- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Business of News in England, 1760–1820

About this book

The Business of News in England, 1760-1820 explores the commerce of the English press during a critical period of press politicization, as the nation confronted foreign wars and revolutions that disrupted domestic governance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Business of News in England, 1760–1820 by Victoria E. M. Gardner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The English Press

Eighteenth-century newspapers, comprising single sheets of paper folded once and printed with time-sensitive information (‘news’) and advertising on both sides, contributed to a new understanding of their readers’ worlds. Published with metronomic regularity, carried by wagon, by post and on horseback across regions and nations, by newsboy and hawker crying through the streets, they spread news, ideas, opinions and fashions. Newspapers connected their readers to one another locally and in geographically disparate towns, villages and regions, encouraging new dimensions of national and imperial belonging, new conceptions of time and space.1 They connected politicians and public, fostering a new accountability of parliament in Westminster to the nation and offered a means by which intensely local politics could interact with national concerns.2 Yet newspapers were more complex, in cause and effect. The press’s capacity to bring people together also created divisions, for newspapers shone inwards light on regional identities and differences, and highlighted the uniqueness of individual communities.3 They were politically opposed. They heightened class differences, physically in their prohibitive cost and in content that underlined the differences in middle-class mores from those above and below. In the later eighteenth century, this power both to unite, intensify and divide made newspapers attractive but also dangerous. This chapter explores how press and state negotiated between them and how provincial newspapers particularly shaped the press-politics landscape.

The operation of the newspaper press depended on a set of negotiations between state and newspaper trade, the latter of which consisted of owners, editors and agents who established, produced, managed and sold newspapers. Many of these men and women were invested in local politics and most were interested in making a profit. As information was relayed through the press, these mediators had the power to amplify and change messages. Successive administrations were aware of the growing power of the press in reaching the political nation and its potential to shape public views, as well as its sizeable contribution to the national coffers in the form of duties. Politicians also had to take account of the notion of public opinion as an agent in the political process, which gained pace over the eighteenth century. After the mid-century, through the Wilkes affair and the American and French Revolutions, the liberty of the press was associated with historic English freedoms and became a key element in the ‘alternative structure of politics’.4 This was buttressed by the Enlightenment response to news, in that print made knowledge.5 All of this was reinforced by the press’s commercial success, with advertising revenues freeing many newspapers from political subsidies.6 Yet this could only ever affect individual titles rather than the press as a whole. Moreover, as later chapters demonstrate, there were other means of social and economic control enforced by politicians and advertisers.

In national terms, the power of the press developed thanks to the level of finance that newspapers placed collectively into the national coffers and the cohesiveness of members of the press as a group. This further gave the provincial press, so often viewed as the junior partner of the English press, leverage within national debates on the press. Rather than the evolution of the press-politics nexus being the result of a battle between an ancien regime that continued to suppress it on the one hand, and bourgeois individualists who freed the press through commerce on the other, long-term attitudes were shaped by political economy.7 This involved liaising and negotiating with the ‘respectable press’ while tightening laws and prosecution instruments to isolate or neutralise problem papers. The result was a paradoxically closer relationship between parliament and the respectable press, comprising both metropolitan and provincial papers, but a divergence between metropolitan and provincial newspaper presses as each battled for priority in legislative decisions. Newspapers did not simply play a role within the ‘alternative structure of politics’ but came to bridge the divide between it and parliament.8

Eschewing earlier characterisations of the provincial press as parasitic and worthless, historians now recognise the importance of provincial newspapers as effecting and reflecting distinctive regional ideas and opinions.9 Provincial newspapers have even been situated alongside metropolitan titles as barometers of eighteenth-century national opinion.10 Examining metropolitan and provincial newspapers together reflects, on the one hand, the way in which the English press was treated equally in law, regardless of geographical location. On the other, it disregards the ways in which the two presses were interlinked and in which their relationship affected both the internal dynamics of the press and the balance of power between press and politics. Moreover, it implies that differences between London and provincial towns were slight, an inference that contemporaries and historians alike would readily reject. Comparing the simultaneously interlinked and purposely separate London and provincial presses within the same analytical frame and tracing their responses to legislative and fiscal change, this chapter demonstrates that the provincial press played a central role in the English press and provided considerable firepower within the press–politics nexus. In doing so, it demonstrates that competition with the London press powered the emergence of the provincial press as an independent force within English politics.

