- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

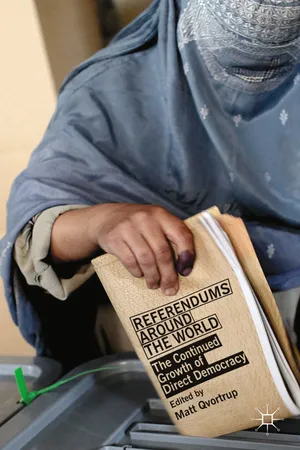

Surveying all referendums around the world since 1793, Dr Qvortrup and contributors provide a thorough account of why and when citizens have been asked to vote on policy issues. Referendums Around the World is essential reading for political scientists and others interested in direct democracy as well as representative government.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Referendums Around the World by Matt Qvortrup in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Referendums in Russia, the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe

Ronald J. Hill and Stephen White

The first time the people of the Soviet Union participated in a referendum also proved to be the last. On 17 March 1991, they were invited to decide on the very future of their country, in the form of a ‘renewed’ union. Some Soviet republics declined to participate, and others added further questions. On 1 December the people of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic precipitated the dismantling of the Soviet Union by using a republican referendum to confirm their wish for independence. Within days, the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus had signed an agreement to establish the Commonwealth of Independent States, rendering the future of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics void. Referendums in other parts of the Soviet ‘empire’ – the Baltic republics and Moldova – and in some of what had been Moscow’s satellites – Poland, for example – had already had significant historical impact. Such a development was scarcely considered a possibility in the centralized, Communist Party-dominated political system. It was certainly not politically relevant. Until the era of perestroika, glasnost’ and democratization in the late 1980s, the Soviet leaders never seemed to sense any need for such a device. However, in the post-Stalin era of ‘the rapid building of communism’ under Khrushchev, and later the period of ‘developed socialism’ under Brezhnev, there developed a substantial scholarly literature about the possibility of making use of this quintessentially democratic mechanism, and the constitutions of a number of Communist-ruled countries, including the Soviet Union itself, made provision for its use in certain circumstances.

The referendum in Communist experience

The founding fathers of the Soviet system, Lenin and Stalin, both spoke positively of the referendum as a means of exercising national self-determination. The constitution of 1936 provided in Article 48 for the government to consult the population in a national poll (referendum), on its own initiative or if one of the constituent republics demanded it. Under Stalin the exercise of such consultation was unthinkable. The same applied in other Communist-ruled countries, such as Albania, where the 1976 constitution twice mentioned the possibility of referendums, without specifying the circumstances in which one might be held. The 1949 Bulgarian constitution (Article 17–10) gave the National Assembly the right to decide on a referendum, but again gave no indication of the circumstances in which it might do so; however, the subsequent ‘Zhivkov’ constitution was adopted by referendum on 16 May 1971 – by a ‘majority’ of 99.7 per cent; 15,477 brave souls out of 6,156,228 who cast their vote declined to endorse the document.

When Khrushchev in the late 1950s launched a broad process of liberalization as part of his vision of the ‘withering away of the state’ on the road to Communism, Soviet scholars were allowed to explore the idea of a referendum alongside other mechanisms of democratic development. A substantial study by the scholar Viktor Kotok (1964), entitled The Referendum in the System of Socialist Democracy, suggested that the referendum would occupy ‘a conspicuous place’ among various ‘new forms of social and state structures’ in this new phase of development. He envisaged ‘a referendum of a new type’ that would exist alongside other new democratic institutions designed to evoke and formulate the will and interests of the whole people. Other scholars joined in, raising pertinent questions about the conduct of referendums in any system: should the result be mandatory or consultative? Should the voting mechanism be identical to that used in elections? Should there be a minimum turnout for a result to be valid? Should a simple or a qualified majority of opinion be required? Should certain constitutional or other weighty matters be subject to a mandatory referendum? The dissident commentator, the historian Roy Medvedev, suggested (1972: 326–7; 1975: 280) that a referendum might be compulsorily held in each constituent republic once a decade to test their willingness to remain part of the USSR. This debate, conducted in the scholarly literature, reveals an unfamiliar openness to ideas in the early post-Khrushchev years, before the stagnation that came to characterize the ‘Brezhnev era’ set in, under the complacent slogan of ‘developed socialism’. The 1977 USSR Constitution made provision in Article 5 for the use of a referendum, but no enabling legislation was adopted until Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the notion of ‘democratization’ from 1987 onwards. Thereafter, alongside strikes, protests and contested elections, it became an important ‘tool for refashioning authority’ (Brady and Kaplan 1994: 175), a crucial element in effecting the break-up of the Soviet Union and establishing new, post-Soviet regimes.

