eBook - ePub

Philanthropy and Education

Strategies for Impact

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Philanthropic foundations play an increasingly important role in attempts to enhance the performance ofschool systems. Based on case studies from Germany, Switzerland and the US, this book develops an innovative model of effective education philanthropyfor successfully tackling problems in the complex field of education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philanthropy and Education by E. Thümler,N. Bögelein,A. Beller,H. Anheier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Negocios en general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Understanding Education Philanthropy

1

Education Philanthropy in Germany and the United States

One of the most significant international trends in education is the increasingly important role of private actors in the improvement of public schools (Meyer and Rowan 2006). International advisory firms, non-profit organisations, corporate social responsibility divisions of commercial enterprises, individual consultants and a growing number of philanthropic foundations have joined the field which used to be almost exclusively government domain (Bethge 2006; Rowan 2006). The public school system is thus becoming an arena where new and old actors meet in order to improve its quality in possibly innovative, often collaborative, and sometimes contentious ways.

In both Germany and the United States, philanthropic foundations and their grantees play an increasingly prominent, powerful and visible role in this context (Czerwanski 2000; Carr 2012; Reckhow 2013). Some of them even aspire to change the whole public school system, or at least large and important parts of it. The Bertelsmann Foundation, for example, “embarked on a broad campaign to fundamentally reform and reposition the German educational system” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2007: 62). In the United States, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation wants to “dramatically improve education so that all young people have the opportunity to reach their full potential” (Gates Foundation 2011). But the actual or potential social change caused by foundations need not necessarily be regarded as beneficial to society, and critics have blamed them for distorting the public system rather than improving it. In Germany, for instance, researchers have claimed that foundations succeeded in gaining major influence on educational policy, aiming at a neo-liberal transformation of the national educational system (Schöller 2006). In a similar and fundamentally critical vein, Saltman (2010) and Kovacs (2011) diagnose the “corporatization” of public schools in the USA by venture philanthropy actors. Moreover, while the public school system has come under attack due to its persistent inability to guarantee a high level of achievement for all students, foundations’ attempts to find a systemic remedy to these and related shortcomings have been portrayed as failures as well (Connell and Klem 2001; Bacchetti and Ehrlich 2007; Lagemann and de Forest 2007; Thümler 2011; Carr 2012). Overall, the discussion on education philanthropy is characterised by a constant tension between diagnoses of very moderate actual achievements, on the one hand, and high-flying ambitions for – or warnings of – systemic change on the other.

This is where the question of social impact comes in. Given foundations’ self-imposed ambitions and societal expectations, the increased engagement in public education is reasonable and meaningful only if philanthropic activities make a significant difference that can be demonstrated empirically and that is actually beneficial to society. It is against this backdrop that we investigate philanthropic initiatives to foster academic learning in Germany and the United States1 during the period of compulsory education.2 These two countries represent fundamentally different national contexts – for instance, a liberal welfare state regime in the US versus German corporatism (Esping-Andersen 1990: 26–27) – and their educational systems, as well as their non-profit and foundation sectors, vary widely. But at the same time, there are important similarities that make comparison possible. In both countries the federally organised public school system faces strikingly similar problems and the strategies pursued by public and private actors are also often quite similar. While, in the United States, it is the achievement gap that is in the focus of attention (Carr 2012), German concerns regularly address unjust school structures (Maaz et al. 2010). In both countries, philanthropic actors experiment with different methods to address old problems in new and potentially more effective ways, for instance by pursuing explicitly strategic (Frumkin 2005), entrepreneurial (Gerber 2006; Quinn et al. 2013) or political approaches (Reckhow 2013). Yet, there remains considerable disagreement and uncertainty when it comes to the question of how foundations can successfully and responsibly foster better learning.

