- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores the use of mobile devices for teaching and learning language and literacies, investigating the ways in which these technologies open up new educational possibilities. Pegrum builds up a rich picture of contemporary mobile learning and outlines of likely future developments.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mobile Learning by M. Pegrum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Mobile Landscape

The years 2002 and 2013 stand out in the history of international telecommunications. In 2002, the number of mobile telephone subscriptions surpassed the number of fixed lines globally; and in 2013, the number of internet-enabled mobile devices is set to surpass the number of desktop and laptop computers (The Economist, 2012; Meeker, 2012). Welcome to the mobile age.

As of early 2013, mobile phone penetration was estimated at 96% globally and 128% in developed countries (ITU, 2013), reflecting individuals’ ownership of more than one phone. There are already over a billion smartphone subscriptions and the penetration of tablets is growing rapidly, with media players and other handheld devices widely, if not evenly, distributed. There is also a strong trend towards ownership of multiple mobile device types, with 25% of mobile users expected to own a second device by 2016 (Cisco, 2012). This brings added mobility and flexibility, as users move seamlessly between fixed and mobile screens.

In the developing world, where mobile penetration is estimated to have already reached 89% (ITU, 2013), the proliferation of mobile devices may permit a leapfrogging of the desktop and laptop stages typical of developed countries. This doesn’t mean that 89% of the population has phones, since the figures refer to subscriptions, not people, but it’s true that large numbers of people are prepared to outlay a significant proportion of their income – estimated at 4–8% of average monthly income in India and Sri Lanka, for example (Deriquito & Domingo, 2012) – to own mobile phones. Access rates in developing countries are further bolstered by the common practice of sharing phones between family members and friends (GSMA, 2010a). Many of these devices, which often represent users’ first gateway to the digital world, are basic or feature phones which operate on older second generation (2G) networks. Yet trends are shifting: in February 2013, China surpassed the USA with the largest number of active smartphones and tablets in the world, but in terms of growth it was placed only sixth, following Colombia, Vietnam, Turkey, the Ukraine and Egypt (Farago, 2013).

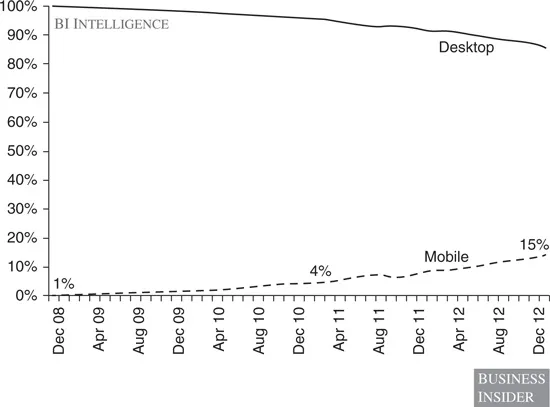

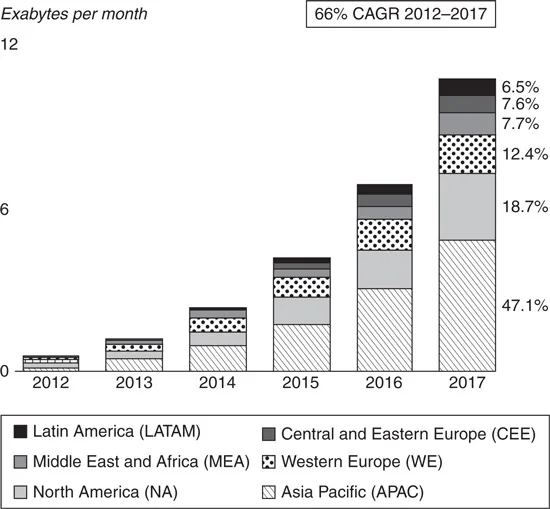

Globally, mobile traffic reached 15% of all internet traffic by the end of 2012 (see Figure 1.1) and is on track to surpass 25% in 2013/2014 (Cocotas, 2013; Meeker & Wu, 2013), accompanied by a corresponding decline in desktop and laptop traffic. This phenomenon isn’t restricted to the developed world. Indeed, in 2012, mobile traffic in India, soon to be the world’s second largest internet market, exceeded fixed internet traffic (Meeker, 2012). Worldwide, large increases in mobile traffic are predicted through to 2017 and beyond, with the Asia–Pacific region coming to dominate in the near future (see Figure 1.2).

