eBook - ePub

Environmentalism, Resistance and Solidarity

The Politics of Friends of the Earth International

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmentalism, Resistance and Solidarity

The Politics of Friends of the Earth International

About this book

Drawing from a rich mix of survey data, interviews, and access to internal meetings, Brian Doherty and Timothy Doyle show how FoEI has developed a distinctive environmentalism, which allows for the differences in context between regions and across the North-South divide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environmentalism, Resistance and Solidarity by B. Doherty,T. Doyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Environment & Energy Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

1

Transnational Social Movement Organizations

The speed of international financial exchanges and the mobility of transnational corporations is a central feature of the current era, but it is far more than just capital which is crossing borders, and blurring, confusing and reconfiguring boundaries (Castells 1997). Ideas systems such as environmentalism, championed by social movements, complete with globally recognized symbols, are also moving across the globe. There may be some intrinsic characteristics of environmental movement organizations (EMOs), which allow them to range so freely across borders. They are unusually adept at playing transnational politics, and, as such, are a fruitful vehicle through which to view the mechanics and organics of transnational political spheres. Their unique characteristics may allow them access to transnational realms, which are more prohibitive to others. These qualities range from the essential properties of ecological issues, the ability of the ‘environment’ symbol to be constructed so diversely, to the forms of political fluidity, which the social movement form allows and encourages.

It could be argued that environmental ills determine, to an extent, that transboundary crossings must be made: there may be an ecologically determined imperative that has increasingly pushed environmentalists across the globe to work more closely together. In this manner, environmental issues are sometimes construed as ‘beyond politics’, as simply ‘a reality’ that has to be dealt with due to the fact that ‘we all share the same planet’. In turn, shared ecological problems and issues are seen in this light as an opportunity to bypass geopolitical borders, a chance to build new liberal alliances and end centuries of division and opposition: an imposed construction of the universal we – ‘We are all just the earth’s citizens after all.’

Yet, even if non-human nature possesses some essential properties, it must be understood that the ‘environment’ and its ‘management’ by humans are also social and therefore contested concepts. In short, regardless of how real the physical ‘environment’ actually is, one must also consider the social movement, which shapes and delivers an understanding of environment and its politics. Concepts of environment, then, are far from apolitical; rather, they are intensely politicized categories, championed by diverse (and sometimes oppositional) movements and utilized to create forms of collective identity, organization, behaviour, political activity, security and, most importantly, resource distribution.

To prove this point, we do not have to look any further than the ideational, organizational and operational realities of the three main transnational EMOs: Greenpeace International (GPI); the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and Friends of the Earth International (FoEI). Although all three are transnational environmental organizations, it is their differences that most accurately define them, as these strike at the very heart of what environmentalism is (how it is framed by each of them), and what environmental activism entails (their political repertoires). Indeed, a brief comparative analysis of these three green organizations is a useful exercise to begin this book, as it does two things: firstly, it describes the broad-brush reality of transnational environmental organizations – originally based in the North, now operating across the globe – by outlining key characteristics of their structure, their goals, their politics and their identities. Secondly, a comparison introduces – and makes distinct – certain significant features of Friends of the Earth (FoE) that define its polity, and these traits, in turn, constitute major themes informing subsequent theoretical and empirical investigations in this book.

After this comparative and theme-based discussion, we will turn our attention to methodological issues, mapping out both our epistemological and technical fixings on the subject matter. As FoEI is a relatively new transnational form of movement, our methodologies, both in conceptual and in practical terms, were often challenged in this project’s research, writing and completion. In the final pages of this chapter, we provide a finding guide for the rest of the book, detailing our order of argument and its exposition.

