![]()

1

Introduction

Energy is often said to be the lifeblood of modern society. It enables us to fulfill our basic human needs and it powers the world economy. Yet, the energy path we are currently on is clearly unsustainable. Our massive combustion of fossil fuels – that is, oil, coal, and natural gas – unleashes tons and tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, causing the global climate to warm at a destructive pace. Dwindling conventional reserves make these fuels increasingly expensive to extract and force companies to venture into unconventional oil and gas production, which brings with it a host of environmental and social concerns. In addition, the upstream oil and gas sector continues to be associated with corruption, bad governance, and human rights abuses. At the same time, about a quarter of the world’s population lacks access to electricity and to the basic services it provides.

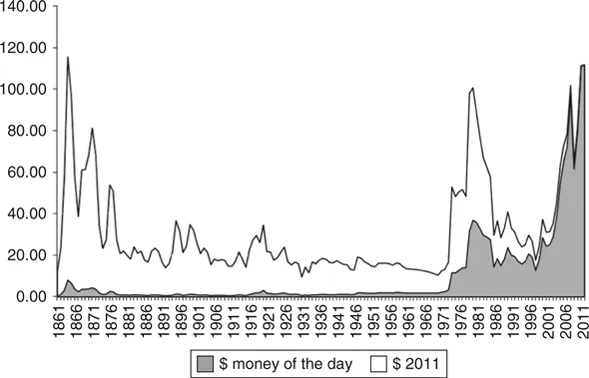

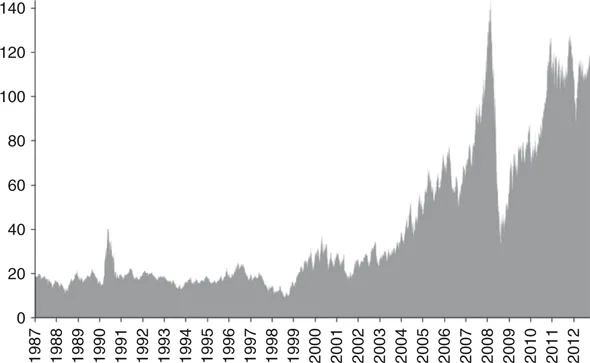

The combination of an exploding energy demand, rising extraction costs, and shrinking low-cost reserves has lifted crude oil prices to record highs in recent years. Oil prices reached an historical peak in the summer of 2008, when almost 150 US dollars was paid for a barrel of oil. The financial crisis that erupted afterwards, and which some analysts (for example, Hamilton 2009) link with high oil prices, temporarily eased some of the most acute pressures that were present in the global energy order by putting the brakes on global oil demand. In 2009, global oil consumption dropped for the first time since 1982. Oil prices tumbled from nearly 150 dollars a barrel in July 2008 to about 40 dollars a barrel in November of the same year. In the following months, prices stabilized at slightly above that level, fluctuating between 60 and 70 dollars a barrel throughout 2010.

Pretty soon, though, it became clear that the economic crisis had only stalled, not canceled or reversed, some of the most worrisome global energy trends. As the economy recovered and oil demand picked up, particularly in emerging economies, oil prices rebounded to 90 dollars a barrel in December 2010. In the early months of 2011, political unrest in the Arab world pushed prices even higher and, in April 2011, a barrel of Brent oil was traded at more than 125 dollars. The failure of the main oil-exporting countries to agree to a production rise in early June prompted the major Western countries to jointly release oil from their strategic stocks, only the third time ever they have done so. In 2012, the oil price averaged 112 dollars a barrel, the highest yearly average in history.

Although oil prices may continue to ricochet back and forth in the coming years in response to short-term events, there appears to be a structural trend to higher and more volatile prices (McNally and Levi 2011). Figures 1.1 and 1.2 give an historical overview of world oil prices.

High petroleum prices are but one expression of the profound changes that are currently afoot in the global energy system alongside other worrying trends such as climate change, the proliferation of nuclear weapons, and the growing anxiety about energy security. Taken together, these trends indicate that our global energy system is not ‘healthy’ and that we need to massively and rapidly alter global energy production and consumption patterns. To many observers it is clear that, since the challenges that energy poses transcend national borders, so must our policy responses. Against this backdrop, this book examines how the energy sector is regulated and governed at the international level, why this governance architecture looks the way it does, and how these rules and institutions are coping with the dramatic transformations that characterize the global energy landscape.

Figure 1.1 World crude oil prices, 1860–2012 (USD, yearly averages)

Source: British Petroleum, www.BP.com.

Figure 1.2 Brent oil price, 1986–2011 (USD, daily)

Source: US Department of Energy, www.eia.gov.

