- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Rhys Matters, the first collection of essays focusing on Rhys's writing in over twenty years, encounters her oeuvre from multiple disciplinary perspectives and appreciates the interventions in modernism, postcolonial studies, Caribbean studies, and women's and gender studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rhys Matters by M. Wilson, K. Johnson, M. Wilson,K. Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Alternatives and Alterities: Market, Time, Language

CHAPTER 1

Menu, Memento, Souvenir: Suffering and Social Imagination in Good Morning, Midnight

Its subjective manner, a variant of the stream of consciousness, is anything but fresh nowadays and is more than commonly monotonous where the subject is forever stretched on a bed of live coals.

—“The Lost Years,” review of Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight, Times Literary Supplement, April 22, 1939

Spare and belated in her writing style, Jean Rhys is an also-ran in the story of literary modernism between the wars. Solipsistic and suffering in content, Rhys’s works vex efforts at rehabilitation by contemporary critics. Too little, too late, too much: so Jean Rhys’s 1930s novels drop off the map, even after decades of feminist recuperation and canon questioning. The pained story of me (the story of Rhys’s lost innocence, lost family, and little money) that drives her 1930s novels pulls on her style, making something tricky, discordant, and surreal easily seem “monotonous” and overblown with self-pity. This chapter is such an effort at rehabilitation, or as I prefer to think of it, exegesis: to my mind, we critics must ever explain Rhys’s art of suffering, both how her style is complex and timely and how her narratives of personal suffering are at the same time narratives of social suffering. We can, as the novels sometimes do, declare the story of Rhys’s me as a story of we (of women, of white Creoles, of modern subjects), but more importantly, illustrate and instruct in the fine articulations of the social, of publics and worlds, in Rhys’s carefully crafted self-centered me. Such efforts bring out not only the tricky aesthetics but also the tricky politics of Rhys’s writing, its confounding admixture of progressive and conservative thinking. Protest, critique, and collective-mindedness compete with cynicism, consumerism, and yes, self-centeredness in Rhys’s writing, rendering her novels difficult if not disappointing as representations of the down-and-out 1930s. So much is wrong with the world in these novels, so much wrong that we share, yet little can be done other than make the most of what you or I can get; we suffer in kind, that is, but must fend for ourselves alone. Rhys’s early novels pointedly stop short of transformative social vision but do not fail for this reason.1 They express limits we must work with to best explicate both the artfulness and historical significance of her social imagination.