For these reasons, philanthropic practice might benefit from a better understanding of what foundations can and should aspire to achieve, and by which means. Taking a closer look at one of the central fields of philanthropic activity also promises to contribute to the discussion of some of the most persistent themes in the research on philanthropy, such as public accountability, the responsiveness to societal needs and the potential to live up to increased expectations of stakeholders (Harrow and Jung 2011: 1049). Furthermore, the scientific relevance of philanthropic attempts to improve public schools goes well beyond the limited field of the study of philanthropy. Scholars of educational organisations have demanded that the diverse actors of the “school improvement industry” be increasingly taken into consideration to sharpen our overall understanding of change processes in the organisational field of schooling (Rowan 2006: 78–79). Moreover, the study of education philanthropy is of importance when it comes to the analysis of planned school improvement. Today our knowledge of the factors that drive or prevent these processes is still too limited, particularly in Germany where school effectiveness research was neglected in the decades before the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) first Programme of International Student Assessment (PISA) study (Bonsen et al. 2008). The investigation of education philanthropy may simultaneously provide important empirical data, as well as offer new insights into the structures and mechanisms relevant for the success or failure of reforms.

1.1 Rationales and realities of education philanthropy

Education is one of the most relevant fields of action for both German and American foundations (Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen 2012; The Foundation Center 2010). In the last decades, countless activities have been launched, primarily addressing children and youth as a target group. It is easy to see why this is the case: At first glance, philanthropic commitment to education offers enormous advantages. Firstly, it promises to positively influence the whole lives of young people as interventions3 take place at a time when change for the better is still feasible and comparatively easy. Moreover, enhanced success in learning may set the course for more positive trajectories throughout the rest of students’ lives. Secondly, education is regarded to be of crucial societal relevance by virtue of training the workforce of the future, enabling active participation in society and working towards societal coherence by securing individual inclusion (Fend 2008). Thirdly, as a consequence, education is a field that enjoys considerable public reputation and awareness; attempts to, for example, foster individual processes of learning or improve the performance of schools can expect to gain applause and support from public audiences, as well as from professional stakeholders, parents and students (Hess 2005b: 10).4

To talk about the enhanced education of the young generation means to talk about schools. Due to compulsory education laws, the vast majority of children and youth between 1st and 9th grade attend formal schooling, rendering schools the dominant educational institution in contemporary Western societies. Even those philanthropic activities that take place outside of schools usually aim at furthering academic success. This propensity is mirrored in research on education philanthropy. It almost exclusively addresses attempts to enhance the performance of public schools.

This focus on schools has manifest advantages. In countries like the United States and Germany, foundations deal with more or less uniform educational administrations, which can be helpful with regard to access to the system, transparency of regulations and reliability of operations. Furthermore, there is a considerable organisational infrastructure endowed with extensive knowledge related to schooling and school reform that can be instrumental in developing or implementing programmes. Foundations also have the opportunity to draw on a huge body of scientific knowledge and expertise on schools, school development and methods for evaluation. Finally, while schools are not necessarily publicly run, public budgets in both Germany and the United States are by far the dominant source of school funding (OECD 2012). Hence, if foundations were successful in enhancing the performance of the public school system or publicly financed private schools, this would promise enormous leverage effects.5 Take, for instance, philanthropic resources invested in the “turnaround” of a badly performing school. While the intervention itself might be relatively limited – solely focussing on the process of change – in case of success, it might result in sustained benefits to thousands of students over time, with the organisation being run and financed by the state. As an effect, education is, at least in theory, a particularly tractable field of action.

At the same time, work in the field of education confronts foundations with considerable problems and, depending on the perspective one takes, the very aspects that speak in favour of education might also be seen as drawbacks. First of all, the societal relevance of education is not least due to the massive size of target group and system. In the USA, 54.7 million students were enrolled in 132,183 elementary and primary schools in 2011/2012 (Snyder and Dillow 2012), in Germany, 11.4 million students were enrolled in 34,528 schools (Statistisches Bundesamt 2012a, 2012b).

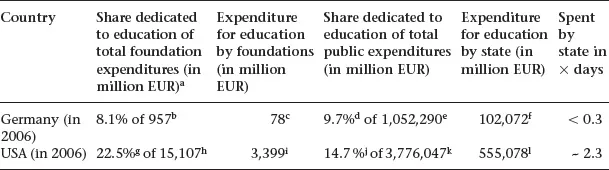

While a considerable share of philanthropic resources has been invested in education over time, foundations in both Germany and the United States remain marginal actors in relation to the magnitude of the public system. To illustrate this claim by a comparison of budgets: In the United States, the overall sum of foundation expenditures in the field of education in a whole year is spent by the state in little more than two days, whereas in Germany it is spent in eight hours (see Table 1.1 below).

