eBook - ePub

From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 1

The Theory and Research on Occupational Stress and Wellbeing

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 1

The Theory and Research on Occupational Stress and Wellbeing

About this book

A comprehensive collection by Professor Cary Cooper and his colleagues in the field of workplace stress and wellbeing, which draws on research in a number of areas including stress-strain relationships, sources of workplace stress and stressful occupations. Volume 1 of 2.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Stress to Wellbeing Volume 1 by C. Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theory and Reviews of Stress and Wellbeing

1

Occupational Sources of Stress: A Review of the Literature Relating to Coronary Heart Disease and Mental Ill Health

Cary L. Cooper and Judi Marshall

Felton & Cole (1963) estimate that all cardiovascular diseases accounted for 12 per cent of the time lost by the ‘working population’ in the US, for a total economic loss of about $4 billion in a single year. A report (1969) by the Department of Health and Social Security in the UK shows, as Aldridge (1970) indicates, that the sum of incapacity for men suffering from mental, psychoneurotic and personality disorders, nervousness, debility and migraine headache accounted for 22·8 million work days lost in 1968 alone (second only to bronchitis in the league table of illness and lost working days). Coronary heart disease and mental ill health together, therefore, represent a serious cost for industry both in human and financial terms.

There is a growing body of evidence from studies in experimental laboratory settings (Kahn & Quinn, 1970) and in the workplace (Margolis, Kroes & Quinn, 1974) to suggest that occupational stress is a causal factor in these diseases. By occupational stress is meant negative environmental factors or stressors (e.g. work overload, role conflict/ambiguity, poor working conditions) associated with a particular job. In addition to the environmental precursors, inherent characteristics of the individual and his behaviours may also contribute to occupational ill health. In fact, as Jenkins (1971a) has suggested, the early clinical studies of psychosomatically oriented General Practitioners and psychiatrists led to a number of theories about a predisposing state of neuroticism being confronted by environmental stressors leading to reaction of anxiety, changes in cardiovascular function and, in time, to coronary heart disease or mental ill health.

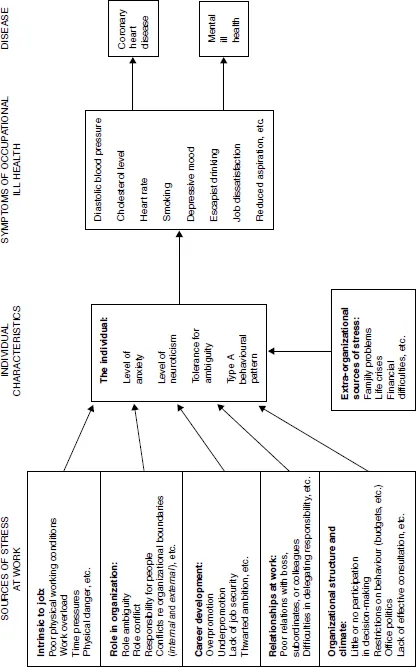

There are, therefore, two central features of stress at work, the interaction of which determines either coping or maladaptive behaviour and stress-related disease (Cooper & Marshall, 1975): (1) the dimensions or characteristics of the person and (2) the potential sources of stress in the work environment; or as Lofquist & Dawis (1969) have labelled this interaction The Person–Environment Fit. There is, however, a third set of extra-organizational variables which can also be sources of stress. These are not linked directly to the individual’s characteristics or the work environment but are related to outside relationships and events, for example, family problems, financial difficulties, life crises (death in the family), etc., which have an impact in the workplace. In Figure 1.1 we provide a diagram which will highlight a model of stress at work which incorporates these concepts.

It is our intention here to examine the stress research literature linking environmental and individual sources of stress to physical and mental disease or illness. We are attempting this in the hope that we will be able to reveal where much of the work has been done and where the gaps lie. In addition, since much of the research has been carried out ‘within’ particular disciplines (i.e. psychology, management, sociology, medicine) and not ‘between’ disciplines, it is hoped that we may indicate the potential of interdisciplinary work in this field and begin to encourage this development.

