- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Housing policy has been central to the economic success stories of the major East Asian economies as well as a pillar of social and welfare provision. This book explores not only the development of their distinctive approach, but also the challenges posed in recent years, and currently, by rapid socio-economic and demographic change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Housing East Asia by J. Doling, R. Ronald, J. Doling,R. Ronald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Changing Shape of the East Asian Housing Model

Introduction

Notwithstanding detailed differences in housing policies, as well as the development gap between the southerly and most eastern regions, the major East Asian economies can be seen as sharing a common housing model, distinct from those of western economies. In East Asia, housing interventions historically focused on the high volume production of apartments for working, male breadwinner households. Rates of housing output have been phenomenal in most cases, with the rapid expansion of construction programmes reflecting the abilities of development-orientated East Asian governments to appropriate land and mobilize the resources of public agencies and private corporations in the supply of new housing. The main priority was to sustain the express pace of modernization, urbanization and economic expansion. State plans sought to clear slum housing, increase land values and promote high-speed growth. Individual housing needs were not irrelevant, although political and economic logic usually dictated that economically productive households were prioritized rather than the poor or vulnerable. Approaches thus reflected the features of both developmental states (see Johnson, 1982; Wade 1998) and productivist welfare regimes (Holliday, 2000; Kwon, 2005; Kwon and Holliday, 2007). For reasons explored throughout this book, home ownership became strongly embedded in this East Asian model. Based on the primacy of national economic growth objectives, home ownership was promoted as a means of, on the one hand, contributing directly to economic growth through the motor of the construction industry, and, on the other, supporting a low-taxation, low-public-expenditure economy with minimal social protection measures through the support of the family (Lee, Forrest and Tam, 2003; Ronald 2007, 2008; Ronald and Doling, 2010, 2012).

In recent years, however, with the undermining of traditional developmental logic and the growing volatility of housing markets generated by intensified globalization, the traditional housing model has been challenged. In the last decade or so (since the 1997–1998 Asian Financial Crisis in particular), private real estate interests locally, and neo-liberal prerogatives more globally, have asserted a firmer grip on policy agendas (Park, Hill and Saito, 2012). At the same time, social housing has also come to the fore as public welfare spending and cover has expanded (see Ronald and Chiu, 2010). In South Korea, for example, public rental housing units have dominated urban housing production since 2002 (see Hyunjeong Lee, this volume). Meanwhile, in a rather different context, after more than two decades of intensive housing privatization, in 2010 the Chinese government announced one of the largest social housing construction programmes in the world with an initial target of around 36 million units by 2015 (see Wang and Shao, this volume). Thus, although there remain significant differences between regions, especially North and South East Asia, a debate has begun about whether a post-developmental state is emerging in some contexts.

Apart from, but related to political changes, the housing pillar of developmental regimes is facing new social, economic as well as demographic, stresses. Among the latter is population ageing, which is threatening to destabilize the balance between working and retired populations that sustained these economies during the high growth era. Changes in families, with increasing numbers of women in paid employment and declining marriage and fertility rates are also reinforcing the ageing trend (Jones, 2007). The undermining of the male-breadwinner model and the family base of welfare is bringing pressure to bear on the state to improve social rights and public welfare provision. Socioeconomic stresses, meanwhile, not only include greater economic volatility and slower growth rates, but also a higher propensity for unemployment that not only affects public resources, but also erodes the capacity of households to sustain stable life-course and owner-occupied housing careers. There have also been political stresses as democratic contestation has deepened in what have traditionally been authoritarian states. In a context of improved aggregate wealth following decades of economic growth, combined with declines in social equality and family welfare capacity, social issues have become central to party manifestos and policy programmes (Hwang, 2011). Housing, which straddles the economic and social, has been central among these.

