eBook - ePub

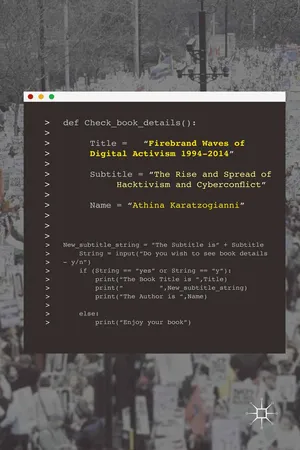

Firebrand Waves of Digital Activism 1994-2014

The Rise and Spread of Hacktivism and Cyberconflict

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Firebrand Waves of Digital Activism 1994-2014

The Rise and Spread of Hacktivism and Cyberconflict

About this book

This book introduces four waves of upsurge in digital activism and cyberconflict. The rise of digital activism started in 1994, was transformed by the events of 9/11, culminated in 2011 with the Arab Spring uprisings, and entered a transformative phase of control and mainstreaming since 2013 with the Snowden affair.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Firebrand Waves of Digital Activism 1994-2014 by Athina Karatzogianni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Origins and Rise of Digital Activism (1994–2007)

1.1 First phase (1994–2001): the origins of digital activism

Knowledge communities and the FLOSS movement

I place the birth of digital activism in virtual knowledge communities, particularly those used to create alternative software products engaging in peer production, as starting with the free/libre/open software movement. They descended from the first hackers of the 1960s: the first dreamers of the power to divert technology from its original purpose to extend it and make it do the impossible.

And yet there is a very long line of lineage in the human condition tracking back in time to knowledge networks at the forefront of human innovation. Ancient Athens was an innovative democracy before the hegemonic decline brought about by the domination of the polis by warfare (Karatzogianni, 2012a). In the cited work, I offer Ober’s analysis from Democracy and Knowledge: Innovation and Learning in Classical Athens (2010), and it is worth reusing that material here. Ober puts forward the hypothesis that democratic Athens competed successfully over time against hierarchical rivals:

because the costs of participatory political practices were overbalanced by superior returns to social cooperation, resulting from useful knowledge, as it was organized and deployed in the simultaneously innovation-promoting and learning-based context of democratic institutions and culture. (37)

Various intriguing arguments stemming from social network and organizational theory are utilized by Ober to understand the superiority of the Athenian system. For instance, process innovation, highly valued by knowledge-based organizations, is thought to be impeded by hierarchies, as they favour learning as routinization at the expense of learning as innovation, which is paramount in highly competitive environments (ibid., 106). The Athenian system was operating in flexible small teams in horizontal governmental structures, where the mentality of peer production prevailed over rigid hierarchy. Moreover, in the participatory Athenian context, social knowledge served as a sorting device: ‘Experienced citizens learned habits of discrimination, of recognizing whom to attend to and whose opinion to trust in what context’ (ibid., 120). Ober identifies two features of Athenian decision-making institutions, which conjoin the innovation-promoting and routinizing aspects of organizational learning: social/knowledge networks and task-specific work teams (ibid., 123). By serving in rotation and being educated in the democratic machine, the Athenian system made experts out of lifelong learning amateurs: ‘Through its day-to-day operations, the Athenian system sought to identify and make effective use of experts in many different knowledge domains’ (ibid., 31). As he puts it,

By participating in ‘working the machine’ of democracy, the individual Athenian was both encouraged to share his own useful knowledge, and given the chance to develop and deepen various shorts of politically relevant expertise ... learning as socialization helped to sustain democracy by granting it ideological legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry. Predictability, standardization, and legitimacy all lowered transaction costs and thereby reduced the friction inherent within every complex system. (ibid., 273)

