eBook - ePub

Regions, Industries, and Heritage.

Perspectives on Economy, Society, and Culture in Modern Western Europe

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Regions, Industries, and Heritage.

Perspectives on Economy, Society, and Culture in Modern Western Europe

About this book

The industrial age has proved to be a formative period for Europe. Industrial heritage nowadays bears witness to the development that took place in differently structured regions. This volume presents different paths of industrial development and gives an overview of the concepts of regions, used among economic, social and cultural historians.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Regions, Industries, and Heritage. by Juliane Czierpka, Kathrin Oerters, Nora Thorade, Juliane Czierpka,Kathrin Oerters,Nora Thorade in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Industrialization, Regionalization, and Spatiality: An Examination of Regions during Their Industrial Development

3

The Ulster Linen Triangle: An Industrial Cluster Emerging from a Proto-Industrial Region

Marcel Boldorf

Whether Northern Ireland can really be regarded as an example of a successful transition into the age of industrialization is the subject of some academic debate. Researchers who take the situation of the whole country into consideration, especially focusing on the Great Famine of the 1840s, tend to a hold onto a rather pessimist view. Particularly, when the Irish development is compared to British industrialization, the effects of de-industrialization and the peripheral state are highlighted (Ó’Gráda, 1988). A variation of this is to speak of ‘Ireland’s industrial decline in the nineteenth century, outside eastern Ulster’ (Clarkson, 1996, p.83). This view takes into account the rapid growth of the linen industry in a specific part of Ulster, the northernmost of Ireland’s ancient provinces. One cannot deny that the history of the Irish has been strongly linked to hunger and pauperism, primarily in sectors such as hand-spinning which, at a certain stage, lagged behind in productivity, thus suffering a slump in earnings (Ollerenshaw, 1985, pp.67–9). However, there might be some evidence for more optimism regarding the province of Ulster, especially when its economic performance is compared to other cases in continental Europe (Boldorf, 2003). A full comparison with other European regions is not the intention of this contribution. The optimistic perspective is assumed as a starting point, and the aim is to present a more complete view of Irish industrialization.

The chapter’s methodological foundation is built upon the concepts of industrial districts and clusters. The latter defines regions as geographic agglomerations of companies, or here linen producers, which are linked by externalities and complementarities of various types (Porter and Ketels, 2009, p.173). Again, the two competing approaches cannot be discussed here in depth. Instead, the less contradictory and more general outlines of the two concepts will be at the basis of the argumentation: the concentration of industries within a region, forming a geographical agglomeration of industrial producers and suppliers. In order to explain the emergence of an industrial cluster, the following will present the various forms of regional trade activities and the organization of production. It will be highlighted that industrial development depended on institutional factors which promoted internal development. The Northern Irish case is characterized by a major shift in textile production. From the last decades of the 18th century, a cotton machine-spinning cluster emerged which, from 1825 onwards, transformed into a linen cluster.

The contribution is structured as follows: the first section describes the origins of the rural industries which were not only closely connected to the agrarian situation but also to political factors. Then, the analytical concept of regional industrialization will be applied to the particular example of Ulster, followed by explanations of the organization of inner-regional trade. Thirdly, the emergence of a cotton cluster within the region is analyzed, while lastly, the concluding section outlines its transformation into a linen cluster. Thus, the chapter provides an overview of how 19th-century Northern Ireland became the world’s most important exporter of linen products.

The foundation of the Irish linen industry

Large parts of Ireland were not suitable for agriculture due to the land being infertile. However, sheep-farming was widespread and the production of woollens had a long tradition. In large parts of the country, the rural workforce was underemployed for several months of the year and a market-oriented production of frieze, a coarse woollen cloth which had been used for generations by Irish peasants for their own clothing, started in the second half of the 17th century. As export opportunities to England arose, auxiliary employment in the production of woollens increased. At the end of the century, around 30,000 Irish households were occupied in the rural woollen industry (Cullen, 1972, pp.23–4). At the same time, there was growth in the planting and production of flax, which was mostly spun into linen yarn and sold to Britain.

The rural linen industries continued expanding in the 1680s. As part of the Plantation of Ulster, large tracts of land in the province were acquired by English or Scottish owners. As a result, the property rights of the local population were severely reduced: ‘One of the most important and disastrous of the penal laws’ (Gill, 1964, p.24) of 1702 forbade the long-term leasing of land to the Irish Catholic population. Instead, the British government fostered long-term leasing to Protestant landowners in order – ostensibly at least – to give them the chance to improve the quality of the soil. But the new group of owners was more interested in speculation than in improving the agrarian situation. As a result, short-term leases to Catholic sub-contractors became a feature of Ulster.

