eBook - ePub

The Invisible Hands of Political Parties in Presidential Elections: Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012

Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Invisible Hands of Political Parties in Presidential Elections: Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012

Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012

About this book

This book looks at networks of individual donors during early stages of presidential primary electons to determine party unity. It directly challenges the commonly-held perception that a "divisive" primary is a problem for the political party in the general election.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Invisible Hands of Political Parties in Presidential Elections: Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012 by A. Dowdle,S. Limbocker,S. Yang,K. Sebold,P. Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why Contested Primaries May Not Be Divisive Primaries

Abstract: This chapter begins by posing the question of why traditional measures of divisive primaries failed to predict the outcomes of recent presidential races. For example, the 2008 Republican process was one where John McCain was able to lock up his party’s nomination earlier than any modern contested nomination. By contrast, the Democratic contest dragged on into the summer months. However, when the general election arrived, Barack Obama was able to win handily. How do we account for this disparity? One overlooked element was the unity and enthusiasm gap between the two parties. We believe that traditional measures of intraparty divisions paint a misleading picture and suggest a more accurate measure to gauge party unity.

Dowdle, Andrew, Limbocker, Scott, Yang, Song, Sebold, Karen, and Stewart, Patrick A. The Invisible Hands of Political Parties in Presidential Elections: Party Activists and Political Aggregation from 2004 to 2012. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137318602.

Scholars have often claimed that parties undergoing hotly contested presidential nomination processes produce nominees who are less likely to win the general election in November.1 A political party does have a valid reason to fear the consequences of a divisive process that may split or demobilize its membership well after the nomination cycle has ended. In a first-past-the-post system, two political parties generally serve to aggregate individuals and groups with complementary interests into an electoral coalition.2 Winning elections has long been recognized as the primary purpose of these alliances.3 In the general election this aim is relatively easy to recognize as like interests are expected to aggregate into two opposing coalitions. However, deciding the party’s nominee often pits the interests contained within each of the political parties against each other as individuals and groups jockey for position within the party. While the candidate-centered system created by the McGovern–Fraser reforms of the early 1970s may be seen as exacerbating this problem, American history provides numerous examples of split conventions dooming a party’s prospects for winning the White House.

An obvious example of party dissention harming general election prospects can be found when a conflict produces a splinter party that runs against the party’s nominee. The Republican Party in 1912, where the progressive wing formed a splinter Bull Moose Party under Theodore Roosevelt, and the Democratic Party in 1968, where civil rights opponent and states right advocate Governor George Wallace of Alabama ran on the American Independent Party ticket, both provide excellent examples of this partisan division harming their party in the general election. Even if the dissent does not generate a splinter candidacy, party tensions can still weaken the general election nominee. This was the case in 1980 when incumbent president Jimmy Carter was hurt by a primary run by Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. In 1976, the Republican incumbent Gerald Ford also was challenged in his bid for re-nomination by Ronald Reagan, who had been the governor of California. Ford, like Carter, won his party’s nomination but failed in his re-election bid in November.

While logic and these historical examples may lead one to the conclusion that contested presidential primaries equal general election defeat, this is not a universal truth. The two nomination paths in 2008 diverge from this expectation and provide a powerful counter-argument to the conventional wisdom. The first path was the hotly contested Democratic nomination battle between Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama while the other race was quickly decided by the nomination of John McCain. We think of these elections as hotly contested because of the optics of campaign events. The question remains as to whether that means contested primaries always represent an expression of a party schism.

In order to examine this question we will need to move beyond the accepted wisdom and commonly used indicators to consider methods and measures that evaluate the behavior of the partisan electorate more precisely. Donors offer a base more broadly representative of the political party than the elite of elected officials but at the same time provide a more active, involved, and refined segment than the voting population at large. Furthermore, donor activity can be easily quantified, takes place using a consistent unit of analysis, is publicly reported, and individuals who opt in do so at an obvious expense to that person. Donor activity also has a specific advantage that elite endorsements and public opinion polls lack: the ability to easily select and equally support more than one alternative. Because past measures force the selection of only one individual, the measure artificially generates division where division may or may not be present. By creating a subset of donors, those that give to more than one candidate, we assert the absence or presence of division can be better evaluated.

The paradox of why “divided” presidential primaries do not always lead to disaster in November

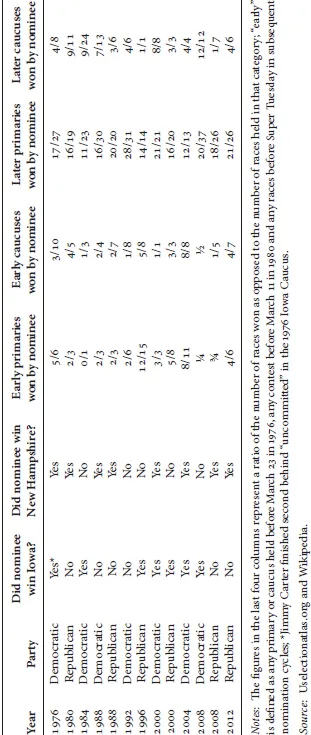

On the surface, the perceived negative relationship between hotly contested presidential primaries and general election success seems logical. First, in the most dramatic cases, losing candidates may run on a third party ticket or, minimally, may not encourage their followers to support the party’s nominee. Second, members of this losing coalition can leave the nomination process with sour feelings, making coalescence in the general election difficult. Third, the nominee’s attempt to placate losing candidates and groups may draw the ire of other elements within the party coalition, especially if accounts of these problems reach the general public through the news media. Finally, the longer a candidate remains in an electoral fight for the nomination, the more likely it is that the nominee will leave these primary contests battered and bruised with a sizeable quantity of the campaign war chest depleted. As the data in Table 1.1 demonstrate, most contested presidential primary contests during the past four decades have been intra-party struggles that have taken months to resolve.

