- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Arab Food Sovereignty

About this book

A political economy analysis of the history of food security in the Arab world, including the role played by the global food price crisis in the Arab Spring and the Arab response aiming at greater food sovereignty via domestic food production and land acquisition overseas – the so-called land grab.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Political Economy of Arab Food Sovereignty by J. Harrigan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Background

Three recent phenomena serve as the background to this book: the global food price crises of 2007–08 and 2010–11, the Arab Spring, and the growing practice of foreign land acquisition, sometimes referred to as ‘land grab’,1 whereby richer food-scarce countries acquire land in poorer, land-abundant countries to directly source their food needs. This book argues that these three phenomena are intimately linked and are part of the new political economy of food in the Arab region, one whereby Arab states are developing a new approach to food security which we have called macro food sovereignty. As pointed out by Zurayk (2012, p. 19), food politics and its relationship to power is of crucial importance to the Arab region yet remains under-studied. This book hopes to help fill that gap by providing a political economy analysis of food security and food sovereignty in the Arab world.

The global food crisis

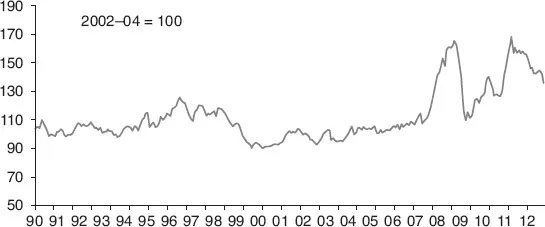

The years 2007–08 witnessed a serious global food price shock. This was to become part of the Triple F crisis – food, fuel, and financial crises. In 2007 and the first half of 2008 global food prices escalated. Between 2007 and 2008 the FAO Food Price Index increased by nearly 50 per cent (Figure 1.1), and from March 2007 to March 2008 wheat prices around the globe rose on average 130 per cent, whilst relative to the US Consumer Price Index, rice prices nearly tripled2 (Dorward 2011, p. 647). Food, energy, and commodity prices fell in the latter part of 2008 due to a weakening global economy and the onset of the global financial crisis. However, a second global food price crisis hit in 2010–11. Food prices again started rising in June 2010, and by February 2011 the FAO Food Price Index had hit record levels (refer again to Figure 1.1). Within 12 months the international prices of maize and wheat had roughly doubled.

Although overall grain production and stock levels, particularly in developing countries, were higher in 2010–11 than they were during the 2007–08 crisis, most of the underlying structural factors underpinning the earlier crisis persisted. In addition to rising food prices, food price volatility in the form of sharp peaks and troughs has also emerged as a problem since 2007 (see Figure 1.1). We shall refer in this book to these price events that took place between 2007 and 2011 as the global food crisis/shock.

A combination of demand-side and supply-side factors contributed to the food crisis. Demand factors included growth in food demand and changing diets in countries like China and India, biofuel demand for crops, and panic buying and speculative activities in food markets. Supply-side factors included thinness of global food markets (meaning only a small percentage of production is actually traded there), declining growth rates of food crop productivity, low stock levels, climatic shocks, the effects of climate change, and export bans by major exporters.

The causes of the crisis are analysed in more depth at the start of Chapter 4. Many analysts agree that these higher food prices are here to stay (Oxfam 2011a; OECD and FAO 2008; World Bank 2008a, 2009a; IFPRI 2011a). OECD and FAO (2009) predicted that global food production will need to increase by 40 per cent by 2030 and by 70 per cent by 2050 to meet projected demand, and that for the next 10 years at least food prices will remain considerably above their former long-term averages.

Figure 1.1 FAO food price index

Note: The FAO Food Price Index is a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food commodities. It consists of the average of five commodity group price indices (representing 55 quotations), weighted with the average export shares of each of the groups for 2002–04.

Source: http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/

It is important to note that Dorward (2011) and others, such as Headey and Fan (2010), have pointed out that the global food price crisis needs to be placed in historical context. The price movements discussed largely refer to nominal prices. But when we look at real food prices, relative to the US Consumer Price Index (CPI), the spike in grain prices in 2007–08 was considerably lower in ‘real terms’ than prices in 1974 and, according to Dorward, ‘not much higher than prices at various times in the late 1980s to mid-1990s’ (Dorward 2011, p. 648). There seems therefore to be a paradox: heightened concern for food security at a time when real food prices are historically low (despite the massive spikes in nominal prices).