The impact of short-term leasing was permanent uncertainty among the leaseholders surrounding their income. Many of them decided to grow flax and earn their livelihood from spinning. Both activities could be easily financed up front – in contrast to sustainable farming. Very often, the profitable activity of linen weaving was added to the household’s activities. This particular situation explains why the flood plains of the rivers Bann, Lagan and Foyle had considerable proto-industrial activity despite offering favorable conditions for agriculture. The assumption of the proto-industrialization theory that poor agrarian conditions explain the growth of rural industries holds true for only parts of Ulster (Kriedte, Medick and Schlumbohm, 1981, p.14).

Stimuli from abroad promoted the further expansion of linen spinning and weaving. The first linen shipment to London was recorded in 1682 (Crawford, 1988, p.33). In 1696, the English government allowed the duty-free import of all sorts of coarse and white linens (Clarkson, 1989, p.261). In 1705, linen exports to the British overseas territories were permitted and Irish linen began to compete with products from central Europe in those markets. Another stimulus was the arrival of Quakers from northern England from 1650 onwards and, later, the immigration of French Huguenots. Conrad Gill explains the location of linen weaving in northern Ireland primarily through their settlement (Gill, 1964, pp.20–2). William Crawford points out that linen weaving was practiced on 500 looms before the Huguenots’ arrival (Crawford, 1980). He wanted to put into perspective the role of potential entrepreneurs such as Louis Crommelin who in later parliamentary debates claimed to be the doyen of Irish linen manufacture. In any case, the density of Protestant settlement was highest in the counties of Antrim, Down, Armagh, Tyrone and Londonderry, which later formed the core of the proto-industrial linen region. Local centers were towns such as Lisburn or Lurgan, to the west of Belfast. The foreign settlers brought important skills with them into the country, documented in Crommelin’s book An Essay towards the Improving of the Hempen and Flaxen Manufactures in the Kingdom of Ireland, published in 1704. The immigrants were important in two respects for Irish linen manufacture (Clarkson, 1989, p.260). Firstly, they introduced into Ulster the production of fine linens, damask and diapers. These innovations were utilized by a number of Lurgan bleachers such as Thomas Turner, James Bradshaw, John Nicholson and John Christy in the first decades of the 18th century (Crawford, 1980, pp.114–15). Secondly, they used their contacts with the parliaments of Dublin and London to improve the situation of linen manufacturing. In 1711, the Irish Parliament introduced the Board of the Trustees of the Linen and Hempen Manufactures of Ireland, the Linen Board (Corry, 1784). The Board’s task was to promote the manufacture of linens across the whole of Ireland.

Mapping the linen region

Shaping the industrial region of Ulster is more complicated than in other European examples because in the 18th century data on means of production (weaving looms) or employment (number of persons occupied with spinning or weaving) were not recorded for small territorial units such as districts, counties or parishes. So far, we have seen that with respect to linen manufacture, Ulster was obviously the most important among the four Irish provinces. It consisted of nine counties: Donegal, Londonderry, Antrim, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Armagh, Down, Monaghan and Cavan. But many indicators suggest that the linen region consisted of only five of these counties. At the very end of the proto-industrial period, when data on employment is available, the census of 1841 revealed that industrial employment was by far higher in Antrim, Armagh, Down, Londonderry and Tyrone than in the other counties of Ireland (Clarkson, 1996, p.76). It can be assumed that the five counties were previously also the richest in terms of industrial activities. The classification according to employment criteria is particularly unreliable in the Irish case because larger parts of the linen region offered favorable agrarian conditions. In Ulster, a type of weaver household was prevalent which included all stages of the production process under one roof: from flax growing and preparation to yarn spinning and hand-loom weaving. On the part of the cultivated land that was not needed for subsistence production, flax was grown. Spinning was a production stage that was always done by female household members, whereas the weaving looms were operated by men. It was the children’s and servant’s duty to do the preparatory and post-processing work around spinning and weaving.

