eBook - ePub

Gendering Family Policies in Post-Communist Europe

A Historical-Institutional Analysis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Through the use of a historical-institutional perspective and with particular reference to the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia; this study explores the state of family policies in Post-Communist Europe. It analyzes how these policies have developed and examines their impact on gender relations for the countries mentioned.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gendering Family Policies in Post-Communist Europe by S. Saxonberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

In 1872, the Austro-Hungarian Empire passed a law codifying the division of childcare facilities into nurseries for children under three, and kindergartens for children 3–5. Approximately 80 years later, in the early 1950s, the communist regimes in Central Europe decided to move nurseries to the Ministry of Health. At the time, few would have expected these decisions to have a long-lasting influence on gender relations in the region; yet that is exactly what happened. Consequently, the saga of post-communist family policy begins in the 1870s. It is a saga in which historical-institutional developments have influenced policymaking to such an extent that, despite the attempts of the Soviet Union under Stalin to force a unitary model on the Soviet-bloc countries, the Central European states developed rather different policies based on their distinctive histories. Indeed, not only did these countries take different approaches to family policy under communist rule; the basic differences continue to this day. This book focuses on four countries with a communist past (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia), and compares them with three West European countries (Germany, Sweden and the UK), in order to explain how it is possible for such policies to develop so differently in Central Europe, and to remain so different after the collapse of communism. It follows the countries up until the year 2010, after which I finished my fieldwork and began writing this book.

The focus: family policy

If one is interested in post-communist gender relations and the issue of how the Marxist-Leninist experiment in Europe has influenced gender relations, then family policies are a good place to start. As many feminist scholars have emphasized, few policies have as much influence on gender relations as family policies. If family policies encourage women to stay at home for long periods of time to take care of children, while encouraging men to remain in the labor force, then women will not be able to achieve equality with men. On the other hand, if family policies encourage men to share in the double burden of domestic and paid work, then traditional gender roles may become weaker. As long as women do most of the household work, they will not be able to compete equally with men in the public sphere, such as politics and the labor market.

Consequently, although the discourse on social policy had traditionally focused on labor-market policies, feminist scholars began emphasizing the importance of family policies after Helga Hernes (1987) claimed that the Scandinavian countries were developing “women friendly welfare states” (e.g., Lewis 1993; Sainsbury 1994; Lewis 1997). As Jane Jenson (1997: 184) writes: “If … we change our lens and claim that welfare programs are primarily about care, then unemployment insurance is no longer the flagship program of the welfare state.” Tamara Hervey and Jo Shaw (1998: 44) assert: “Many would argue that the key to citizenship is independence, and that the key to independence is employment, leading to questions about responsibilities (private and public) for childcare and other dependent relatives. Hence care-giving and the labour market should never be separated.” Thus, according to a common view, family policy affects gender relations as much as it affects female labor-market participation, and family policy is at least as important for women as pure labor-market policy.

Family policy is not just important for gender relations, it is also important for the rights of children. In the Swedish discourse, for example, policymakers now emphasize that children too have rights: the right to spend time with their fathers. Thus, a report from the previous social democratic government proclaimed: “The child has a right to early and close contact with both parents” (Batljan et al. 2004: 17).1 Similarly, a report from the current center-right government suggests that “an increase in equality can contribute to more secure family relations for children as well as creating more equal opportunities for women and men to have careers” (Swedish Ministry of Social Affairs 2007: 7).

This study concentrates on whether social policies give women incentives to work or to stay at home, and whether they give fathers incentives to share in childraising tasks, because these policies have the greatest impact in terms of promoting or discouraging gender equality. Social policy can be degenderizing, in the sense of aiming to eliminate gender roles.2 If no correlation exists anymore within a country between gender and the amount of formal work (in the labor market) and informal work (in the home) that one does, then that society has come a long way toward removing pre-determined gender roles. By contrast, policies that openly support separate gender roles by inducing women to stay out of the labor market are explicitly genderizing. Laissez-faire policies offer yet another variant: they are implicitly genderizing. Given the patriarchal starting point, if the government does not intervene in the market – for example, by subsidizing daycare and encouraging fathers to share in the leave time – then many families will not be able to afford childcare on the market, and mothers will be likely to do all the childcaring. Given the fact that fathers in most families have higher incomes than mothers, families are likely to conclude that they cannot “afford” the loss of income, even if the father wants to stay at home for a period with the children. Cultural patterns are also important, for as long as no father quotas exist (which reserve a portion of the leave for fathers only), fathers will face pressures from their employers and work colleagues to remain at work. Men who want to take parental leave go against the expectations of their employers and colleagues (who will conclude that they are not “ambitious”), while mothers who spend time at home with their children are merely doing what their colleagues and employers expect them to do (cf. Haas et al. 2002).