Global green non-governmental organizations

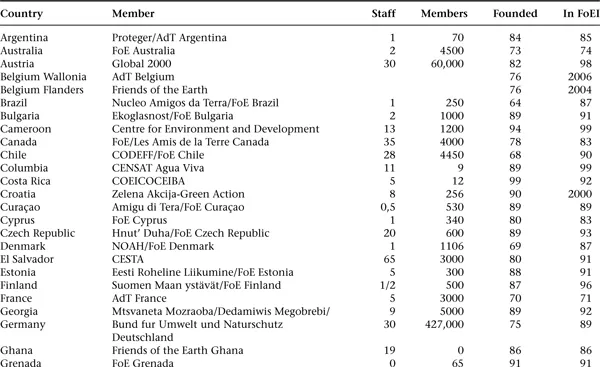

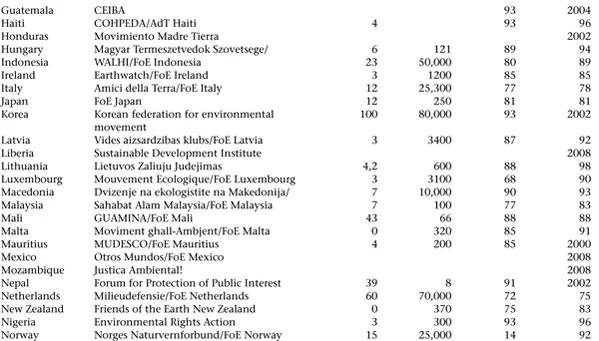

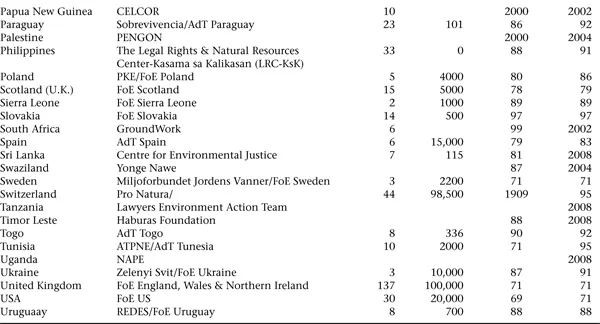

FoEI was formed in 1971 from an alliance between the national FoE groups of the United States, France, the United Kingdom and Sweden. In the four decades since then, transnational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have grown apace, FoEI among them. With 74 national groups, organized into four regional blocs – Africa, Asia Pacific, Europe and Latin America and the Caribbean (ATALC) – FoEI is the largest of the environmental NGOs. Its national groups employ over 2000 staff and globally there are over 5000 FoE local organizations (see Table 1.1).

Although it is a transnational organization, FoEI1 was very much born within the politics of nation states. Indeed, its best-known slogan is ‘Think Globally, Act Locally’. One of the main differences between FoEI and the two other major international environmental NGOs – GPI and the Worldwide Fund for Nature – is that FoEI’s structure is decentralized and its national organizations have considerable autonomy, whereas the other two are much more centralized. It was only later in the 1970s that FoEI stretched its wings into other countries in the North and, more recently, in the 1990s and 2000s that it has expanded considerably into the global South. This transition of originally national-based environmental organizations into the transnational sphere is, in large part, a reaction to corporate-led globalization; but this is not a simple case of a structural cause producing an automatic effect on group behaviour. Before they could develop as an international federation the national groups and leading strategists within FoEI had to first resolve their different understandings of global politics and decide collectively the best strategy for FoE to pursue, nationally and internationally. Understanding how they have done this is the central focus of this book.

Table 1.1 National memberships and staff, Friends of the Earth International

FoE national organizations.

Sources: FoEI database (2002) and annual reports of national groups.

FoEI is a particularly interesting case because in the diversity of its 74 national groups, regional and local organizations, and over its 40 years of development, it evidences many of the variations and transformations in modern environmentalism, especially the growth of activism in the global South and the challenges this poses for the previously dominant environmentalism of the global North. In this book, we examine this question through a focus on FoEI’s internal life: how its member groups negotiate their differences; work together to decide on transnational campaigns and the particular environmentalisms that FoEI produces as a result.

The fact that WWF, FoE and Greenpeace have taken different paths is essentially a matter of strategic choice. But strategic choices are not made in a vacuum. They are influenced and constrained by structure, the configuration of institutions and societal and transnational cultures over which actors have no control as well as by the traditions of these organizations themselves, which may to any single generation of activists appear almost equally immutable (Rootes 2005: 24; Armstrong and Bernstein 2008).