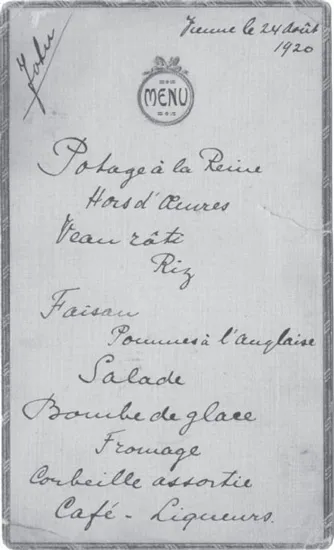

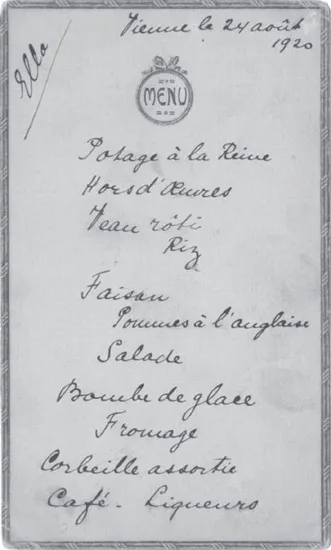

This chapter aims to explain the art of Rhys’s social imagination in the instance of her 1939 Good Morning, Midnight, and more particularly, through a comparison of objects from the writer’s archive to an object represented in that novel—through a comparison of two café menus, one from a dinner given in honor of Rhys’s 30th birthday, preserved in the McFarlin Library at the University of Tulsa, and the other read by the novel’s protagonist, Sasha Jansen, early on in her narrative. These menus token economic vulnerability in different ways, the first showing how Rhys remembered the insecurity of living on “the market” in her own life, of living high on money produced by a mysterious system of exchange (what was in fact the black market of currency exchange in post-WWI Europe) and the second showing how women, specifically poor women, manage the market as a system of exchange that structures the world and values them for their exchangeability as things. The different work these menus perform is a difference captured by the terms “memento” and “souvenir,” suggesting as they do a spectrum of diverse meaning and circumstances of collection, from personal and private at one end (memento, an object repurposed for the recalling of one’s own feeling or doing at a particular time and place) to social and public at the other (souvenir, an object made expressly for the purpose of recalling a time and place that is recognizable to and experienced by other people as well as oneself). The comparison of these menus brings into view how astonishingly Rhys turned personal memory into social imagination, how Rhys worked her remembrance of one lady’s hard times—her autobiographical own and, differently, her fictional protagonist’s—into an innovatively assembled meditation on women’s economic vulnerability. The comparison brings clearly into view Rhys’s artful critique, her complex representation of how women are both pressured by and complicit in a “market” system, a system that also and inevitably zeroes out those who use it to get by. Just as important, the comparison brings into view both the transformative ambitions and the matter-of-fact limits that reveal Rhys as anything but monotonous and altogether illuminating of a larger world in her day, that show how Rhys matters now as she should have then (figures 1.1 and 1.2).

Figure 1.1 “John” menu from Jean Rhys’s 30th birthday dinner.

The menu preserved in the Rhys archives is an artifact of the dinner given in honor of the writer’s 30th birthday at a café in Vienna. In fact, two copies of the menu are preserved, one addressed to Ella (Jean Rhys) and the other addressed to John (the name by which Rhys called her husband Jean Lenglet). They are small, bordered cards marked “menu” and inscribed with the courses of the dinner, dated August 24, 1920 (see figures). According to Rhys’s biographer Carole Angier, the dinner was a gift from Jean Lenglet’s employers, a Japanese delegation to the League of Nations, for whom he worked as a translator; Angier describes another version of the menu that is signed on the back by the delegation and the Lenglets’ housemate, much like the one Rhys describes in After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie (116, 179; see also footnote 8). The two birthday menus, which are preserved in the premier archive of the writer’s papers at Tulsa, are held in a rather small file of “personal papers”: other items include identity documents, a casino ticket, a list of girls’ clothing, materials regarding her infant son’s death, as well as items personal to Rhys’s husbands and family members. The menus’ duplication—what we could understand as their double preservation—suggests that they were extremely valuable to her as mementos, that she used them as a way of understanding herself from past to present. In their notation of dinner courses of what was surely an excellent meal (hors d’oeuvres, roast veal, pheasant, fruits, ices, liqueurs), the menus remember a self that consumes purely, conspicuously, and extraordinarily, a self that does more than just survive. The menus document a gathering of friends and gift of her husband’s employers, and so remember a self that was not solitary, a self that had a place within civil society as spouse and moreover as spouse to an employee of a League of Nations delegation. Finally, and just as significantly, because marking the 30th birthday, the menus remember a self that was (by convention) only now passing her prime. Remembering so much and so particularly what Rhys characters so often want—to consume thoughtfully and elegantly, to be wiser but not so much older, to feel right in a crowd rather than odd and alien—the menus are ideal mementos. Not only do the menus do the temporal work of longing, reminding of distance from the past at the same time as they carry the past (in Susan Stewart’s phrasing), but they also do the figural work of longing, presenting precisely the self that Rhys often tells us she desired to be.

Figure 1.2 “Ella” menu from Jean Rhys’s 30th birthday dinner.

