eBook - ePub

The Changing Faces of Childhood Cancer

Clinical and Cultural Visions since 1940

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Changing Faces of Childhood Cancer

Clinical and Cultural Visions since 1940

About this book

This book traces the development of British answers to the problem of childhood cancer. The establishment of the NHS and better training for paediatricians, meant children were given access to experimental chemotherapy, sending cure rates soaring. Children with cancer were thrust into the spotlight as individuals' stories of hope hit the headlines.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Changing Faces of Childhood Cancer by Joanna Baines,Kenneth A. Loparo,Emm Barnes Johnstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Childhood Cancer: A Disease Apart

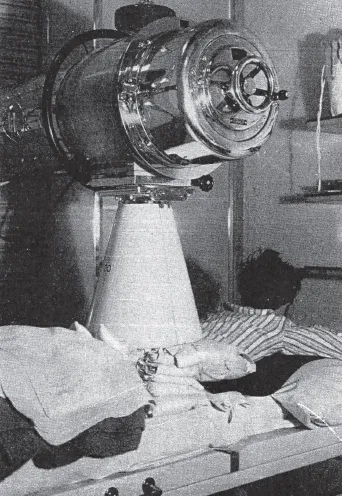

A boy in his early teens lies on a bed under a 200-kV X-ray machine, preparing to receive his daily dose of radiation, treatment for the metastases spreading from a tumour in his testicles. The radiation is being administered through a large circular applicator, ensuring even distribution over the whole abdomen in the hopes of catching every malignant cell in the region; the area around the applicator is shielded with lead and rubber to protect other tissues. He receives daily blood tests to monitor the effect of the treatment: a depleted number of lymphocytes – a type of white blood cell – indicates the treatment is taking effect, but if the count drops too far treatment will have to stop, as the risk of infection becomes too high. He will also be monitored for radiation sickness, the initial doses he receives being low, then increased until his point of tolerance is reached. The treatment will take about three weeks. During this time, he will be an inpatient in the Christie Hospital in Manchester, receiving his daily radiotherapy at the associated Holt Radium Institute (Figure 1.1).1

This boy’s chances of survival were as good as they could be anywhere: the large new cancer hospital in Manchester was renowned worldwide for its innovative and successful application of radiotherapy in the treatment of metastatic cancers. The therapy was intended to be curative – that is, the doctors managing his care subjected him to this long and dangerous course of radiation because his kind of tumour was known to respond strongly to radiation and to be, on occasion, totally curable. Unfortunately, the research paper in which his treatment was described, published in 1940, tells us little about the long-term effect of the regime on his general health, his state of mind, or his survival. Nonetheless, his story is an interesting one, for he was one of the first children to be treated this way in a British hospital: one of the first to receive state-of-the-art radiotherapy, in a dedicated cancer hospital, where the doses he received were calculated specifically for younger, and therefore smaller and still growing, patients.

Figure 1.1 Child receiving radiation at The Christie Hospital in the 1940s

Source: Tod (1940), reproduced by permission of The Christie.

Until the 1930s, childhood cancer was almost invisible. The majority of children who developed leukaemia or solid tumours were not diagnosed correctly, and treatment offered to those who were was limited: their early death was taken to be inevitable. Few doctors, even specialist surgeons, would come across more than one case of childhood cancer in their entire careers, so no expertise had been built up in general hospitals. In the 1930s, however, owing to observed increases in mortality rates and systematic attempts to assess and increase the utility of radium as a treatment, all kinds of cancer began to attract more attention. A number of the doctors interested in cancer began to tally the tumours they saw in children, and interested pathologists declared them different in kind from adult malignancies. As increased resources were poured into research on cancers commonly affecting adults, interest in paediatric malignancies, by virtue of their very peculiarity, became a special area of study for a small number of researchers and clinicians. Thus, childhood cancer began its slow transformation from a hidden disease of which a few doctors had little knowledge, to a research hotspot, generously funded by governments and charities, an especially fruitful topic for exploring the mechanisms of cell growth and division.

