- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book adopts an explicitly postmodernist perspective of the digital revolution. While exploring issues relating to the re-creation of social life in the digital world, its main focus is on the political economy and in particular the extent to which the paradigms of capitalism and socialism can be mapped as postcapitalism onto this new world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Digital Evolution in Postmodernity

Abstract: Instead of the binary division between capitalism and socialism or between modernism and postmodernism, there is a way to distill the best (most efficient and socially beneficial) that these binaries can offer so as to find a pragmatic middle-ground. Digital technologies don’t align more strongly with one side of the binaries, but offer a way to realize and test some elements of both of them. In doing so, an evolutionary trajectory is outlined so as to acknowledge the continuity rather than revolutionary nature of the Digital Age.

Sassower, Raphael. Digital Exposure: Postmodern Postcapitalism. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

DOI: 10.1057/9781137312402.

DOI: 10.1057/9781137312402.

I Beyond binary oppositions

In order to examine the potential of a multilayered approach to the Digital Age in the postmodern world whose postcapitalist marketplace encourages participation and prosperity, we should break down some conceptual barriers that stand in the way of clear thinking. Among them is a complacent confinement to traditional binaries, such as modernism and postmodernism, capitalism and socialism, and technoscience and the humanities. Each binary has its justification for drawing distinctions so as to classify some ways of thinking as modern as opposed to postmodern, or ways of conducting business as capitalists rather than as socialists. Though radically different, such binaries entrench differences among ways of thinking rather than seeing all proposals as fluid and open-ended and amenable to change when changing circumstances demand a change in approach.

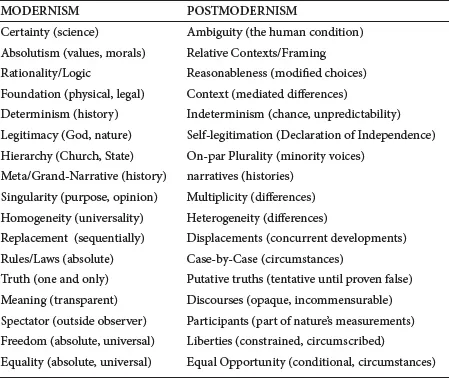

The postmodern condition, so eloquently outlined by Jean-François Lyotard (1984), has been with us all along and therefore any sense of historical sequencing (modern→postmodern) misses the point of the postmodern condition. Lyotard explains the power relationship of modernity and capitalism colliding for universal hegemony. One way to illustrate the parallel, yet different, modes of thinking that distinguish modernism from postmodernism can be seen in Table 1.1 below. Note that at times the two columns complement each other (both and) while at others they are oppositional if not outright contradictory (either or).

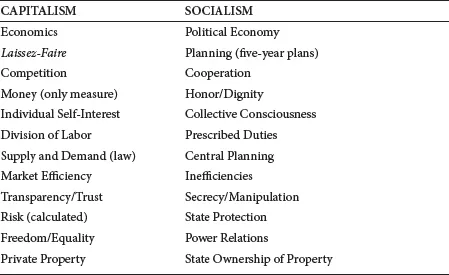

Table 1.1, which is two-columned, attempts to capture the differences that inform the two ways of thinking in the most general manner and without any pretense of comprehensiveness. Yet, it illustrates the kind of conceptual reference-points worthy of examination (see an alternative in Hassan 1987). To some extent, we all live in both “camps” or inadvertently participate in or make use of these two ways of thinking, depending what we are dealing with. In the Digital Age, a recognition of these intertwined mind-sets may assist us in figuring out why we seem confused when computer engineers are closed-minded in one sense (within their code) and open-minded in another (sharing their work with others free of charge). The postmodern condition finds allies in every technological age, from experiments during the Industrial Revolution to contemporary attempts at reconfiguring intellectual property rights (see Berry 2008, Boyle 2008). If we layer these two mind-sets and practices with those of political economy (capitalism and socialism, as in Table 1.2), we can more fully appreciate the complexity on one hand and the complete unpredictability on the other of this new emerging age of digital technologies.

