- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The rise of multinational corporations (MNCs) from emerging markets has been a major development during the last decade. An important feature of emerging market MNCs is their close relationship with home states. The book investigates this special kind of relationship and explores how it affects the cross-border activities of these corporations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Multinational Corporations from Emerging Markets by A. Nölke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Business internazionale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

General Perspectives

1

(Multi?)national Corporations and the State in Established Economies

John Mikler

1.1 Introduction

It is often claimed that corporations are increasingly multinational, and that they are therefore freed from the territorial ‘shackles’ of national governments. That liberal capitalism is writ large upon the global stage, with multinational corporations (MNCs) in the lead roles and states performing the supporting ones, was celebrated by the likes of Fukuyama (1992) with his much cited, although now modified, prediction of the ‘end of history’ with the end of the Cold War. There was the Washington Consensus of the 1980s and 1990s, through which the Bretton Woods institutions imposed such a neoliberal vision on developing countries. This is said to have since given way to a post-Washington Consensus, which is liberal rather than neoliberal – it is more a matter of principles to be made policies by states, rather than an inevitable ‘blueprint’ of measures to be adopted (see e.g., Headey, 2009). As such, a global vision, as opposed to an inevitable ‘reality’, is now more the case, but it is global nonetheless.

However, rather than taking a global perspective, this chapter focuses on corporate-state relations in distinct national, and to some extent regional, contexts in order to demonstrate the endurance of diversity between states with advanced, industrialized economies. This is because global capitalism is in many respects not as global as often claimed by those who stress the economic aspects of globalization.1 MNCs’ operations and locations remain more territorially defined than is often acknowledged, and in particular their home bases remain of great importance to them: many remain embedded in well-established economies where distinct national structures of governance have become institutionalized over time. While other chapters in this book analyze the way in which those MNCs that are emerging from the rapidly growing economies of Brazil, Russia, India, and China (the BRICs) are similarly embedding themselves in their home states, the central point made in this one is that the incumbent states and their MNCs are bound by the institutional structures they have created and in which they have become deeply embedded economically, socially, and politically over time.

In the first section, the territorially grounded nature of MNCs is considered. Contrary to the notion of the placeless, transnational corporation, the locations of the world’s largest corporations are shown to be analogous to a map of world power – such corporations come from the world’s dominant, established industrialized states. It is therefore the case that as market economies rise, so too in a similar fashion do their corporations. The two are inseparable. In the second section, the nature of this relationship is considered, particularly variations from more liberal to more state-coordinated varieties of capitalism, and in this respect the point is made that states lie on a spectrum from ‘arms-length’ liberal to integrated coordinated relations with their corporations. In the third section, it is demonstrated that these relations evolve over time, with the potential for this evolution both enabled and constrained depending on the path dependence of existing institutions. The implications for established market economies are that rather than convergence on a single variety of capitalism, or a single form of corporate-state relations, diversity is likely to persist on a national and regional basis even as the global economy becomes more interconnected. Similarly, the implications for emerging market economies are that their governments and MNCs potentially have considerable ‘room to move’ as they develop new institutions of governance in the process of emerging, just as the established economies did before them. The room they have – both the extent of it and what they have done with it – is the subject of the chapters to follow in this volume.

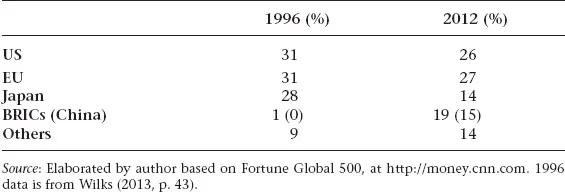

1.2 Reterritorializing multinational corporations

Corporations are increasingly multinational. However, this does not mean that a deterritorialized, or ‘global’, view of them is appropriate. While their economic interests and their operations increasingly transcend national boundaries, nevertheless they are based in some states and some regions from which they emerge to impact on others. Chang (2008, p. 32; see also Fuchs, 2007; Harrod, 2006) notes that the wealthy, industrialized countries account for 70 percent of international trade and make 70–90 percent of global foreign direct investment (FDI). But more accurately, it is their corporations that do so. The FT Global 500 companies2 are responsible for 70 percent of international trade and at least 80 percent of the world’s stock of FDI (Rugman, 2000; Bryant and Bailey, 1997). The rather close correlation between the figures for rich, industrialized states’ trade and FDI and those of these corporations is no accident. Their nationality – that is, where they are based – is like a map of global economic power. As this map of power has shifted, so too has their nationality. Table 1.1 demonstrates that as the emerging market economies of the BRICs have grown in global economic importance, so too have their corporations. Of the corporations in the Fortune Global 500,3 the majority remain headquartered in the United States (US), the European Union (EU), and Japan. However, today they are also increasingly headquartered elsewhere, with new Chinese MNCs in particular now making up 15 percent of the world’s largest corporations. As the center of the world economy has moved from the transatlantic closer to the Asian sphere, so has the location of the world’s largest corporations. In fact, 36 percent of the Fortune Global 500 companies are now located in the Asian region.4

