- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

We are living in the age of imagination and communication. This book, about the new ways time is experienced and organised in post-industrial workplaces, argues that the key feature of working time within knowledge, and other workplaces, is unpredictability, creating a culture that seeks to insert acceptance of unpredictability as a new 'standard'.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Unpredictability: The Effects of a New Working Time Culture

Working time shapes much of our experience of life: the duration of the work day, the pace of work, the seasons of work, and the culture associated with working time. As society changes, new temporal cultures are created; new understandings occur, and new contracts both implicit and explicit, are agreed to and disputed. Work organisations are associated with different types of temporal culture: that is, different understandings of what is the normal and acceptable way to distribute and arrange the time of work. This book identifies and illustrates the experience of workers whose time culture is based on principles of unpredictability and uncertainty rather than routine and standardisation. In this book, I will argue that a key feature of working time within high-tech industries is unpredictability, which alters the way time is experienced and perceived. It affects all aspects of time, from working hours to work organisation, to career, to the distinction between work and life. Although many desire variety in work and the ability to control working hours, unpredictability causes dissatisfaction. This book investigates how a culture of unpredictability results in unexpected tensions.

What is said about working time?

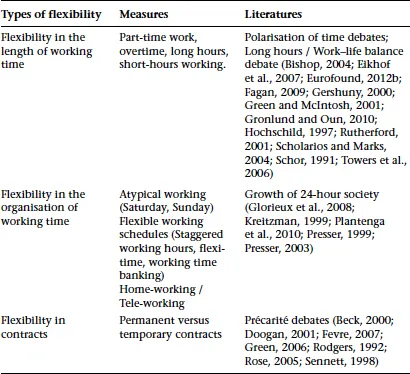

There is little agreement about how change to Western economies and the associated changes in work organisation will alter working time. Considerable variations in work time organization are evident between countries and sectors (Chung and Tijdens, 2012; Kerkhofs et al., 2008; Pronovst, 1986). A number of key debates refer to an increase in flexible working time, albeit the flexibility in question varies along three dimensions: flexibility in the length of working time, flexibility in the organisation of working time and flexibility in the length of working time contracts. Table 1.1 outlines the various working time measures associated with each type of flexibility and the literatures that tend to address them.

With the exception of the permanency discussions, these debates fail to appreciate that an important change to working time is the emergence of unpredictability as an additional component of working culture, particularly in those occupations characterized previously as having ‘standard’ working time arrangements and careers. The predictable is becoming unpredictable. Unpredictability is rarely measured. Established statistical surveys such as the European Working Conditions Survey tend to ask about ‘the usual’ rather than the unexpected. As a result, the working time debates have focused on more easily quantifiable variations in the length of the working week, the spread of working time to the evenings and the weekends, and the length of working time contracts.

Table 1.1 Various working time measures associated with each type of flexibility and the literatures that tend to address them

The persistence of standard time

The debates on the duration of working time identify changes in work organisation which cause working time to increase, particularly among professional and managerial workers (Hochschild, 1997; Rutherford, 2001; Schor, 1991). Much of the duration discussion has been crystallized into an examination of how longer hours impact work/life balance and family well-being (Eikhof et al., 2007; Scholarios and Marks, 2004; Towers et al., 2006) such that work–family conflict is now ‘the dominant ... construct in survey-based work–family research’ (Gronlund and Oun, 2010, p. 179).

As on a national level working hours are decreasing (Eurofound, 2012b; Gershuny, 2000; Green, 2001), a strand of the duration-themed literatures has focused on the extent to which various national working time structures can be said to have polarized. While long hours are evident for some workers, a countertendency, particularly in the UK, has seen the increase in part-time work, in part due to the increased participation of women and students in the paid workforce (Fagan, 2009). These discussions have fruitfully alerted us to the fact that national averages therefore can mask a division of the working population into those who work very long hours and those who work very short hours (Bishop, 2004; Fagan and Warren, 2001; Wickham, 2000).

When looking at variations in the duration of work hours among European states, national differences are evident in the various degrees of polarisation found. At one extreme, the standard working hour day is still prevalent (such as in the new EU member states); at the other, no standard exists (as in the UK). Within these two extremes, European states vary. Often there is a standard peak which encompasses most workers; the standard varies from country to country. Thus, for example, in France most people work between 31 and 35 hours a week, whereas in Denmark most work 37 hours a week. However, in some countries, there is an additional short-hours peak which reflects high rates of part-time working (such as the Netherlands, with high numbers at 20 hours a week) and in some countries a long-hours peak (for example, in France there is a secondary, smaller peak at 38–39 hours) (Plantenga et al., 2010).

Duration research has identified an important truth: within most countries, it is possible to identify a working hours duration which can be considered ‘standard’ (the UK being a notable exception). Standard working time still exists. It is, however, under pressure. This book will argue that this pressure isn’t just a pressure to increase working hours, but also to alter hours in an irregular and unpredictable fashion. (This will be returned to in the next section.)