Some of the interested doctors were haematologists, members of a new specialism dealing with blood diseases, including leukaemia. All haematologists had laboratory facilities, for blood was an ideal – and easily accessible – tissue for investigations; and a few, especially in the USA, also had control of some hospital beds, allowing detailed study of the effects of blood diseases in patients, as well as in laboratory samples. In Chapter 2 we will examine work, following the Second World War, on leukaemia and other blood cancers as they became central to cancer studies, but in the 1930s few connections had been made between the study of blood diseases and research into solid tumours. As solid tumours accounted for the vast majority of cancer mortality in the population as a whole, leukaemia was not seen to be of particular research importance.

The Changing Place of Cancer in the Medical Imagination

Historically, cancer has not been an easy disease to treat, or to be seen to treat. Until the late nineteenth century, almost all patients suffering from the disease died whether they received medical attention or not. Thus, the majority of hospitals explicitly sought to prevent cancer patients from taking up valuable bed space, especially if the hospitals were charitably funded and wanted to appear effective. Institutions for cancer were rare, and, as Pinell (2002) has shown for France, were usually intended to serve as places where cancer patients could die. That such deaths were often painful and very distressing was seen as a valuable test of the devotion of attendant nuns.

In the early nineteenth century, only one of England’s charitably funded general hospitals catered for these otherwise shunned patients: the Middlesex Hospital had a cancer ward from 1792. Among the many specialist hospitals that developed in Victorian London, there was one for cancer, the London Cancer Hospital (now the Royal Marsden), from 1851. From the 1880s similar hospitals were opened in Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, and Glasgow; typically, these fused pity for the dying and a new interest in medical research and possible remedies (Murphy, 1986; Pinell, 2003). From the 1890s, the idea of organised scientific and medical research had taken root in the universities of Great Britain and the USA, following German precedents, with some investigations being funded in the expectation of useful results. Cancer became a popular subject, in part because it was understood to be a disease of cells – the product of excessive cell division – and thus a suitable route to a greater understanding of the basic building block of life.

At about the same time, scientifically minded surgeons were developing ambitious new operations to root out cancer. With anaesthetics available from the middle of the century, the introduction of antisepsis in the 1860s, and aseptic techniques during the 1880s, patients could tolerate more invasive procedures and dramatic surgical interventions became survivable. This extension of surgical procedures was closely linked with the new science of bacteriology, especially in Germany and those British and American hospitals that adopted a scientific approach to surgery. The radical new cancer operations were also influenced by new pathology theories, which understood cancers as local diseases that became generalised as cancer cells moved into other parts of the body: surgeons also attempted to remove the tumour’s surrounding tissue in order to capture any cells on the move.2 The discovery of X-rays in 1895 introduced a new modality of treatment that proved successful for some skin cancers. Soon afterwards came the discovery of radium, a miracle element exploited in small doses as a tonic, which, deployed in larger quantities, could burn away tumours. Around the turn of the century, these fresh intellectual and clinical avenues prompted the creation of many new organisations committed to understanding or combating cancer.

With surgery and medicine becoming more ambitious and funding for research increasing, cancer emerged from the shadows. This focus increased between the wars, along with cancer mortality rates, chiefly owing to ageing populations. The considerable dangers of X-rays and radium had also become clear at that time, as many of the earliest scientists and doctors to work with radiation had fallen sick from its effects. Most countries tried to control the distribution of radium, limiting large supplies to specialist cancer centres where appropriate expertise would ensure safety.3

As noted above, the Middlesex in London was the first British hospital to specialise in the care of cancer patients, and many of those instrumental in the founding of Great Britain’s first cancer research charity in 1902, the Imperial Cancer Research Fund, were active on its wards. Initially, the supported research was surgical, but it rapidly became clear that even apparently well-contained tumours could not be cured through surgery alone, and by the 1920s reports were arriving from radium centres in continental Europe suggesting that radiation, either alone or in combination with surgery, might be more successful. In the early 1920s, British research into the therapeutic possibilities of radiation, delivered as X-rays or as gamma rays from radium, was taken under government control, with the Middlesex a leading site for experimentation around therapeutic possibilities, especially for tumours where surgery was difficult or ineffective.

