- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Politics of Europeanization and Post-Socialist Transformations

About this book

This study examines conflicts arising from the dual processes of Europeanization and post-socialist transformations, from gaining independence in 1991 to facing the current economic crisis. Through an in-depth comparison of Estonia and Slovenia over time, it shows how elite actors within these two very different welfare capitalist states resisted EU pressures to change their cohesive and successful national models.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Europeanization and Post-Socialist Transformations by N. Lindstrom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Abstract: The chapter sets out the book’s main premise: that post-socialist transformations and Europeanization, instead of complimentary processes, can be politically incompatible, leading to different types of political conflicts over European integration. Comparing two most different welfare capitalist models, Estonia and Slovenia, the book argues that conflicts over European integration are shaped by collective ideas underlying a country’s particular post-socialist transformation path and whether the EU is perceived to fall to the left or right of the national political economic status quo.

Keywords: capitalist models; Central and Eastern Europe; Estonia; European Union; post-socialist transformation; Slovenia

Lindstrom, Nicole. The Politics of Europeanization and Post-Socialist Transformations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137352187.0002.

If one seeks to analyze the interplay between transnational and domestic factors, few better sites exist than the post-socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). This is a region where far reaching domestic changes brought about by the demise of state socialism have gone hand-in-hand with rapid integration into a trans-nationalizing economy, the concurrence of which is unparalleled in other regions of the world. Here political economic paths have not only been shaped by domestic political conflicts and compromises, but have also been influenced by external actors, most significantly, but not limited to, the European Union (EU). If scholars of comparative post-socialist transformations were faulted for paying scant attention to external factors, scholars of EU conditionality have tended to err in the opposite direction. That is, studies of European influence in CEE often focus on the effectiveness of EU conditions at the expense of understanding the diverse political economic contexts in which EU influence plays out.

This book argues that post-socialist transformations and Europeanization, instead of complimentary processes, can be politically incompatible, leading to different types of political conflicts over European integration. These conflicts, I argue, are shaped by collective ideas underlying a country’s particular post-socialist transformation path. With the demise of communist regimes, some CEE states followed a more radical neo-liberal transformation path involving rapid liberalization, deregulation, and privatization. Others fashioned a more gradualist strategy that used state power to simultaneously build market economies while protecting domestic industries and preserving social cohesion. Today, like in Western Europe, we can observe a variety of welfare capitalisms among CEE states (Bohle and Greskovits, 2012; Nölke and Vliegenthart, 2009). Scholars of Western Europe have demonstrated how welfare capitalist models shape member state positions towards Europe. For example, in more liberal market economies such as the United Kingdom, European integration has traditionally been portrayed in Thatcher’s terms as ‘socialism through the back door’. In more social market economies such as Sweden, on the other hand, further integration had been depicted as ‘Anglo-Saxon capitalism through the back-door’ (Hix and Goetz, 2000, pp. 4–5). In other words, positions on European integration depend in part on whether the EU is perceived to fall to the left or right of the national status quo. This book suggests that we can observe similar patterns of political conflict over European integration among post-socialist CEE states.

The book considers this argument through a comparison of two new EU (and euro) member states: Estonia and Slovenia. Each of the two small, newly independent states was heralded as an economic success story upon joining the EU. But each state can attribute its economic success to a very different transition strategy: Estonia pursued the most liberalizing reform agenda of all CEE states, and Slovenia one of the most gradualist and interventionist. With the start of formal EU accession negotiations in 1998, each candidate was pressured to adapt its emerging market economy differently. In general, the EU pushed Estonia to de-liberalize its economy, whereas in Slovenia it pressed for further liberalization (Bohle and Greskovits, 2012, p. 94). In each case EU conditions encountered significant domestic opposition. National ‘architects of transition’, technocrats and intellectuals who played instrumental roles in forging initial transformation paths, mobilized to defend their models against the alleged threat posed by Brussels. Moreover, given that political and economic transformations in each state occurred simultaneously with the process of nation-state building (in Slovenia’s case for the first time in its national history), the identity of the nation-state became inextricably linked to the type of economic model pursued. That each country was heralded by outside observers as an economic ‘success’ contributed further to the impetus of elites and electorates alike to defend its economic model against any external threat.

The book develops this argument by tracing the process through which elites in Estonia and Slovenia ascribed different meanings to Europe and the EU over time. In the earliest stages of transition, I show in Chapter 3 how economic nations were construed more in opposition to federal socialist pasts (Soviet and Yugoslav respectively) than to any substantive, proactive ideas about Europe or the EU. Chapter 4 goes on to show how this changed once each state entered formal EU accession negotiations, when the EU moved from wielding ‘passive’ to ‘active’ leverage (Vachudova, 2005). Now ‘architects of transition’ began to portray particular EU pressures as threatening the core values underlying their respective post-socialist transformation paths. Chapter 6 considers the impact of the global financial crisis and subsequent fiscal crisis on Estonia and Slovenia. It shows that while the crisis hit each state hard, marking the most significant threat to their particular welfare capitalist models since gaining independence, the Slovenian model has undergone the most significant change. The book concludes by identifying the broader theoretical contributions of the book to our understanding of the role of ideas in our understanding of the politics of Europeanization and identifies areas for future research.

