- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Illustrates how decision-making in organizations has to go beyond economic criteria and the individual level, due to the impossibility of making decisions that do not affect other human beings. The author reviews the conventional analyses of decision-making that do not take into account how decisions affect others and suggests an alternate model.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Decision-Making in an Organizational Context by J. Rosanas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Personal Decisions Where Other People Are Far Away

1

The Lotteries of Life: Decisions about an Uncertain Variable

If anything about this world is certain, it is that it is uncertain. We are constantly faced with uncertainties, which are often described as “lotteries”. Any happening or process that is, or appears to be, determined by chance is called a lottery. In soccer, for instance, the well-known method of five penalty kicks for each team to decide which team wins when the game has ended in a tie (what FIFA calls the “penalty shoot-out”) is often informally called the “penalty shoot-out lottery” to imply that chance, or randomness, plays an important role in its resolution. We use the same term to refer to more everyday situations, such as whether or not we will be chosen for a particular job, or whether we will be able to avoid heavy traffic on our drive back into the city after a long weekend. Events such as these are not really lotteries, but we use the term to indicate that they depend critically on “luck”, i.e., on factors beyond our control that we do not understand too well, as happens in real lotteries, where winning depends exclusively on which ball comes out, which in turn depends on a multitude of small factors that we cannot foresee. On one occasion, in a certain lottery that was broadcast on TV, it was discovered that some balls had less chance of dropping out of the machine because they were closer to the spotlights, which made them hotter, causing them to dilate, so they were less likely to pass through the exit hole. The organizers had to take steps to ensure that this did not happen, so that the draw depended solely on “luck”, i.e., what we do not understand and cannot control. Factors “small” as a possible uneven heating of the balls due to other unforeseen and unforeseeable circumstances are shaping the probability of a particular event we consider random. It is when we say that the event depends on “luck”.

In this sense, then, “luck” is what does not depend on us humans, even though the example of the balls warmed by the lights reveals how human intervention can wittingly or unwittingly deflect “luck” one way or the other. A real lottery is intended to be such that the a priori probability of any number, or combination of numbers, is exactly the same as that of any other, thus eliminating factors that systematically favor one outcome over another.

Often we wish a friend “luck” when she must face a difficult situation. We accept that there are factors that are beyond our friend’s control, but we hope that they will be in her favor. We take for granted that the result depends partly on her, and partly not. The ancient Greek Stoics (Zeno and his followers) were aware of this; they said that to show fortitude (one of the fundamental virtues) was to accept what could not be changed, improve what could be changed, and have the wisdom to distinguish between the two. Distinguishing between what can and cannot be changed is indeed crucial to the success of our actions. If we battle to change what cannot be changed, we are banging our heads against a wall. And if we neglect to change what can be changed, we deny ourselves a benefit and renounce our nature as rational beings.

The real world, however, makes this difficult for us. That is why the Stoics insisted on the scientific view, i.e., the need to know the laws of nature. By investigating the laws of nature we can avoid disappointment and waste of effort. In the gray areas, we are bound to get confused: we may settle for something bad (or not good enough) that could be changed, or we may try to achieve something that is actually impossible. The problem is how to know what can be changed. In case of doubt, therefore, it seems sensible to try.

There is a famous (possibly apocryphal) anecdote that Napoleon, in choosing an officer for a particular military mission, passed over a general who all his advisers told was very competent because he had heard that this general had been unlucky in several of his military missions, in his marriage, in business, and in gambling. “Too much bad luck”, Napoleon is said to have remarked, “better to appoint someone luckier”.

This anecdote may be a token of superstition, or it may have been the Emperor’s opinion that when a person is persistently unlucky, it is because he does not know when to persist and keep trying. In popular speech it is said that “you make your own luck”. Today’s “positive psychology” argues that optimism brings good luck, i.e., simply believing that we can do something improves our chances of actually doing it. We will come back to this later, but to go deeper we first need to consider what happens, and what a person should do, when faced with sheer “luck”, i.e., factors beyond her control. Perhaps the best examples of such situations are precisely true lotteries.

How to play a lottery … if you must

Lotteries are often used by governments to raise money, hence the humorous definition of lottery as “a voluntary tax paid by those who do not know probability theory”. In the casinos of Las Vegas there is a saying that whenever a customer is winning at roulette, her gains are in fact a temporary loan from the casino, which she will repay with high interest.

It should be obvious that if casinos make a profit and governments organize lotteries to raise revenues, it is because someone always loses. And that someone is none other than the customers, players, gamblers, or whatever we choose to call them. Playing roulette or any lottery therefore seems quite irrational.