Table 1.1 The Postmodern Condition

Table 1.2 Capitalism and Socialism

With the outlines of what capitalism and socialism ought to look like in their ideal states, we should continue to speculate about their potential for sustainable durability and success. Capitalism has traditionally been couched within a legal system that protected certain rights and activities through tax legislation, such as deduction for investments and losses, or through the courts to enforce contracts. As seen most recently in the US, “too big to fail” has been a mantra that justified the use of enormous public funds to help prop commercial and investment banks alike whose bad decisions would have brought them to bankruptcy. The European Union is likewise saddled with national capitalist markets and social programs that require intervention and subsidies unknown to the drafters of ideal capitalist markets. The same judgment is appropriate in the case of socialism, since the best we have seen in the past one hundred years are cruel examples of state communism (USSR, China, and many others) that deliberately overlooked the humanistic foundations of ideal socialism where overall abundance (post-capitalist wealth accumulation) would indeed cater to everyone’s needs and everyone would eagerly contribute to the general welfare of all.

Absent these idealized states, a compromised political economy has presented itself. Under these practical circumstances we are witnessing mixed-economies where welfare commitments are available but resented, or where a central authority dictates business practices. The notion of postcapitalism, as we shall see in more detail later, therefore is neither alien nor worrisome, but rather a more formalized restatement of trends that we should endorse, promoting the best both capitalism and socialism offer in their pristine versions. It seems that the confusion of contemporary digital culture when fishing for ideas that have in fact been there all along is that in doing so it is unprincipled. But that is exactly what is at stake: postmodern postcapitalism, a hybrid mode of being that celebrates the best it finds without regard to traditional boundary conditions or outdated restrictions. Yet, amidst this celebration it’s only fitting to acknowledge a troubled history that we have to overcome in the Digital Age, the dividing lines between technoscientists and humanists.

II Beyond any two cultures

Though the horrors of the twentieth century are behind us – world wars, atomic bombs, genocides – their residues still affect our thinking. One of them is the troubling distance between the humanities and the sciences, what C. P. Snow famously called the “two cultures.” Can digital technologies ameliorate this concern? And if they do, when artists and computer scientists collaborate on video games, does this collaboration indeed bridge their training and conceptual divide? According to I. I. Rabi (1970), one way to bridge the divide is not simply to find common intellectual grounds or practical reasons, such as the politics of the Cold War of yesteryear or video games today, but through an affirmation of human wisdom. Human wisdom commands us to make use of whatever intellectual knowledge we can gather from every available resource and test it against our experiences to produce effective and life-saving policies. Common educational structures should be in place to accommodate this process, whether understood in the pragmatic tradition of the American John Dewey or in the more abstract sense of the March of Reason as propounded in the nineteenth century by the German philosopher Hegel. The goal, however achieved, is to bridge the intellectual and socioeconomic gaps that have become evident by the middle of the past century (in an age of expertise, Sassower 1993) to ensure the survival and prosperity of the human race.

Some of the concerns related to the two cultures remain intact: the technical prowess of scientists and engineers in the Digital Age seems magical even in the eyes of literary intellectuals who use digital gadgets. But while the “cultures” discussed in the past century were privileged insofar as they embodied the intellectual and aristocratic classes of the UK, the cultures we observe in twenty-first century America are much more bifurcated. We have the educated and the less educated cultures (in terms of postsecondary education), and within each one of these we have distinctions associated with literacy and expertise (cutting-edge digital technologies) and areas of work and thought (from entertainment to politics). Would Snow or any of his contemporaries associate television-literate audiences with what he perceived to be “literary intellectuals”? For him, intellectuals were academically educated and at times employed within the academy; some were interested in literature and some in the sciences. He was struck by the fact that they actually had much more in common than they themselves would admit, and it’s exactly that fact he wanted to exploit to bridge the widening gap between the sciences and the humanities.

What seemed a reasonable expectation in the past century may seem ludicrous in this one, when the gap between the rich and the poor is ever-increasing, when higher education funding is undermined in part because of the poor economic conditions of many states that traditionally subsidized their namesake universities (for example, the state of Colorado provides less than 5 percent of the annual budget of the University of Colorado system), and when the overall anti-intellectualism of the nation, as Richard Hofstadter illustrated (1966), keeps rearing its ugly head. It’s not only that the so-called two cultures are in fact ten or twenty different cultures (science/humanities, rich/poor, educated/uneducated, rural/urban, religious/secular, visually literate/illiterate, married/single, healthy/sick, young/old, politically engaged/disengaged, and so forth), but that they are socioeconomically defined, without a shred of a national agenda. Do we find common ground when dreaming of world peace? Is our singular national goal greater prosperity? Is that prosperity circumscribed by digital innovations? And will it be spread fairly across all socioeconomic classes?