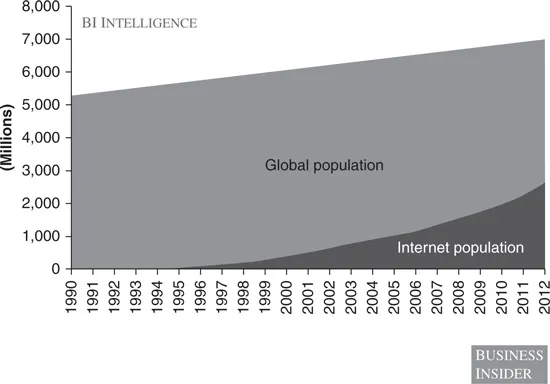

It’s not just our devices which are mobile; more and more, so are we. We can socialise, learn and work across multiple real-world settings. After centuries of growing immobilisation of the populace, which gradually became tethered to homes, schools and workplaces, we’re seeing the rise of what The Economist calls ‘the new nomadism’ (Woodill, 2011: Kindle location 127). Thanks to mobile devices and their constant connectivity we can access information and resources, connect to and communicate with others, and create and share media almost anywhere. While devices and connections in the developed world far surpass those in the developing world in both quantity and quality, more and more of the world is coming online (see Figure 1.3), and more and more of the newest users are accessing the internet predominantly or solely through mobile devices.

Figure 1.1 Global desktop vs mobile traffic 2008–2012. © Business Insider Intelligence, https://intelligence.businessinsider.com, reproduced by permission.

Figure 1.2 Global mobile data traffic by region 2012–2017 (forecast). © Cisco VNI Global Mobile Data Forecast 2012–2017, reproduced by permission.

In the desktop era, the internet seemed like a separate place partitioned off from everyday life by monitor screens. Mobile devices, especially our multiplying smart devices, integrate the virtual and the real as we carry the net with us, entertaining and informing ourselves and sharing our thoughts and experiences while we navigate through our daily lives. Mobile devices also represent a return to embodiment, augmenting our brains and our senses as we interact with the world around us. For now, we keep them close to our bodies, waiting for the day when they’ll migrate into our clothing and, eventually, under our skin. No longer will we enter cyberspace; cyberspace will enter us. With developed countries setting the pace, but developing countries acting as catalysts for innovations appropriate to their own contexts, we’re in for some dramatic changes to our sense of space and time, our understanding of ourselves and others, and our ways of learning.

Figure 1.3 Global internet population 1990–2012. © Business Insider Intelligence, https://intelligence.businessinsider.com, reproduced by permission.

From e-learning to m-learning

The field of e-learning (electronic learning) is well-established. There’s a whole area of scholarship built around the educational use of digital technologies like desktop and laptop computers, the web, and especially web 2.0. M-learning (mobile learning) shares enough common ground with e-learning that it features regularly in major e-learning conferences, journals and books. Yet we’ve also seen the emergence of dedicated conferences like mLearn (since 2002), International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) Mobile Learning (since 2005) and MobiLearn Asia (since 2012); a professional organisation, the International Association for Mobile Learning (IAmLearn) (since 2007); journals like the International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation (since 2007) and the International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning (since 2009); and growing numbers of book-length treatments. Of course, the very form of the term ‘m-learning’ can’t help but suggest parallels with ‘e-learning’ at the same time as it suggests there may be specific differences. Other recently popular terms like ‘u-learning’ (ubiquitous learning) and even ‘p-learning’ (pervasive learning) hint at the same kind of blend of commonalities and differences.