Dorward explains this paradox by pointing out that the use of advanced economy price indices, such as the US CPI as the deflator to calculate real food prices, is misleading in that it ignores (1) the high share of food in poor people’s expenditures and (2) the indirect effects of income growth on expenditure patterns of rich consumers. As a result, it does not capture the true effects of rising food prices on poor people. That is, ‘poor consumers have not experienced the same falls in real food prices and are more vulnerable to price shocks’ (ibid., p. 647). Dorward therefore suggests that different price indices should be developed to take full account of differences between consumer groups, and in particular – if we are to capture the effect of rising food prices on welfare and poverty – changes in food prices should be measured relative to income, not relative to non-food prices.

In addition to concerns about the global food price crisis in terms of its impact on the poor, Dorward states that the crisis raises concerns about the volatility of global food prices and about the potential threats to food supplies, since export bans and declining global stocks were some of the factors behind the crisis.

Regardless of the debate on how best to measure real food prices, the nominal price increases of 2007–08 and 2010–11 came on the back of several decades of gradually falling or stagnant nominal food prices,3 and they focused global attention on the issue of food security. Much was written about the imbalance in global food markets and its implications for food security (OECD and FAO 2010; Deininger and Byerlee 2011; Evans 2009; Godfray et al. 2010). The international community also rallied around the issue with Global Food Summits in June 2008 and November 2009. In 2010 the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) launched its Feed the Future Initiative, the World Bank Group maintained its recent increased annual commitment to agriculture and related sectors at around US$6 billion, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) launched a large new research programme, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation revitalised its agricultural strategy. In June 2011 the G20 agricultural ministers met and agreed to tackle food price volatility and food insecurity, and at the 2011 Davos Forum the world’s business and society leaders initiated their New Vision for Agriculture. In the same year OXFAM launched its GROW campaign to push for policy and practice changes from the global to local levels to grow more food fairly and sustainably (IFPRI 2011a).

The new concern for food security issues was particularly marked in the Arab world due to the region’s heavy reliance on food imports. According to IFPRI (2011b, p. 23): ‘The effects of high and volatile food prices are particularly harmful for countries with high net food imports. Because these countries purchase a large share of their food requirements on global food markets, price increases and price volatility transmits faster and more directly to the national level’. Concern for food security in the Arab world resulted in numerous high-profile publications by international bodies (FAO 2008a; World Bank 2009a; ESCWA 2010; Breisinger et al. 2010, 2011a, 2012) as well as a high-level international IFPRI/UN-ESCWA conference, Food Secure Arab World: A Road Map for Policy and Research, held in Beirut in February 2012.

Swinnen (2011) has pointed out how the global food price crisis has led to a dramatic shift in views concerning the price of food. Prior to the crisis, the widely held view, especially in NGOs and international organisations, was that low food prices – partly caused by the agricultural policies of rich countries, such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) – were bad for developing countries and the poor. He documents how the 2007–08 and 2010–11 global food crises led to a dramatic reversal in this view such that high food prices are now seen to be having a devastating effect on developing countries and the poor.

He offers several explanations for this seemingly inconsistent volte face. Firstly, the change in view may reflect a focus on different groups negatively affected in each period. For example, farmers in developing countries were harmed by the low food prices prior to 2007 whilst net food consumers were harmed by the high food prices post 2007, with analysis focusing on the negatives in each period rather than any of the positive effects. Secondly, the potential positive effects of each price regime may not have passed through; that is, consumers in developing countries may not have experienced the low prices before 2007, and farmers may not have benefited from the high global food prices after 2007.

Thirdly, the new emphasis on the negative effects of high global food prices may reflect an urban bias and pressure from urban interests, since urban consumers in developing countries were a politically vocal group who were adversely affected by the global price shock. Fourthly, NGOs and international organisations, with their concern for legitimacy and fundraising, aided by the mass media, have latched onto the negative development effects of the global food price hike and, ignoring any of the potentially positive effects, have dramatically changed their view on the ‘right price of food’ as part of their marketing and self-promotion strategy.