One proposal for bridging the so-called divide between the sciences and the humanities, according to Friedrich Kittler, claims that there really isn’t a divide at all (so no bridge is necessary): everything worth studying must be measured, counted, and be given proportions. All areas are reducible into one nexus. In his words: “the only things that can be known about the soul or the human are the technical gadgets with which they have been historically measured at any given time” (Kittler 2010, 35). In light of this view that bridges the humanities and the sciences, there is a historical development, following Vilem Flusser, that allows Kittler to show how we have moved from the four-dimensionality of space and time to the three dimensions of obelisks, then to two dimensions of gravestones, to the one-dimensionality of text or print, all the way to the zero-dimensionality of numbers and bits in computers so as to avoid “any danger of concealment whatsoever” (Ibid., 226–227). What this process reveals is a deep commitment to reductionism – the view that multiple effects or events can be retrospectively reduced to a single antecedent or cause – as a way to make sense of the linear progression of technoscientific developments and the cognitive reflection that attends them. Unlike Snow, Kittler identifies only one culture.

In Kittler’s words: “When seen from this perspective, computers represent the successful reduction of all dimensions to zero. This is also the reason why their input and output consisted of stark columns of numbers for the first ten years after 1943. Operating systems like UNIX introduced the first one-dimensional command lines in the sixties, which were then replaced by a graphic or two-dimensional user interface in the seventies, beginning with the Apple Macintosh. The reason for this dimensional growth was not the search for visual realism, but rather its purpose was to open up the total programmability of Turing machines at least partially to users, which demands as many dimensions as possible due to the inconceivable number of programming possibilities” (Ibid., 227). For him, the transformation into fewer dimensions that then reverses into more dimensions is linked to human agency with specific needs for representation and control as means for comprehension and empowerment. He continues: “The transition to three-dimensional user interfaces (or even four-dimensional ones if time is included as a parameter), which today goes by the phrase ‘virtual reality,’ can of course also be understood as an expansion of the operational possibilities. Virtual realities allow for the literal immersion of at least two distant senses, the eye and the ear, and at some point they will also enable the immersion of all five senses. Historically, however, they did not originate from the immanence of the development of the computer, but rather from film and television” (Ibid.)

As illuminating as this rendition of the underlying similarity between the humanities and the sciences, there is also another layer of exposition that guides this historical narrative and that is warfare (see a fascinating parallel discussion of the development of computers – Turing machines – in the US in the hands of those developing the atomic and hydrogen bombs during World War II, Dyson 2012). Kittler is committed, ideologically and intellectually, to reducing and classifying all historical stages in warfare terms so that warfare as a motive and goal overshadows any sense of curiosity or play (that lead to technoscientific discoveries). For him, this “bombardment of the senses” is associated with warfare and more specifically with bomber pilot trainees (Kittler 2010, 228). Whether or not warfare is the underlying guide to bridging the purported cultural division Snow and Rabi worried about in the previous century, in this genealogy Kittler sets the tone for the dread and euphoria associated with contemporary digital technologies.

III Digital technophobes and technophiles

Despite the great diversity in contemporary culture, a diversity that probably could be detected in previous generations if the investigatory net were cast widely and deeply enough, there might be something that could inadvertently bring almost all of us together: digital technologies. Astrophysicists and grounds-keepers alike enjoy the use of cell phones and Global Positioning Systems as well as other gadgets provided by banks and fast-food franchisers even though their understanding of the internal workings of these instruments might radically differ. The Digital Age in this respect binds our culture in ways that would have been inconceivable a century ago. This is not to say that the differences among the different sub-cultures have been therefore erased or bridged; only to say that perhaps digital technologies could provide the means by which such erasure or bridging may come about (without resorting to Kittler’s reductionism).