Problem definition

Commercially traded energy is not just another private commodity. It is what classical economists call a ‘basic good’, or a good that, directly or indirectly, enters into the production of every other produced commodity or service (Rühl 2010). Political scientists tend to describe nonrenewable fossil and nuclear fuels as ‘strategic goods’, that is, goods with a relatively high utility for which there are no readily available substitutes (Baldwin 1985). Uninterrupted access to such strategic goods as oil and gas is critically linked to national security, economic development, and social peace. Energy prices can determine the electoral fate of political leaders, as was demonstrated again in February 2013 when the Bulgarian prime minister quit following mass protests over the price of electricity.1 It is therefore not surprising that governments tend to exert some sway over the energy sector rather than leave it entirely in private hands. Nevertheless, the state–market pendulum has swung markedly throughout modern history in response to price developments, changing perceptions of externalities associated with the energy sector, and shifting ideological preferences about the appropriate role for government in the economy (Finon 1994; McGowan 2008; Goldthau 2012).

Even so, governments have never fully relinquished control over the framework within which energy markets operate. In fact, it is hardly possible for governments not to have an energy policy. The United Kingdom tried, under Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, to do without one, abolishing its energy ministry and applying the same set of competition and liberalization rules to energy as to any other sector. Yet, even under Thatcher’s rule, tough regulations enforced by an independent regulator were necessary to ensure sufficient competition (Buchan 2002). In modern times, the government has always been a major, if not dominant, player on energy markets and privatization has not changed this. As Helm (2002, 174) observes,

it changed the form of interventions, and the mechanisms of influence shifted from the boardrooms of nationalized industries to more explicit policy instruments and regulatory control. But the idea that governments could simply retreat from the scene and leave it to competitive markets is an illusion – energy is just too important to the economy and society, and [it] suffers from multiple market failures.

Energy markets are indeed notorious for suffering from gigantic market failures. A market failure can arise if there are externalities, such as pollution, or if there are inefficiencies associated with market structure, such as a cartel or incomplete information. As a result, some form of public policy is warranted to provide the public goods that energy markets fail to deliver by themselves (Coase 1960). Regulation of energy markets is not only required at the national level. It also needs to extend beyond the confines of the nation state for the simple reason that most energy markets, as well as the externalities they generate, are transnational in nature (Goldthau 2011; Florini 2012; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al. 2012). Issues such as resource scarcity, climate change, electricity deprivation in the South, and enormous investment needs on a global scale represent only the beginning of a long list of energy-related problems that need to be tackled by governments around the world. Since these issues have an essential transnational scope, it is difficult for individual governments operating in isolation from each other to handle these problems effectively. In other words, energy is an issue endowed with all the ingredients that call for, even necessitate, some form of multilateral cooperation and policy-coordination. The United Nations (UN) even considers energy to be ‘perhaps the topmost sector on the agenda of issues in need of global management’ (UN-Energy 2006, 1).

For most policy fields that are transboundary in nature, states have sought to create a set of international rules and norms, often administered by international organizations and their secretariats. These organizations have primarily been embedded within the UN system, although numerous spheres of institutionalized cooperation have developed outside of it, particularly in recent years. Thus, states have created international institutions for a set of transboundary issues ranging from climate change (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) to international trade (World Trade Organization), communicable diseases (World Health Organization), and global finance (International Monetary Fund). However, despite the inherently transboundary and interlinked nature of the global energy challenges, there is no single multilateral framework regulating the production, trade, transit, and consumption of energy. There is no UN World Energy Organization nor even a clearly identifiable global energy regime. This observation is not new. Already in the early 1980s, some observers thought it was ‘extraordinary and anomalous that, despite the importance of energy problems within the world economy today, no international body with this responsibility yet exists’ (Luard 1983).

Of course, the absence of a World Energy Organization does not mean that there is no multilateral energy cooperation whatsoever. In fact, there exists a complex and fragmented landscape of parallel, overlapping, and nested institutions that vary along a spectrum in terms of their spatial and functional scope, membership, and effectiveness. Yet, overall, the degree and density of institutionalized energy cooperation is relatively limited compared to other transnational issue areas. For health, for example, the global organizational field today includes some 2600 health-related organizations (Inoue and Drori 2006). A cursory search for energy organizations in a database of intergovernmental organizations from the nineteenth century to 2000, compiled by Pevehouse et al. (2004), resulted in only seven hits.2

In addition to the relatively low institutional density, the existing institutional framework to regulate the energy sector at the international level looks utterly outdated. The international energy governance architecture largely took shape in response to the oil shocks of the 1970s. Structural shifts in international energy markets have put this global architecture under increasing strain. Particularly since the turn of the millennium, world energy markets have been profoundly shaken by the rise of heavyweight energy consumers such as China and India, the increasing scarcity and rising production costs of conventional oil, the growing impact of climate change on energy policies worldwide, and the re-emergence of state players on oil and gas markets. These trends pose significant challenges for the existing global energy institutions, which appear unable to assist the world community to navigate smoothly through a sustainable energy transition. As it stands, the global energy architecture is weak, fragmented, incomplete, and obviously ill-adapted to the scale and scope of energy problems at hand.