The chapter is divided into five sections. The first introduces the provincial press, establishing the emergence of the press in the light of the lapse of the Licensing Act and subsequent stamp acts and tracing its national expansion over the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The second section determines the differences between London and provincial newspapers, demonstrating that the provincial press had a unique role in news delivery, in part shaped by competition with the London press. This was exacerbated by the construction of new roads and an integrated postal service, discussed in the third section, which introduced greater competition from the London papers within provincial towns and propelled change in delivery and content. Similarly, as the fourth section demonstrates, legislative change in the form of the rise of parliamentary reporting encouraged new region-specific content and encouraged greater accountability on the part of regional politicians. The final section focuses on finance. It demonstrates that provincial newspapers made the largest contribution in advertising duties paid to the government. This gave the provincial press unique leverage within government discussions on the most effective means of taxing the press. Ultimately, the prominence of the provincial press in these discussions indicates recognition by politicians and legislators as to its power in fiscal terms and as a watch on politicians.

Press and nation

The eighteenth-century press was characterised by the constant tension between it and parliament as the former sought greater freedoms and the latter approached the freedom of information with caution. The lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695 precipitated the establishment of the newspaper press in England. The Act had expired before, between 1679 and 1685, provoking an outpouring of news-sheets and newspapers. However, the period after 1695 was unique, not simply for the lapse’s eventual (and for the most part unanticipated) permanence but in the establishment of a national press, for printing was permitted for the first time outside of London, York and the University towns. In 1702 the first provincial newspaper (either the Bristol Post Boy or Norwich Post) was issued.11

Licensing was not abandoned altogether, and in 1712 stamp and advertising duties were placed on every individual copy of a newspaper and every advertisement in a single issue. This brought in funds vital for overseas campaigns, starting with the War of Spanish Succession and escalating over the later eighteenth century in a period of almost constant warfare. It also had the not-unintended side-effect of limiting purchase to the middling ranks and above, that is, to the respectable nation.12 Stamp duty on newspapers was introduced in 1712 at ½ d. per copy per issue and was increased in 1757, 1776, 1789, 1797 and 1815, in which year it reached 4d. Advertisement duty was also brought in in 1712, starting at 1s. per advertisement per issue and increased in 1757, 1780, 1789 and 1815, when it reached 3s. 6d. The average newspaper therefore cost 2 ½ d. in 1757 and 7d. after the 1815 Stamp Act.13 This affected readers and proprietors. In terms of readers, each single copy of a paper was subject to stamp duty, meaning that those who could afford provincial newspapers were thus middling sorts and above with the requisite disposable income and literacy. Even so, as this chapter later explores, news could be absorbed in myriad ways that did not require purchase and news was accessible to artisans, labourers and others. In terms of production, stamped paper alone cost more than an entire printing office’s weekly wage bill, which forced an almost immediate dependence on advertising income. Profit could be made here because printers could charge advertisers a higher rate than advertising duty alone. This also meant that for printers, barriers to entry were high because they involved considerable and immediate outlay. Far from limiting the press’s freedom, however, this was advantageous for it limited competition and enabled some titles to become wealthy thanks to advertising.14 More than this, high tax contributions also gave the press leverage in parliament, as this chapter will examine later.

