eBook - ePub

Globalization and Development

Why East Asia Surged Ahead and Latin America Fell Behind

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Comparing the experience of East Asia and Latin America since the mid-1970s, Elson identifies the key internal factors common to each region which have allowed East Asia to take advantage of the trade, financial, and technological impact of a more globalized economy to support its development, while Latin America has not.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Globalization and Development by Anthony Elson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction—Globalization and Economic Divergence

In recent years, and in particular in the wake of the global financial crisis, there has been much commentary about the shifting balance of economic power in the global system from the advanced countries on both sides of the North Atlantic to the rising powers of East Asia centered around China in the Asia-Pacific region. This shift reflects one dramatic result of economic globalization that has allowed certain countries, in particular the new industrializing economies of East Asia, to enter into a process of convergence and catch-up with the advanced countries of North America and Western Europe. This pattern of development has been underway since the middle of the past century, but it has intensified since around 1980.

The rise of East Asia reflects the remarkable ability of this region to have taken advantage of the dramatic growth in global trade and financial flows, which have been supported by major improvements in transport and communications, as well as the transfer and mastery of technology from the advanced countries through imports, foreign direct investment, and licensing agreements. This pattern of globalization confirms one strong view about globalization advanced by leading economic academics, such as Robert Lucas, that points to an inevitable and gradual process of economic convergence in response to the integrating forces of trade, finance, and technological change.1

However, economic and financial globalization has also produced a broader pattern of economic divergence, which differs from the convergence scenario above, when one considers the performance of national economies across all the regions of the globe. Within this universe, one can find disparities in income per capita in the first decade of the twenty-first century of more than 100 to 1 between the richest and poorest economies, which have been growing over time. On the basis of the long-term historical data of Angus Maddison, which measure income per capita in constant dollars across countries on a purchasing power parity basis, economic divergence among countries has expanded sharply since the beginning of the nineteenth century.2 At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the disparity between the richest and poorest countries of the world was only around 5 to 1. By 1870, this ratio had increased to 8 to 1. At the dawn of the modern era in 1950, the disparity had reached around 30 to 1, which then rose to more than 100 to 1 in 2010, the last date for which national income estimates exist in the Maddison database. Within this long time span stretching from the beginning of the nineteenth century, one can also see a long U-shaped trajectory for the dominant position of China and India in global manufacturing output, which was eclipsed by the start of the Industrial Revolution in Western Europe in the early part of the nineteenth century, and is now in a phase of gradual resurgence with the dawn of the twenty-first century.3

The great divergence of income per capita that has emerged among countries, in particular during the second half of the twentieth century, has given rise to an enormous inequality of income that has been estimated in terms of Gini coefficients at around 65 percent toward the end of the past century, which is far greater than the measure of inequality in any particular country. According to the work of Branko Milanovic, around 85 percent of the measure of global income inequality at the beginning of the twenty-first century can be explained by differences in mean incomes across countries, with the remainder due to differences in meanincome within countries.4 The reverse was true at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the early part of the nineteenth century.

The Big Reversal

Understanding the factors that can account for these patterns of economic convergence and divergence within the global economy is one of the major challenges of economics, and social science more generally. As a contribution to this inquiry, the present book attempts to explain the causes for this outcome of globalization by examining a particular example of economic convergence and divergence that is reflected in the comparative economic development of East Asia and Latin America since the middle of the past century.

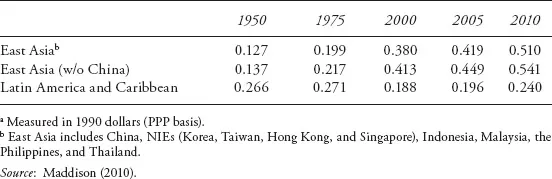

Table 1.1 Real GDP per capita in relation to that of the United Statesa

Since 1950 these two regions have followed very different economic trajectories. At the beginning of the period, Latin America was the most important region in the developing world in terms of per capita income and the size of its manufacturing sector, while East Asia was relatively undeveloped. By the end of the past century, however, the relative positions of East Asia and Latin America (in terms of relative income per capita vis-à-vis the United States) had been reversed (Table 1.1). In fact, during a 30-year period (from 1975 to 2005), Latin America fell steadily behind the income level of the United States, while East Asia surged ahead.