A second set of literature focuses on changes in how working time is arranged. Driven by the globalisation debates and government policy objectives, these debates centre on the question of whether we are moving towards a ‘24-hour society’. Here the focus is on the dichotomy between typical work (that is, work conducted in broad terms between 9 am and 5 pm, Monday to Friday) and ‘atypical work’ (such as evening and weekend working), documenting and questioning the extent to which ‘atypical’ working structures are increasing. However, ultimately, while there is initial evidence that atypical work is increasing in the United States (Kreitzman, 1999; Presser, 1999; Presser, 2003), there is little evidence that atypical work has increased in Europe to the extent that we are working in a ‘24-hour society’ (Eurofound, 2012a; Glorieux et al., 2008; Plantenga et al., 2010). Once again, the standard is surprisingly persistent.

A third group of working time literature looks at working time from the perspective of career and working lives and is centred around questioning the extent to which impermanent work is replacing permanent contracts (Beck, 2000; Doogan, 2001; Doogan, 2005; Sennett, 1998). For the pessimists, the debates crystallise around often-rhetorical claims of increased precarity (Beck, 2000). In rebuttal, it is argued that, certainly until the recent crisis, there is little empirical evidence within Europe to match the assertion of increased impermanency at work (Doogan, 2001; Doogan, 2005). Once more, the standard is persistent.

Commentators have moved the discussion towards an assessment of whether workers feel impermanent (although they are no more so than previous generations) and why such fears may be evident. The career literature highlights the ways that perceptions can vary from reality; there is a disconnect between perceptions of change, government policy, and the lived reality of most workers. As such, the career literature is of additional importance to this book as it addresses the extent and perceptions of unpredictability. These debates outline how a culture of impermanency frames employees’ perceptions of the norm and thus the options and strategies that are available.

The emergence of unpredictability

There are many valuable insights to be gained by examining working hours along these dimensions, the chief of which is the remarkable persistence of standard working time, particularly in terms of how long the working day is, on what days we work and our careers. The European Foundation for Living and Working conditions emphasizes the persistence of working time standards: ‘European working hours have – overall – remained remarkably standard. For most indicators of working time stability, the figures have remained the same since 2000, with 67% of workers working the same numbers of hours per week, and 58% working the same number of hours every day’(Eurofound, 2010). However, for all the evidence that standard working time persists, there is also evidence of an emerging unpredictability.

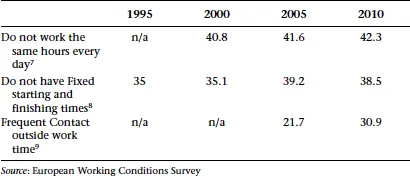

Although there are few survey instruments that directly measure unpredictability, there are a number of variables within the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) that can serve as a proxy for unpredictability. These are variables that measure variability in working time arrangements, work outside ‘normal’ working hours, and control over one’s working hours. In 2010, 42.3 per cent of workers did not work the same hours every day,1 32.8 per cent did not work the same hours every week,2 and 38.5 per cent did not have fixed starting and finishing times.3 Work includes on-call time4 for 20.2 per cent of Europeans. A similar percentage, 22.9 per cent, do not work the same number of days each week. 31 per cent of people work at least once a month in their free time in order to meet their work demands.5 A significant proportion of the European working population are not working regular hours. This proportion has been increasing – though this increase has been relatively small (see Table 1.2) In the last five years,6 there has been an increase of around 2 per cent in those who do not work the same hours every day and those who do not have fixed starting and finishing times.

The European Working Conditions Survey has other measures of variation. In 2010, they asked how often employees worked in their free time to meet work demands; for 15.5 per cent this happened once a week a week of more, for 15.6 per cent this happened once or twice a month. Almost a third of employees surveyed spend some of their free time each month ‘at work’10. Control over one’s working hours suggests a certain variation and unpredictability in working hours. Reidmann reports from the Establishment Survey on Working Time and Work–Life Balance (ESWT) that on average 48 per cent of those surveyed reported the existence of some form of flexible working time arrangement, allowing for the adaptation of working hours according to personal wishes of at least part of the workforce’ (Riedmann et al., 2006). A survey of Australian working time reported that 19 per cent of respondents had unpredictable daily working hours and 25 per cent had unpredictable weekly working hours (Denniss and Baker, 2012).

Shifting the focus

Unpredictability, therefore, is clearly experienced by a significant proportion of the European (and Australian) workforce, and along some measures is increasing. The duration and working time arrangement debates in the main sideline the issue of unpredictability. What happens if, instead, we include unpredictability in our analytical frameworks? Table 1.3 outlines how the various working time measures can be grouped if working time is seen not only in terms of the standardisation vs. destandardisation axis.