Cleisthenes is credited with making the most important of the democratic reforms in Athens, significantly enabling the golden era of participatory democracy by creating institutions built for knowledge sharing, lowering communication costs, and context-sensitive information sorting. He did this first of all by creating the weak ties that were crucial to uniting local strong ties across Attica, bridges that were essential to knowledge aggregation. The blatantly artificial tribes in his system drew from three areas, communities located in coastal, inland, and urbanized regions of Athenian territory, whereby a stable local identity was linked to a desired national identity, the participatory citizen of Athens (ibid., 138). According to Ober, the Athenian system intermixed Athenians from different geographic/economic zones in a variety of psychologically powerful activities, such as fighting, sacrificing, eating, and dancing, which led to a strengthened collective identity at the level of the polis (ibid., 142). Athenian citizens acted as individuals bridging holes in the network, linking subnetworks and gaining social capital in the process, similar to the process described in Ron Burt’s (1992) theory on structural holes (ibid., 146). The ability of the Athenian citizen to learn and be part of a knowledge network runs contrary to the ignorant-mob assumption often put forward by historians (Ober, 2010, 162).

In terms of leadership, the Athenian polis did not depend on authoritarian leaders or hierarchy and rejected Spartan-style hypersocialization. Athens relied instead on choices freely made by free citizens to gain its public ends: ‘intermixing the four mechanisms ... for facilitating complex coordination: first choice, informed leader, procedural rules, and credible commitments’ (ibid., 179). For example leadership would shift readily depending on which individuals or groups happened to know something useful, with consensus following from plurality and alignment (ibid., 174). Balancing elite and non-elite preferences meant, for example, that someone like Themistocles in the debates leading to the Athenian decision to fight the Persians at Salamis in 480 BC were able to assume leadership roles by advocating and carrying through innovative policies (ibid., 182). It was indeed his genius in Salamis of using the change of wing direction at a specific time of the day that enabled the small, agile Greek ships to devastate the larger and more inflexible Persian fleet. Lastly, Athenians valued innovation as a good in itself, because it was a manifestation of their communal identity, of what they supposed was special and excellent about themselves as a people – as well as valuing innovation as an instrument (ibid., 275).

A giant leap forward to the 1960s and the birth of the hacker movement, whereby radical geeks argued for free information and open collaborative knowledge networks. The enthusiastic computer virtuosos dreaming of a world where information and knowledge could be produced and accessed by anyone at any time openly and freely, such as Ted Nelson and his Xanadu project of hyperlinked text, and with greater and greater speeds within flows of time and space compression in Gibson’s cyberspace, were no longer dreaming.

The digital revolution saw the term ‘hackers’ used as an umbrella term for any computer intrusion or illegal activity relating to digital networks, from cybercrime (e.g., identity theft, online fraud, ATM attacks) to cyberprotest, (e.g., electronic civil disobedience, symbolic defacements, network disruption) to cyberterrorism (e.g., cyber activities relating to individuals and groups who commit violence against civilians). All these terms and examples are continuously debated, of course, and by no means am I offering here a definitive solution to ideological and ontological preferences. The point is that ‘in the popular press, however, the connotations of “hacker” are most often negative, or at minimum refer to illegal intrusion of computer systems’ (Coleman, 2014).

Broadly speaking, a hacker is involved in an act that is against the rules and involves sophisticated technical knowledge. The literature on hackers has looked at reasons for hacking, such as feelings of addiction, the urge of curiosity, boredom with the educational system, enjoyment of a feeling of power, peer recognition, and political motivations. The more political hackers believe that electronic communications are unsafe, with governments legally tapping data lines, copying electronic mail, and suspecting hacking often enough to get search warrants or confiscate equipment. Taylor and Jordan (2004) argue that overidentification with technical means over political ends and their parasitic relationship to various technological systems means that although they are at the heart of the exercise of power, they remain in an ultimately powerless dependent relationship. This point is reserved for a later discussion about the third phase of digital activism because it relates to WikiLeaks, Anonymous, and other examples.