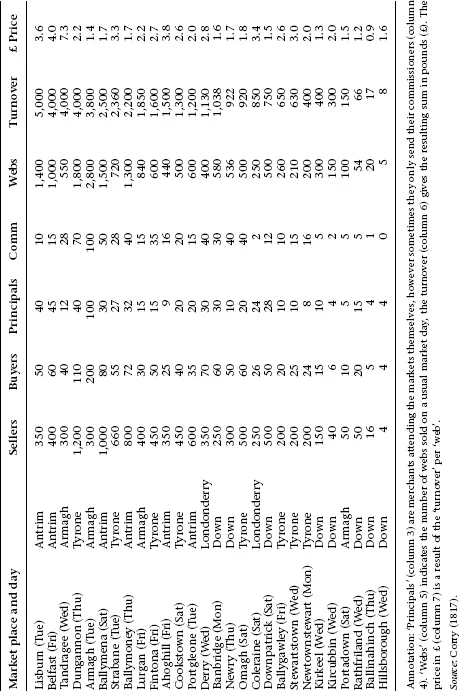

Circumstances changed when the shortage of land was intensified as a result of population growth. More and more families could not grow their own flax any longer and had to buy yarn on specialized markets. Thus, the importance of flax and yarn markets grew, and the primary and intermediate products were delivered to Ulster’s markets. Yarn jobbers came from counties outside Ulster such as Sligo, Mayo, Leitrim or Meath to sell linen yarn (Gill, 1964, pp.38–9). The spatial distribution of linen markets, too, can be used as an indicator to map the industrial region. The concentration of those markets in Ulster is documented in the two reports of the Linen Board’s secretary, James Corry, established for the years of 1816 and 1821 (Corry, 1822). At this time when rural industries were already widespread, his overview encompassed 70 flax and 50 yarn and linen markets. Flax markets were also located outside the five proto-industrial counties, especially in Donegal, whereas the linen and yarn markets were concentrated in Antrim (6), Armagh (4), Tyrone (8), Down (8) and Londonderry (2) as we can see in Table 3.1, extracted from Corry’s report.

Table 3.1 shows the markets in order of turnover. The markets with high turnover lay in the counties of Antrim (£2773 on average) and Armagh (£2450), with average turnover in Tyrone (£1483) and Londonderry (£990), and low turnover in Down (£438). The best-selling markets were to be found in a line running south-west of Belfast to Armagh, among them Lisburn, Lurgan and Tandragee. Together with Banbridge and Newry, they were diversified markets where not only simple linen sorts were sold but also the more expensive fine cloths. Therefore, they had the highest prices per web (column 7). The types sold there were the so-called lawns (used for producing handkerchiefs and children’s clothing), diapers and damask-diapers. The area marked by the towns of Lisburn, Dungannon and Armagh (the south of Antrim, the centre and west of Down, and the north of Armagh) is called the linen triangle (Crawford, 1988, pp.48–9). The three other sub-regions were (a) north-western Ulster (Co. Tyrone and Co. Londonderry) known for three-quarter wide linens (3/4) and 7/8 linens called Tyrones and Coleraines, (b) northern Antrim with the central markets of Ballymena and Ballymoney producing ‘three-quarters’ as well and (c) the south of Armagh with the speciality of one-yard-wide Stout Armaghs, another type of coarse brown linen. Thus, in 1816, the linen region was segmented in the different zones, corresponding with specific frameworks of trade relations. Apparently, the eight markets of Co. Down did not play an important role any more. Corry’s report records a rather advanced stage of the proto-industrial development. The putting-out system had already emerged in eastern Co. Down, leading to the decline of local markets. In the next paragraph, the organization of trade will be explored in more detail.

Table 3.1 Ulster linen markets, 1816

The organization of trade

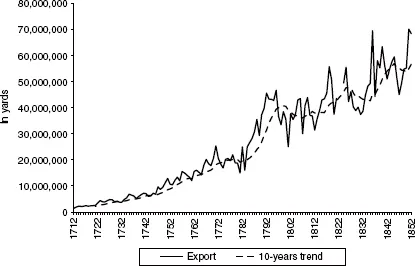

Before analyzing the structure of trade within Ireland, the county’s exports must be examined because they explain the dynamics of rural industrialization over time (Figure 3.1).

In contrast to the increases and decreases due to wars and other troubles in continental Europe, Irish export statistics show steady progress (Horner, 1920, p.407). In the 1780s and early 1790s, the amount of linen exports doubled from 20 to 40 million yards. They stayed at that level for the two first decades of the 19th century, thus the crisis years of 1801, 1807 and 1812 can be neglected. In 1818, export exceeded 50 million yards for the first time, and underwent a further increase in the era of mechanization that followed.

In 1771, half the Irish exports were shipped to England from the port of Dublin: 30 per cent from Belfast and 14 per cent from Newry (Stephenson, 1784, p.87). The rest was distributed via smaller ports such as Drogheda, Cork, Derry, and Coleraine. Belfast rapidly caught up as linen exports grew in the 1780s, and ultimately became the main shipping location. Most of the entrepreneurs involved were successful linen bleachers who possessed the capital to get involved in trade. With the support of the drapers, linen traders who had formerly sold their goods in Dublin, the Belfast Linen Hall was erected in 1785; this meant the end of the heyday of the drapers, which had lasted from 1740 to 1780. This group of merchants had believed that the system of public markets provided them with the most efficient method of purchasing the linens they required. They relied on the certainty that the quality of the cloth was uniform throughout each piece and that its minimum measurements were guaranteed (Crawford, 1988, p.42).

Figure 3.1 Irish linen exports, 1712–1852

Source: Gill, 1964, pp.341–3; Solar, 1990, p.69.

In the 1780s, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 2 Regions Revisited: The Importance of the Region in Understanding the Long-Term Economic and Social Development of Europe

- Part I Industrialization, Regionalization, and Spatiality: An Examination of Regions during Their Industrial Development

- Part II Industrial Heritage, Identities, and Regional Self-Perception: An Examination of Regions after Their Prime

- Index