eBook - ePub

Political Parties in Multi-Level Polities

The Nordic Countries Compared

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Political Parties in Multi-Level Polities

The Nordic Countries Compared

About this book

Political parties are essential for the functioning of parliamentary democracy but how have parties adapted to the challenges created by the growth of a new layer of political decision-making at the supranational level, i.e. the EU? This comparative survey focuses on parties in four Nordic countries, including Norway, which remains outside the EU.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Political Parties in Multi-Level Polities by Nicholas Aylott,Magnus Blomgren,T. Bergman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Parties and the Challenge of Multi-Level Politics

For all the changes in European governance in recent decades, which some suggest have left the old ‘boundaries’ of the state out of sync with each other (Bartolini 2005), national democratic systems remain the centrepiece of politics. Moreover, despite their frequently alleged decline (see Daalder 1992), parties remain absolutely central to political competition. It is hard to envisage a genuine alternative to them so long as parliamentarism remains the democratic system of choice in the majority of European countries.

Yet the conditions in which parties operate have unquestionably changed. Party-based democracy – which, in practice, is a reasonable synonym for parliamentary democracy – has been firmly associated with the national state. Nationally delimited elections mean nationally delimited parties. But what happens when the national parliament is no longer unequivocally the highest political authority in the state, as is the case in the modern European Union?

Since the European Court of Justice established the primacy of European law over national law, and since the Single European Act introduced the real possibility of member states being outvoted in the Council of Ministers, accountability through parties has been harder to exercise. A minister can hardly be sanctioned by his or her government if he or she strove to pursue the preferences of both parliament and government in negotiations with counterparts from other member states, but failed to win them over. Nevertheless, the policy that those other member states’ ministers preferred will become law in the recalcitrant state all the same. This, in essence, is a big part of the much-discussed ‘democratic deficit’ in the EU. It is deepening in tandem with the expanding policy competencies of the Union (Follesedal and Hix 2006: 534–7). In short, the EU is creeping into ever more areas of public policy, but its authority is not being held properly to account – not, at least, according to traditional democratic measures.

A great deal of research, both normative and empirical, has been devoted to this democratic deficit. The vast majority of it focuses on the institutions of the Union. Only a small, albeit growing, section takes up the effect of European integration on national political parties, and only a small proportion of that looks inside the parties at the internal mechanisms of democratic accountability that they contain.

This book is part of an attempt to help fill that gap. It reports the findings of a research project that investigates the state of delegation and accountability in Nordic political parties – that is, the parties represented in the national parliaments of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The aims of the project are threefold.

First, it seeks to peer into the black box of party organisation, and to do so through a distinct conceptual lens. In doing so, we hope to derive a clearer understanding of how power within parties is delegated and accountability exercised. Second, the project compares these mechanisms of delegation and accountability according to how they work at two different levels: at the customary national level and at the EU level. Of course, such a comparison will be of limited scale in the parties operating in one of the two Nordic non-EU member states, Norway. But it is far from meaningless even in those cases, thanks to the two countries’ involvement in European integration via the European Economic Area (EEA). Third, the project aims to compare these mechanisms across cases – that is, to shine a comparative light on the way that parties operate across the Nordic region, with particular emphasis on the effect of European integration.

In sum, ours is a study of political parties’ role in the multi-level polities – or perhaps even polity, in singular – that much of Europe has become, with our empirical material drawn from the Nordic region. The study draws inspiration from previous research that models modern representative democracy as a chain of relationships. Each of these relationships involves one actor delegating tasks to another actor, with the first actor then holding the second accountable for executing the tasks satisfactorily. In other words, the basic model that we start from is one of principals and agents (Lupia 2003; Miller 2005). The role of institutions in these relationships is to help to minimise ‘agency loss’. Lupia (2003: 35) defines agency loss as ‘the difference between the actual consequence of delegation and what the consequence would have been had the agent been “perfect”’, with perfection conceived as the agent doing what the principal itself would have done, given unlimited information and resources.

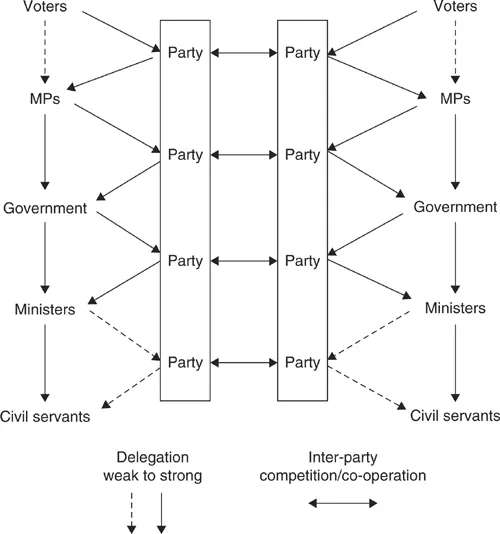

Furthermore, we envisage the process of delegation in parliamentary democracy as, in practice, following multiple tracks or channels. Bergman and Strøm (2004a, 2011) outline three channels within which delegation and accountability is conducted. One of these channels is the constitutional one, in which voters delegate to parliamentarians, who delegate to a prime minister, who delegates to ministers, who delegate to civil servants. In most of the stages, parties play a vital role in allowing delegation and accountability to proceed effectively. Indeed, this role is so vital that in addition to the formal, constitutional channel, parties can be seen as comprising their own separate channel of delegation. This party channel is the one that primarily interests us.