This big reversal in the economic fortunes of the two regions is one of the most dramatic examples of “catching-up” and “falling behind” during the second half of the twentieth century.

Most of this reversal occurred after 1975, when Latin America went into a period of relative stagnation, while East Asia entered a period of sustained, rapid growth. In the case of Latin America, this outcome has been particularly troubling in view of the substantial economic reforms that have been implemented in the region since the mid-1980s, largely consistent with the precepts of the so-called Washington Consensus.5 That framework, which was defined at the end of the 1980s, attempted to codify the lessons of economic policy among successful developing countries, in terms of advocating a less interventionist stance on the part of government policy while giving greater weight to the role of market forces and global integration in guiding economic activity. During the past two decades, there has been much debate on the appropriateness of the ten guiding principles of economic policy embodied in that consensus, which has tended to emphasize the factors or considerations that were missing from the original list.6 In particular, there has been a reassessment of the role of government in the development process, which calls for a more balanced view of government policy and market forces as complements, rather than substitutes, in development policy. This evolution of thought about the conflicting or complementary roles of the state and the market in development policy will be examined in more detail in chapters 3 and 8.

Contrary to the Lucasian or neoclassical view of economic development referred to earlier, which argues that economic convergence is a relatively spontaneous process for countries once they adopt policies of economic and financial liberalization (consistent with the principles of the Washington Consensus) that make them responsive to the integrating forces of globalization, this book advances an alternative perspective based on the comparative experience of East Asia and Latin America. This alternative view of the development process identifies, on the one hand, the unique role that government economic policies can play in allowing countries to take advantage of global trends through a careful process of internal and external liberalization and, on the other hand, the forces of globalization as reflected in the operations of multinational corporations and global financial institutions that have benefitted from major improvements in transport and communication.

In this connection, it is important to recognize that, over the broad sweep of history, globalization has been driven by recurring waves of technological revolutions, which have facilitated international trade and investment and promoted a more interdependent international economic system. During the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, global integration was driven by the combined forces of the telegraph, which made long-distance communication possible, and the steam engine that powered steam ships and locomotives, which made possible the separation of industry and commerce from the same location.7 One can observe a strong inverse correlation between the growth of international trade and the pronounced decline in transportation costs during the second half of the nineteenth century, which sparked its expansion. Likewise, during the last quarter of the twentieth century, a second technological revolution associated with electronic information and communications technology or ICT has had a profound effect on business management and production, which has spurred the emergence of global production networks and the fragmenting of production and trade across different national boundaries.8 In addition, global trade has been further propelled by the containerization of freight transport and the construction of large containerships.9

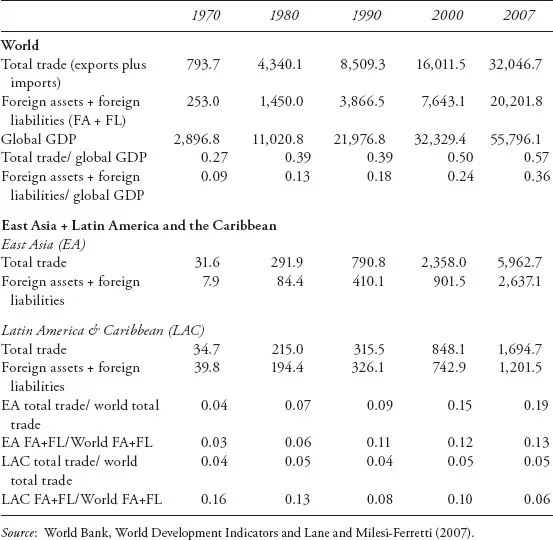

Over the past 30 years or so, a rising share of international trade and investment has been dominated by the activities of large multinational or transnational corporations, which at the turn of the past century accounted directly for around one-third of global trade in the form of intra-firm trade, and roughly two-thirds of global trade in transactions with other entities.10 According to recent UNCTAD estimates, an even higher share of global trade in exports (around 80 percent) is linked to the global production networks managed by multinational corporations as either intra-firm or arms-length trade. The flows of global trade accelerated sharply during the second half of the twentieth century, and in particular since the 1970s. The value of exports and imports as a percent of global GDP has more than doubled from around 27 percent in 1970 to 57 percent in 2007 (Table 1.2). At the same time, financial globalization, as measured by the ratio of foreign assets and liabilities as a share of global GDP, has expanded by a factor of 4 between 1970 and 2007. Within these global trends, it is readily apparent that East Asia has achieved a much greater degree of integration into the global economy than Latin America.