Yet something drives many people to do so, sometimes reaching the level of a serious addiction. That is why casinos and lotteries exist. The fact that the Christmas lottery in Spain (with a very large prize, called El Gordo, The Big One) has become a festive tradition, seen as wholly positive and innocent, demands an explanation. In principle, buying a stake in something where we have such high chances of losing should surely be considered irrational, shouldn’t it?

The casual buyer of lottery tickets tends to give two kinds of reasons for her behavior: “Someone has to win, and it could well be me”, and “If I win, I’ll have a fortune, whereas if I lose, it’s just a few euros, so I won’t be any worse off.” We will see later how the former is essentially a poor assessment of a small probability, and the latter a poor assessment of the cost of playing lotteries.

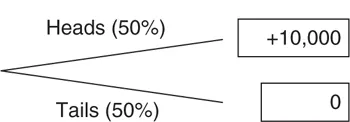

First, however, we must analyze the problem from the beginning. To do that we must invite the reader to consider a relatively simple (and perhaps somewhat unrealistic) lottery. Suppose we offer someone a ticket for a heads-or-tails lottery, with a perfectly legal, balanced coin, so that the chances of getting either heads or tails are equal. If the coin comes up heads, the bettor wins €10,000, otherwise nothing. The possibilities are shown in Figure 1.1.

If you ask anyone who is not an expert in the subject whether she would be willing to pay €5000 for a ticket for this lottery, she is unlikely to say yes. Hardly anyone will be willing to pay more than, say, €2000, and that too only if the person is fairly wealthy. Anyone who struggles to make ends meet will only be willing to pay considerably less.

Figure 1.1 Example of a simple lottery

And anyone with a basic grasp of probability theory, or a knowledge of gambling, will first want to know whether the game is to be played once or repeatedly. If it is to be played repeatedly, they may be willing to pay more (though not as much as €5000). Why is that? Well, let’s say a person plays the lottery 100 times. She would get about 50 heads and 50 tails, and so would win the prize 50 times out of 100. As the player has to pay €5000 each time she plays, her winnings would be zero:

Prize for 50 heads: 50 × 10, 000 = 500, 000

Total cost of participating in the lottery 100 times: 100 × 5000 = 500, 000

So if a player gets 50 heads, she will not win anything; but if she gets less than 50 heads, she will lose. The reason why most people would want to pay substantially less than €5000 to take part in the lottery is to cover this possible loss. If someone were to buy 100 tickets at €4000 per ticket, for a total of €400,000, she would only need to get 40 heads to make a profit. As the probability of getting fewer than 40 heads is fairly small, there is no loss to be covered at that price. In contrast, the probability of getting between 40 and 50 heads, though not very high, is by no means negligible, so there is a real chance of making a profit.

Of course, if a player gets exactly 50 heads, she will win €100,000. That is what happens on the average, so one has a reasonable chance of winning €100,000 and a very high probability of not losing. And of course, if a player gets more than 50 heads, her gains will be even larger. In fact, the probability of getting between 50 and 60 heads is exactly the same as that of getting between 40 and 50, i.e., not very high but far from negligible.

In order to play this game confidently and rationally, however, a player must have some initial wealth to fall back on, just in case. If you had a run of “bad luck” at the beginning and got a lot of tails, your investment would be steadily increasing. So if you do not have the necessary financial means at your disposal, you will have to leave the game before your “luck” turns.

The amount a bettor would win “on the average” (€5000 in our example) if this lottery were played many times is known as the lottery’s expected value. And it follows from the foregoing that, in general, the amount most people would be willing to pay to participate in a lottery is below the expected value. People who share this preference (which is to say the vast majority of human beings in their right mind) are said to be risk-averse. In other words, they prefer to forego a possible profit, on the average, in order to avoid a possible loss. The maximum amount a person is willing to pay in order to participate in a lottery, i.e., the amount at which the person is indifferent between playing the lottery and not playing it, is called the certainty equivalent of the lottery. The certainty equivalent depends on each person: each person has her own degree of risk aversion, and the lower a lottery’s certainty equivalent, the higher the person’s risk aversion. Thus, a person who is indifferent between playing the lottery and having €1000 for sure will be more risk-averse than another person who is indifferent between playing the lottery and having €2000 for sure. For any given person, then, the difference between the expected value and the certainty equivalent is a measure of risk aversion.

Of course, a person can consistently be a risk lover, i.e., indifferent between the lottery and, say, €6000. In that case, the difference between the expected value and the certainty equivalent may be negative. This occurs very seldom, however. Experimental cases where this seems to occur are more easily explained in terms of limitations to the subjects’ logical reasoning ability (bounded rationality) than in terms of risk loving.

