eBook - ePub

Luigi Einaudi: Selected Political Essays

Volume III

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Luigi Einaudi: Selected Political Essays

Volume III

About this book

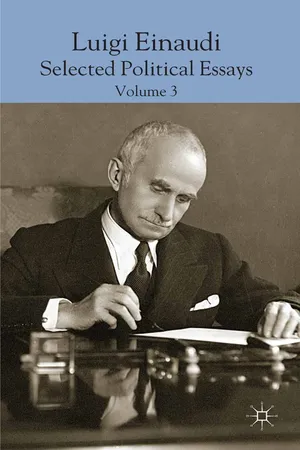

Luigi Einaudi (1874-1961) was a leading liberal Italian economist, economic historian and political figure: Governor of the Bank of Italy, Minister for the Budget and President of the Italian Republic. He was a prolific writer in all fields and his writings testify to his outstanding contribution to economics during his long career.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Luigi Einaudi: Selected Political Essays by Kenneth A. Loparo, C. Malandrino, V. Zanone, Kenneth A. Loparo,C. Malandrino,V. Zanone,Domenico da Empoli,Domenico Da Empoli,Corrado Malandrino,Valerio Zanone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Ideas and Ideals

1

Preface to Italian Edition of On Liberty by J. S. Mill*

In times of mortification of the spirit, when, to sap the rebels’ voices, the dominators proclaim the unanimity of internal consensus, affirming commonality of ideas to be necessary in order for the homeland to flourish and be respected by the foreigner, it is worth re-reading the great books on freedom. I open the Areopagitica and read the following words that John Milton wrote in 1644:

when a city shall be as it were besieged and blocked about, her navigable river infested, inroads and incursions round, defiance and battle oft rumoured to be marching up, even to her walls and suburb trenches, that then the people, or the greater part, more than at other times, wholly taken up with the study of highest and most important matters to be reformed, should be disputing, reasoning, reading, inventing, discoursing, even to a rarity and admiration, things not before discoursed or written of, argues first a singular good will, contentedness, and confidence in your prudent foresight, and safe government, lords and commons; and from thence derives itself to a gallant bravery and well-grounded contempt of their enemies, as if there were no small number of as great spirits among us, as his was who, when Rome was nigh besieged by Hannibal, being in the city, bought that piece of ground at no cheap rate whereon Hannibal himself encamped his own regiment. Next, it is a lively and cheerful presage of our happy success and victory. For as in a body when the blood is fresh, the spirits pure and vigorous, not only to vital, but to rational faculties, and those in the acutest and the pertest operations of wit and subtlety, it argues in what good plight and constitution the body is; so when the cheerfulness of the people is so sprightly up, as that it has not only wherewith to guard well its own freedom and safety, but to spare, and to bestow upon the solidest and sublimest points of controversy and new invention, it betokens us not degenerated, nor drooping to a fatal decay, but casting off the old and wrinkled skin of corruption to outlive these pangs, and wax young again, entering the glorious ways of truth and prosperous virtue, destined to become great and honourable in these latter ages.

The poet of Paradise Lost continued:

Methinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks: methinks I see her as an eagle renewing her mighty youth and kindling her undazzled eyes at the full midday beam; purging and unscaling her long-abused sight at the fountain itself of heavenly radiance; while the whole noise of timorous and flocking birds, with those also that love the twilight, flutter about, amazed at what she means, and in their envious gabble would prognosticate a year of sects and schisms.

The short book on Freedom by John Stuart Mill is now being republished in an Italian version at a moment when the right to criticism, the right to eschew conformity and the arguments underpinning the struggle against uniformity urgently need to reassert themselves. As the author observes in his Autobiography, the essay on freedom, which was composed after prolonged meditation, and in which almost every sentence was, with the advice of his wife, written and rewritten several times from 1854 onwards before its publication in 1869, is almost the textbook of a fundamental truth: it is of supreme importance, for man and society, that there be a great variety of types and characters and that human nature should have full freedom to expand in innumerable and contrasting directions. For if, as Mill points out, a particular doctrine gathers around itself the majority of citizens and organizes social institutions and human action in its own image, then the new generations will be educated to the new creed, which will little by little acquire the very same force of compression as was long exerted earlier by the beliefs the new doctrine has now supplanted.