To refer to FoEI as the largest global environmental organization – as we did above – is only a half-truth, depending on which criterion is selected to judge the size of an organization. All three of the major green organizations can be referred to as large, but in different ways. FoEI is large in range in that it has member groups in more countries. In comparison with FoEI constituted by 74 national groups, WWF has branches in 48, and GPI operates franchises in 40. Apart from differences in numbers, differences in nomenclature also indicate distinct organizational forms. In the case of FoE, its national organizations already existed independently as environmental organizations before they joined the FoEI federation. In fact, FoEI does not create national branches; rather, it relies on an approach for membership to it from a pre-existing group in the country in question. This pre-existence of organizational form and practice means there is considerable variety in organizational structures and traditions among its national affiliates and necessitates that the FoEI Secretariat works as a coordinating structure rather than controlling national groups. WWF has branches, with each branch operating very much at the behest of the central organization. Both FoE and WWF national organizations usually have grass-roots memberships (although not always; this question is examined in more detail in Chapter 9).

Greenpeace’s situation is at the opposite end of the spectrum. In fact, it does not have regionally representative groupings, but simply offices of professionals, who coordinate volunteers who, in turn, solicit subscriptions rather than membership from the general populace. Thus members of national organizations are in tens rather than thousands, despite the hundreds of thousands of paying supporters in many Northern countries. It is important to Greenpeace that it speaks with one global voice, which requires tight central control of national campaigns by the International Office. Joint campaigns with other environmental groups have usually been kept to the minimum so that Greenpeace can claim the credit for its campaigns. Therefore, Greenpeace operates as a hierarchy with power centralized in the international office in Amsterdam.

There has, however, been some relaxation of the Greenpeace model in recent years. Voting power was previously based on the income of national groups, meaning that those in Northern Europe and the United States controlled the organization, but this has been partly replaced by the principle of ‘one office, one vote’, although approval of the GPI budget is still dependent upon votes based on income (Berny 2009: 383). More Greenpeace supporters are trained to take part in direct action than was the case before, although their numbers are still very small compared to the subscribers in Northern countries and their actions are still centrally planned. Local groups, which previously existed mainly to fundraise, have more opportunities to engage in campaigns, although, again, these have to be pre-approved by the national office (Saunders 2007b; Berny 2009). And Greenpeace joins coalitions with other environmental organizations more than in the past, although not in the case of direct action protests. Notwithstanding these changes, Greenpeace remains a much more centralized organization internationally than FoE.

In fact, what membership entails is often fundamentally different in each of these three organizations. Writing about them in the United Kingdom, Rootes says:

One of FoE’s objectives is to encourage ‘people participating actively as citizens and organising, mobilizing and inspiring people to become active citizens’ (FoE 2003). Accordingly, FoE Regional Campaigns Co-ordinators work to involve local FoE groups and other local community campaigning groups and offer them support and advice … Greenpeace remains very much an elite-directed campaign organization, and its willingness to be involved in local campaigns is limited and conditional … WWF too is formally a membership organization … although in practice their national leaderships are able to set campaign priorities according to their own assessment of scientific advice.

(Rootes 2005: 17)

FoE’s commitment to national self-determination, coupled with its focus on promoting and building wider networks of active, though often fewer, members across the globe than WWF and GPI, has meant that it has more readily survived significant downturns in membership which have struck other large environmental organizations from time to time.

A social movement?

FoEI’s loose and decentralist confederation of national groups, its willingness to engage with other organizations within campaign-oriented networks and its more radical social goals are features often associated with a social movement model of activity, rather than that of a formal, constitutionalized organization. Thus, some scholars and activists see FoE not as an organization at all but as a movement. We argue, first and foremost, that FoE is an organization. This does not preclude it from working within the broader realm of social movements, but we do not see FoE as a social movement in its own right. Rather, we see it as a federation of national EMOs and a social movement organization (SMO), with FoEI specifically a transnational social movement organization (TSMO) – meaning that as an organization FoEI is imbricated as part of a wider transnational social movement (TSM) (Cohen and Rai 2000: 12).

Other scholars have been excited and perplexed by FoEI’s operational forms. In her comparative study – writing on the ‘agility’ and ‘adaptive capacity’ of both FoEI and GPI – Vanessa Timmer provides a thorough analysis of their different operational and organizational styles. She argues that while both FoEI and GPI have developed adaptability, based on their organizational viability, they are also different at the most fundamental level. She writes:

FoEI, as a ‘global grassroots movement’, continuously expands its tactical repertoire; develops collaborative partnerships; depends on a mass voluntary base; and resolves conflict through participatory dialogue; which I label the Agility Model of building adaptive capacity. In contrast, Greenpeace, as a ‘global campaigning organization’, specializes in high profile, nonviolent, direct action tactics; predominately operates independently; secures financial support; and resolves conflict through managing for coherence; which I label the Resilience Model.