2

The Politics of Europeanization

Abstract: The chapter sets out a framework for analyzing how ‘Europe’, and in particular the EU, is contested within and across an enlarged EU composed of diverse welfare capitalist models. Understanding European integration as an open-ended, contingent, political project, the chapter considers two dimensions of EU contestation: (a) left/right ideas on state intervention in the economy and (b) market-making versus market-shaping ideas on European integration. The chapter offers a constructivist political economy approach to EU political contention considering how domestic actors, namely post-socialist intellectual technocratic elites, ascribe the EU with different meanings depending on particular national, collective understandings about the ideal relationship between the state, market, and society.

Keywords: domestic actors; economic nationalism; European integration; transnational capitalisms; varieties of capitalism

Lindstrom, Nicole. The Politics of Europeanization and Post-Socialist Transformations. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137352187.0003.

This chapter sets out a framework for analyzing how ‘Europe’, and in particular the EU, is contested within and across an enlarged EU comprised of diverse welfare capitalist models. Underlying the framework is an understanding of European integration as an open-ended, contingent, political project. In particular, it builds on models of political contention in the European Union (EU) that focus on two sets of ideological factors: the appropriate level and degree of state intervention in the economy (the traditional left/right divide) combined with ideational struggles over whether European integration should be driven by market-making versus market-shaping principles. To understand ideational conflicts over the EU, we cannot limit our analysis to member states competing within a supranational sphere (the functional approach) or to party competition at the domestic level (the Europeanization approach). The chapter suggests that we need a more dynamic understanding of the politics of Europeanization that examines how domestic actors, namely intellectual technocratic elites, ascribe the EU with different meanings depending on particular national, collective understandings about the ideal relationship between the state, market, and society.

The politics of Europeanization

If national leaders long counted on a ‘permissive consensus’ among their citizens on matters related to European integration, since at least the passage of the Single European Act leaders face an increasing ‘constraining dissensus’ (Hooghe and Marks, 2008). From French, Dutch, and Irish voters voting down constitutional treaties in public referenda to the rise of Euroskeptic parties, European citizens appear less willing to give their leaders free rein in matters related to the EU (Ivaldi, 2006). Questions concerning the appropriate scope of EU competencies, its democratic legitimacy, and indeed its very existence are the subject of growing political debate (Wilde and Trenz, 2012). Political contention in the EU falls along two dimensions. What Mair (2007) terms the ‘functional dimension’ encompasses conflicts over the EU polity, including its underlying social purpose, degree of institutionalization, and future trajectory. The ‘Europeanization dimension’, on the other hand, involves conflicts over the infiltration of EU rules and norms into the domestic sphere.

EU scholars who study political contention tend to focus on one of these two dimensions: some examine conflicts within the European Parliament and other supranational arenas (Hix, Noury, and Roland, 2007) and others examine patterns of political conflicts within domestic representative channels, focusing largely on political parties and public opinion (Szczerbiak and Taggart, 2008). Yet the two dimensions are interrelated. As Mair (2007, p. 9) suggests, without greater consolidation and extension of EU competencies, there would be little concern about EU penetration into domestic affairs. Likewise, domestic concerns about the penetration of EU rules and norms feed back into political contestation at the EU level. The politics of Europeanization can thus be viewed as a combination of these two dimensions. Understanding the supranational and national levels as interconnected does not treat the EU as an end in itself (as it is in typical European integration approaches) or as top-down constraint (as in Europeanization approaches). Instead it points us towards a more dynamic understanding of the politics of Europeanization, whereby the meaning of the EU is socially mediated within diverse national contexts (Hay and Rosamond, 2002).

In order to analyze patterns of political contention, we can start by mapping different positions on the EU, or sets of ideal typical ideas, beliefs, and principles about the underlying social purpose of European integration (Parsons, 2003; Jabko, 2006). The first relevant value dimension is along traditional left/right lines. In particular, we can differentiate among different ideas about how far the state should intervene in the market to promote collective goods (Hix, 1999, p. 73). A second dimension concerns ideas over the appropriate relationship between the sovereign state and supranational institutions. On one end of the continuum lies the belief that authority should reside in directly accountable national governments with few or no transfer of competencies to the European level, and on the other an allegiance to neo-functionalist ideas in which the gradual transfer of competencies to the EU should eventually lead to a single European polity and identity.