Table 1.1 Contested primaries and caucuses in open nominations, 1976–2012

However, recent research has concluded that this hypothesis is not always accurate. Gurian, Cann and Snyder,4 for example, find mixed results with regard to 2008 Democratic Party nomination being a divisive process and questioned whether the extended contest had a negative impact on the party’s nominee during the general election. The question remains as to whether this was an aberrant byproduct of the unique and historic qualities of the 2008 candidate field or whether this disconnect between hotly contested nominations and general election partisan unity is endemic to the modern presidential nomination process. This book seeks to answer this question by looking at how parties coalesce during the presidential nomination process. We contend that political scientists and political pundits have fixated on how elements of a party are divided by the presidential nomination process. Instead, we propose the riddle of the disparate impact of “divisive” primaries can be solved by better understanding the state of unity within the party before the formal nomination process even begins. Observing the movement of support from one potential nominee to another allows for a greater understanding of whether support can be expected to return to the nominee in the general election. In reviewing the definition of a party as a coalition of complementary, but not necessarily identical, groups, we argue that such a view will lead us to a better understanding of how presidential nominations divide or unify the elements of the party. In a polarized environment, what may seem an internal squabble may actually presage the concerted mobilization of a group against its external opposition. For instance, studies of debates during the 1996 and 2000 Republican primaries showed that negative attacks by contending candidates hurt neither the aggressor nor the on-stage target; instead this competitive behavior actually boosted the audience’s post-debate assessment of all participants and the party itself. Underscoring this puzzling finding is that the audience actually had a more negative post-debate image of the party’s candidates choosing not to participate, and the members of the audience were also far more critical of the opposing party and its candidates.5

The nominations for both political parties in 2008 provide some anecdotal evidence to test our assertions. The 2008 presidential election was the first time in the United States since 1922 that neither political party had a sitting president or vice president as a potential candidate. Other historical elements gave weight to this election as the first viable non-white candidate and the first female aspirant to be a major contender comprised the top two choices of one major party. That said, in many ways 2008 was a typical election that followed many of the patterns observed in recent contests. Candidates still needed to raise money and win endorsements. Popular support still mattered as did the effect of debate performance and news coverage that altered that support. Finally, as has been the case in modern presidential elections, the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary came first with all candidates seeking to win the most delegates in every competition they entered. While organization and strategy led to success for one of the candidates in caucus states,6 the fundamentals of the nomination process by and large remained the same as other recent elections.

The 2008 Democratic Party nomination became a battle between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton lasting well into the summer months. Clinton, while starting as the front-runner, stumbled in Iowa but like many front-runners, managed to surge back in New Hampshire. Under the typical “rules” of the post-reform presidential nomination system, this win would have been enough for Clinton to swing momentum and ultimately the nomination back to her (as evidenced by Adkins and Dowdle’s account of George W. Bush’s 2000 Republican presidential bid).7 Obama, for his part, managed to withstand this electoral counterpunch and contest many of the subsequent primaries and caucuses. As the nomination battle lingered into the summer, Obama succeeded in winning the necessary majority of the delegates but still not the plurality of primary voters. On the surface, this would appear to be a highly contested primary within the Democratic Party. During spring and summer months many Clinton supporters vehemently stated that they would not support Obama during the general election. However, by November the vast majority had come to support the nominee of their party.8 This perplexing outcome seems to suggest that 2008 saw two viable contenders, either of whose nomination would have marked a historic choice for the Democratic Party, as acceptable alternatives for the Democratic electorate.9 Eventually the traditional groups forming the Democratic coalition returned to the party’s nominee, propelling Obama to the presidency.

By contrast, the Republican contest had concluded a number of months prior to their summer convention and the effective end of the Democratic contest. While John McCain clearly did not start as the front-runner, when voting began it became clear that he was going to have the easiest path to the nomination after his victory in New Hampshire. Fred Thompson entered the campaign only a few months before the start of the formal nomination season and formally exited in January of 2008. Rudy Giuliani, while enjoying initial fundraising success, was never able to convert that early money into actual votes. Mitt Romney bowed out after lackluster performances on Super Tuesday. Although he won Iowa and a few other contests, Mike Huckabee was unable to translate those successes into winning the nomination for the Republicans. Finally, the lingering candidacy of Ron Paul ended in early March, making John McCain the winner of the Republican nomination.

By comparison to the Democratic contest, this was a much less drawn out process. The Republican contest was effectively ended two months after the start of the Iowa caucuses. On the other hand the Democratic contest continued on for three additional months, ending on June 7. This date marks the latest a candidate clinched the nomination since Michael Dukakis in 1988. By contrast, the Republican contest concluded sooner than any...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Why Contested Primaries May Not Be Divisive Primaries

- 2 Refining (and Redefining) the Party

- 3 Multiple Donors and the Party as a Network

- 4 Multiple Donor Networks Begin to Shed Light on the Nomination Process: The 2004 Democratic Nomination Process53

- 5 A Tale of Two Networks: The 2008 Nomination Process

- 6 A Not-Romney Explanation: The 2012 Republican Nomination Process

- 7 Multiple Donors and Their Place in the Partisan Universe

- Appendix A: Geographic Patterns of Contributions to Presidential CampaignsThe Cases of the 2008 and 2012 Presidential Nominations

- Appendix B: Fundamentals in Social Network Analysis Theories and Methods

- Appendix C: Matrices of Shared Donors during Preprimaries

- Bibliography

- Index