This chapter has two main objectives. The first is to elaborate the East Asian context and modes of housing, exploring evidence of the existence of a particular model characteristic of the region, and distinct from models characteristic of western advanced economies. This is developed in the first of the two main sections of the chapter. The second objective, developed in the second of the two main sections, is to identify developments that have begun to challenge East Asian housing systems: what we refer to as the seeds of change. While home ownership is still by far the largest single housing tenure and an aspiration that remains undiminished, the severity of economic cycles, demographic trends and ‘new social risks’ have begun to test both the viability and sustainability of established housing and policy frameworks. This chapter thus not only provides a context for understanding housing approaches in the region but also emphasizes the importance of this domain when considering socioeconomic and political changes in East Asia more generally. Furthermore, in a more practical sense, it sets the scene for the country-focused chapters that follow.

Housing and the East Asian model

East Asia has provided a marked contrast to the dominant occidental focused social and economic theories of development. Most countries in the region underwent a rapid industrialization in the second half of the twentieth century and in many cases caught up with – and even surpassed in the cases of Japan and South Korea (hereafter, Korea), both OECD member nations – their developed western counterparts. These countries have not, however, travelled the same routes towards social, technological and economic advancement found elsewhere in the developed world. They have not followed laissez faire free market models of growth, but rather (especially in the early stages) state-planned, bureaucratically coordinated models of strategic development focused on nurturing particular industries and relying on manufacturing and export orientated expansion (see Johnson, 1982). Indeed, ‘developmental states’, as they are often known, represent a brand of economic nationalism within which corporate, political and bureaucratic elites have formed powerful and successful alliances aimed at driving economic growth. At the same time, democratic freedoms and rights of citizenship have been restrained in order to maximize stability and economic productivity. Similarly, the domain of housing has been subject, if not central to, the objectives of development-orientated economies. Before we consider the place of housing, however, it is necessary to explore the specificities of the East Asian region.

The economic context

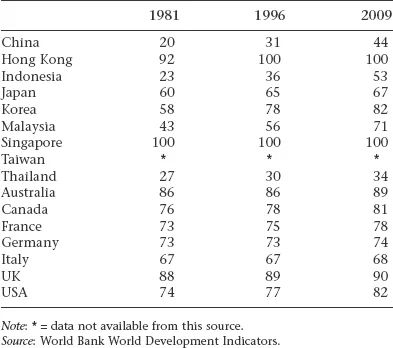

Looking at East Asia in broad terms, a number of similarities in economies and urbanization processes can be laid out. Firstly, with the exception of Japan (an old rather than new developed country1), the speed and relative timing of economic development has been distinctive. This has been seen over the last half century in very high average Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates, far exceeding rates in advanced western economies. It can also be measured by the urbanization rate since urbanization reflects the switch from agricultural-based to manufacturing-based economies (Table 1.1). With the exception of the city-states of Hong Kong and Singapore, which, by definition, are urbanized, the general pattern – contrasting with the longer-established urbanization of western economies – is of urbanization proceeding very rapidly in recent decades, and exerting a continuing and large demand for additional urban housing. Although Korea (at 82 per cent) and Malaysia (71 per cent) have now achieved urbanization rates consistent with those of western countries, it seems likely that strong growth will continue in China, Indonesia and Thailand. In general, the East Asian countries have therefore been characterized by high growth capacities (Wade, 1998).