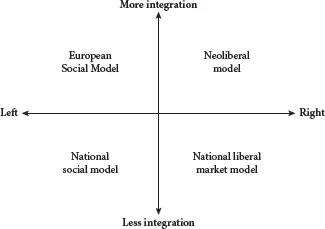

Hooghe and Marks (1999) offer a two-dimensional model of the EU political space whereby the left/right dimension and the sovereignty/integration dimension jointly structure actors’ positions on the EU (Marks and Steenbergen, 2004, p. 10). They argue that as the EU seeks to expand its competencies over social market-shaping matters, left-leaning actors will become more pro-integration (what they term ‘regulated capitalism’) and right-leaning actors more anti-integration (‘neo-liberalism’). Figure 2.1 adapts Hooghe and Marks’ model to consider a wider range of positions. Left-leaning positions share in common a principled attachment to the idea that markets should be regulated in order to promote a range of collective goods. But they differ over the most appropriate site for exerting such authority. A ‘national social model’ advocates a strict decoupling between market integration at the European level and social protection at the national level (Scharpf, 2002). A ‘European social model’ position, on the other hand, is more skeptical of such a tidy decoupling. It suggests that as economic integration places increasing direct and indirect pressures on national welfare states, the only effective means of maintaining regulations and social protections is furthering social integration at the EU level.

Turning to the right-leaning end of the spectrum: right-leaning actors share an underlying belief in reducing or eliminating regulations and other restrictions on the free movement of goods and capital. But they differ over how truly free markets can most effectively be achieved. Advocates of a ‘national market liberal model’ argue that the best means of ensuring open markets is through global integration, ideally sidelining or, in some cases, exiting the EU. The UK Independence Party exemplifies such an approach. Those who support a ‘neoliberal model’, however, argue that furthering negative- or market-making integration at the EU, while obstructing social integration, presents the most suitable means of making member state governments more responsive to the discipline of transnational market forces.

FIGURE 2.1 Political economic positions on the EU

Differentiating among these four ideal types makes two important contributions to mapping different types of political contention in the EU. First, many studies of Euroskepticism measure the intensity of anti-EU opinion, whether ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ (Szczerbiak and Taggart, 2008), ‘specific’ or ‘diffuse’ (Kopecky and Mudde, 2002). But such studies often fail to capture the content of this opposition. In other words, what type of ‘Europe’ in particular do actors oppose, whether specifically or diffusely? Second, in capturing variation in beliefs about the different goals of European integration (market-enhancing or market-shaping integration) and the means of achieving them (through European or national-level sites of authority), the model combines both the functional and Europeanization dimensions of political contestation. That is, ideological conflicts over the future trajectory of the EU are not limited to ‘regulated capitalism’ versus ‘neoliberalism’, as Hooghe and Marks (2008) and others suggest. Actors on the left and the right also disagree over which site of authority (national or EU) that political economic goals are best achieved.

To analyze these patterns of contestation, the book focuses on how different types of national welfare capitalisms shape positions on the EU. It builds on studies that focus on welfare capitalisms as an important intervening variable in mapping conflicts over European integration. Brinegar, Jolly and Kitschelt (2004: 86) show, for example, how different varieties of capitalism determine citizens’ opinions on the EU. They find that in social democratic comprehensive welfare states such as Sweden, Denmark, and Finland left-leaning voters tend to oppose further EU integration. In liberal residual welfare states such as the United Kingdom, on the other hand, right-leaning voters are most opposed. In Christian democratic welfare states such as Germany, they find little right-left polarization on the EU issue. In another study, Ray (2004) finds that the more favorably voters view their current national policies, such as levels of spending on social welfare protections, the more likely they are to oppose ceding authority to the supranational level. A key conclusion of such studies is that critics of Europeanization are united by a desire to preserve the national status quo against any further intrusion of European rules and norms.

Focusing on types of national welfare capitalisms as a key determinant of European integration positions contributes to our understanding of political contestation in the EU in a number of ways. For one, it challenges conventional wisdom that the most strident critics of further integration are those on its losing end, such as lower skilled workers unable to compete in more open and integrated markets (Gabel, 1998). Instead it suggests that it may indeed be the ‘winners’ across European societies who are most reluctant to ‘rock the boat’ by transferring more authority to supranational institutions (Ray, 2004, p. 58). Second, while a majority of studies focus on political parties or public opinion, a political economy approach is well suited to analyzing the role of other domestic actors, such as political elites, public intellectuals, labor unions, business associations, and other civil society groups (Vasilopoulou, 2013). Menz (2003), for example, shows how trade unions in more liberal states are more inclined to advocate re-regulation at the EU level than their counterparts in more corporatist member states who fear a transfer of authority to the EU level would erode strong existing domestic regulations.

Finally such an approach acknowledges that while European integration has led to convergence in numerous policy areas, the EU remains comprised of diverse national welfare state models. As Scharpf (2002, p. 651) suggests, citizens are attached to, or ‘embedded in’ (Polanyi, 1944), particular historical understandings of the ideal relationship between the state, market, and society. These collective beliefs, in turn, carry a high degree of political salience, as citizens expect their states to protect them against the unfettered forces of market liberalization. Thus, opposition to European integration can be driven by concerns that the EU not only poses a threat to one’s personal circumstances but also to the very social foundations of a particular national welfare state model.

The politics of Europeanization in CEE

A main contention of the literature on Europeanization of post-...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Politics of Europeanization

- 3 The Politics of Europe (1989–1996)

- 4 The Politics of Conditionality (1997–2004)

- 5 The Politics of Crisis (2007–2014)

- 6 Conclusions

- References

- Index