Table 1.1 The nationality of corporations in the Fortune Global 500

The implications of this go beyond merely their location, also raising questions as to their control. In particular, it has often been noted that national trade and investment figures are actually those of the corporations that produce them. By the 1990s, 60–70 percent of trade in manufactured goods between Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries was intrafirm, rather than interstate (Bonturi and Fukasaku, 1993; see also Bardhan and Jaffee, 2005) – that is, the supply chains of the world’s largest corporations are what produce the national figures. Rather than the data reflecting trade and investment on the basis of national comparative advantage, they reflect the corporate strategies of the world’s largest corporations, headquartered in the world’s largest economies. One response to this would be to say that these corporations are market actors being driven by market imperatives. As the market for goods and services is increasingly global, so are they, and they shift their operations accordingly. However, there are (at least) two points to make in respect of this.

First, casting MNCs in this manner ‘underdraws’ them as mechanisms of profit maximization, suggesting that they are purely the servants of market forces and market imperatives. Of course, they have to be profitable and successful in the markets for their goods and services, but I have previously argued that seeing corporations as ‘market actors’, and indeed ‘the market’ as a concept for understanding global economic relations, makes assumptions about the global economy that should be more widely challenged (Mikler, 2013, 2012). In particular, the reality is that the global economy is highly concentrated and oligopolistic. All of the world’s major industrialized sectors are now controlled by five MNCs at most, and 28 percent have one corporation accounting for more than 40 percent of global sales (Harrod, 2006, p. 25; see also Fuchs, 2007). The world’s largest MNCs, based in the world’s largest economies, control trade and investment flows and do so because they control the markets for their products. They do not respond to market forces. They make them.

It is also the case that in making and controlling these markets, they do so from the states in which they are headquartered. Although they have global interests, their operations are much more territorially grounded than is often held to be the case. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s transnationality index (TNI) is a simple composite average of foreign assets, sales and employment to total assets, sales, and employment. Although 82 of the world’s 100 largest corporations ranked by foreign assets have a TNI of over 50, and the average TNI of a corporation in this list is 63,5 suggesting a high degree of independence from their home base, there are dangers in making generalizations. For example, the average TNIs of US, German, and Japanese firms in the top 100 MNCs are just 51, 55, and 52 respectively. On average, these well-established MNCs from the world’s most well-established industrialized states retain half their sales, assets, and employment at home, although they have had the most time to ‘go global’ (UNCTAD, 2011a).

Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that there will be a future trend to a greater decoupling of these MNCs from their home states. Many of the seemingly most global MNCs are in fact more regional than global. There is a body of scholarship by Rugman with various co-authors (Rugman, 2005; Rugman et al., 2007; Rugman and Girod, 2003; Rugman and Collinson, 2004) that demonstrates that a very significant proportion of the Fortune Global 500 firms’ assets and operations are located in their home region. As such, they use their headquarters in their home state as a base from which to control and dominate their region(s). Relatedly, some MNCs are more accurately seen as binational. For example, Voss (2013) notes that MNCs based in Taiwan and Hong Kong have very high TNIs simply because they locate factories in mainland China, but their headquarters remain at ‘home’. As the opportunities for efficiencies/exploitation shrink with the rise of the BRICs and other emerging market economies, and as the cost of oil and carbon emissions ultimately must be factored into corporate strategic decision-making, enhanced national and regional, rather than global, strategies may become increasingly attractive to MNCs and an incentive for them to rationalize their supply chains (see, e.g., The Economist, 2011).

Clearly, the notion of the placeless MNC does not stand up to scrutiny. The reality is that all markets are highly oligopolistic, and therefore power is concentrated in the hands of a small number of corporations that dominate their industry sectors, and they are based in the world’s dominant countries and regions. The relationships they have with their home state governments are therefore crucial. How they are institutionally embedded in their home states is considered in the following section, as well as the relationships they have with the governments of states in which they invest.

1.3 Varieties of capitalism, varieties of state-corporate relations

At the height of initial debates in the post-Cold War 1990s about what was then starting to be called globalization, the inevitability of an integrated global economy was seen as producing a tendency toward a neoliberal form of the state. Authors such as Fukuyama (1992), whose declaration that liberal capitalism writ large upon the world had delivered ‘the end of history’ were made as nothing less than a ‘primeval scream of joy’, as Bhagwati (2004, p. 13) colorfully put it, by someone standing astride the ‘corpse’ of the now-missing alternatives to the neoliberal policies of the Washington Consensus: minimal government in both size and scope; borders opened to trade and financial movements; national deregulation to let the market work; and the privatization and marketization of the provision of goods and services.