According to David Berry, contemporary culture is a “computational knowledge society,” (2011, 3, emphasis in original), one whose uniqueness is actualized in its materiality (real storage units that emit heat and need to be cooled off) rather than some sense of its amorphous immateriality of the so-called cloud where data are stored or where computational activities take place. Following Martin Heidegger and Steve Fuller, he insists on the “concrete thing-in-the world-ness” of our computational culture (Ibid., 10). Overcoming the dichotomy between modernity and postmodernity, Berry suggests a difference between instrumental rationality and computation, so that “computational rationality is a form of reasoning that takes place through other non-human objects, but these objects are themselves able to exert agential features, either by making calculations and decisions themselves, or by providing communicative support for the user” (Ibid., 13). He calls this process without an end “an agonistic form of communicative action where devices are in a constant stream of data flow and decision-making which may only occasionally feedback to the human user” (Ibid., 14). Berry also emphasizes the importance of “digital intellect” rather than “digital intelligence” so as to add the critical dimension of the digital use with an eye on evaluating meanings rather than simply data in the context of “digital literacy,” hence moving the discussion way beyond the binary oppositions listed above to a new terrain that characterizes the twenty-first century (Ibid., 20).

What the written word and eventually the printing press were supposed to accomplish for modernity, digital technologies might accomplish for postmodernity: tools for enlightenment and greater happiness. This is the story of technophiles, the lovers of all things technical, who believe in the emancipatory power of technoscience. Perhaps they are simply echoing the belief in reason, a reasonable belief, since its claim for universality bridges all gaps of tradition, ethnicity, religion, and socioeconomic stratification. If an argument is valid, Aristotle already offered centuries ago, then no personal bias comes into play. If technoscience teaches us that a fact is true – gravity or the relation between energy, mass, and the speed of light – then it’s true for all of us, whether we are educated at Oxford or herd sheep in the hills of Afghanistan. This amazing revelation has carried the torch of enlightenment since the great scientific revolutions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It’s because of this single attribute of technoscience that the great humanists, as Snow called them, had to find a way to address the entire human enterprise, rather than worrying, as the British have for centuries, about their particular class distinction, or the Germans about their own unification after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. But just as digitized technoscience has its promise, so do the humanists share a concern for life and its meaning, as articulated by the existentialists for two centuries, as well as with human relations, such as friendship and love.

Members of the Frankfurt School, from Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno to Max Horkheimer and Herbert Marcuse, all the way to Jürgen Habermas, agree that a neo-Marxist critique of the advancement of technoscience in its capitalist trappings is essential in order to rescue civilization from its own abyss. It’s easy to confuse the critique with a strong sense of technophobia – a deep distrust of technoscience and digital technologies, almost a fear that they will push humanity beyond any potential redemption. But only if this critique is read as a Messianic protest will it be understood negatively. From Benjamin’s concern with the mechanical reproduction of works of art (1936) to Marcuse’s concern with the one-dimensionality of humanity (1964), it becomes clear that the critique is in fact a manifesto for salvation: humanity can find its soul again. This, perhaps, is the spirit of Heidegger who worried that the advent of technology would doom us to the machinery of our surroundings instead of the pristine comfort and authenticity of the Black Forest of his youth (1954). A contemporary critique, such as Kittler’s, is less romantic and more devastating, especially as he intertwines the onward march of mechanization and computation with warfare. For example, “Once storage media can accommodate optical and acoustic data, human memory capacity is bound to dwindle. Its ‘liberation’ is its end” (Kittler 1999, 10). Or, put in another way: “Mechanization relieves people of their memories and permits a linguistic hodgepodge hitherto stifled by the monopoly of writing … The epoch of nonsense, our epoch, can begin” (Ibid., 86). Or, even more critically: “The age of media (not just since Turing’s game of imitation) renders indistinguishable what is human and what is machine, who is mad and who is faking it” (Ibid., 146).

Unlike the Frankfurt School, Kittler’s reactionary modernism is almost postmodern in its liberal juxtapositions: “The history of the movie camera thus coincides with the history of automatic weapons. The transport of pictures only repeats the transport of bullets … Nothing, therefore, prevented the weapons-system movie camera from aiming at humans as well. On the three fronts of war, disease, and criminality – the major lines of combat of every invasion by media – serial photography entered into everyday life in order to bring about a new body” (Ibid., 124–128). “The typewriter became a discursive machine-gu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Digital Evolution in Postmodernity

- 2 Postcapitalism: Materialism, Decentralization, and Globalization

- 3 Political Economy: Freedom, Surveillance, and Entrepreneurship

- 4 Legality and Morality: Intellectual Property, Virtual Currency, and Corporate Responsibility

- Conclusion

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Digital Exposure by R. Sassower in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.