The third channel is what Bergman and Strøm (2004a, 2011) call external constraints, that is, mechanisms that give principals at different levels the chance to monitor or sanction their agents in ways that go beyond or circumvent those mechanisms that normally structure the delegation relationship. External constraints include such institutions as referendums, constitutional courts, independent executive agencies and – of particular interest to us – supranational authority, such as the European Union. Parties tend not to be much involved in external constraints – although, as we will see later in this chapter, their involvement in European integration is said to be increasing.

This balance between the weight that any polity places on these three channels is not straightforward or stable. In fact, the model of democratic delegation that has traditionally been associated with parliamentarism in general, and the Westminster style of parliamentarism in particular, may well be seriously compromised by the growing importance of external constraints, especially those exercised from a supranational level of decision-making. Our research project was fired by our interest in the impact of external constraints that the EU imposes.

Earlier research has investigated the impact of European integration on the constitutional track. We concentrate on the impact of European integration on the party track. Our research question can then be summarised as: how effectively does intra-party delegation occur within Nordic political parties? We seek to answer this question through a comparison across parties and between two levels of operation, the national and the European.

The rest of this introductory chapter unfolds as follows. First, we peruse the research context. We review existing literature on parties, democracy and European integration, framed by those three channels of delegation and accountability. Our discussion emphasises contributions that have special relevance to the Nordic states. During this review, the contribution of our project to this literature should become clearer. In the following section, a further, methodological rationale for our project is offered. Finally, we outline the remaining chapters in this book, in which our specific analytical model and expectations, our country studies and our conclusions are presented in turn.

Political parties and democracy: The constitutional channel

Parties offer a mechanism for aspiring political leaders to pursue their goals, through minimising transaction costs and resolving collective-action problems (Müller 2000: 312–17). In so doing, parties also offer citizens a means of holding their political elites to account in the constitutional channel.

By aligning themselves under a common party banner prior to an election, and by signing up to a common party platform, individual candidates can make more credible promises to electors about what they might achieve in the post-election parliament. With their personal reputations bound to that of the party, individual parliamentarians are then forced to share responsibility for the action of the executives affiliated to that party if and when these executives get the chance to govern.1 Parties thus make the process of selecting a collective decision-making body, the parliament, one in which voters can exercise a reasonably informed choice. For one thing, they can make a judgement about parliamentarians’ previous actions. At the same time, they estimate parliamentarians’ likely future behaviour, thanks to the collective interest of these parliamentarians and their aspiring successors within the party in preserving its reputation among voters. As Müller, Bergman and Strøm (2003: 19) put it, parties ‘seek to remain in business well beyond the terms of individual politicians, and hence do their best to make incumbents with discrete ambition (that is, ambition that does not extend beyond their current term of office) behave as if they would face the electorate again’ (see also Brennan and Hamlin 2000: 191–2; Müller 2000: 325).

Further down the chain of delegation, parties have still more to offer. They serve to simplify the process of bargaining between MPs about policy output by reducing transaction costs (Cox and McCubbins 1993; Lindberg, Rasmussen and Wantjen 2008b: 1111–2; Thies 2000). Above all, they structure MPs’ choice of their own agent – that is, the prime minister. The prime minister’s delegation of tasks to individual ministers is also strongly influenced, if not always entirely constrained, by party affiliation. Only in the final step in the constitutional channel, from ministers to civil servants, is the role of party usually seen, at least formally, as less welcome (Müller 2000: 311).

In sum, the singular chain of delegation in a parliamentary system – from voters to MPs to prime minister to line ministers to civil servants – helps to align the preferences of many of those who hold public office, so that policy can be implemented with minimal obstruction from other actors and institutions (Bergman and Strøm 2004: 98; also Strøm, Müller and Bergman 2006).

In presidential systems, the different branches of the state – executive, legislative, judicial – are designed to check and balance each other. In the language of our model, the system features strong external constraints. While parties are far from irrelevant under presidentialism (cf. Aldrich 1995), the individual character of many public offices (not least the presidency itself), plus the deliberately engineered tension between those offices, serve to make cohesive, organised parties less central to political competition than they are in parliamentary systems.

A distinguishing feature of parliamentarism, by contrast, is that the executive, rather than being by checked by the legislature, is connected to it via an accountability relationship and reflects in some way the distribution of preferences within parliament.2 A parliamentary election is thus, indirectly but fundamentally, about government formation. This provides the party with an incentive to present to the electorate a clear set of pre-election pledges about how it would like to govern, and to discipline its affiliated candidates if they stray from those pledges. At the following election, the governing party’s candidates have no one else to blame for its policy failures in government when they stand for re-election. Alternatively, and more optimistically, they need not share with other public actors the glory for policy successes. Parties thus provide what Jones and Hudson (1998: 185) describe as an ‘implicit contract’ between the voters and the elected representatives.