Fascism, in some respects, is the result of the weariness that arose in the spirit of Italians after the protracted and furious internal conflicts of the post-war period; it is an attempt at regimenting the nation into allegiance to a single flag. Men’s spirits, yearning for peace, calm, rest, quietened upon hearing the word of one who promised these blessings. But heaven forfend if the natural aspiration to be free from civil war, from that brutal degeneration of political struggle in Italy between 1919 and 1921, were to turn without any dissent whatsoever into absolute conformism to the nationalistic gospel imposed by fascism! This would be the death of the nation. With the abolition of freedom of the press, with restriction on freedom of thought, with the denial of freedom of movement and labour as a result of the prohibitions and monopolies exercised by the corporations, the country is being thrust back towards intolerance and uniformity. An attempt is under way to forcibly impose the unanimity of consensus and ideas because, it is argued, truth must be defended against error, good against evil, the nation against the anti-nation.

As a counterargument to these mortifying propositions, which Milton himself had held to be harmful in the extreme, the essay by Mill expounds the logical justification of the right to dissent and offers a demonstration of the social and spiritual utility of the struggle. It is necessary to reread Mill’s demonstration of the following immortal principles:

First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility.

Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied.

Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on man’s character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience.

A litany of errors, conformism, concord and reactionary laws on abuses committed by the press are synonyms and evidence of civil decadence. Struggle on behalf of different ideas, criticism, rejection of conformism, freedom of the press – all these are the harbinger of eras distinguished by the ascent of peoples and states. The years of forced consensus from which we are striving arduously to break free have led Italians towards renewed appreciation of the right to discord and the advantages thereof. Italians realize that freedom is not a mere tool but a shared goal whose achievement is crucial for the other civil, political and spiritual goals of life. But, perhaps, this is more truly a sentiment than a profound conviction. It is fitting, therefore, that Mill’s essay, which our forefathers held in the highest admiration, can thus once more be contemplated by Italians as we pursue the ardent quest for the foundation and the limits of the idea of freedom.

__________________________

* First published in John Stuart Mill, La libertà, with a preface by Luigi Einaudi, Torino: Piero Gobetti editore, 1925.

2

New Liberalism*

The widespread talk of ‘new’ liberalism quite spontaneously prompts the sceptic to ask what distinguishes ‘new’ liberalism from the ‘old’ version. The answer is obvious: there exists no substantial difference, no difference of principle, between the two liberalisms. Liberalism is one and one alone and it perpetuates itself over time; but each generation has to solve its own problems, which are different from those of yesterday and will be superseded and renewed by the problems of tomorrow. Accordingly, liberals must at all times likewise ask themselves the following question: how can I solve the problems of my time today, in such a manner that the solution adopted will contribute to preserving the supreme good that is the freedom of man, namely his moral and spiritual elevation?

A liberal does not solve today’s problems by repeating, parrot-fashion: freedom! freedom! Therefore liberals can be but are not necessarily believers in an unchecked free market. They do hold such a belief in certain fields, above all as regards customs and excise, for reasons pertaining to economic and moral-political advantages; but they hold no such beliefs in other fields.

Adam Smith, whom those who are economically illiterate proclaim the arch free trader par excellence – and his followers are rather scornfully called Smithian free traders – is also the one who proclaimed that defence of the homeland is far more important than wealth: ‘defence is more important than opulence’;1 in this historical context he defended the Navigation Act, i.e. protection of the merchant navy; furthermore, he fulminated against absentee landlords. I do not know what Adam Smith would write if he were living today, but he would certainly have to enquire into and solve not the problems of 1776, but those of 1945.

Liberals deny that the freedom of man derives from economic freedom, i.e., that economic freedom is the cause and that freedom of the human person in a moral and spiritual sense is the effect. A man who is morally free, in a society composed of men who are profoundly imbued with the dignity of the human person, creates economic institutions that are similar to himself. The machine does not dominate man, nor does it reduce him to slavery or to an extension of itself, save in the case of men who accept living under slavery.