Before embarking on this review, it might be helpful to note that many of the stress studies over the last 10–15 years have utilized two primary indices of occupational disease, coronary heart disease (CHD) and mental ill health (MIH). A more limited number of studies have focused on other physical illnesses thought to be stress-related, such as peptic ulcers, respiratory diseases and allergies, but these have not been as thoroughly researched in respect to social and psychologic stressors as heart disease or mental ill health. We have concentrated on the CHD and MIH studies primarily but have included the others, where they have contributed a new dimension or perspective to this topic. It might be added here that our literature review covered all the journals incorporated in the MEDLARS literature-retrieval system of the US National Library of Medicine, which includes most of the relevant medical and social science journals.

We should like to preface this review with a brief summary of some of the methodological problems encountered in some of the studies to follow. In the main text detailed criticism of individual studies has been kept to a minimum to allow breadth of coverage; we hope here, however, to forewarn the reader of the difficulties of interpretation of the research reported. Some of the methodological shortcomings are:

(1)Use of correlational analysis

(a)Most of the studies reported rely heavily on correlational data for their conclusions. The inferences about causality which can be drawn are, therefore, limited.

(b)Correlational analysis also fails to point out the role of intervening variables. A causal chain is not necessarily only two variables long as many studies would have us believe.

(2)Confusion of dependent and independent variables

By using the term ‘stress’ too widely – to denote pressure on the individual (e.g. work overload), its’ effects (e.g. poor work performance), and also his reactions (e.g. escapist drinking) – researchers have contributed to conceptual and definitional confusion in this area. For an attempt to remedy this see Kagan & Levi (1974) and their ‘theoretical model for psychosocially mediated disease’.

(3)Definition and measurement of variables

(a)Should ‘stress’ be measured objectively (e.g. diastolic blood pressure) or subjectively (e.g. self-report)?

(b)How adequate are the currently used measures of MIH?

(c)Some independent variables are susceptible to contamination by the dependent variable being studied. In retrospective studies of CHD deaths, for example, occupation (usually taken from the death certificate) may have been directly affected by a preceding illness.

(d)Use of broad categories (e.g. occupational levels) can obscure meaningful differences between groups and make the comparison of findings between studies more difficult.

(4)Samples

(a)Some researchers attempt to generalize from an intensive study of a small highly specific sample; others, from large-scale samples using simplistic survey techniques.

(b)It is difficult to decide what represents an adequate control group: the general normative population; patients suffering from (supposedly) non stress-related diseases; or the subjects at a ‘normal’ time in their lives?

(5)Retrospective studies

(a)Retrospective studies are particularly likely to suffer from the drawbacks mentioned above; the current trend towards prospective studies is, therefore, encouraging.

Environmental stressors at work

There are a large number of possible environmental sources of stress at work, as one can see from Figure 1.1: factors intrinsic to a particular job (e.g. air traffic controller), role in organization, career development, relationships at work, and just ‘being’ in an organization:

Factors intrinsic to a job

A great deal of work has been done linking the working conditions of a particular job and its relationship to physical/mental health. Kornhauser (1965) found, for example, that poor mental health was directly related to unpleasant work conditions, the necessity to work fast and to expend a lot of physical effort, and to excessive and inconvenient hours. There is increasing evidence (Marcson, 1970; Shepard, 1971), that physical health, as well, is adversely affected by repetitive and dehumanizing environments (e.g. paced assembly lines). Kritsikis, Heinemann & Eitner (1968), for example, in a study of 150 men with angina pectoris in a population of over 4000 industrial workers in Berlin, reported that more of these workers came from work environments employing conveyor-line systems than any other work technology. Although we possess enough indirect data to suggest that paced assembly lines are a potential danger to occupational health (both mental and physical) not enough controlled work, with multiple health criteria measures, is available to draw any firm conclusions – research in this area is desperately needed.