Carole Angier tells us that the period of Rhys’s life from which the menus originate—when she lived in Vienna, from early 1920 to summer 1921—was a period that she “didn’t like to talk about.” Angier quotes Rhys as saying, “I am determined not to write about Vienna and what happened there” (116), and her autobiography Smile Please makes only passing allusion to the period. Rhys did write about it in her fiction (principally in the short story “Vienne” and briefly in “Temps Perdi”), but I want to take her at her word—that she did not want to remember this period by writing about it—in order to think about how this menu remembers Vienna in a different way, in a way Rhys found preferable, if not, perhaps, just right. Angier says in Jean Rhys: Life and Work that Rhys didn’t want to write about the period because it would ultimately impugn her husband, who was engaged in black market dealings, selling foreign currency, and ultimately losing money not his own. And Angier goes on to speculate that writing about the period would require Rhys to “relive one of her greatest disappointments,” that disappointment being the end of a period of easy living, of servants, nice dresses, and well-maintained beauty (116). I would like to shift the emphasis in Angier’s speculation, to speculate that what was so psychically difficult about this period is not its actual end, its having come to an end, but rather its always having been ending, its profound instability as a high and giddy time, its feeling of ground inevitably giving way to nothing. This feeling of the time and of time is conveyed by the term Rhys herself used in fictionalizing the latter days of the period, “The Spending Phase” (“Vienne,” LB 2212). Not the buying or the getting or even the consuming phase, but the squandering, the giving-away-what-you-have phase; the phase that is defined by an act of what will inevitably bring its end. The profound instability was exacerbated by the feeling, I would further argue, that this ground was not grounded, that its inflow was as unsettling as its outflow. For the household income that allowed Rhys’s extravagant consumption in Vienna derived from Lenglet’s currency dealings on the black market—from making money by exchanging money and without any actual commodity coming into play—rather than from Lenglet’s work as a translator for the League of Nations delegation. The household was based on a market altogether abstract (even if conducted through actual printed money rather than data networks), and altogether mysterious for being illegal: Lenglet little explained the money’s underground source to Rhys, and she made little inquiry (Angier 116–120). Finally, the Lenglets’ wealth must have felt profoundly unreal because it came, specifically, in post-WWI Vienna: there and then presented a situation of shocking want and privation, where “real incomes [had] declined by 60–90 percent … as prices skyrocketed,” a city William Beveridge had found “ ‘literally starving’ ” during a diplomatic visit (Thane 147). Rhys indeed uses this situation in “Vienne” to set off the protagonist’s wealth as strange and strange-feeling.

Though dating from her first summer in the city, and so preceding “The Spending Phase” proper, the menus are certainly “about Vienna and what happened there,” a memento of those high and prosperous days that culminated in the luxury and unease of mysterious and sudden wealth, and that passed against a background of dire poverty and upheaval. “The gay round of entertainment reached its peak on her thirtieth birthday in August,” Angier writes of the dinner gathering (116). In her short story “Vienne,” Rhys conveys the sense of giddiness she experienced in Vienna: “I was cracky with joy of life that summer of 1921.” She conveys her sense of the mysteriousness of income from “the change” and the awful precariousness of possessing the “great god money,” and she even imagines the Spending Phase to its bleak end (CSS 101, 106).3 But I contend that the writing doesn’t recall the instability of the Vienna period as nicely to the recollecting Rhys as do these little birthday menus.

The archived birthday menus give material form to something that would otherwise leave no trace—to food that was consumed, to ambience and service, to cosmopolitan gathering and sociability. They make something transitory and largely sensual into something tangible, arguably remembering one of the highest days of the Vienna period less the feeling of dissipation. These mementos, at least, have been preserved. More important, however, the birthday menus recall a signal event of those days in the form of sentimental objects that recollect the fact of a gift. Kept by Rhys over a long and far-flung life and in duplicate, we can presume that the menus are objects imbued with sentimental value—that their loss would have been felt by her, that keeping two perhaps guarded against such a loss, that they carried precious emotional meaning. Bracketing the issue of their current disposition within a celebrated writer’s archive and their at least theoretical place on the collector’s market, we can further say that the menus’ entire value is sentimental: they are, after all, just pieces of paper dirtied with age, describing a dinner no longer available. As anthropologists have theorized, such sentimental objects that carry no material value (as they might in some other forms, such as jewelry) defy economic understandings of value based in use or money.4 For this reason, we can say that the menus betoken a system alternative to that of the “market,” and we can consider that the menus ideationally removed their holder from circuits of exchange. And as objects that recollect the fact of a birthday gift, the menus figure a system alternative to the market in an additional way: in the definitional ideal of the anthropological understanding of “the gift,” a gift represents an object not exchanged, a thing that cannot be spent or even traded. The menu described by Angier, imprinted with signatures, not only recalls the fact of a gift but also bears the very trace of the gift-givers; that version of the menu renders material the anthropological idea of the gift, famously outlined in the works of Marcel Mauss, that the gift always carries the giver with it (it is “inalienable”). As remembering a gift predominantly from the employers of Lenglet as a translator, the menus represent those who stood for the household’s legitimate and legible sources of income rather than the system of “the change” that bankrolled Rhys’s high living. For all these reasons, the menus alternatively imagine the situation of Rhys’s Vienna days, memorializing her life there as at a remove from the market.