In addition to this electoral connection, most prime ministers in parliamentary systems, though not all, enjoy two further powers. First, they can make particular parliamentary votes issues of confidence. Second, they can, largely at their own discretion, dissolve parliament and call a fresh election. Both these powers add further incentives for party cohesion and discipline (Strøm 2003: 69–70). So too does the fact that ministerial recruitment often, though far from always, draws from parties’ parliamentary groups, which gives ambitious MPs reason to avoid upsetting their party leader.

Political parties and democracy: The party channel

Clearly, parties are indispensable for making the public institutions of parliamentary democracy work. But parties do more than just reduce the ‘agency loss’, or sub-optimal delegation, that occurs via the constitutional channel. As mentioned above, they are in themselves also an additional means of delegating power and of holding accountable those to whom power is delegated. If citizens choose to engage in a party as members, and that party has any sort of internally democratic structure, then the party’s leadership group can be understood as the agents of the membership (Müller 2000: 319). Members of a party’s leadership can be sanctioned by its members, even if they have also been elected in public elections and thus concurrently hold public office.

Figure 1.1 The role of political parties in the chain of delegation and accountability under parliamentarism

Source: Müller (2000); Ström (2003: 68).

The possibility of recall by their party is thus a serious discipline on the behaviour of elected politicians under parliamentarism, even of those holding the very highest public positions. After all, nearly all members of these elites are party figures; prime ministers are usually the leaders of their parties. Party recall of a sitting prime minister might only happen rarely, but two British examples – Margaret Thatcher in 1991 and, less spectacularly, Tony Blair in 2007 – showed clearly that it can.

Figure 1.1 summarises parties’ roles in the first two channels of delegation and accountability. While parties’ role in the constitutional chain has been the subject of much recent scholarly attention, the process of delegation of accountability within parties has been neglected in comparison. We seek to contribute to righting this balance.

Parties and democracy: The EU as external constraint

In this section, we review some of the scholarly literature on the impact of European integration on national democracy in the EU’s member states. Before we start that properly, however, we should mention the position of our work in relation to another growing body of research, on ‘Europeanisation’.

The capacity of the term ‘Europeanisation’ to exasperate has grown in step with the literature on it. The main problem is the variety of definitions (Olsen 2002: 923–43). In recent years, most major studies of Europeanisation, though far from all, have focused on how the EU affects its member states. ‘Europe’ is no longer the dependent variable, influenced by the various ways (‘policy styles’) in which the states build it; instead it has become the independent variable, a way of explaining outcomes at national or sub-national level (Anderson 2002: 796).

Our study comprises a comparison of intra-party relations at national and EU levels. While it might make sense to talk in some branches of political science about more or less Europeanisation (for example, policy studies in which there are clear EU norms around which member states may, or may not, ‘Europeanise’), we doubt that this is appropriate in party research. Although political parties are now incorporated into quite big parts of the EU’s operation (see below), there is as yet no European model of party around which national parties might converge. Still, we are obviously very interested in the effect of the EU on national democracy. Given our position, explained above, that parties are essential to democracy, especially of the parliamentary variety, we clearly need to take account of the ways in which scholars have considered the concept of democracy in the EU. This is what we consider in the following paragraphs.

The democratic deficit

In a major recent survey of delegation and accountability in West European democracies, one of the authors acknowledges that the normative model of parliamentarism assumes that ‘[t]he political community is bounded and given’ (Strøm 2003: 68). But, he also acknowledges, this no longer reflects reality (if it ever did). Before the launch of the European Communities in the 1950s, and their development into the European Union in the 1990s, sovereign European states were the highest form of political authority. That authority was located within and delimited by national borders. The states were constrained in their behaviour by impersonal, global economic forces and by the potential reaction of other states under the prevailing international regime. These days there are actions in a number of policy fields – especially trade, industrial, competition, labour-market and monetary policy – that they are prohibited from taking by legal restrictions imposed by the Union.

Arguably, this constitutes a democratic problem (Holzhacker and Albæk 2007: 2). As was mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, the nature of this problem was made more acute by the introduction of qualified majority voting in the Council of Ministers. Majority voting left national representatives potentially non-responsible, and thus unaccountable, for policy outcomes that affect the ultimate principals, t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Authors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Parties and the Challenge of Multi-Level Politics

- 2 Principals, Agents, Parties and the EU

- 3 Denmark: Party Agents on Tight Leashes

- 4 Finland: From Permissive Consensus to Angry Birds?

- 5 Norway: Strong yet Marginalised Parties

- 6 Sweden: Power to the Parliamentarians?

- 7 Conclusions: Nordic Political Parties, European Union and the Challenge of Delegation

- Notes

- References

- Index