- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Black Women's Bodies and the Nation develops a decolonial approach to representations of iconic Black women's bodies within popular culture in the US, UK and the Caribbean and the racialization and affective load of muscle, bone, fat and skin through the trope of the subaltern figure of the Sable-Saffron Venus as an 'alter/native- body'.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Black Women's Bodies and The Nation by S. Tate in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Kultur- & Sozialanthropologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Looking at the Sable-Saffron Venus: Iconography, Affect and (Post)Colonial Hygiene

For Saidiya Hartman (2008: 2):

what we know about Venus in her many guises amounts to little more than a register of her encounter with power […] An act of chance or disaster produced a divergence or an aberration from the expected and usual course of invisibility and catapulted her from the underground to the surface of discourse […] We only know what can be extrapolated from an analysis of the ledger or borrowed from the world of her captors and masters and applied to her.

What I am interested in as I borrow ‘from the world of her captors’ is exploring Sable-Saffron Venus as a conscious act of colonial and contemporary white racial hygiene to deal with white male desire, disgust for the Black woman’s body, as well as fear of loss of sovereignty through heterosexual transracial intimacy and concubinage. During enslavement and colonialism, imaging Sable-Saffron Venus became a site of hygiene for white men seeking ‘to go native in the Caribbean’, or forsaking ‘pure white women’ for sex with ‘hot constitutioned’ women always already known as ‘dark temptresses’. As a parody, Sable-Saffron Venus stuck to the bodies of all Black women in the Caribbean. She became a word used as a warning, a mode of disciplining white heterosexual male desire for Black female flesh as much as presenting her body as violable, disposable, a commodity and prostitute. In the zone of exception that was the sugar plantation in the Caribbean, her bare life (Agamben, 1998) made white lives liveable. Like Hartman I seek to ‘revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence’ by trying to understand the heterosexual white male disgust of and desiring fear for Black women’s bodies, which produced those artefacts of Caribbean enslavement iconography: ‘the Voyage of the Sable Venus’ as both ode and image, the painting ‘The West Indian Washerwomen’ and the satire ‘Johnny Newcome in love in the West Indies’. Their reading will lead into thinking about who can come into the circle of meaning through representation as the chapter revisits Truillot’s (2003) alter/native by charting the emergence of the Sable-Saffron Venus as muscle, bone, fat and skin, which we see reflected in the bodies of Saartje Baartman, Josephine Baker, Grace Jones, Beyoncé Knowles, Rihanna and Naomi Campbell. First, let us move to historicizing the Black woman’s body as fetish object.

The Black woman’s body as fetish object – the Black Venus and desire

During the Middle Ages, (1119–1142) the religious scholar Peter Abelard, wrote to Hélöise on the Song of Songs and the Ethiopian, the Queen of Sheba, being chosen for the King’s bed, ‘besides, it so happens that the skin of black women, less agreeable to the gaze, is softer to touch and the pleasures one derives from their love are more delicious and delightful’ (Sharpley-Whiting, 1999: 1). He wrote in the Middle Ages about Blackness, the nature of Black female sexuality and bodies in a way which still resonates today. These were the beginnings of the sexualization of Black women that found a place among France’s 19th-century male literati and the rest of Europe (Sharpley-Whiting, 1999). Black women have long occupied a space in which their bodies are always marked as abnormal objects of white male desire so as to construct those bodies within a politics of exceptionalism (Beckles, 1999). As such the sexual use of a Black woman did not mean that the act was about intimacy or that it removed abnormality from the Black woman’s body as reasons for this exception could be found. The uses and abuses of the Black woman’s body does not end there as it has become a fetish object which provides an essential texture for the production of the white US American/European woman’s body. Indeed, for Hortense Spillers (1987: 65) speaking from the position of Black women’s bodies:

Let’s face it. I am a marked woman, but not everybody knows my name. ‘Peaches’ and ‘Brown Sugar’, ‘Sapphire’ and ‘Earth Mother’, ‘Aunty’, ‘Granny’, God’s ‘Holy Fool’, a ‘Miss Ebony First’, or ‘Black Woman at the Podium’: I describe a locus of confounded identities, a meeting ground of investments and privations in the national treasury of rhetorical wealth. My country needs me, and if I were not here, I would have to be invented.