A link between economic freedom and freedom in general, political freedom in particular, does indeed exist. But it is a considerably more subtle link than is declared in everyday propaganda tracts.

It is not true that in modern society men suffer from a lack of freedom attributable to the circumstance that ownership of the means of production is in the hands of a class called ‘capitalist’. For the sake of the argument, let us disregard the fact that in many countries, including a considerable number of Italian regions, or rather, extensive zones of every Italian region, the number of ‘capitalists’ exceeds that of non-capitalists. Let us likewise disregard the incontrovertible fact that the division of society into the two classes of capitalists and proletarians is not even a theoretical abstraction that could perhaps depict some fundamental aspects of the history of mankind: for society presents an enormous variety of classes, many of which are so greatly intertwined that there is hardly a man or a family that does not belong simultaneously to more than one social category. Having thus set aside these considerations – all of which have momentous implications and deserve serious attention – it can be stated, in a nutshell, that no solution, neither the private nor the public approach to ownership of the means of production, is per se capable of helping to solve the problem of freedom.

Neither can it be solved by the system of full private, quiritarian ownership, in which the land, water, mines, industrial plants and waste products are in the absolute possession of the owner, who disposes of them as he pleases without having to be accountable to anyone for his operations. All law-makers in all times and all places have denied the principle that a thing can be in the unlimited disposition of its owner; consequently, limits on the owner’s freedom of action have been established. Stricter limits for mines and water, less strict for land and even more lenient for machinery and supplies. Modern economic analysis, wrongly ignored by socialist writers, dates back to the book written in 1838 by Augustin Cournot;2 it points to ‘monopoly’ as the essential and indeed the single greatest factor responsible for the change whereby ownership of the means of production ceases to render ‘services’ – which involve charging a price equal to minimum cost of the marginal producer – and becomes instead a cause of ‘disservice’ by imposing monopoly prices on the goods produced. This results in useless gains from the point of view of production, and has antisocial effects from the distributive point of view.

Liberals do not come out with Proudhon’s refrain ‘la propriété c’est le vol’ (‘ownership is theft’), for the Proudhonian proposition is false historically and it is shown to be untrue by everyday experience. Rather, they state: ‘le monopole c’est le vol’ (‘monopoly is theft’). Aware as they are of the truth of modern economic analysis, liberals state that economic slavery is not possible wherever there exists competition, where existing entrepreneurs and owners of consolidated agrarian, industrial and commercial enterprises can be challenged by new entrepreneurs, new traders, new speculators who take a chance on the future. At the same time liberals assert that wherever monopoly reigns, one finds production tending to decrease, and the demand for labour and wages also tending to decrease, in parallel with the advent of abnormal profits which become bloated to such gigantic proportions that the distribution of national income becomes severely inequitable, to the benefit of a restricted number of privileged persons and at the expense of the multitudes. Now, liberals are not calling for the intervention of the state against private ownership which stands for saving, independence, self-sufficiency, continuity of the family and a stimulus to economic advancement; nor are they calling for the abolition of private ownership either of consumption goods or of the means of production. Liberals wage no war against saved wealth, nor against wealth obtained in free competition by men endowed with initiative, who venture to take the plunge, accept the risks and succeed. By the same token, liberals do not want to suppress speculation – especially if speculation means farsightedness, adaptation of present means to future needs that beyond the vision of the majority but which the eagle eye of the very few spots before others do, with the added twist that once the speculator had detected such needs, he turns the situation to his own profit and to the benefit of the majority by preordaining the means to satisfy them.

Rather, liberals want to get to the root of the evil, of the social malaise represented by monopoly, for they have become aware of what it is really like. They want the sword of the law to descend inexorably on those who have built a barrier around their enterprise designed to prevent others from gaining access to that closed field. Since many, perhaps the majority of monopolies are artificial, i.e., created by the law itself, liberals demand the abolition of all prohibitions, constraints, excises and privileges whose effect is that not all those who wish to work can genuinely do so, not all those who seek to start up new enterprises, new businesses, or who aim to initiate competition with already firmly established undertakings can succeed in accomplishing their goals.