Table 1.2 Significant proportion of the European working population are not working regular hours

Following the European Foundation’s definition,

Employment refers to the contractual relationship between the employer and the employee (when the worker is not self-employed). ... The contract of employment makes the employee subject to the employer’s command or control as to the time, place and manner in which the job is to be performed. The contract also sets out the amount and frequency of pay, and the length of the employee’s working week or day, together with information on paid leave and conditions of notice fixed. (Eurofound, 2012a, p. 11)

In the context of this book, standard employment refers to a working hour duration or arrangement which in the main conforms to a national norm, usually between 33 and 46 hours (depending on the county as we have seen above), worked Monday to Friday, between the hours of 9 and 5 (again with national variations as to the what arrangement of hours are standard).

Where working time demands are predictable and regular, working time arrangements are delimited by formal working time contracts. In some sectors, such as industrial manufacturing, this gives rise to the working time standard that underpinned many of the original debates on working time, which were centred on the growth of industrial working time. These debates centred on the experience of the assembly line worker, Fordist factory production and Taylorist organisational techniques. E. P. Thompson’s influential Time & Work Discipline argued strongly that these production processes operating within a capitalist framework, shaped the temporal culture of industrial society (Thompson, 1976). In the modern era, Taylorism persists in companies such as Foxconn, one of the world’s largest employers, with a workforce of 1.4 million. The assembly lines in China run on 24-hour non-stop schedules. For workers, this is accompanied by extremely long working hours that contravene legal restrictions (12-hour days are the norm). Overtime is often compulsory, there is pressure to increase work rates, toilet breaks are restricted and holidays are few (one day off every two weeks). In addition, the labour process is mundane and repetitive (Chan, 2013). In some sectors, such as retail work, the working time arrangements in place (such as shift work or part-time work) lend themselves to non-standard arrangements, in the sense that these workers work at atypical times (such as the weekend or the evenings) and for atypical durations (very short hours). As these sectors have grown, the working time literatures have shifted to focus on the examination of the working time experiences of these workers, and have concerned themselves with the growth of a 24-hour society and the spread of industrial rationality to the service sector (Ritzer, 1995; Taylor and Bain, 1999). Most of the current debates on working time fall into these two main frameworks. This is unsurprising as industrial working time was indeed the most powerful driver of working time standards, and the growth in the service sector has caused the most changes to that model. However, by limiting the debate to these dimensions, we are limiting our understanding of additional pressures.

If we now move to consider those whose working time demands are irregular and unpredictable, two further groups emerge. In the industrial era, it was the dockers, the last outlier against industrial working time who had both non-standard contracts and unpredictable working time (O’Carroll, 2006). There have been attempts to introduce such extreme flexibility among service sector workers through the use of zero-hour contract type arrangements (Evans et al., 2001; Rubery et al., 2005), but whereas they are allowable in some countries such as the Netherlands (Eurofound, 2008), in others, such as Ireland, working hours legalisation has limited their operation. Few workers fit exclusively within this category, more often combining some aspects of these working time arrangements, such as on-call work and telework, with the more regular working time arrangements mentioned above.

The final category in Table 1.3 refers to those who have unpredictable working time demands and standard working time arrangements. It is this category of working time arrangements that this book focuses on. This category of worker is distinguished from all the others in that often their working time arrangements include a measure of unpredictability. These are workers who have both a standard working time contract, in the sense that they work close to their national standard (for example, 9–5, Monday to Friday), and agreements (sometimes expressed in contracts by requirements to work flexibly) which cause occasional deviation from that standard.

It becomes clear, therefore, if unpredictability is included as a dimension in the debates, that the focus on the divergence between typical and atypical working arrangements, or between long hours and short hours, has obscured another change to the temporal culture of working life: the increasing insertion and acceptance of unpredictability as a new ‘standard’ for those working time structures that were previously considered to be ‘regular’.

Unexpected dissatisfaction

When we shift our focus to issues of predictability and unpredictability, it becomes evident that unpredictability causes problems. Two paradoxes are evident in the European Working Time Surveys. Firstly, variable time-schedules have been linked to increased dissatisfaction with work–life balance (Parent-Thirion et al., 2007). Secondly, autonomy over working hours has been linked to increased dissatisfaction with working hours (Parent-Thirion et al., 2007, p. 79). Despite reports of employees’ desires for more variability and control over their hours (Lyness et al., 2012), unpredictability in working time creates tensions for employees. This book is about those tensions.

Parent-Thirion and his colleagues arg...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Unpredictability: The Effects of a New Working Time Culture

- 2 The Long Hours Myth: Working Hours in the Software Sector

- 3 The Unpredictable Clock: The Time of Knowledge Work

- 4 Spaghetti Time: Organisational Culture, Multi-tasking and Boundaries

- 5 Constrained Autonomy and Disrupted Bargains

- 6 Nomads: Unpredictable Career Paths

- 7 Time, Work-Discipline and Unpredictability

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Working Time, Knowledge Work and Post-Industrial Society by A. O'Carroll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Personalmanagement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.