Similarly, the field of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) is a well-established subfield of e-learning, with its oddly old-fashioned moniker having seen off all challengers to gain global acceptance. In recent years, mainstream CALL conferences, journals and books have increasingly included mobile technologies in their purview, suggesting that in the language teaching community there’s a general perception of continuity between the use of fixed and mobile tools. But perhaps the sense of continuity is most neatly captured in the term Mobile-Assisted Language Learning (MALL). In the wake of George Chinnery’s well-known 2006 article ‘Going to the MALL’, which brought the acronym to the attention of many teachers, it has continued to gain traction, surfacing at conferences, in journals and in books. As with ‘m-learning’, the form of the term ‘MALL’ suggests there may be both commonalities and differences with ‘CALL’.

We’ve already noted that there are key differences between fixed technologies, which tend to be separate from daily life, and mobile technologies, which tend to be part of it. To decide how large the differences are, and how significant they are for education, we need to take a closer look at mobile devices. But this is a somewhat contested category. As a rule of thumb for differentiating what is mobile (which is included) from what is portable (which is not), we might use Puentedura’s (2012) distinction that portable devices are normally used at Point A, closed down, and opened up again at Point B, while mobile devices may be used at Point A, Point B and everywhere in between, without stopping. While leaving a fuller discussion until Chapter 3, it’s worth noting that laptops, with the exception of smaller devices like XOs, are not normally included. A representative list might include mobile phones, whether feature phones or smartphones, along with tablets, digital media players, e-readers and handheld gaming consoles.

A key theme of the recent m-learning literature has been that mobility does not refer only, or even primarily, to devices, but to learners (Pachler et al., 2010; Woodill, 2011) and even to learning itself (Traxler, 2007). Some suggest that it may also apply to the wider society and era in which the learning is taking place (Sharples et al., 2010; Traxler, 2007). Yet it’s not easy to tease apart the mobility of the devices, the learners, the learning, the society and the era. Moreover, any definition of m-learning which doesn’t view the devices as central risks straying into nebulous claims that all learning has always been mobile. While it’s true that in some senses toys or books are mobile learning tools, such discussions go well beyond the scope of this book. Therefore, while bearing in mind that device mobility is not the be-all and end-all of mobile learning, taking a look at the affordances of the devices themselves is a logical way to begin unpacking the interlocking elements of mobility which underpin m-learning.

From affordability to affordances

In the discourses around digital technologies, we hear a great deal about the affordances of mobile devices, in terms of their social and educational impact and even, beyond this, their economic and political impact. But we must remember that affordability precedes affordances.

In the developed world, it’s the affordability of mobile devices that has encouraged their spread throughout the population. This is why we’re now in a position to discuss the social and educational affordances of smart devices, with their third generation (3G) or fourth generation (4G) connectivity and their smorgasbord of apps. On the other hand, it’s easy to forget that lack of affordability remains an issue, leading to a patchy uptake of the iPods, iPhones and iPads that we hear so much about – along with other similar devices – and introducing equity challenges in Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) models.

But it’s in the developing world that affordability matters most. As hardware prices continue to fall, a ‘ “mobile first” development trajectory’ is becoming evident (World Bank, 2012, p.3). Africa has the world’s highest growth rate in mobile phones (Isaacs, 2012a), which are described by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) as the ‘mass ICT technology of choice for Africa’ (cited in ibid., p.12). In Latin America, meanwhile, there were an estimated 17 computers per 100 people in 2011, but there was already almost one mobile phone per person (Lugo & Schurmann, 2012). The limited affordability of desktop and laptop computers, along with the limited affordability and coverage of fixed telecommunications infrastructure, means that mobile devices are often the best, or only, option for internet access in the developing world (Deloitte/GSMA, 2012). This is borne out by statistics: although mobile devices accounted for 15% of global net traffic by the end of 2012 (see Figure 1.1), some 58% of web traffic was already mobile-based in Nigeria and Zimbabwe in that year (Deloitte/GSMA, 2012).