Away with excises, away with quotas, away with exclusive concessions, away with evergreen stacked patents, away with privileged companies, away with monopolistic companies, away with everything that stifles enterprise and which, under the pretext of disciplining and regulating, compels men to bribe those who grant concessions, permits and licenses.

But it is not merely a question of monopolies created by the law, for if the aim is to abolish such monopolies, all that has to be done is to abolish the law that created them. There are also ‘natural’ monopolies, which originate from the impossibility of multiplying competing enterprises. It is against these monopolies that liberals call for the intervention of the state, which should take over, control or regulate, as the case may be, the running of the monopolistic enterprise. Liberals point out that long before socialization became a fashionable word, two great liberals, Camillo Count of Cavour and Silvio Spaventa, established that the railways should be state-run; liberals further recall that they supported the move by Ivanoe Bonomi in 1916 when he declared that public control, i.e., nationalization, was to be introduced for all Italian water which could be used for hydraulic power or irrigation.

Liberals wish to continue in this direction and are willing to propose and discuss on a case-by-case basis the most suitable way of removing from the private domain whatever industries clearly display monopolistic characteristics. In some cases this will involve direct operation by the state, in others it may require the creation of independent agencies, on yet other occasions that of joint-stock companies in which the state is the majority shareholder, and at certain times there may also be a need to contract the operations out to a private firm, carefully specifying operating conditions and prices. When men of good will sit down around a green baize table they can and must reach an agreement, taking care to avert the two greatest dangers currently looming over the modern economic world. The first is the excessive power of syndicates, consortiums, trusts – whether they be monopolies or syndicates of industrialists or workers – while the second consists in the formation of the most colossal and horrifying monopoly, namely that of the state. The latter case represents the opposite extreme, where absolute private ownership is replaced with absolute ownership by the state, which wields power as the owner of all means of production. No harsher tyranny can be imagined than that which makes the life of man and the subsistence of families depend on the will of one who commands from above. Ascertaining whether whoever is in command has seized power by force or has come to power through elections is of minor importance. What is significant is knowing whether people who want to work and hope to get ahead and improve their standard of living have to turn to a single boss, to a group that has a stranglehold over political power, or whether such citizens can, if they wish, achieve all this by relying on their own strength and appealing directly to the purchasers of the goods and services they believe themselves capable of supplying. Where everything depends on the state, there slavery reigns, there emulation gives way to intrigue, and wheeler-dealers reign triumphant instead of the best of men. This is why liberals want the field of private action to remain distinct from that of public action. Let us engage in discussion as to whether this or that species of economic activity should be left up to private initiative, and under what legal regulations, and whether this or that other species should instead be taken over or contracted out or regulated by the state. The criteria adopted in distinguishing between the two fields make no reference to size: there is no suggestion that small enterprises should be left to the private sector and large enterprises should come under the public wing. Such a distinction is far too crude, for the large enterprise deserves to be brought into the realm of state action only when it is synonymous with a monopoly.

But liberals do not believe that the problem of maximum production is the only problem that needs to be addressed, and that it can be considered without reference to other issues. Even if the presence of a rich variety of private and public types of enterprise succeeds in setting up a mechanism of production capable of achieving the maximum production level, this will simply mean that a maximum has been reached within the limits of existing demand. If there is only one extremely wealthy man in a given country, together with a million destitute individuals, then we can indeed obtain maximum production, but it will be the maximum characteristic of that type of wealth distribution, and would be radically different from the maximum that could be achieved in another country where one man’s income was equal to that of any other man. The maxima would be different, as would the types and varieties of goods produced. We liberals deem bo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Roberto Einaudi

- Editors’ Introduction

- PART I IDEAS AND IDEALS

- PART II INSTITUTIONS

- PART III BATTLES

- PART IV ISSUES

- Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955)

- Message after the Oath (1948)

- On Delays in the Debate and Approval of Draft Bills (1950)

- Notes

- Index of Names

- Index of Subjects