Space does not allow for a detailed discussion of why I prefer a typology based on degrees of genderization and degenderization to more common typologies – such as the most common one, which is based on degrees of familialization and defamilialization. I explain this in detail elsewhere (Saxonberg 2013); basically, however, I see the following advantages with the terms “genderization” and “degenderization.” First, they are much clearer than familialization and defamilialization: they explicitly indicate that the goal of mainstream feminists in the area of social policy has been to eliminate gender roles. Defamilialization is a more ambiguous concept. Supporters of the term framed it originally in terms of increasing the financial autonomy of women (Lister 1994; Orloff 1996), but scholars commonly use it in the manner implied by the name: to indicate the degree to which responsibility for childcaring is taken away from the family. This leads to problems in how to characterize parental-leave programs that encourage fathers to share in the leave time. While this increases gender equality and should be something that feminists support, it is not clear whether such policies are familializing (because they encourage family members to take care of the children) or defamilializing (because they increase the financial autonomy of women). As a result, scholars use the terms differently in their studies and often come to sharply contrasting results. A second problem is that the terms “familializing” and “defamilializing” are only applicable to care policies, whereas the terms “genderizing” and “degenderizing” are applicable to all types of social policy. Thus, the latter terms offer a unitary framework for analyzing all types of social policy, and we do not have to create new typologies for each type of policy.

Because of this focus, certain issues are left out of the current study, although they are clearly important for understanding the general condition of women. Abortion is one obvious example. The abortion issue is central for women, because it concerns their right to control their own bodies. However, it does not influence the decision of women to work or stay at home once they have children. Finally, it should be noted that, when I refer to the Central European countries as having been “communist-ruled,” I mean this only in the neutral sense that parties which considered themselves to be communist were in power (although they did not always use the word “communist” in their name); it is not to imply that these regimes came anywhere near Marx’s vision of a classless society, wherein the state “withers away.”

The special situation of post-communist countries in Central Europe

When the communist regimes lost power, Central European women found themselves in a historically unique situation. On the one hand, they enjoyed the highest employment levels in the entire world (which were the result of degenderizing policies), with only the Scandinavian social democratic countries coming close. On the other hand, in contrast to the case in the Scandinavian countries, little discussion arose about the need for men to share in household and child-raising chores. As a result, the household remained strictly the domain of women (e.g., Gucwa-Leśny 1995: 128). Thus, parental-leave policies were extremely genderizing, as they only allowed women to stay at home with their children. Under such conditions, the “double burden” of paid and unpaid work became particularly heavy.

Despite these important similarities, the communist-ruled countries displayed important differences; and these differences have basically continued after the fall of the communist regimes. In fact, a closer look at the development of post-communist countries brings up the question of lack of development. The really striking question is why policies after the fall of the communist regimes have changed so little. From the perspective of path dependency, it is interesting to note that 1989 did not constitute a critical juncture. Thus, the main research question becomes: why do the countries of Central Europe differ so greatly in the area of family policy today, notwithstanding their shared experience of Stalinism? Indeed, family policies already differed under communist rule, which leads to the additional question of how such differences could arise, given that the countries in question all belonged to the Soviet bloc and were under great pressure from the Soviet Union to pursue certain policies.