Legislative provision for holding referendums in the Soviet Union was adopted on 27 December 1990, in the form of a law ‘On Voting by the Whole Population (Referendum of the USSR)’, which took immediate effect. It defined a referendum as ‘a means for the adoption, through voting by the whole people, of laws of the USSR and other decisions on the most important questions of the life of the state’ (Article 1). Article 4 stipulated the purposes of this mechanism: (i) to adopt a new law of the USSR; (ii) to amend or annul a law of the USSR, or a part of such a law; (iii) to adopt decisions ‘predetermining the basic content of laws of the USSR or other acts’; or simply (iv) as a means of determining public opinion on ‘the most important questions within the jurisdiction of the USSR’ (Vedomosti 1987, item 387; Vedomosti 1991). A similar law had been adopted by the Russian Federative Republic in October 1990 (Vedomosti RSFSR 1990, item 230). It had taken more than a quarter of a century from the specialist debate on this issue – and more than twice as long since the 1936 Constitution had first referred to a referendum – for the relevant enabling legislation to be enacted. Even then, the legislation was very broad-ranging, from a simple test of public opinion (which might lead no further) to the formal adoption or repeal of a law.

A referendum had already been used in 1987 in Poland, in an exercise in ‘political gimmickry’ by the regime (Lewis 1994: 236), which became in effect ‘the first free referendum in Eastern Europe since World War II’ (Brady and Kaplan 1994: 176). Its result became a turning-point in the fortunes of Communist rule in Poland, in November 1987.

Suffering a seriously flagging economy, the government of General Wojciech Jaruzelski proposed a package of harsh measures aimed at economic reform, sweetened with modest political reforms. These were put to the nation in two referendums on 30 November 1987 – the first since 1946. Solidarity, the independent trade union movement banned in 1981, re-emerged from its underground existence and urged a boycott of the ballot. Turnout fell to 63.8 per cent, on the official figures (opposition estimates put the rate at no more than 30 per cent), significantly lower than the near-universal voting claimed by Communist regimes in elections. A mere 44 per cent voted for the economic reforms, and only 46 per cent for the programme of political liberalization. Both referendums were therefore lost, since neither attained the endorsement of the requisite 50 per cent of the registered electors; but the government went ahead anyway, slightly modifying the speed of implementation of the reforms (Lewis 1994: 236). This failed to resolve the crisis, Solidarity maintained its revival as a national political force, and a year later forced the regime to concede Round Table talks. These led to significant constitutional changes, a partially contested election in which candidates for Solidarity enjoyed spectacular success, and, in August 1989, a government headed by non-Communists for the first time in the region since the Second World War.

Soviet Union, March 1991

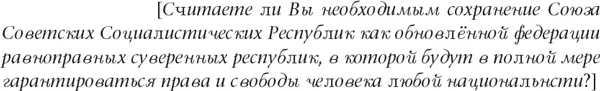

In the growing economic, political and constitutional crisis of the perestroika period (the late 1980s and early 1990s), the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, attempted to use a nationwide referendum to resolve the question of the future of the USSR. Contested elections, following a new electoral law of December 1988, brought about the replacement of established Communist rulers by radical and separatist challengers, some of whom declared the ‘sovereignty’ of their republics and in some cases their intention to secede (notably the three Baltic republics – Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – joined by Georgia, Armenia and Moldavia). This threatened the integrity of the entire Soviet state, and in response Gorbachev proposed to put the matter to the people by presenting the following question in a referendum:

Do you consider it necessary to preserve the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a renewed federation of equal sovereign republics, in which the rights and freedoms of a person of any nationality will be fully guaranteed?

There were several imponderables in this formulation. For example, what was meant by a ‘renewed’ federation? Was the ‘socialist’ identity to continue, and, if so, what did it entail? How would the ‘renewal’ take place? How would the ‘guarantee’ of the rights of members of each nationality be upheld? What were those ‘rights’? And what was the meaning of ‘sovereignty’: would the ‘renewed federation’ exercise sovereignty? If so, what would be the nature of the ‘sovereignty’ of the constituent republics? And more practical questions: how many republics would constitute the renewed federation, given the stated intention to secede and the declarations of ‘sovereignty’ and ‘autonomy’ by second-order territorial units within certain republics, notably Russia (see Sheehy 1990)? Would acceptance freeze existing borders, even where these were disputed? As the debate before the referendum on 17 March 1991 continued around these and other issues, the referendum became something of a last-ditch attempt to salvage a ship that appeared ready to crash upon the rocks of democracy, independence and self-determination of nations.