But affordability is relative. While an average European spends a little over 1% of their monthly income on mobile communication, an average African spends 17% (STT & Grosskurth, cited in Vosloo, 2012). What’s more, the average African gets a lot less for their money. The low-end phones typical of the developing world, with their limited functionality and connectivity, offer far fewer of the affordances we hear about in the developed world. By the end of 2011, 90% of the world’s population was covered by 2G networks, but only 45% by 3G networks (ITU, 2012). In 2012, nearly 90% of mobile subscriptions in Africa were still restricted to older 2G or 2.5G networks (Gallen, 2012). We need to remember these limitations in projects that seek to broaden access to educational opportunities. Although it makes sense to plan with an eye to future mobile expansion in developing regions, our planning must remain grounded in the – long – present.

Of course, even when their affordability reaches a level that allows them to become widespread, new technologies don’t lead to social changes by themselves (the technological determinism fallacy); nor can we say that social changes alone have led to the rise of new technologies (the social determinism fallacy). Rather, society and technology influence each other, a view often called a social shaping perspective (Baym, 2010; Selwyn, 2013; Williams & Edge, 1996). The social context promotes certain lines of technological development and certain uses of technologies; the technological context amplifies some social practices and constrains or undermines others. The obvious uses of new technologies, seen within a larger social framework, are what we might term their affordances – put simply, the purposes to which they seem most easily to lend themselves.

It’s possible to identify certain affordances of mobile technologies which are bound up in the social and educational changes we see happening around us. Leaving aside for the moment the question of affordability, to which we’ll return later, it’s time to take a look at these affordances.

Where the local meets the global

In discussions of digital technologies, we often hear about an increased emphasis on the global but, especially since the advent of mobile phones, we’ve also heard about the increased salience of the local. While these points might at first seem contradictory, they’re tightly intertwined with each other and with the ongoing transformation of our sense of space and place. Interestingly, the term ‘m-learning’ is sometimes seen as placing emphasis on mobility, seamlessness and the ‘global’, while the term ‘u-learning’, with which it’s occasionally interchanged, may be seen as placing emphasis on contextualisation and embeddedness (Leone & Leo, 2011; Milrad et al., 2013) and thus the ‘local’. But ultimately these are two sides of the same coin.

We’ve become used to accessing digital materials, digital communications and digital networks from whatever real-world locations we find ourselves in. As the developed world in particular shifts increasingly towards a digitally mediated network society structure (Castells, 2010) – predicated on mobile networked individualism (Rainie & Wellman, 2012) – our online and offline lives overlap more and more. Our mobile devices contribute considerably to the fact that we find ourselves living simultaneously in a local space of places and a global space of flows (Castells, 2010; Castells et al., 2007). In other words, we live in local real-world contexts and at the same time in online networks, which provide a permanent, pervasive, global context for our thoughts and actions. As Manuel Castells (2008) writes of our era of mobile communication: ‘We never quit the networks, and the networks never quit us; this is the real coming of age of the network society’ (p.448).

Some m-learning focuses on global materials, communications and networks, and ignores the local context. As a result, the physical setting may be irrelevant to the substance of the learning (if not to its organisational, psychological or affective aspects). Connectivity permitting and distractions notwithstanding, it’s possible to learn anywhere: in a school, a café, a park or a train. This kind of seamless learning (Chan et al., 2006; Looi et al., 2010) across different physical spaces is a more flexible version of e-learning, untethered from desktop computers. Some educational institutions are already exploiting this flexibility by reconfiguring the traditional ‘built pedagogy’ (Monahan, 2002) of classrooms, making them into adaptable spaces which teachers or students can reshape to suit newer pedagogies and interactions mediated by mobile devices.

But m-learning may equally entail a heightened focus on context. In the past, a contextual focus was present in limited ways in excursions and field trips. Now, education can emerge much...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. The Mobile Landscape

- 2. Agendas for Mobile Learning

- 3. The Technological Ecosystem

- 4. How to Teach Language with Mobile Devices

- 5. What Language to Teach with Mobile Devices

- 6. Teaching Literacy/ies with Mobile Devices

- 7. Preparing for a Mobile Educational Future

- Recommended Reading

- References

- Index