If Black women were not here they would have to be invented so that ‘the white woman’s body’ as norm could come into being. We see this, for example, in the European fascination with the Hottentot Venus (Yancy, 2008; Hobson 2005; Gilman, 1992) and Grace Jones, the French embrace of Josephine Baker, the body of Sasha Fierce as the curvaceous Black ideal/stereotype, our love of Oprah Winfrey who as a ‘raced’ yo-yo dieter displays the fat Black woman’s body which as anti-Mammy seeks respectability through reigning itself in, as well as the svelte supermodel body of Naomi Campbell. We still see European/US Africanism linked to the perception of white Europeans/US Americans as racially superior in the body of Sasha Fierce as Sapphire/Jezebel. Indeed, Sasha Fierce might be the embodiment of 21st-century re-imaginings of the Hottentot Venus if one notices the sexualizing focus on her body as ‘booty’ and breasts in such DVDs as ‘Videophone’ and ‘Single Lady’ as well as her publicity shots. For Janell Hobson (2005: 7) ever ‘since nineteenth century popular exhibitions in Europe of South African women with so-called steatopygia, black female bodies have been fetishized by this feature and identified with heightened sexuality and deviance’. This statement relates to the white gaze, however, because as Black cultural insider Hobson (2005: 2) also notes ‘[…] from a black cultural viewpoint, to not be endowed from behind is to be “lacking” in some way’.

The name ‘Venus’ is not a form of praise. Venus was the protector of Rome sex workers who erected a temple in her honour where aspiring courtesans were taught the arts of love (Yancy, 2008). The use of ‘Venus’ to describe Baartman, amongst others, locates Black women’s bodies as those of sex workers, as ‘loose’, which invokes white moral, sexual and racial superiority (Yancy, 2008: 95). Prior to Baartman, the ‘Sable Venus’ and her Black-white ‘mixed race’ sister/daughter ‘Saffron Venus’ were constructed in the Caribbean. ‘Saffron’ makes us think of both the colorant/spice and the food that is consumed, The word ‘sable’ means both a very dark colour and a small animal with thick fur that is used for clothing and artists’ brushes. In ‘sable’ we see the link between animality and racial othering characteristic of white discourse on Africans whose enslaved bodies were consumed in the fields and in sexual and domestic services on Caribbean plantations. Sable Venus’s 18th-century representation in the poem The Sable Venus: An Ode by Isaac Teale (1765) sexualized, exoticized and othered all African descent women represented as willing and submissive sexual partners. It erased enslavement’s daily brutality, the horrors of the Middle passage and the white benefits from the slave trade in the Caribbean itself (Bush, 2000) as we can see in this brief excerpt

O Sable Queen! Thy mild Domain

I seek and court thy gentle reign

So soothing, soft and sweet.

Where meeting love, sincere delight

Fond pleasures, ready joys invite,

And unbrought raptures meet.

Do thou in gentle Phibia smile,

In artful Benneba beguile,

In wanton Mimba pout

In sprightly Cuba’s eyes look gay

Or grave in sober Quasheba

I still find thee out

The Englishman Teale, was employed as a teacher in the ‘learned languages’ by Zachary Baily, the uncle of the then 22-year-old Bryan Edwards who would go on to be a Caribbean historian and vociferous supporter of slavery (McCrea, 2002). The Ode ends with all of Jamaica, particularly the people of quality, from Port Royal, Spanish Town and Kingston, coming to greet the Sable Venus on her arrival in the island and the poet declares his utter devotion to her whether she appears as Phibia, Benneba, Mimba, Cuba or Quasheba. These were all names of African enslaved women at the time (McCrea, 2002). Although it was an English-Jamaican creation the ode was widely circulated and influenced 18th- and early 19th-century pro-slavery mind-sets. For example, the ode was reproduced in Bryan Edwards’ (1794) book further aiding its circulation. In Book 4 we see Edwards’ (1794: 26) attempt at white colonial racial hygiene as he addresses his audience through the satire of poetry on the folly of white male paramours in the Caribbean, when he says:

I shall therefore conclude the present chapter by presenting to my readers, a performance of a deceased friend in which the character of the sable and saffron beauties of the West Indies and the folly of their paramours, are portrayed with the delicacy and dexterity of wit, and the fancy and elegance of genuine poetry.

