- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This collection examines the diverse material cultures through which early modern women's writing was produced, transmitted, and received. It focuses on the ways it was originally packaged and promoted, how it circulated in its contemporary contexts, and how it was read and received in its original publication and in later revisions and redactions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Material Cultures of Early Modern Women's Writing by P. Pender, R. Smith, P. Pender,R. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Women and the Materials of Writing

Helen Smith

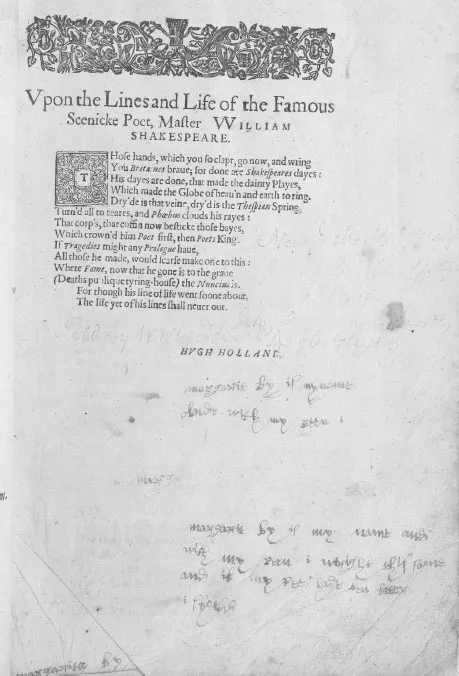

One copy of the 1623 Shakespeare First Folio, now at the Folger Shakespeare Library, is marked with the fragmentary testimony of a seventeenth-century woman (see Figure 1.1), about whom little is known, other than her name:

margarit by is my name and

with my peen I wright this same

and if my peen hade ben better

i sholld1

Margaret By’s broken final line doubly registers the allegedly stuttering presence of her pen: she not only writes about it, but also – by ceasing to write with it – calls the reader’s attention to the presence of the quill in her hand, and to the sometimes vexed relationship that existed between the writer and her tools. An aborted first attempt at the verse, along with one complete and two partial signatures, reinforces the link between literacy and pen-work, composition and inscription.

What By’s fragmentary testimony reminds us is that writing is an embodied act, undertaken by men and women who employ a range of specialist tools, and whose writing (in the sense both of script and of content) is shaped by the physical and social contexts in which it takes place.2 By’s verse is one of an array of ownership poems, signatures and inscriptions that mark the pages of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century books, and have been brought to light by scholars seeking to recover evidence of past reading. Reflecting on the relationship between ownership verses, pen practices, signatures and the texts they accompany, William Sherman asks: ‘are students of marginalia and readers’ marks supposed to study these inscriptions and, if so, how are they to be described and approached?’3 Sherman suggests we can interpret such fragmentary records variously as epigraphs, as sites of sometimes disruptive memory, or as acts of appropriation that take a canonical object (the book), and deploy it to new ends. Heidi Brayman Hackel further proposes that ‘marks of ownership and recording … contribute to a history of reading’, offering evidence of ownership and circulation.4 Yet in considering these marks as documents in the history of reading, there is a danger that we neglect their significance for the history of writing as a material, embodied and responsive practice.5

Figure 1.1 Inscriptions by Margaret By in a copy of the Shakespeare First Folio

Source: Folger Shakespeare Library, STC 22273 fol. 1, no. 32. Reproduced by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Where recent scholarship has encouraged us to understand women’s reading as a situated practice that took place in locations from the chamber to the open fields,6 this chapter turns instead to the places, and especially the tools, of women’s writing. It considers how the physicality of writing is made present as both the subject and the medium of women’s inscriptive practice. In his wide-ranging study of early modern epistolarity, James Daybell explains how writing has been made to matter along two trajectories. Materiality may be registered ‘in terms of the physical characteristics of manuscript letters and the meanings generated by them. … Such forms were imbued with social signs and codes that affected meaning.’7 Thus in The Gentlewomans Companion (1673), Hannah Woolley concluded her instructions on the appropriate contents of a letter with a stern reminder:

Have especial care of blotting your paper, giving it a large Margent; and be curious in the cutting your Letters, that they may delight the sight, and not tire the Reader. Lastly, be curious in the neat folding up your Letter, pressing it so that it may take up but little room, and let your Seal and Superscription be very fair.8

Alongside questions of layout and presence, Daybell argues, ‘the term materiality also encompasses the “social materiality” of letter texts, in other words the social and cultural practices of manuscripts and the material conditions and contexts in which they were produced, disseminated and consumed’. In this chapter, I want to extend Daybell’s taxonomy still further by exploring two additional modes of thinking materially, tracing the encounters between early modern women writers and their tools of writing, and the relationship between written (and printed) objects and subject matter.