Though both expensive and dangerous as a medical treatment, radium appeared to hold great promise and, during the 1930s, several governments began to establish regional centres for radiotherapy. Owing to the pioneering work of Marie Curie and her husband Pierre, France was a leader in this development, with the Swedish centre in Stockholm also becoming an international model. In Great Britain, radium supplies had been collected for medical use in the First World War, and were therefore controlled by the government. The Medical Research Council, established just before the First World War, had realised that radium could link medicine and physical science, thereby stimulating the growth of more scientific methods in clinical research (Murphy, 1986; Pickstone, 2007).

The 1939 Cancer Act recommended the provision of radiotherapy be extended through a network of regional centres for cancer sufferers. Although the Second World War prevented nationwide implementation of the proposals, the Act can be viewed as the expansion of a process already well underway: by the end of the 1930s, the old specialist centres for radiotherapy treatment, in London, Manchester, and Glasgow, had been joined by new regional centres where radiotherapy was hailed as an innovative and properly ‘scientific’ treatment for cancer, one which might succeed in cases where surgery failed.

In the USA, several cancer hospitals and research centres had established international reputations by the end of the 1930s. The Memorial Hospital for Cancer and Allied Diseases in New York was especially noted for its studies of childhood cancer. The Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minnesota, was also considered to be a cutting-edge research centre, for its refinement of diagnostic radiology to detect and measure cancers, and for a separate department researching therapeutic radiotherapy. However, despite these research hotspots American radiotherapy did not become generalised as a separate specialism until long after the Second World War, owing, in part, to the dominance of surgeons in cancer care management and partly because of the medical profession’s opposition to any state control of radium.

In general, American conditions of practice encouraged specialisation, as doctors could both practice general medicine for a group of regular patients and undertake specialist work in hospital wards and clinics in a way not easy to manage in Great Britain, even before the National Health Service (NHS); radiotherapy was peculiar in this regard, emerging as a specialism later in the USA than in Europe. Paediatrics, as we shall see, was a favoured ‘semispecialism’ of those American doctors who saw themselves as catering to families; the majority of child-specific work in Great Britain was undertaken by general practitioners and school-delivered medical services. Specialists in paediatrics were few in number, restricted to children’s hospitals in the big cities, where they would manage the care of children suffering from rare conditions.

The Organisation of Paediatrics in Great Britain as a Medical Specialism

Paediatrics, the branch of medicine concerned with the care of children and infants, had become relatively well established in mainland Europe and the USA in the early twentieth century, but did not take shape as an organised specialism in Great Britain until the 1930s. Professional associations were founded to promote the interests of those seeking a career specialising in treating childhood illnesses, including the American Medical Association’s Pediatric Section in 1880 and the American Pediatric Society in 1888. In major cities across the USA and Europe, doctors successfully practised as paediatricians, yet in Great Britain very few medical practitioners established themselves as paediatricians until the 1930s (Historical Archives Advisory Committee, 2001). The first historian of the British Paediatric Association (BPA), Hector Charles Cameron, noted the reasons for this in his account of the Association’s first 24 years:

The delay in the appearance of the paediatric specialist was not due to lack of interest in the subject. It was a result of the peculiar organisation of the profession found in this country alone, divided as it is into two unequal parts, a larger of general practitioners, a smaller of consultants (1955, p. 1).