Table 1.1 Urban population as percentage of total population

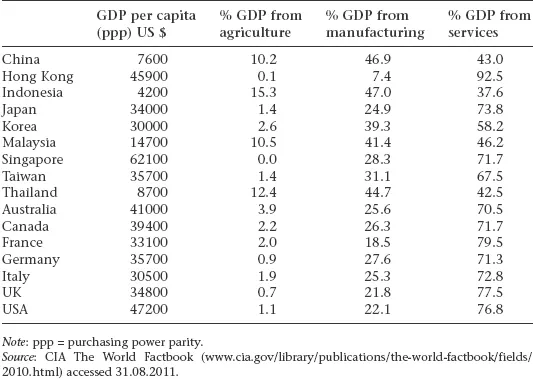

Notwithstanding these commonalities, the East Asian region is diverse and may be considered divided ino a number of parts or regions in terms of social and economic development. First of these are the newest of the newly industrializing societies, or Cub economies (in relation to the more established Tigers). These are generally located in South East Asia, have a lower GDP per capita and a less developed urban framework. In this volume they are represented by Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. In all, their agricultural sectors are still significant, accounting for at least 10 per cent of total GDP, and their manufacturing sectors accounting for between 40 and 50 per cent (Table 1.2). Of this group Malaysia has by far the highest GDP per capita. China in some ways resembles these developmental late starters, but may be considered a class in itself. It is not only larger than the rest of the region put together in terms of area and population, the controlling Communist Party and its reorientation towards market led growth since 1978, has ploughed a very different furrow in terms of accelerated urbanization and economic growth. In 2011 it overtook Japan to become the second largest economy in the world. Meanwhile, economic activities in the rest of the region have become increasingly dependent on the sustained growth of China, which in 2012 achieved a growth rate of around eight per cent of GDP.

Table 1.2 GDP per capita and by sector 2010

Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan, on the other hand, have economies that more closely resemble those of the advanced western countries. Their level of GDP per capita, which is especially high in the case of Singapore, and the balance between agriculture, manufacturing and services place them firmly as post-industrial societies in which service activities predominate (Table 1.2). This is especially the case with Hong Kong and Singapore, both small, city states with little undeveloped land, and agricultural sectors that account for 0.1 per cent or less of GDP. These two countries can also be considered a category apart as they have, for reasons explored throughout this volume, largely managed to resist the democratic transformations that Japan, Korea and Taiwan have undergone in recent years, and have thus been more successful at sustaining lower levels of public welfare spending. Japan, Korea and Taiwan have quite distinct development pathways, but have all achieved very similar levels of GDP per capita. They have increasingly been linked together, not only because of they are well developed, but also because there has been some departure in recent years in terms of social policy transformations (Holliday and Kwon, 2007; Peng and Wong, 2010; Hwang, 2011). There is a level of conformity in these societies in that all have seen changes in government subsequent to the 1997 financial crisis and have consequently endured greater democratic tensions that have shaped approaches to, and support of, developmentalism.

Welfare regimes

Other than being successful, growth-orientated economies that rapidly industrialized in the second half of the twentieth century, what also sets East Asian countries collectively apart is a particular orientation to, and development of, welfare frameworks. Building on the seminal work of Esping-Andersen (1990) a large body of literature has tried to explain differences in the logics of welfare states and comparative differences in social insurance provision. Whereas such studies provided insights into western countries, they have been less successful in explaining the dynamics of welfare provision in industrialized East Asian ones (Abrahamson, 2011). Since the late-1990s, however, a growing number of approaches have attempted to identify a pattern across this group of societies that have, on the one hand, experienced rapid economic growth, while, on the other, supported both constrained expenditure on social welfare and relatively stable political hegemonies.

In response to criticism of his initial categorization of Japan within a western welfare framework, Esping-Andersen (1997) recast developed East Asian societies as hybrids featuring corporate social policies with strong reliance on the market and the family. For Kwon and Holliday (2007), however, East Asia represents a distinct fourth regime type, different from Esping-Andersen’s three western groupings, which are articulated by their productive rather than protective intent. Goodin argues that all welfare regimes are productivist to the extent that they are concerned with ensuring ‘a smooth supply of labour to the productive sectors of the formal economy and they are all anxious that the welfare state not get too badly in the way of that’ (2001, p. 14). For Holliday, the ‘growth at all costs’ strategies that characterized East Asian economies in the late twentieth century resulted in a deeply productivist approach in which social protection measures were subordinated ‘to the overriding policy objective of economic gro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 The Changing Shape of the East Asian Housing Model

- 2 Urban Housing Policy Changes and Challenges in China

- 3 Housing, Crises and Interventions in Hong Kong

- 4 Indonesian Housing Development Amidst Socioeconomic Transformation

- 5 Housing and the Rise and Fall of Japan’s Social Mainstream

- 6 Towards a Housing Policy in Malaysia

- 7 Integrating Economic and Social Policy through the Singapore Housing System

- 8 Housing and Socioeconomic Transformations in South Korea

- 9 The Pro-market Housing System and Demographic Change in Taiwan

- 10 Housing as a Social Welfare Issue in Thailand

- Index