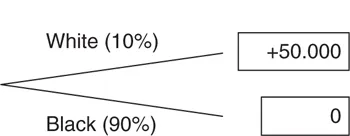

If the probability of winning gets smaller and smaller but the expected value remains the same because the prize increases proportionately, the maximum amount people are willing to pay to participate in the lottery will naturally be less and less. Consider, for instance, a lottery in which a ball is drawn at random from an urn with nine black balls and one white one, with a prize of €50,000 if the ball is white and zero if it is black (see Figure 1.2). The expected value is the same as in the previous lottery, i.e., the average winnings are €5000 per draw (10% of €50,000), but most people will be unwilling to pay as much for participating in this lottery as in the previous one, since the risk is greater: 90% of the time they will win zero and so will lose the amount they paid in order to participate.

Figure 1.2 The same lottery with different probabilities

And so on and so forth, one would expect. This means that the number of people that are willing to pay in order to participate in a lottery will diminish as the probability of winning decreases. There are some exceptions, however.

Not wishing to go into complex technical details, let’s look at this by analyzing a simplified version of the Spanish National Lottery, where there are 100,000 balls. The probability of drawing any specific ball is 1/100,000, and the prize is €10,000,000, so the expected value of this lottery is €100 (i.e., 10,000,000/100,000). Would anybody be willing to pay more than €100 to play? According to the above analysis, the answer should be no. In reality, however, the answer is yes: large numbers of people pay €200 for a ticket in such a lottery. The government sells 100,000 numbers, keeps half of the receipts, and pays out the rest in prizes. So the government keeps its share and the citizens can dream of being rich for a few days (all except one, i.e., who really does get rich!).

The way citizens behave in relation to lotteries is an anomaly, however. Theory offers various possible explanations. Perhaps the most immediate is that people are risk-seeking (rather than risk-averse) where small amounts are involved. As the real explanation lies in people’s intentions and not even they can tell us their true intentions, we will never have a conclusive explanation. But we can still venture various hypotheses, two of which are particularly interesting. We shall look at them next.

The first explanation is that people tell themselves, “the prize must go to someone [so it could be me]”. True, but the odds are so vanishingly small that it is hardly worth trying. But human beings do not know how to deal with very small or very large numbers that lie outside their immediate experience. It is very difficult to get an intuitive sense of what it means to have a chance of one in 100,000 (which is the chance of winning the big prize in the Spanish National Lottery); and it is even more difficult where the chances are one in 14,000,000 (as in 6/49-type lotteries). If I were told that that is the probability of dying in a road accident on a particular trip, I would probably take the car without hesitation. But if I were told that it is the probability of winning the big prize in a lottery, I might buy a ticket “just in case”. This is a benign form of irrationality, although it can become malignant in cases of addiction. An example is the protagonist of Dostoevsky’s novel The Gambler, who always tells himself, “this time I’m going to win”, i.e. he distorts probability, which can be measured objectively, to persuade himself that he has much a better chance than he actually does.

The second explanation is that people underestimate their investment in the lottery. One euro, or even twenty euros, is a small amount that will not get us out of trouble in any circumstances, whereas ten million euros would solve our problems for the rest of our lives. If we played only once, this argument might be acceptable; but it breaks down when buying lottery tickets becomes a habit. Because if you add up every euro spent over a longer period, you will find you have invested more than you would ever have dreamed of investing.

Despite their popularity, lotteries are an anomaly. In normal life people are typically risk-averse and will not risk more than a fraction of the expected value of the prize.

Having titled this section “How to play the lottery”, however, we cannot disappoint our readers. So here are some tips.

The best tip, of course, is not to play; or if you must play, to do so only sporadically, without risking large amounts. “Playing the averages” is a losing strategy; in fact, it is the essence of lotteries and the reason why governments and private operators organize them. It is worth trying to visualize the probability of winning: in a lottery with 100,000 numbers, for example, imagine a huge drum with 99,999 black balls and 1 white ball, from which 1 ball is drawn at random after the drum has been rotated to mix them well. The sight of such a device would very likely discourage many lottery players. And in a 6/49 lottery you are likely to win the big prize every 140 times you win the big prize in the other lottery, which we already saw is a very remote possibility. No further comment is needed. Or perhaps, the only comment worth making is that the small secondary prizes that most lotteries have merely serve to persuade players that winning is not so difficult after all, even though winning the big prize remains extremely unlikely.

If despite everything we disregard this advice and play the lottery, we should at least think carefully. One often hears arguments along the lines of “I have three or four tickets for the Christmas lottery, with different numbers, so I have more chances of winning a prize.” This is absurd! If we love risk but want to play rationally, we should spend all the money we plan to spend on the same number (assuming this is the kind of lottery where you can spend as much as you like on any given number, as in the Christmas lottery in Spain). The risk that you will lose the whole amount increases; but if you are a risk lover, that is precisely what you want: m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Purpose and Structure of the Book

- Part I: Personal Decisions Where Other People Are Far Away

- Part II: Personal Decisions Where Other People Are Near

- Notes

- References

- Index