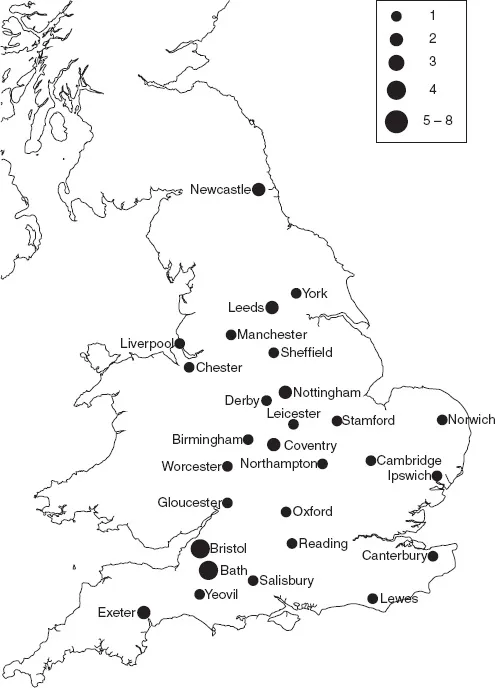

Over the later eighteenth century the number of provincial newspapers increased significantly thanks to demographic and urban change, developments in national politics (especially the rise of contested elections) and, with newspaper profits dependent on advertising, consumer spending. By 1760, as Map 1.1 shows, there were 35 provincial titles. Newspapers were established in main towns on the roads to London and serving large regional hinterlands that could support requisite readership and advertising, particularly regional and county capitals such as Northampton, Exeter and Gloucester, large market towns, such as Sherborne, and port towns including Liverpool and Newcastle. Most early newspapers were connected to a printing house and established in order to connect with a regional market through a newspaper’s distribution system and the number of printing houses increased significantly. By the mid-1740s, 174 towns in England had 381 printers, booksellers and engravers.15 Around 1760, most provincial newspapers also professed political impartiality in order not to alienate readers and town councils although in those towns with vibrant local politics, such as Bristol and Newcastle, newspapers were partisan, not least to differentiate themselves from each other.16 Indeed, by the 1760s and the Wilkes affair, ‘public opinion’ and the ‘liberty of the press’ were terms that were increasingly commonplace among press and public.

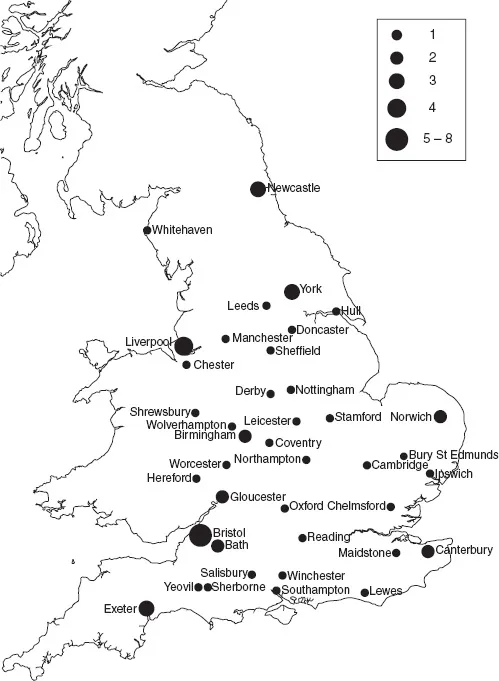

By 1790 there were 60 provincial newspapers. Competition and the growth of provincial towns also meant that newspapers had moved into smaller towns, such as Maidstone, and colonised national borders, as shown in Map 1.2. The Newcastle and Whitehaven papers served the Scottish borders, competing with those from Edinburgh and Glasgow. To the West, several titles, including the Hereford Journal, were ‘happily situated for immediate communication with a considerable part of Wales’ which was without an English language newspaper until 1804.17 Competition also meant that circulations were shrinking, although some newspapers dealt with this through syndication; as early as 1775, an edition of Brice’s Exeter Journal was published in Plymouth.18 Industrialising towns were also gaining a growing number of titles as they expanded, so that Manchester and Leeds had two apiece. The Atlantic ports of Liverpool and Bristol laid claim to three titles. Newspapers required readers and advertisers in order to sustain them but local and national politics motivated significant changes in the newspaper press, especially during the American and French Revolutions. Groups and individuals used the press both to promote extension of the franchise and parliamentary reform and to defend the existing status quo. At the same time, freedom to publish parliamentary debates from 1771 encouraged greater legislative transparency, encouraging the press to take on the role of watchdog, and greater collaboration with the press as mediators between parliament and the people.

Map 1.1 Geographical distribution of provincial newspapers, end 1760

Map 1.2 Geographical distribution of provincial newspapers, end 1790

Radical newspapers were a numerically small but important feature of the provincial newspaper landscape in 1790, the product of a continuing tradition of oppositionist print politics over much of the eighteenth century. In total, at least eleven provincial radical titles calling for urgent parliamentary reform were established in the 1780s and 1790s, most of which were scattered in the Midlands and the North, including Wolverhampton, Manchester, Newcastle and Leicester. They combined local grievances with national calls for parliamentary reform. The Chester Chronicle, for example, was purchased in 1783 in order to lend support to the town’s Independent interest there and the Sheffield Register was establ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 The English Press

- 2 Advertisements, Agents and Exchange

- 3 Provincial Newspaper Proprietors

- 4 Securing the Family, Embedding the Trade

- 5 Communities and Communications Brokers

- 6 News Networks

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index