As the referendum approached, some republics declared the wording of the question unsatisfactory, and they modified its application on their territory. In Kazakhstan, reference was to a ‘union of equal sovereign states’, and in Ukraine voters were asked whether their republic should be part of a union of sovereign states according to the declaration on the state sovereignty of Ukraine of 16 July 1990. Other republics refused to participate, instead organizing separate polls on different dates, seeking endorsement of the policy of national independence. The largest republic, the Russian Federation, and its capital Moscow, together with other republics, provinces and towns, appended questions of specific local interest, including the construction of atomic power stations and the recall of an elected deputy. The initial idea of the referendum – to ‘save’ the Soviet Union, albeit in a different form – was hi-jacked by local politicians for their own purposes, so it could hardly bring about a clear, authoritative resolution of the problem; politically, the impact was devastating for the Union.

In fact, it became a weapon in the highly personal struggle between Gorbachev, representing the centre and the old Communist Party, on one side, and, on the other, Boris Yeltsin, symbol and leader of the democratizing forces, who were willing to see the country break up if that was the ‘democratically expressed’ will of its various peoples. And, to outflank Gorbachev, voters in the Russian Federation were asked to endorse the idea of a directly elected president of the Republic.

Encouraged by vigorous campaigning on both sides, including strong anti-Gorbachev rhetoric from Yeltsin and his supporters in the radical camp, voters turned out in record numbers over a geographical area of record size, but the outcome allowed all sides to claim victory. Out of more than 185 million registered voters, 80 per cent cast their ballot, and 76 per cent of these supported Gorbachev’s position of retaining a ‘renewed’ union; however, 22 per cent voted against – over 32 million votes – and there were 2.75 million invalid votes (figures derived from Izvestiya 28 March 1991: 1, 3). Well over half of the electorate, it turned out, had supported the ‘renewed federation’, with particularly strong support in the Central Asian republics; far less supportive were urban, industrialized areas, notably Russia. The central authorities were disappointed to find that Moscow and Leningrad, the country’s two principal cities, voted ‘yes’ by tiny minorities (Nezavisimaya gazeta 21 March 1991).

Gorbachev claimed a mandate to negotiate a new treaty of union, to be signed on 20 August. This precipitated the failed coup against him on the day before that date. On the other side, Yeltsin won the support of 69.9 per cent of the 75.4 per cent who voted on the question of a directly elected president of Russia, and three months later he won a landslide victory against five other candidates. This gave him a popular, and recent, mandate that Gorbachev, as Soviet president, lacked, and in subsequent months he acted to reduce the scope and effectiveness of central authority, and to prevent the Soviet Union’s institutions, including its ministries, from functioning on the territory of Russia.

The fate of the Soviet Union was sealed when on 1 December 1991 Ukrainian voters used a further referendum to determine the question of independence. The republic’s political elite, including the Communist Party leader Leonid Kravchuk, had adopted a nationalist stance and supported separation, despite the republic’s 70 per cent support for the ‘renewed union’ in the March referendum; and now the citizenry chose independence by a margin of 90.3 per cent on a turnout of 84.1 per cent. Within a month, Gorbachev resigned as president of the USSR, the Soviet Union was dissolved, and the Commonwealth of Independent States created as a means of either continuing some form of union or managing an orderly disintegration.

The referendum in the transition from Communism

That mixed experience of the referendum under Communist rule did not inhibit post-Communist elites in making it part of their new, ‘democratic’ constitutional arrangements. It serves a number of purposes, and politicians frequently feel tempted to use it as a mechanism for breaking a political or constitutional deadlock. As the experiences of Jaruzelski in Poland and Gorbachev in the Soviet Union show, it can sometimes backfire, and fail to resolve the problem in the way its promoters hope. The post-Communist era has provided further examples. Moreover, it is also interesting that this impeccably ‘democratic’ and ‘authoritative’ device is deployed as often in regimes that are openly undemocratic as in those that strive to meet high standards of democratic practice.

Post-Soviet Russia was in some ways a test case of using a referendum to overcome a political impasse. Boris Yeltsin enjoyed a mandate as the first democratically elected president of Russia, with substantial powers and a sense of authority that derived from that mandate, from his success in facing down the plotters in the 1991 coup against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, and from his subsequent use of his authority in bringing about the fall of the Soviet Union. In independent Russia, he intended to use that authority to bring about rapid economic change, including a freeing of prices and opening up the economy to competition from abroad. This threatened rapid inflation, serious dislocation, the erosion of savings, a collapse in popular living standards, factory closures and massive unemployment. The circumstances were dire; the consequences of such a ‘big bang’ approach potentially catastrophic for millions. On the other hand, parliamentary deputies – also possessing a mandate of sorts, since they too had been elected in competitive elections, and certainly facing re-election at the end of their term – wished to prevent these consequences of reform. They also, perhaps with reason, feared for their own position and that of the parliament (the Congress of People’s Deputies) in the new situation. Thus, presidential decrees were overturned by the parliament, while the president expanded his office establishment. This was a clash between parliamentary and presidential democracy, over which no choice had been made. Both sides enjoyed powers established in the 1978 RSFSR Constitution, which had been amended by accretion into a contradictory document that was proving incapable of permitting effective government.