I am following a long line of scholars who think that the first successful example of digital activism originated from the free/libre open-source software movement (FLOSS) (Wark, 2004; Weber, 2004; Blenkler, 2006). In collaboration with George Michaelides who works in organizational behaviour at Birbeck, we theoretically explored conflict and governance in this movement (Karatzogianni and Michaelides, 2009). In communities that exist at the interface between order and randomness (at the edge of chaos), conflict and crisis can act as a catalyst or a defence mechanism toward establishing governance structures or, failing that, disintegration. Conflict is a catalyst, in the sense of enabling the morphosis of cryptohierarchies, and a defence mechanism, in the sense of forcing communities to separate. Through negotiation and soft control, the community can develop new structures in order to cope with conflict, creating core and periphery groups and cryptohierarchies. In another scenario, due to extreme group polarization, the community is unable to create new structures but branches out and uses conflict as a defence mechanism to avoid centralization. Or, in the worst case scenario, the community separates into two (forking the code), and there is no collaboration between original and fork, in which case the conflict can be constructive or destructive depending on the evolution of the communities and groups involved.

In these communities, conflict and self-organization play a critical role in the emergence of structures: leadership emergence, the bifurcation into core and peripheral groups, and soft control by cryptohierarchies (intracommunal cyberconflict); different levels of group polarization and conflict between communities negotiating their identity, strategy, coordination, and complexity (intercommunal cyberconflict); and lastly, the dynamic relationships between hierarchies and networks. These dynamics are forcing open-source communities and, more often than not, networked communities to exist at the edge of chaos and to constantly engage in lines of flight and resistance from the system of global control while ignoring current capitalist practices and ‘growing their own’ models of self-organizing knowledge creation and exchange (e.g., peer production in open software or hardware communities).

Michel Bauwens (20 October 2007) of the P2P foundation talked of peer-to-peer processes as bottom-up processes whereby agents in a distributed network can freely and voluntarily engage in common pursuits without external coercion, where anyone can access, anyone can use, and any change to the commons belongs to the commons. Peer governance-based leadership on reputational capital is the order of the day: ‘Within the teams, decision making is participative and consensual, and the global coordination is voluntarily accepted and today technically feasible. Small tribes, the victims of civilizational hierarchies, are re-enabled in the new format of affinity-based cyber-collectives’ (ibid.). Postmonetary, postdemocratic, postcapitalist modes of value and exchange, embedded or not in the system, are the answer and solution to the structural crisis of contemporary capitalism (see also Bauwens, 2009).

And yet, very much like ancient Athens (with its exclusion of migrants, foreigners, and women), the open-source and/or free software movement is mistakenly romanticized as the ultimate democratic, egalitarian, and horizontal system of governance:

People often see in the open source software movement the politics that they would like to see – a libertarian reverie, a perfect meritocracy, a utopian gift culture that celebrates an economics of abundance instead of scarcity, a virtual or electronic existence proof of communitarian ideals, a political movement aimed at replacing obsolete nineteenth-century capitalist structures with ‘new relations of production’ more suited to the Information Age. ... It is almost too easy to criticize some of the more lavish claims. ... The hype should be partly forgiven. ... Unlike the shooting star that was Napster, the roots of open source go back to the beginning of modern computing; it is a productive movement ultimately linked to the mainstream economy; and it is developing and growing an increasingly self-conscious identification as a community that specifies its own norms and values. (Weber, 2004, 7)

On the down side, structurelessness is masking power in these communities. The equivalent in open source could be the distribution of knowledge sharing spectacularly skewed (huge gap between core and peripheral developers’ contributions). Is soft control by cryptohierarchies necessary to provide the social glue and facilitate the creation of technical infrastructures and decision-making mechanisms?

Weber argues that open source poses three interesting questions for political economy, which can be summarized as follows: motivation of individuals (why do talented programmers chose to spend time on a project for which they will not be compensated); coordination (‘how does the open source sustain coordinated cooperation among large numbers of contributors, outside the bounds of hierarchical or market mechanisms’); and complexity (‘what is the nature of governance within the open source process that enables this community to manage the implications of Brooks’s Law’ – this is the observation that when manpower is added to a software project, the project falls even further behind – ‘and perform successfully with such complex systems?’) (2004, 11–12). Incorporating Weber’s foci of analysis, the open-source community/ies and the socioeconomic and politico-economic cyberconflicts (Karatzogianni, 2006) that arise can be described firstly as ultracreative, intracommunal conflicts between individuals in an open-source community. This can lead to much more diverse knowledge creation, or, in the worst case scenario, code forking. Forking, were the code is replicated and continued by another team of developers is different from code branching. What is interesting in intracommunal conflicts are issues of personal freedom, the right to fork, ownership, leadership direction, competitive technical visions/ideologies, reputational risk of the original project, and fork leader recruitment. For the purpose of this discussion, it is also interesting for intracommunal conflicts to explore group polarization, cryptohierarchies, and what Weber terms the ‘winner-takes-all dynamic within certain kinds of open source projects’ (2004, 160).