In response to the widely perceived inadequacy of the current global energy governance arrangements, a number of voices have made concrete proposals to establish new treaties and institutions, or to strengthen existing ones. Victor and Yueh (2010), for example, propose to establish an Energy Stability Board similar to the Financial Stability Board, which coordinates the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies in global finance. Mohamed El-Baradei, former director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency, pleads for the creation of a World Energy Agency.3 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev proposed setting up a new multilateral energy treaty at the 2008 G8 meeting (van Agt 2009).4 His Turkmen counterpart, President Gurbanguly Berdhimukhamedov, has taken the initiative to form a special Energy Council under the aegis of the United Nations.5 And even the former Chinese Prime Minister, Wen Jiabao, joined the chorus in January 2012, when he called for a new ‘global energy market management mechanism for mutual benefit, under the framework of the Group of 20’.6

Rather than suggesting quick institutional fixes to the weak and scattershot energy architecture, I am interested in examining why we have this inadequate set of energy governance institutions. By studying the whole array of institutions governing an issue area rather than an individual international institution, this research ties in to a broader trend in the literature. It is increasingly argued that it no longer makes sense to study international institutions in isolation from each other. The reason is that, today, owing to the proliferation of international rules, institutions, and regimes, almost no issue is governed by a single institution.

Reflecting this institutional proliferation, the focus of global governance studies is increasingly shifting away from discrete institutions to the study of ‘regime complexes’ (Raustiala and Victor 2004; Alter and Meunier 2009; Orsini et al. 2013) or ‘governance architectures’ (Biermann et al. 2009). Both concepts refer to the interlocking governance structures that lie between the poles of a fully integrated legal system on the one hand and total fragmentation on the other (Keohane and Victor 2011). Raustiala and Victor define a regime complex as ‘an array of partially overlapping and nonhierarchical institutions governing a particular issue-area’ (Raustiala and Victor 2004, 279). Biermann and colleagues define a governance architecture as ‘the overarching system of public and private institutions that are valid or active in a given issue area of world politics’ (Biermann et al. 2009, 15). Since those definitions largely coincide, I will use both terms interchangeably.7 Institutional overlap can be conceptualized in terms of membership, mandate, and resources (Hofmann 2011).

Within that larger debate on institutional patchworks, this work explores the origins, design, and evolution of the global energy architecture. In an attempt to move away from the static analysis of regime complexes and institutional design (Abbot and Snidal 1998; Koremenos et al. 2001), this book examines how the patchy and fragmented energy architecture came about and how it has responded, or failed to respond, to pressures for institutional change. Instead of taking institutional complexity for granted, I want to understand by which forces and actors it is shaped, which norms it embeds, and which distributional consequences it yields.

The central research question I aim to address is the following: How and why did the inadequate and fragmented global energy governance architecture emerge and develop over time? The underlying hypothesis of the book is that the insufficient global institutional answers to the pressing energy problems are rooted in the evolutionary nature of international energy governance regimes. In contrast to specific international organizations, regime complexes are barely negotiated, but they emerge almost tacitly through processes with low degrees of intent. Adopting a dynamic lens to examine the patchwork of global energy institutions, I contend that the fractured landscape for energy governance was not planned, but evolved piecemeal. Put differently, the architecture that actually emerged owes more to historical accident than to purposeful design. Understanding how this architecture came into being and how it evolved could lead to more informed decision-making and knowledge on how it can be changed.

This way, my research responds to David Lake’s (2010, 609) recent call for more inquiry into ‘the prospects and strategies for reform of the global architecture’. Lake (2010, 609–610) further contends that

[The] current system of global governance has arisen incrementally, spontaneously, and organically over a long period of time. It is highly unlikely that this system is anywhere near efficient or optimal even for current actors. [The] case for reforming the global architecture is strong. [Our] primary duty as scholars is to describe and explain the world around us. A second duty, however, is to propose and examine realistically prospects for progressive reform.

Heeding Lake’s call, the objectives of this book are fourfold: first, to map and evaluate the currently existing global energy governance rules and arrangements against an explicit normative framework of where governance is needed; second, to explain why overlapping institutions have emerged in global energy governance; third, to trace and interpret the emergence and development over time of the energy regime complex as a whole; and fourth, to present informed insights on the drivers, obstacles, and options for reforming some key component institutions of the global energy architecture.

Literature review

Although the importance of energy for the world economy can hardly be overstated, energy has remained curiously under-studied by scholars of International Relations (IR). In contrast to the well-established bodies of literature in issue areas such as trade, security, and the environment, there is no comparable set of writings on energy. To be sure, the turbulent oil markets of the last decade have spawned a plethora of bestselling books on energy. These works often carry sensational titles that are reminiscent of a similar stream of literature in the 1970s, the era of the politically driven oil shocks.8 Yet, many of the recent books on ‘energy security’ are destined for a wide audience and rarely, if ever, engage in proposing or testing scientific propositions. The issue area of energy thus offers a rich but underexplored empirical ground on which to explore new directions in international relations theory (Florini and Sovacool 2011).

Those academics who have studied international energy relations have mainly done so from neorealist, geopolitical, and hard-nosed security perspectives (for example, Klare 2008). Scholars have only recently come to approach the subject from a different angle, that ...