An initial attempt to resolve the situation came on 25 April 1993, through a referendum proposed by the president and authorized by the Congress of People’s Deputies. Four issues faced the electors: confidence in Yeltsin as president; support for the programme of radical economic reforms; the calling of early presidential elections; and similar early elections to the parliament. The media largely supported Yeltsin, and he used his authority to ‘bribe’ significant constituencies, promising increased grants to students, better pensions, and improved salaries for certain significant groups of workers. The outcome was mixed: on a respectable turnout of something over 60 per cent, Yeltsin won endorsement for his presidency and his economic programme – evidently a mandate for reform (see Tolz and Wishnevsky 1993); but there was insufficient support for early elections. Opinion polls taken at the time suggested that the population was divided over the way forward, with 30 per cent support for both a ‘strong president’ and a ‘strong parliament’ (see Rose, Boeva and Shironin 1993). In any case, the vote was not uniform across the country, and some regions had added questions of their own, in a repetition of the March 1991 Soviet referendum (Tolz and Wishnevsky 1993).

The stalemate continued until 21 September 1993, when President Boris Yeltsin decreed the suspension of parliament, deployed military force to shell the building, and on 12 December held a referendum – he referred to it as a ‘plebiscite’ – in conjunction with elections in a political exercise of doubtful legitimacy, if not legality. He presented a new constitution for endorsement, allowing no discussion of its detail, while simultaneously holding elections to institutions that would come into being only if that constitution were adopted. Such a series of actions, taken in a context of extreme political conflict, seems hardly designed to guarantee a smooth transition to a law-based democracy. The results, too, were politically inconclusive. Turnout was officially stated to be 54.8 per cent, and only 56.6 per cent of those who voted approved the new constitution – a distinct minority (about 31 per cent) of the total electorate; in a number of territorial units a majority voted against. Yet those results were deemed to constitute endorsement; the new constitution came into force, the new political institutions were inaugurated, and the president henceforth exercised enormous powers. The constitution itself stated (Article 3) that ‘The supreme direct expression of the authority of the people is the referendum and free elections’ and provided (Article 135) for the adoption of any replacement by referendum (or by a Constitutional Assembly).

In the early years of the independent existence of the Russian Federation, similar use was made of the referendum at republican level, which potentially challenged the integrity of the state. In Chechnya, following local elections, the authorities declared their independence from Moscow in November 1991, without a referendum, and refused to participate in Russian elections or the referendums of April and December 1993. In Tatarstan, one of Russia’s largest republics, citizens were asked on 21 March 1992 whether they agreed that ‘the republic of Tatarstan is a sovereign state, a subject of international law, building its relations with the Russian Federation and other republics and states on the basis of treaties between equal partners’ – a rather profound question that might exercise the brains of eminent lawyers. Some of the possible implications, which had evidently been raised in discussion as the referendum approached, were clarified in an explanatory statement by the republic’s Supreme Soviet. The result – endorsement of the proposition – led to negotiations and eventually an agreement between the authorities in the republic and the federal authorities in Moscow that defused the threat of secession (see Khakimov, no date). Subsequent political and constitutional changes in Russia have evidently caused the threat of secession to secede. In 2003 Tatarstan adopted legislation setting out regulations for the conduct of referendums on its own territory (Zakon 2003).

Elsewhere, the referendum was used in the transition from Communist rule to a post-Communist constitutional arrangement. Thus, a new constitution was approved in Romania by referendum on 8 December 1991. A referendum in Hungary on 26 November 1989 was called to resolve a matter raised at the Round Table talks two months earlier: whether a new state president should be elected immediately by the population (a course favoured by the former Communist Party) or by a newly elected parliament (as the opposition parties preferred, since the campaign would raise their profile). The electorate favoured the latter course, but by a mere 50.1 per cent majority on a turnout of 55 per cent; three other questions, including a proposal to ban Communist Party activity at the workplace, received overwhelming positive endorsement. A further referendum on 29 July 1990, to institute direct elections to the presidency, evoked a derisory turnout of 13.8 per cent and was declared invalid. Similarly, in Slovakia, a turnout of less than 19 per cent invalidated a referendum on the privatization of economic enterprises. Such examples indicate that, in a time of momentous political change, including the novel experience of contested elections at parliamentary, provincial ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Theory, Practice and History

- 1. Referendums in Russia, the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe

- 2. Referendums in Western Europe

- 3. Referendums in Switzerland

- 4. Referendums and Initiatives in North America

- 5. Direct Democracy in Latin America

- 6. Referendums in Africa

- 7. Referendums in Asia

- 8. Referendums in Oceania

- 9. Conclusion

- Appendix A: Referendums Around the World

- Appendix B: Referendums on Devolution and Self-Government in Subordinate Territories

- Index