(2007: 231)

So, if we use Timmer’s model, GPI (and WWF) can be understood to be global organizations, whereas FoEI actually constitutes a movement in its own right. Does this mean that the first two are NGOs while FoEI is a social movement?

Indeed, this is not just a question that interests political scientists and sociologists. At a meeting of its Executive Committee (Ex-Com) in March 2009 in Amsterdam, FoEI tackled this very question; it decided it was not a social movement in its own right:

While FoEI would like to become a social movement; we are not one now. Our political agenda is not clear enough. We cannot be a federation and a movement at the same time. As a federation, it is about the sum of the parts – member groups are at the center. In a movement, the political agenda is broader; it is not just about member groups. This is easier in a class struggle because class identity is clearer; it is more difficult to figure out how to build a political agenda about our vision of the world.2

It is interesting to note that FoEI aspires to be a social movement one day. These emic arguments – emerging from the organization itself – are critical to understanding the self-identification processes of the organization.

So, already, a brief descriptive discussion of organizational structure has led us to key questions as to what constitutes a social movement. This concept is an analytical construct, not a description of a given empirical phenomenon; there is no clear consensus among scholars on how to use the term social movement and so, at best, the criteria that various definitions set out provide a heuristic device, a Weberian ideal type, that can be used to understand and interpret empirical cases (della Porta and Diani 1998; Tilly and Tarrow 2007).

And, as becomes clear in the following chapters, there are important differences about what is understood to constitute social movements in different regions of the world. Even at this definitional level, there are significant contextual differences affected by both time and place. For example, in the aforementioned Ex-Com meeting, the FoEI activists themselves conceptualized distinctions between ‘traditional social movements’ and ‘new social movements’:

Depending on history and context, we must acknowledge the differences in social movements. A social movement needs a shared paradigm, a political agenda and to be allied with many sectors. Traditional social movements were about class struggle. ‘New social movements’ are not as much about class but around a common political agenda.

Drawing from the definitional debates on social movements, we identify four central elements (della Porta 2007: 7–8). The first feature of social movements is that they must have some common identity which is not simply based on ideas, but also expressed in the ‘taken for granted’ practices and culture developed over time by participants in collective action, broadly its ‘habitus’ (Bourdieu 1990: 56) or its tradition. Social movements in this sense are not momentary coalitions but develop their collective identity over time as they face the question of defining ‘who are we?’, ‘what do we believe?’ and ‘how should we act?’

A second feature is that to assess empirically who is in the movement, we can measure the interaction between participants and between groups as opposed to simply counting membership of organizations. Put most straightforwardly, social movement requires regular action with others. Mapping this through network ties can show which groups and individuals take common action and exchange ideas and resources and, conversely, those that are nominally part of the movement, but are in fact inactive or marginal. This means that we can also distinguish central and peripheral actors in the movement. A focus on networks also means that there is no single type of organization that defines a social movement (Diani 2003). Movement organizations can be hierarchical and centralized, or the opposite. And, as in the environmental movement, and the transnational global justice networks examined by Routledge and Cumbers (2009), they can be a combination of both.

A third feature is that at least some parts of a social movement network are involved in public protest, which we regard as essential to the public political dimension of movement action. The fourth feature is that movements challenge some aspect of dominant cultural codes or social and political values. In short, they argue for social and political change that goes beyond policy change (Melucci 1996; Thörn 2006: 11). Social movements are therefore radical, whether they are on the left or on the right. In the social movement parts of the environmental movement, however, the influence of the left-wing heritage has been overwhelming, including in FoEI (Doherty 2002).

This is a complicated definition to apply empirically since we have to apply four criteria separately to actual groups that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: The FoEI Tradition

- Part III: How FoEI Works

- Part IV: Conclusion: Unity without Uniformity

- Appendix: Categorizations of FoE National Groups, 2007

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index