Certainly, the menus preferably captured Vienna for Rhys’s remembrance because they are a selection—because they memorialized a securely happy day from the period, early on, when Rhys was not yet riding a mysterious financial boom, when perhaps income and expenditure befitted a diplomatic secretary’s salary. They speak not of the starvation that the Viennese experienced but of exquisite, even excessive, consumption of the victors. But the menus work not merely as a selective recollection of the period: as principal mementos of her stay there (the other being a French-issued visa for travel to Vienna and a postcard sent to Rhys bearing the signatures of the Japanese delegation), we can surmise that the menus represent Vienna more wholly, that they stood for her memory of Vienna in more than just one of its moments and one of its moods. They call up into the present the spending of money, spending of precious youth, and what must have been a “cracky” day of contentment alloyed with unease, and yet render these events not only distant in time (as do mementos generally, as memory objects that both carry the past and create distance from the past) but also, and more importantly, distant in feeling. Nostalgia, patently: the memento remembers ideally, remembers contentment without alloy and pleasure that gratifies rather than giddies. It tells the past in ways that must have salved the wounds of personal disappointment, of disappearing wealth and forfeited ease. But in its form as a sentimental object that remembers a gift, this nostalgia tells us of more than personal meaning. It tells the past in ways that salve the wounds of modernity, that refigure the world as structured not through capitalism and its market, but through an alternative and reparative economy of the gift. Obliquely but severally, it tells of the profound instability of living on the postwar world market in its remembrance of living off of it.

Rhys’s birthday menus show how such personal and sentimental objects make social meaning in their material form and in the figures that come with them—in the form of a menu and in the figures of a gift and its givers, what are figures of inalienability put in place of spending. (Fittingly, and as we shall now see, Rhys uses a different menu form in the novel Good Morning, Midnight, a menu with prices listed, to create a situation wholly unlike that of her birthday gift.) Even such objects—privately collected, preserved and unaltered—make clear both that Rhys arranged her life artfully and that her own story is at the same time representative of more than just one. Remembering the modern world within an alternative system to that of market, the objects challenge the self-centered single story that Rhys can seem only to speak. It becomes legible as a document of social history, showing Rhys’s own biographical story to indicate a broader story of postwar Europe. Turning to Rhys’s creative writing, and in particular to her writing of a similar object, to a café menu in Good Morning, Midnight, we can see an even greater challenge to the simplistic self-centering of Rhys, not only how artfully and surprisingly Rhys worked autobiographical material (like these menus) into fiction, but also how ambitiously and complexly her fiction represents one narrator as so many others who suffer in the modern world.

The menu featured in Good Morning, Midnight appears early on in the novel, in the scene set at the “Pig and Lily” (aka Pecanelli’s) café. The Pig and Lily scene is a tour de force, a surreal staging of Sasha as English lady tourist in the Dutch-Javanese café, as both perfectly belonging and not belonging to the European metropolis. It offers a concise vision of the unjust calculus of race and money that characterizes an empire. Just as important, the scene offers a thoroughly ironic demonstration of Sasha’s feeling of economic well-being, exhibiting for us the profound vulnerability of aging women to destitution. It does so, notably, through her inspection of a menu that develops the novel’s trope of market economy.

Dominant in the novel and integral to the work of the Pig and Lily menu, the trope of market economy bears explanation: Good Morning, Midnight figures a system that determines some persons as valuable and others as worthless, and that renders almost every interaction into an exchange. It is a system in which aging women, like the protagonist Sasha Jansen, are most vulnerable to abject poverty, figuratively and literally zeroed out by it. “Society” declared a young Sasha, being an “inefficient,” “slow,” and “slightly damaged” woman, to have a “market value” of 400 francs a month in payment for work (GMM 29). Youth, coming with some capacity to labor and desirable looks, explicitly gave Sasha a modicum of worth in the world, but these features are void in the “old” narrating Sasha of the novel’s present. Sasha is wife without husband and mother without child (as well as prodigal niece); Sasha is useless in just the ways women were thought to have (exchange) value at the time, a consequence of being not only short on attraction and charm, but also without practical or affective ability to sustain home, household, or family. Destitute of family and youthful desirability, she grieves and pays emotionally, but the novel additionally suggests that because of this destitution she must pay cash; it suggests that, because she is personally void within the “Society” ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction: Rhys Matters?

- Part I: Alternatives and Alterities: Market, Time, Language

- Part II: Being and Believing: Judeo-Christian Influences and Identities

- Part III: The Location of Identity: Writing Space and Place

- Part IV: Pleasure, Power, Happiness

- Notes on Contributors

- Bibliography

- Index