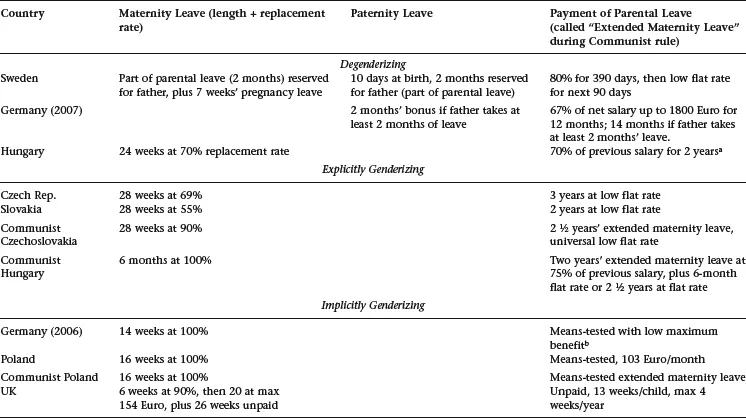

The communist-ruled countries followed the more “continental” (and genderizing) European model of parental leave, in that they allowed women to stay at home for several years, while only paying generously for an initial maternity leave of about half a year. Although maternity leave was generous in all Central European countries – paying 90–100 percent of mothers’ previous income – they were more residual and implicitly genderizing in Poland than in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, because in Poland they were limited to four months compared to six months in the other countries (see Table 1.1). In contrast, the more generous 6-month maternity that the communist regimes introduced in Czechoslovakia and Hungary was more explicitly genderizing, since it explicitly induced mothers to leave the labor market for longer periods of time.

Furthermore, each country introduced a different type of “extended maternity leave” following the initial maternity leave. That is, in addition to having instituted a system of maternity leave based on the income-replacement principle, all of the countries introduced an extended maternity leave that allowed mothers to stay at home until their children reached the age of three. However, the different systems were based on different principles in the different countries. They did have in common that – with a slight exception in Hungary in the 1980s – they were only open to mothers; thus, they were known as “extended maternity leave” rather than as parental leave. Now that the leave is open to fathers as well, it is officially called parental leave. Again, Poland introduced a more liberal, implicitly genderizing variant than the other countries. At first it included no monetary benefits with the extended leave; then, in 1981, it did introduce monetary benefits, but only on a means-tested basis. Meanwhile, Czechoslovakia followed the more conservative, explicitly genderizing option of providing an extended leave with a low flat-rate monetary benefit. Hungary borrowed elements of the Nordic social democratic model by eventually introducing an earnings-related extended leave that paid 75 percent of the mother’s previous income until the child reached the age of two. Unlike the social democratic Scandinavian countries, however, Hungary did not make this leave available to fathers; therefore, it was still explicitly genderizing. Hungary also had an explicitly genderizing flat-rate alternative which mothers could use until their children reached the age of three.

Table 1.1 Parental-leave arrangements

a But with a relatively low ceiling of twice the minimum wage

b 450 Euro during 12 first months or 300 Euro for 24 months

Sources: OECD (2007a). For the recent German reforms: http://www.bundesregierung.de/nn_66124/Content/DE/StatischeSeiten/Breg/Reformprojekte/familienpolitik-2006-08-21-elterngeld-1.html; for Hungary under Communist rule: Haney (2002: 178); for Poland and Czechoslovakia: Saxonberg and Szelewa (2007).