One wonders, though, if the ode was not also a warning to Edwards himself from his teacher as Teale concludes

Should then the song too wanton seem,

You know who chose th’ unlucky theme

Dear BRYAN, tell the truth

(Edwards, 1794: 33)

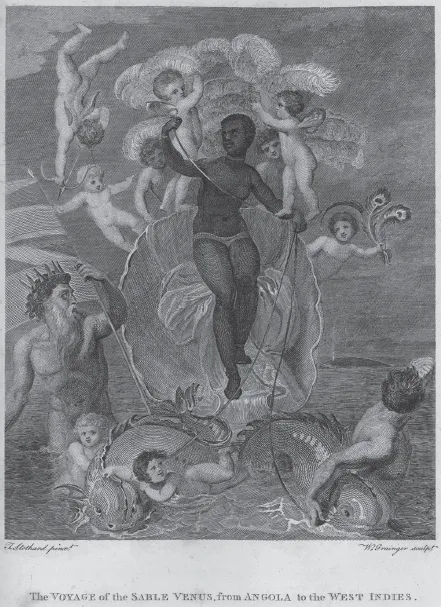

The ode led to the response of the painted illustration The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies (Figure 1.1) by Thomas Stothard and its engraving by William Grainger (McCrea, 2002) which appeared as an illustration in Edwards (1794: 27).

Stothard’s The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies (1793) is a satirical reference to Boticelli’s Venus transferred to the slave trade (Mohammed, 2007). If we juxtapose the bodies of the two Venuses we see that the Sable Venus has a more curvaceous (more bottom) and muscular body – biceps, trapezius and quadriceps – than Boticelli’s Venus who looks barely pubescent, with no muscle tone to speak of, slender limbs and barely visible hips. The Sable Venus is being declared to have a body which is both productive as a labourer on the plantations and reproductive as a site of sexual pleasure and bearer of children to be enslaved. While the whereabouts of the painting of the Sable Venus is unknown, the image survives in Edwards (1794) and in William Grainger’s engraving in the British Museum. The Sable Venus was placed in a ‘Sea Triumph [so] Stothard appeared to have ensured that his black African slave would be ensconced within an old mythological “topos” which had become an established feature in British visual iconography’ (McCrea, 2002). The Sable Venus emerged from the sea with a shell as the vessel of transportation. She had gods and cherubs who protected her on her journey across the Atlantic. This image of a Black woman in motion relates to the public triumphal spectacle that existed since Graeco-Roman times. However, the painter/engraver does not conceive the Sable Venus as a ‘Venus’ but as Rafael’s Galatea who rides in a cockle shell and is pulled by dolphins. This means that the Sable Venus did not have the same status as the goddess Venus because she was a Neried and a sea-nymph (McCrea, 2002). Her ‘race’ put her below the white Venus in terms of status. Further, the horrors of the Middle Passage are re-presented as a version of the birth of Venus because the slave ship, with its brutality, rape, murder and deprivation is transformed into a shell, while dolphins replace deadly sharks ready to consume African bodies whether dead or living (Mohammed, 2007).

Figure 1.1 The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies

Courtesy of the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.

Both Teale’s poem and Stothard’s painting were used by Bryan Edwards (1794), to support the slave trade by diminishing its barbarities and those of plantation life for the enslaved. By drawing on these two sources he implies that there has been a rebirth of European culture in the Caribbean through the idea of the rebirth of Boticelli’s Venus. Further, he erases the decimation of the original inhabitants and denies the ravages of the enslavement of African women (Mohammed, 2007). This denial is also accomplished by placing the Sable Venus’s origin in Angola which was not a British colony but a Portuguese one. However, it was well known that the West Indian planters preferred people from Angola and the Congo to Coromantees from the Gold Coast because they were cheaper and supposedly ‘less resistant’ to enslavement. The poem and the painting rendered the Sable Venus suitably ‘European’ for white men, represented as FRANK, Spaniard, Scot and English, who would eventually exploit her even though planters like Edward Long (1774) thought she looked like an ape.

Bryan Edwards (1743–1800) retired to England in 1792. He was a member of the West India Lobby and was an opponent of the abolition of slavery. His publication established him as a serious historian of British colonial history and West African slavery and was used by both pro- and anti-abolitionists. In 1794 the book was translated into German and in the second edition in 1794 the image of the Sable Venus appeared illustrating the poem (McCrea, 2002). It is unclear if the engraver replicated the essential details of the original painted-illustration (McCrea, 2002). However, what is more pertinent is the sexualizing European male gaze which produced the Black woman as Sable-Saffron Venus.

For Patricia Jan Mohammed (2007: 7), if ‘you were to look again closely at both Venuses, although the Sable Venus holds the strings of the sea horses, it is not a free flowing lock of golden hair which decorates her neck like that of the Boticellian counterpart, but a decorously placed slave band’. Although McCrea (2002) asserts that this is a pearl necklace, the Sable Venus was decidedly un-free even if she wears a loin girdle of precious stones and ankle amulets, revealed by her robe which has fallen to the base of the car (McCrea, 2002). The muscularity exposed by her de-robing points to her as a worker, different from the white women who were her betters. The Sable Venus was clearly part of the regime of colonial visibility which discursively constructed, positioned and disciplined Black women’s bodies in order to generate a coherent and seemingly consensual image of social relations based on white male, heterosexual domination.