In continental Europe, state institutions that housed children had provided a basis for paediatric specialisation and education, but tax-funded institutions in Great Britain were rarely used as an avenue for studying children’s health or treating their diseases; until the establishment of the NHS in 1948, medical education was largely delivered in charity hospitals, which only admitted children in exceptional circumstances. As doctors’ work in charity hospitals was unpaid, it was very difficult to establish any specialism that did not also attract a significant volume of private practice; wealthy families with sick children were usually content to consult their regular family physician rather than seek out an unfamiliar specialist.

Partly owing to this exclusion of children from the majority of medical charities’ services, larger British cities had supported charity outpatient services that focused on the needs of children. The first of these was created in Holborn, London, in 1769, but lacking sufficient funding it closed its doors after 12 years. A second dispensary for children was launched in London in 1816, and while it languished after the death of its founder in 1824, it was subsequently reinvigorated by Charles West, who went on to create the Hospital for Sick Children in Great Ormond Street in 1852 (Lomax, 1996, pp. 5–6). Manchester’s medical provision for children similarly grew from an outpatient service. The General Dispensary for Sick Children started treating patients in 1829; it remained a small charity until the middle of the century, but inpatient treatment was established in 1859, and a decade later work had begun on a purpose-built building in the suburbs of the city, where children could be treated in cleaner air. This was the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Pendlebury (Barnes, 2010).

Social and medical interest in the health of mothers and children had been on the increase since the 1850s, with a growing number of maternity hospitals admitting sick babies. Public health campaigns against infectious diseases also provided support for children’s hospitals, as did the emigration to Great Britain of a few European-trained doctors with radical political ideas regarding who should have access to healthcare. The expansion of surgery in the 1880s, as noted above, also affected the flow of patients to children’s hospitals, increasing the numbers applying for admission and attracting a small number of middle-class families alongside the poor.

Until this time, then, children’s hospitals had existed because children were excluded from the general hospitals, not because of any specialised knowledge possessed by their medical staff. However, at the end of the nineteenth century, as a new focus on ‘child studies’ developed, this situation began to change. Doctors and scientists became increasingly interested in diseases of development: as these were so unlike adult diseases, paediatricians acquired a distinctive intellectual claim to expertise.

Interest in children was then greatly enhanced by the British government, which, like most others, began to promote the health of the population in order to secure the strength of the nation: for a nation to successfully compete in an age of industrial and colonial rivalry, it needed a large and healthy population. Welfare systems for maternity, infants, and schoolchildren became a national priority, in Great Britain and across Europe and the USA (Cooter, 1992). Initial interest focused primarily on infectious diseases, but following the First World War, researchers and clinicians in Great Britain, the USA, and Europe widened the focus to include children’s development, studying infant feeding and family diet, and researching the biochemistry behind health and disease in efforts to explain the widespread debilitating health conditions observed in young men called up for military service (Shulman, 2004). As both interest and services increased, British doctors concerned with child health began to establish professional organisations. This enabled them to call for greater investment in funded hospital posts in paediatrics, where the study of child health could be furthered alongside the provision of treatment for childhood illness.4

Dining clubs for children’s doctors were meeting regularly in London from 1918, in Scotland from 1922, and in the provinces from 1924 (Cameron, 1955, pp. 3–6). Canadian paediatrician, Donald Paterson, who had moved to Great Britain after the First World War and tirelessly advocated for a national professional body on the model of the American Pediatric Society, brought these informal societies together. The inaugural meeting of the BPA, with Paterson as honorary secretary, was held in 1928. That same year, Birmingham Children’s Hospital became the second hospital in the country to fund a Chair in child health, awarding the post to Sir Leonard Parsons, who had trained at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London (Stevens, 2001; Dunn, 2006...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Childhood Cancer: A Disease Apart

- 2 The Rise of Childhood Leukaemia

- 3 Working with Larger Numbers: The Development of Large-scale Clinical Trials

- 4 Cancer Microbes, the Tumour Safari, and Chemical Cures

- 5 Making the News and the Need for Hope

- 6 A New Breed of Doctor

- 7 Living with Uncertainty: Three Patients on Trial

- 8 Experiences of Survivorship

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index