The first half of this chapter attempts to reorientate our understanding of women’s relationship to the objects of writing, and is inspired, in part, by Sara Ahmed’s demand for a ‘queer phenomenology’, a rethinking of the relationships between people and their environments that recognises how the material presence of objects imposes certain attitudes and directions of approach. A body, Ahmed argues, ‘gets directed in some ways more than others. … If such turns are repeated over time, then bodies acquire the shape of such direction.’9 Ahmed returns repeatedly to the question of women’s place at the table: the foundational object of phenomenological thought.10 It is at the table that Edmund Husserl’s famous meditation upon situated perception, and hence the scholarly field concerned with how we come to know the world around us, begins.11 As Ahmed points out, Husserl’s table for writing and thinking is somebody else’s (a woman’s) job of tidying, cleaning and sorting;

Ahmed asks ‘Who faces the writing table? Does the writing table have a face, which points it towards some bodies rather than others?’12 This chapter (this ‘paper’), then, pursues the early modern functions of paper, ink and quills in order to recognise some of the alternative directions from which early modern women approached and appropriated the practice and place of writing.

Husserl defines ‘perception’ as ‘an attentive perceiving’: ‘I am turned towards the object, for instance, the sheet of paper; I seize upon it as this existent here and now. The seizing-upon is a singling out and seizing.’13 In directing his attention towards ‘the paper’ – an example that is far from arbitrary, given that it is precisely the surface upon and with which he is working – Husserl distinguishes it from the ‘background’ of ‘books, pencils, an inkstand, etc’, which are ‘also “perceived” in a certain manner, perceptually there, in the “field of intuition”’. In the second part of this chapter, I follow the line of Husserl’s directed perception, turning to the ways in which writing materials become the subjects of inscription, emerging as the matter of writing in a triple sense: not only as the materials that make writing possible, but as the subject matter (the res) of that writing, and as frames for and participants in the processes of composition and cognition.

‘Necessaries for writing’

In the directions to ‘such as desire to be Waiting Gentlewomen’ that open The Compleat Servant-Maid; or, the Young Maidens Tutor (1677), Woolley concludes a section on syrups with the remark: ‘Thus having given you some short directions for Preserving, Conserviug [sic], and Candying, I shall in the next place give you some rules and directions, how you may attain to write a good legible Hand.’14 Accompanied by a set of elegant foldout engravings demonstrating complex letters and flourishes, Woolley’s directions begin with making the pen, a process that requires the would-be writer to have a ‘penknife with a smooth, thin, sharp edge’ and to ‘take the first or second quill of a Goose wing and scrape it’ before cutting a nib.15 Arguing that Woolley categorises ‘handwriting as a basic skill of housework’, Wendy Wall suggests that these instructions rely upon the skilled servant’s ability ‘to wield a knife properly in order to chop ingredients, shape pastries, and carve at the table’.16 In The Compleat Servant-Maid, this congruence is striking: only fifteen pages after learning how to make a pen, the reader receives instructions on ‘How to Rear or Break a Goose’, returning us abruptly to the carcass that was the source both of writing implements and of roast meat.17

Woolley goes on to instruct her reader how to hold the pen, and then, in a paragraph that reminds us of the bodily and situated nature of writing, ‘How to sit to write’. Asserting the importance of physical self-discipline, Woolley directs the reader: ‘hold your head up the distance of a span from the paper, when you are writing hold not your head one way nor other, but look right forward’.18 With her right elbow drawn in, and left hand steadying the paper, the novice writer is also asked to consider her materials, ensuring she is possessed of thin, freely flowing ink, and ‘white, fine, and well gumm’d’ paper.

At this point, Woolley’s guide to writing becomes difficult to distinguish from the numerous instructions for culinary and medical practice that accompany it in the printed text; she directs her reader: ‘Rub your paper lightly with gum-sandarac beaten fine, and tyed up in a linnen cloth, which makes the paper bear ink better, and the pen run more smooth’.19 Sandarac (red arsenic sulphide) was otherwise used for medical treatments or as a poison. In tone and form, Woolley’s directions for paper-preparation chime with the receipts that elsewhere guide users to prepare and preserve a range of fabrics and of sweetmeats. Woolley’s guide prompts us to reorientate our approach to women’s writing, recognising that we might approach women’s literacy from the direction of domestic practice and utility, rather than as an aspiration to an elite male preserve.

Figure 1.2 reproduces a portrait of Mary Neville, Lady Dacre, engaged in the act of writing. As well as her quill, Neville is equipped with an open pot of ink, with its cover re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Early Modern Women’s Material Texts: Production, Transmission and Reception

- 1 Women and the Materials of Writing

- 2 Dispensing Quails, Mincemeat, Leaven: Katherine Parr’s Patronage of the: Paraphrases of Erasmus

- 3 ‘Le pouvoir de faire dire’: Marginalia in Mary Queen of Scots’ Book of Hours

- 4 Translation and Community in the Work of Elizabeth Cary

- 5 The ‘Great Queen of Lightninge Flashes’: The Transmission of Female-Voiced Burlesque Poetry in the Early Seventeenth Century

- 6 Katherine Philips, ‘Philo-Philippa’ and the Poetics of Association

- 7 Late Seventeenth-Century Women Writers and the Penny Post: Early Social Media Forms and Access to Celebrity

- 8 Henrietta’s Version: Mary Wroth’s Love’s Victory in the Nineteenth Century

- 9 ‘One of the Finest Poems of that Nature I ever Read’: Quantitative Methodologies and the Reception of Early Modern Women’s Writing

- Bibliography

- Index