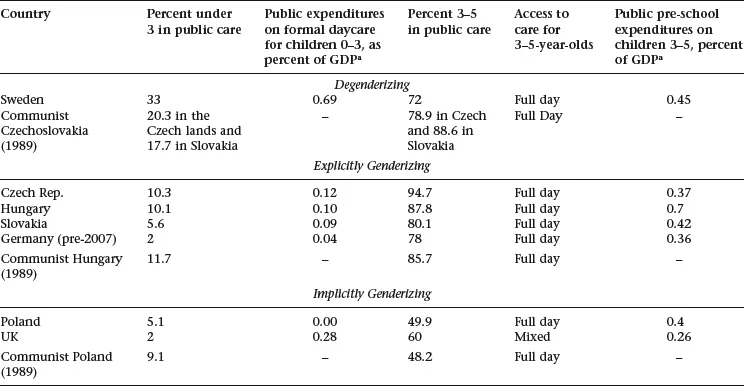

Where childcare facilities were concerned, the communist regimes initially pursued degenderizing policies by investing in rapid expansion. Eventually, the vast majority of children aged 3–6 attended kindergartens in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Poland remained more laissez-faire and implicitly genderizing, as it only allocated enough kindergarten places for about half the children (see Table 1.2). Similarly, although all three countries expanded access to nurseries for children under three, Poland also remained a laggard in this area. In the 1950s and 1960s, when the expansion of daycare places was most rapid, the Central European communist countries were among the world leaders in this field. However, the percentage of children under three attending formal daycare never got much above 20 percent (and then only in Czechoslovakia); thus, the level of childcare support was rather modest compared to today’s levels in Western Europe. Czechoslovakia, then, had a relatively degenderizing model in the area of childcare, giving it a hybrid system of explicitly genderizing parental leave and degenderizing childcare policy. Hungary’s measures were explicitly genderizing in both areas, and Poland’s were implicitly genderizing in both areas.

Contrary to expectations that a radical break would occur, these patterns basically continued after the fall of the communist regimes, except in the case of childcare for children under three. Poland radically cut back support for nurseries serving children under three, while the Czech and Slovak republics both did the same after the break-up of Czechoslovakia. Hungary, however, was an exception, as the percentage of children attending nurseries in that country declined by only a few percentage points. The other big change is that extended maternity leave has been transformed into parental leave which in theory is open to men, even though policymakers in these countries do not expect men to actually go on leave. As under communist rule, then, these countries exhibit important differences. Poland has a more laissez-faire, implicitly genderizing policy with means-tested parental leave and a lower level of support for daycare than the other countries. The Czech and Slovak republics, meanwhile, have more conservative, explicitly genderizing policies, with flat-rate parental leave and virtually no support for nurseries, but much greater support than Poland for children aged 3–6 to attend kindergartens. Nevertheless, because support for daycare facilities for children under three has radically decreased, Czech and Slovak childcare policies are no longer degenderizing; instead, they have become explicitly genderizing. Hungary, finally, retains a more Scandinavian type of earnings-related parental leave (although the support level has fallen from 75 percent to 70 percent of previous income); however, since the leave is now open for men it has become relatively degenderizing. It is also open to grandparents when the child is at least one year old (Őri and Spéder 2012). However, in contrast to the governments of the Nordic countries, which introduced parental leave based on income replacement in order to encourage men to take a larger share of the parental leave time, Hungarian governments have not openly encouraged men to go on parental leave. Nor have they seriously contemplated introducing “daddy months” as in Iceland, Norway and Sweden. The supplementary flat-rate leave that Hungarian parents can take until their children reach the age of three still remains in place. Hungary also continues to provide much greater support for kindergartens than Poland; and, in contrast to the other countries, it has succeeded in keeping most nurseries open. So the question still remains: why do these policies differ so much among the countries in question, and why have they changed so little since the fall of the communist regimes?

Table 1.2 Public support for childcare facilities

a average for 2003/2005

Sources: Pettit and Hook (2005: 790); Meyers and Gornick (2003); Saxonberg and Sirovátka (2006). Figures for Portugal and Spain from Rydell (2002); for Spain 3–6 from The Clearinghouse on International Developments in Child, Youth and Family Policies at Columbia University. Statistics on spending for daycare from www.oecd.org/els/social/familv/database. Statistics on children attending kindergartens in Austria from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/55/55/38969007.xls.

Statistics on proportion of children 3–5 attending pre-school on part-time basis from EU-SILC 2006 provisional in EGGE (2009: 78).

Common explanations

This book presents one of the first comparative historical-institutional explanations of post-communist family policies. The typical alternative hypotheses, such as those citing the economic situation, political parties, the role of international organizations, or the mobilization of women are not able to explain the differences in family policies among the Central European countries, even if they do help to explain the details of policy development and adjustment. Until very recently, very few studies have looked at differences in post-commun...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Transition in Central Europe Revisited

- 3 Historical-Institutional Development

- 4 The Influence of International Organizations

- 5 Institutional Framework

- 6 Attitudes of the Population

- 7 Strategies and Political Opportunities for Women’s Organizations

- 8 Political Parties and Policymakers

- 9 Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index