However, as these policies were imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions on developing countries in the form of loan conditions in the 1990s, it appeared that markets were the masters of governments not just because of a lack of alternatives, but actually by design. It was not so much the case that globalization meant that inevitably ‘your economy grows and your politics shrinks’ (Friedman, 2000, p. 105), resulting in Washington Consensus-style policies via convergence on a liberal and ultimately neoliberal form of the state. Instead, this policy ‘choice’ was imposed on countries that were comparatively less able to resist it. Indeed, those doing the imposing of the policies did not adhere to them themselves. In 2000, government expenditure in the world’s major advanced economies (the G7) was 42 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on average. By 2010, it had grown to 47 percent. This may be contrasted with the 25 to 30 percent average for Latin American, Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan African states (IMF, 2011). The consensus on the part of elites in the established economies still exists, even in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (according to Wade, 2010), but it does not seem to have produced a shrinking state in terms of size.

It also has not produced homogeneity in the role of the state. In reality, globalization remains very much ‘what states make of it’ (Clark, 1999, p. 55), although more accurately it is what powerful states make of it (see Drezner, 2007). A good starting point for understanding this is the consideration that the TNI of corporations may be seen to be related to the TNI of states. Similarly to the TNI of corporations, this measures the degree to which states’ economies are internationalized, based on the average of the four indicators of FDI flows as a percentage of fixed capital formation; FDI inward stocks as a percentage of GDP; stock; foreign affiliate value added as a percentage of GDP; and employment by foreign affiliates as a percentage of total employment. It is only the smallest countries that have high TNIs. The highest are Belgium, Singapore, and Luxembourg with TNIs of 66, 65, and 65 respectively (UNCTAD, 2008). It is also the case that because they have very small domestic markets, the MNCs emanating from them also have very high TNIs. By comparison, not only do the MNCs from Germany, the US, and Japan have lower TNIs, but despite their huge role in the global economy, these states themselves have TNIs of just 11, 7, and 2 respectively. This is important because as Wilks (2013, p. 38) notes, ‘indices of country economic transnationality are potentially also indicators of national influence within global governance’. Those states whose economies are more penetrated by corporations of other nationalities, are likely to find themselves pressured to conform to ‘modes of behavior, styles of regulation and form(s) of political activism’ (Wilks, 2013, p. 38) with which these corporations are familiar ‘at home’. Putting it simply, states with a high TNI are more impacted by corporations from other states, while those with a low TNI’s corporations do the impacting.

The manner in which this occurs is of course not straightforward. On the one hand, because MNCs’ operations cross borders, they may be viewed as a bundle of organizational capabilities, one of which is their ability and flexibility to absorb and gain new knowledge in any context (e.g., Kogut, 2005). From this it follows that the learning ability of MNCs, and therefore their abilities to adapt and change in different national contexts, is crucial to their international performance. As they are international organizations as well as nationally and regionally embedded ones, they therefore can change and adapt according to their circumstances – thus they ‘translate the relationship of globalization and regionalization into an organizational challenge’ (Heidenreich, 2012, p. 557). However, a crucial point to make in this respect is that, as Whitley (2009) finds, because they are shaped by their national business systems, where possible they choose not to do so. Critics of globalization may find Wolf’s (2004, p. 191) statement that ‘multinational corporations would not dare operate plants in very different ways in different countries’ odd, to put it mildly. Yet, in institutional terms, the statement rings true because in addition to being internationally active, as per the above discussion, MNCs should be seen as still very much nationally and regionally embedded organizations. As Heidenreich (2012, p. 567), puts it, ‘the national embeddedness of companies contributes to the reduction of uncertainties and to the solution of organizational coordination problems’, and as such there is little incentive for MNCs to ‘fix’ what they may not regard as ‘broken’.

It follows that even if they have the capacity for adaptation, studies such as Kahancová (2007) show that rather than doing so unopposed in different national contexts, corporate organizational inertia means routines that have supported growth and legitimacy in an MNC’s home country tend to be retained where possible. Having ‘solved’ their coordination problems, which shape the relationships they have with their employees, industry associations, unions, educational institutions, competitors, shareholders, banks, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders, why would they be eager to change these arrangements unless forced to do so? Rather than some disembodied, tra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Toward State Capitalism 3.0

- Part I General Perspectives

- Part II Country Studies

- Part III International Institutions

- Conclusion: State Support for Emerging Market Multinationals

- Bibliography

- Index