Figure 1.1 A model of stress at work

On the other hand, research into work and overload has been given substantial empirical attention. French & Caplan (1973) have differentiated overload in terms of quantitative and qualitative overload. Quantitative refers to having ‘too much to do’, while qualitative means work that is ‘too difficult’. (The complementary phenomena of quantitative and qualitative underload are also hypothesized as potential sources of stress but with little or no supportive research evidence.) Miller (1960) has theorized, and Terryberry (1968) has found, that ‘overload’ in most systems leads to breakdown, whether we are dealing with single biological cells or individuals in organizations. In an early study, French & Caplan (1970) found that objective quantitative overload was strongly linked to cigarette smoking (an important risk factor or symptom of CHD). Persons with more phone calls, office visits, and meetings per given unit of work time were found to smoke significantly more cigarettes than persons with fewer such engagements. In a study of 100 young coronary patients, Russek & Zohman (1958) found that 25 per cent had been working at two jobs and an additional 45 per cent had worked at jobs which required (due to work overload) 60 or more hours per week. They add that although prolonged emotional strain preceded the attack in 91 per cent of the cases, similar stress was only observed in 20 per cent of the controls.

Breslow & Buell (1960) have also reported findings which support a relationship between hours of work and death from coronary disease. In an investigation of mortality rates of men in California, they observed that workers in light industry under the age of 45, who are on the job more than 48 hours a week, have twice the risk of death from CHD compared with similar workers working 40 or under hours a week. Another substantial investigation on quantitative workload was carried out by Margolis et al. (1974) on a representative national sample of 1496 employed persons, 16 years of age or older. They found that overload was significantly related to a number of symptoms or indicators of stress: escapist drinking (r = 0·06), absenteeism from work (r = 0·06), low motivation to work (r = 0·26), lowered self-esteem (r = 0·10), and an absence of suggestions to employers (r = 0·17). Although these coefficients are significant, they are very small indeed, contributing between less than 1 per cent to a maximum of 5 per cent of the variance. Quantitative overload is obviously a potential source of occupational stress, as other studies (Quinn, Seashore & Mangione, 1971; Porter & Lawler, 1965) also indicate, but on the evidence available it may not, by itself, be a main factor in occupational ill health.

There is also some evidence that (for some occupations) ‘qualitative’ overload is a source of stress. French, Tupper & Mueller (1965) looked at qualitative and quantitative work overload in a large university. They used questionnaires, interviews and medical examinations to obtain data on risk factors associated with CHD for 122 university administrators and professors. They found that one symptom of stress, low self-esteem, was related to work overload but that this was different for the two occupational groupings. Qualitative overload was not significantly linked to low self-esteem among the administrators but was significantly correlated for the professors. The greater the ‘quality’ of work expected of the professor the lower the self-esteem. They also found that qualitative and quantitative overload were correlated (r = 0·25 and r = 0·42 respectively) to achievement orientation. And more interestingly, in a follow up study, that achievement orientation correlated very strongly with serum uric acid (r = 0·68) (Brooks & Mueller, 1966). Several other studies have reported an association of qualitative work overload with cholesterol level; a tax deadline for accountants (Friedman, Rosenman & Carroll, 1958), medical students performing a medical examination under observation (Dreyfuss & Czackes, 1959), etc.

French & Caplan (1973) summarize this research by suggesting that both qualitative and quantitative overload produce at least nine different symptoms of psychological and physical strain; job dissatisfaction, job tension, lower self-esteem, threat, embarrassment, high cholesterol levels, increased heart rate, skin resistance, and more smoking. In analysing these data, however, one cannot ignore the vital interactive relationship of the job and employee; objective work overload, for example, should not be viewed in isolation but relative to the individual’s capacities and personality. It should also be noted that since qualitative and quantitative work overload measures stem from perceptions of the subject, they may be influenced by the subject’s personality predispositions (e.g. nAch people).

Role in organization

Another major source of occupational stress is associated with a person’s role at wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Part I Theory and Reviews of Stress and Wellbeing

- Part II Stress–Strain Relationships

- Part III Sources of Workplace Stress

- Part IV Stressful Occupations

- Part V Research Methods in Stress and Wellbeing

- Index