Table 1.2 Global trade and investment (in US$ billions or percent, as indicated)

Most of the expansion in economic and financial globalization has been managed through large private financial and nonfinancial multinational corporations operating among the advanced countries. However, since the mid-1980s, a growing share of global financial flows have been directed to low- and middle-income countries, driven largely by an increase in foreign direct investment, which in many cases has been linked to the development of export trade capacity in the recipient countries.11 In the light of these developments, the achievement of successful economic development by low-income countries in the twenty-first century depends to a large extent on the degree to which a country is able to take advantage of these forces of globalization through an appropriate set of policies focused on its internal and external development. The comparative analysis of East Asian and Latin American economic development, especially during the last quarter of the twentieth century, can provide some insight into what policies might be appropriate for taking advantage of these new forces of globalization. In addition, this analysis should provide some insight into the problem of the “middle income trap” that has been identified with a number of countries, in particular in Latin America, that have experienced a marked slowdown in the pace of their economic growth on reaching a per capita income level in real purchasing power parity (PPP) terms of around US$7,000. By contrast, East Asia has emerged as one of the few regions in which countries such as Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan have escaped that trap and have moved into advanced country status. Other countries in the region, in particular China, seem to be following the pattern of the four aforementioned countries.

In the light of the above observations and the complexity of the development process, this book attempts to understand the comparative economic development of East Asia and Latin America within an interdisciplinary framework that combines an analysis of economic issues relevant to the development process with historical, institutional, and political economy perspectives. In this connection, the study draws on a rich body of literature that has focused on one or more of these perspectives in a strictly regional context. However, few, if any, studies have tried to provide a unified framework for understanding the regional economic divergence between East Asia and Latin America from a multidimensional perspective.12

The Recent Experience of Economic Development in an Age of Globalization

In trying to understand the problems of economic divergence and convergence in an age of globalization, it is important to recognize that the process of economic growth outside the advanced countries since the middle of the past century has not been in conformity with the stylized results of standard models of economic growth. According to the neoclassical theory of economic growth, which guided the predictions associated with scholars such as Robert Lucas, economic development is a relatively steady, linear process of growth in real GDP per capita, which is roughly uniform over space and time, as countries expand their investment and take advantage of the diffusion of technological change. The US economy comes closest to exhibiting this long-run pattern of growth, through which sustained increases in income per capita were brought about by the steady accumulation of capital (both physical and human) and the continued application of new technology generated by innovation and research and development to foster improvements in productivity. Within this framework, poor countries with lower stocks of capital and a higher marginal productivity of capital than rich ones will achieve a convergence of income per capita with the advanced countries at a steady rate through high levels of investment and the absorption of foreign technology, as long as high rates of savings and low population growth are maintained. This vision of the growth process gave rise to the vision of a “steady state” as codified early on by Nicholas Kaldor in his six stylized facts of growth.13

What one observes in the pattern of economic growth of nations since the middle of the past century, however, is markedly different from the stylized results of the standard growth model described in the previous paragraph. As noted earlier, economic convergence is conditional, not absolute; and economic growth is not a steady, continuous linear process, which is spatially homogeneous within and across countries. Rather, it has tended to be lumpy in space and time, and concentrated in certain regions of the globe. Countries in the process of economic development experience spurts of economic growth, which are associated with a structural shift in employment and production away from primary a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction—Globalization and Economic Divergence

- 2 The Economic Development of East Asia and Latin America in Comparative Perspective

- 3 Changing Paradigms in Development Economics

- 4 Initial Conditions for the Postwar Development of East Asia and Latin America

- 5 Economic Policy Choices—Macroeconomic and Financial Stability

- 6 Economic Policy Choices—Savings, Investment, and Industrialization

- 7 The Role of Institutions and Governance

- 8 The Political Economy Factor in Comparative Economic Development

- 9 Three Cross-Regional Case Studies

- 10 Conclusions and Lessons for Development Policy

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index