What is more, when it comes to the reform of public schools, foundations are confronted with a very large, highly complex and thoroughly institutionalised social and political system. Schools are influenced by a multitude of different stakeholders on a local, national and international level, and governing the system is all but straightforward (Altrichter and Maag Merki 2010). Furthermore, schools assign or withhold social status, grant or deny access to higher education and set the course for more or less favourable professional careers. By virtue of this function, schools become objects of the interests of powerful groups in society. While, in principle, they open up pathways for social advancement through academic achievement under conditions of unequal social structures in Germany, as well as in the United States, schools are not, and probably can never be, refuges of equal assessment and fair distribution of opportunities based on performance only. At the same time, their structures and processes, techniques and curricula are deeply embedded in national traditions and cultures (Friedeburg 1992: 471). As a result,

Table 1.1 Expenditures for education by foundations and the state

Note: a Amounts in US$ converted to Euros according to the average exchange rate in 2006: 1 Euro = 1.26 US$ (Deutsche Bundesbank 2013).

b Based on total expenditures of the top 50 German foundations that represent an estimated 1/3 of the value of all charitable foundations in Germany excluding foundations that generate revenues by running institutions (in German “Anstaltsträgerstiftungen”) according to an internal research report of the Centre for Social Investment.

c All education programmes, except science sponsoring.

d The World Bank (2013).

e OECD (2009: 457).

f Includes government spending on educational institutions (both public and private), education administration, and subsidies for private entities (students/households and other privates entities) (The World Bank 2013).

g The Foundation Center (2008).

h The Foundation Center (2008).

i All education programmes, including policy, management, and information, elementary and secondary, vocational and technical, higher education, graduate and professional, adult and continuing, library science/libraries, student services, educational services (The Foundation Center 2008).

j The World Bank (2013).

k OECD (2009: 457).

l Includes government spending on educational institutions (both public and private), education administration, and subsidies for private entities (students/households and other privates entities) (The World Bank 2013).

[e]ducation is the most “upstream” of all social endeavours, closest to the point at which a nation’s cultural and institutional orthodoxies originate. Their upstream location makes educational institutions perhaps the most change-resistant among the large-scale public institutions, simply because they are supported by the deepest sentiments of tradition, habit, and identity held by the largest number of people. (Meyer 2006: 219)

Thus, while education is crucial to society, it is at the same time an organisational field characterised by a high degree of inertia and persistence. Moreover, the system itself is dependent on socio-economic and cultural preconditions (e.g. the level of poverty in society or distributions in power) that are entirely beyond its scope (Friedeburg 1992; Tyack and Cuban 1995).

Finally, even the propensity towards favourable public perception and media coverage of innovative activities in education may have unintended consequences (for discussions of the concept, see Merton 1936; Fine 2006). In the absence of a controversial debate and public criticism, it can be very difficult to obtain reliable feedback on the intervention’s quality and progress towards the intended aims, which, in turn, may easily lead to overly confident assessments of the relevance and the impact of one’s own philanthropic activities (Hess 2005b: 9–10; Hess 2005c: 311–312).

As a result, all philanthropic initiatives that aim to create sustainable, meaningful and widespread change are demanding tasks without any guarantee for success, and evidence for systemic improvement as a result of philanthropic action remains elusive (Lagemann and de Forest 2007: 62). For instance, the Annenberg Challenge, a public school reform programme endowed with US$600 million that spread its resources broadly over different sites and for different purposes, is widely regarded as an outright failure. It has frequently been seen as an example of the phenomenon whereby inadequately invested resources may be absorbed by the public system without leaving relevant traceable effects (Domanico et al. 2000; Hess 2005b: 4–5; Lagemann and de Forest 2007: 62; for the opposite opinion, see Saltman 2010: 71–73). Another, more recent instance of failure is the Small Schools Programme: The first major school reform activity of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation6 proved to be “a disappointment” in the eyes of the founder (Gates 2008). Under these conditions, all attempts at enhancing the school system could easily be perceived as “casting buckets into the sea” (Greene 2005: 49) – that is, as contributions so small in size that they pale into insignificance vis-à-vis the problems they address.

Yet, foundations have regularly been portrayed as organisations that are particularly apt, helpful and instrumental in overcoming these difficulties, and in bringing change and innovation to an allegedly sclerotic ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Notes On Contributors

- Part I Understanding Education Philanthropy

- Part II Case Studies

- Part III Analysis

- Index