Secondly, intercommunal conflicts, between different open-source communities, raise questions of coordination (too much and too little), complexity (how much the community can handle), and ideology (different political visions for the open source, expressing all inclinations, from anarcho-syndicalism to libertarianism and even to right-wing ideologies, with free software emphasizing the freedom aspect and the Open Source Initiative establishing links with business). In the bigger picture, there is a general conflict between the open-source community and aligned proprietary software companies supporting open-source initiatives against the Microsoft monopoly and other proprietary players. Here macro-organizational structures and the dynamics of the IT industry are important, as well as questions of identity, strategy (framing), and structure (hierarchy vs network or hybrid, such as the Linux case, when Torvalds started rerouting submissions to lieutenants). Within this bigger picture, a metaconflict occurs synchronously, bringing all these different levels together and posing them in direct and intense contact and contrast to the current global system of capitalist accumulation.

The edge of chaos is defined as a state of a system where the system undergoes a phase transition; that is, its behaviour shifts from one state to another. In social systems, the edge of chaos refers to the conceptual region between order and chaos. It refers to a system being at a ‘self-organized’ state. In open-source communities, and possibly other network structures, the edge of chaos is captured in two ways in which the system can self-organize. First, open-source communities exhibit a power law distribution (e.g., Healy and Schussman, 29 January 2003; Madey, Freeh, and Tyran, 2005). The power law distribution in the Internet literature comes up in the study of links on the Internet, and as Benkler points out, ‘if a tiny minority of sites gets a large number of links, then the vast majority gets few or no links, it will be very difficult to be seen unless you are on the highly visible site’. Not only that, but the emergent new hierarchy is becoming ‘a more intractable challenge to the claim that the networked information economy will democratize the public sphere’ (Benkler, 2006, 241–242). Every successful community tends to be organized into a two-tier structure with a core and a periphery group (Michaelides, 2006). The significance of these two forms of self-organization in this discussion is that this is not only unavoidable, but also a necessary component to the success of the community. First, networks that follow power law distributions tend to be more robust and are more adaptable to environmental disturbances (e.g., Barabási, 2002). Second, the fact that communities tend to separate into core and periphery enables them to effectively exploit and integrate knowledge from diverse sources (Michaelides, 2006). Issues of leadership and soft control are equally relevant to the different types of conflict occurring on the intracommunal, intercommunal, and metaconflict levels, when conflict becomes a catalyst for self-organization, or a defence mechanism against the emergence of cryptohierarchies or explicit hierarchies in the form of core and periphery.

Group polarization occurs when ‘members of a deliberating group move toward a more extreme point in whatever direction is indicated by the members’ predeliberation tendency’ (Sunstein, 1999). Online communities tend to be more polarized, while the bazaar empowers louder and more aggressive individuals (Raymond, 1998), often exacerbating online conflicts, leaving out people who disagree, while empowering people with a common cause, and the opinion of the mediocrity gets adopted, having reached a critical mass. This is directly linked to social cascades and cryptohierarchies both informational and reputational. Familiar and long-debated issues do not depolarize easily (so in Open Source Software (OSS) political/ideological issues do not depolarize easily, but technical issues do). Polarization increases when the group defines itself by contrast to another group; when there is some sense of identity (reinforcing group cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Four Phases of Digital Activism and Cyberconflict

- 1 Origins and Rise of Digital Activism (19942007)

- 2 The Third Phase (20072010): Spread of Digital Activism

- 3 The Fourth Phase (20102014): Digital Activism Invades Mainstream Politics

- 4 The Future of Digital Activism and Its Study

- Bibliography

- Index