McCrea (2002) suggests that Stothard may have used the antique cast at the Royal Academy as the basis for the Venus as female models were regarded with suspicion even though there were no rules for the use of Black female models at the time. The bodies of both the Botticelli and Sable Venuses are represented as decidedly not fat. Indeed, Boticelli’s Venus is recognizably slim by contemporary standards. Therefore, the European standard impacted on Black women’s bodies in an anatomical economy in enslavement societies in which being ‘attractive to white men’, which could be translated as not being fat, but being nonetheless curvaceous, could potentially have life-changing benefits. The clear reverse of this is that Black enslaved women had to be represented as beautiful in known ways – that is, slim with pert breasts and large buttocks – so as to continue the fiction of white men as naive dupes who succumbed to their powers of seduction. Other representations of Black women at this time were ‘she devil’ who resisted the sexual and economic needs of white men and passive ‘asexual drudges’ (Bush, 2000). We can speculate that their depictions would have been far different from that of the Sable Venus. The depiction of the ‘she devil’, for instance, would most possibly be as muscular and defeminized as was the case for Nanny the Maroon leader and a Jamaican National Hero, whereas ‘passive asexual ‘drudges’ most possibly would have been represented as fat and, therefore, undesirable as was the case for Mammy in the USA. The point of this speculation is to make it clear that body shape, size, musculature as well as skin colour linked to Black women’s place in the anatomical, productive, reproductive and affective economies of enslavement society and the value placed on some bodies and not others. Further, the Boticelli Venus’s slight curves/pert breasts/rounded stomach/slim norm which cuts across Europe, the Americas and the Caribbean as a desirable body type is not new but clearly has a long history in our Global North West bodily imaginaries.

The Sable Venus ‘represented white male erotic fantasies, but also the widespread practice of concubinage and sexual exploitation of black women’ (Bush, 2000: 762). Concubinage was a survival strategy for younger enslaved women and demands a deconstruction of the white English representation Sable-Saffron Venus as tempting, scheming, wanton and non-labouring slave body who was always prepared to lead white men astray because of her dangerous hyper-sexuality (Bush, 2000). The rape and coercion of Black women was paradoxically represented as a triumph of the Venus over the slave owners and slave traders within Teale’s poem and within plantation enslavement societies. There emerged in the Caribbean as elsewhere a white fetishization of Black women as an element of white masculinist culture (Bush, 2000). We see this masculinist view of Black women and white men’s right to their bodies repeatedly in Teale’s poem as the Sable Venus is presented almost pornographically as beautiful, beguiling, prostitute:

Her skin excelled the raven plume,

Her breath the fragrant orange bloom,

Her eye the tropic beam:

Soft was her lip as silken down,

And mild her look as evening fun

That guilds the COBRE stream

The loveliest limbs her form compose,

Such as her sister VENUS chose,

In FLORENCE, where she’s seen;

Both just alike, except the white,

No difference, no – none at night,

The beauteous dames between

This construction prevailed even within the deeply significant African-centred womanist culture which existed during enslavement and which only became partially supplanted by masculinist culture since emancipation (Bush, 2000). Indeed, it ‘was the existence of such a culture which arguably prevented white men from ever gaining the full measure of black women, even those whom they supposedly knew intimately through concubinage’ (Bush, 2000: 776). Thus, enslaved women should not be seen as helpless victims but as women who had some measure of control over their own sexuality and that of their owners (Mohammed, 2007). As a strategy of survival, relationships with white men could offer better treatment for Black women and their Black-white ‘mixed race’ children as well as some material gain through, for example, independent ‘business’ activities like huckstering – small-scale market...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction – Iconicity: Black British Women’s Bodies as (In)Visible Spectacles

- 1 Looking at the Sable-Saffron Venus: Iconography, Affect and (Post)Colonial Hygiene

- 2 Batty Politics: Desire and Rear Excess

- 3 When Black Fat Does Not Signify Mammy: Disparagement Humour and Sexualization

- 4 Fascination: Muscle, Femininity, Iconicity

- 5 Pleasure Politics: The Cult of Celebrity, Mullatticity and Slimness

- 6 Skin Lightening: Contempt, Hatred, Fear

- 7 Coda – Decolonization and Seeing through Black Women’s Bodies

- Bibliography

- Index