IFPRI (2011b, p. 21) provides one good example of an international organisation that has focused on the negative effects of the global hike in food prices since 2007 by outlining the potential adverse welfare effects of both high and volatile food prices. High prices harm consumers by reducing their ability to buy food and leaving less income for other essential commodities and services such as health care and education. For producers, high food prices will increase their incomes only if (1) they are net sellers of food (many poor producers also need to buy food) and (2) if the higher global prices are transmitted down to producers and their input prices do not also rise. IFPRI argues that many of these conditions needed for producers to benefit from higher global food prices have not been seen since 2007. In terms of food price volatility, IFPRI suggests that it could harm producers due to large rapid changes in prices that may discourage input use and investments, which in turn would reduce agricultural productivity and supply, leading to higher prices.

Price volatility also draws investors and speculators into food markets, further exacerbating price swings. In response to both rising and volatile prices, families, especially poor families, are often forced to reduce their calorie and nutritional intake, which can lead to long-term irreversible nutritional damage, especially among children, and thus worsen the problems of hunger and poverty. The severity of the impact of rising food prices depends partly on the coping mechanisms adopted by families and partly on their ability to access social safety nets and other social protection schemes.

The Arab Spring and the new politics of food

As the most food import dependent region in the world, Arab countries were badly hit by the global food price increases. Although Arab governments tried to mitigate the rising costs of imported food, they were unable to prevent the importation of food price inflation. To varying extents food prices increased, and government expenditures on maintaining food subsidies and cushioning the impact also went up. This led to economic and social hardship in many countries in the region, especially the resource-poor Arab countries – trade and fiscal deficits increased, inflation increased, and poverty and nutritional problems emerged as both poor and middle-class families found it increasingly difficult to afford food.

We argue in this book that food price increases were an important trigger for the Arab Spring. Arab Spring is a media term for the revolutionary wave of demonstrations and protests (both nonviolent and violent), riots, and civil wars in the Arab world that began on 18 December 2010. To date, rulers have been forced from power in Tunisia, Egypt (twice), Libya, and Yemen; civil uprisings have erupted in Bahrain and Syria; major protests have broken out in Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, and Sudan; and minor protests have occurred in Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and Western Sahara.The sectarian clashes in Lebanon were described as spillover violence from the Syrian uprising – hence the regional Arab Spring.

The protests have shared some techniques of civil resistance in sustained campaigns involving strikes, demonstrations, marches, and rallies, as well as the effective use of social media to organise, communicate, and raise awareness in the face of state attempts at repression and Internet censorship. Many Arab Spring demonstrations have met with violent responses from authorities, as well as from pro-government militias and counter-demonstrators. These attacks have been answered with violence from protestors in some cases. A major slogan of the demonstrators in the Arab world has been Ash-sha`b yurid isqat an-nizam (‘the people want to bring down the regime’).

Although the Arab Spring was first and foremost a political movement to remove oppressive undemocratic regimes, it also had important socio-economic underpinnings in the form of food price inflation as well as growing levels of unemployment and increasing inequalities. We review the economic, social, and political impact of the global food crisis on the Arab world in Chapters 4 and 5 of this book.

The conjunction of the global food crisis and the Arab Spring provides an oportunity to reappraise food security in the Arab region – and such reappraisal is the purpose of this book. We argue that food security cannot be assessed from a purely economic perspective, as is the tendency of international organisations such as the World Bank, but that a political economy perspective is essential. The role of food prices in the Arab Spring illustrates that issues of food security are intimately bound up with domestic politics.

In addition to the close link between food security and domestic politics in the Arab world, geopolitics is an important dimension of food security in the region. We show in Chapter 3 how food has been used in the past as a geopolitical weapon in the region by the United States of America (US). ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Food Security Status of Arab Countries

- 3 The Evolution of Food Security Strategies in the Arab World

- 4 Causes of the Global Food Crisis and its Impact on the Arab World

- 5 The Arab Response to the Global Food Crisis

- 6 Land Acqusition Overseas – Land Grab or Win-Win?

- 7 Policies for Arab Integration into Global Food Markets and Arab Domestic Agriculture

- 8 Reforming Social Safety Nets

- 9 Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index