwall 2001).

The institutional approach to the impact of Europe has been increasingly challenged by scholars who place more emphasis on the domestic level. The institutionalist approach is considered too rigid and deterministic, and, most importantly, it may overlook domestic politics and the political dimension of change. The ‘goodness of fit’ argument, understood hitherto as a ‘theory that explains’ and not as ‘something to be explained’, is not only criticized for its lack of parsimony; it is even considered to be logically flawed (Mastenbroek and Kaeding 2006). According to this view, rational choice theory and sociological institutionalism should be taken as the point of departure of any analysis in this field. The significance of EU institutional pressures has also been challenged from the perspective of social movements studies. The emphasis is then placed on bottom-up dynamics and alternative explanatory variables such as resource mobilization theory or the role of ideology and framing (Beyers and Kerremans 2007; McCauley 2011).

Table 1.2 Europeanization and different explanatory variables

Top-down Europeanization | Challenging approaches | |

Major explanatory variable | Institutions | Political/strategic action |

Major level of analysis | European level | Domestic level |

Scholars | Cowles et al. | Mastenbroek and Kaeding Woll and Jacquot |

Last but not the least, the approach known as ‘the usages of Europe’ (Graziano et al. 2011; Woll and Jacquot 2009) focuses on domestic politics and political action. It proposes a more complex understanding of the combination of explanatory variables. ‘Usages of Europe’ are defined as ‘social practices that seize the European Union as a set of opportunities’ (Woll and Jacquot 2009: 116). Inspired by a sociology of the EU (Giraudon and Favell 2009; Saurugger 2008), these authors reject the mainstream methodological pattern that consists of isolating and confronting alternative explanatory variables. The sharp distinction between rational choice theory and constructivism is criticized, as well as the identification of sociological approaches with the constructivist turn in international relations. The distinction between shared beliefs and strategic action would be artificial at the micro level. However, more accurately reflecting the dynamics at work may often come at the expense of analytical clarity.

1.3 An unfortunate dissociation of levels of analysis

As Table 1.2 shows, the current positions do not only disagree on the relative significance of explanatory variables; they also place the emphasis on different levels of analysis. The dynamics of Europeanization concern the European and domestic levels simultaneously, but there is still a sharp disagreement on which level of governance is the most appropriate starting point for analysis. Studies that start from the European level tend to argue that the impact of Europe depends on the specific form of European governance (Andersen 2004; Bulmer and Radaelli 2004; Knill and Lehmkuhl 1999; Kohler-Koch and Eising 1999). A distinction is drawn between traditional hierarchical forms of governance, leading to the imposition of clear European rules and high levels of prescription and detail, and negative integration (or market-driven integration), in which the EU only alters the distribution of power and resources. The impact of Europe is also expected to differ when European pressures are produced by new forms of governance, which are based on coordination, flexibility, openness and interaction.

Whenever the European level is taken as the starting point, domestic institutions are seen only as mediating factors (Börzel and Risse 2003). The domestic level is subsumed to European politics, and thus domestic actors are only expected to adapt their political processes and policies to European practices and rules. Even if the emphasis is placed on EU processes, it is worth noticing that most current research acknowledges the great diversity of results of the Europeanization process (Radaelli 2003). For example, the wide range of responses to European pressures include processes of interpretation, editing and transposition (Mörth 2003).

Studies on the usages of Europe or on bottom-up Europeanization opt for research designs that take the domestic level as a starting point. They first track major changes at the national level and then try to assess the contribution of the EU. The main advantage of this research design is that it controls for other possible causes that may account for the policy changes under scrutiny and thus avoids bias toward EU-level explanations.

These studies’ attention is not directed to responses to European pressures but to how the EU is instrumentalized by domestic actors. Domestic actors use the EU to advance their own specific goals, to legitimate their political preferences, to gain support or to engage in blame avoidance or credit claiming strategies (Graziano et al. 2011). In this view, European rules and dispositions have no effects on their own; they only serve to accelerate, legitimate or obstruct certain domestic policy options (Palier et al. 2005). The motivations behind the different usages may be of different kinds: (1) logic of influence, in which actors try to shape the content of European policies; (2) logic of positioning, in which actors seek to improve their institutional position in the policy process; and (3) logic of justification, in which actors try to obtain support from other actors or the general public (Woll and Jacquot 2009: 117). This research design, taking a detour into the analysis of the impact of Europe, has uncovered interesting Europeanization mechanisms such as the leverage effect, which refers to the appropriation of European goals by domestic actors. The EU is considered therein as a selective amplifier rather than as the key driver of change.

1.4 Bridging divides in Europeanization studies between institutional analysis and a micro-sociology of the EU

As explained in the previous section (see also Table 1.3), research designs on the study of the impact of the EU differ along two dimensions: the level of analysis (Europe versus the domestic level) and the type of analysis (institutional analysis versus a micro-sociology of the EU). Both alternatives offer ample opportunities to include a wide range of explanatory variables in the analysis, such as the role of resources, ideology and framing processes.

Up until now, most research on Europeanization has placed emphasis on the top-left and the bottom-right quadrants of Table 1.3; while the other quadrants of the table are underdeveloped. The top-right quadrant draws attention to usages by Europe. ‘Usages by Europe’ refers to strategic action carried out by European policy officials to promote the dynamics of Europeanization. The bottom-left quadrant captures the possibility of horizontal Europeanization. This kind of Europeanization refers to all processes in which there is no pressure to conform to EU policy models (Radaelli 2003). Studies on the ‘usages of Europe’ have not yet directed attention to the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Boxes

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The Europeanization of CSOs—Institutional Impact or Strategic Action?

- Part I: Domestic Civil Society under EU Pressures

- Part II: Europeanizing CSOs through European Opportunities

- Part III: Europeanizing Civil Society through Participation

- Appendix 1: Interviews

- Notes

- References

- Index