- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

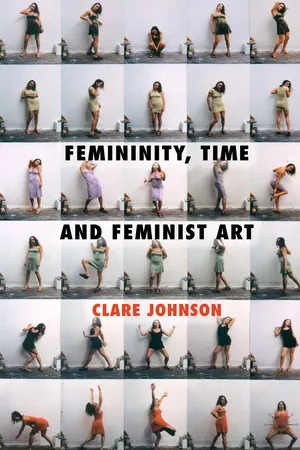

Femininity, Time and Feminist Art

About this book

This book examines feminist art of the 1970s through contemporary art made by women. In a series of readings of artworks by, amongst others, Tracey Emin, Vanessa Beecroft, Hannah Wilke and Carolee Schneemann the reader is taken on a journey through maternal desire, fantasies of escape and failed femininity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Femininity, Time and Feminist Art by C. Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Fantasies of Adventure, Escape and Return: Tracey Emin’s Why I Never Became a Dancer

In this chapter I analyse Tracey Emin’s short film Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995) and argue for its importance to a feminist art history that takes time as its principal concept. My intention is to explore how Emin’s feminism is articulated through the manipulation of time and to consider how her work has been critically positioned in relation to feminist art of the 1970s and 1980s. By starting this book with an analysis of a film by Emin I wish to signal that my approach is not chronological. It does not follow a developmental path of precedents and influences that lead up to Emin’s work, but takes her provocative expressions of desire, trauma and memory as a starting point for feminist art history. It is to start where students of visual culture often begin their journey into sexual politics, with a visual practice that speaks to them about something that matters.

In Why I Never Became a Dancer Emin reflects on the experience of being humiliated at a dancing competition in the late 1970s from the position of her adult self in the 1990s. The film is a useful entry point to the central theme of this book because it explores and plays with the differences between the 1970s and 1990s including the different cultural, social and sexual contexts in which humiliations are experienced. There are in fact three different time periods at play in the analysis that follows: memories of the late 1970s in which the story is set, the context of the film’s production in the mid-1990s, and the present day of my encounter with it. The triangulation of these time periods enables a fresh analysis of the connections and tensions between female sexuality, femininity and feminist politics. The visualization of memory and ability to imagine a better future free of humiliation connect temporality to sexual politics in the narrative of Why I Never Became a Dancer. Emin made this film at a time when post-feminist representations of women were becoming increasingly widespread. The idea of post, meaning ‘after’, feminism has met with a fierce response from feminist critics and this provides the main critical framework for the chapter. Post-feminism is itself an aggressively temporal idea, which suggests the desire to move on from a rights movement erroneously consigned to the past. In the context of this rhetorical and contextual notion of a past tense of feminism, I focus on two specific temporal strategies within the film through which the relationship between Emin’s femininity and feminism is articulated: the renegotiation of meanings across time and the narrative of escape from the past.

Fragile conservatism

To write about Emin over ten years into the new millennium presents both opportunities and challenges. There is now a plethora of material by and about the artist, which provides a rich resource to work with. Through a combination of major exhibitions, numerous appearances on television and radio, contributions to newspapers and celebrity connections Emin’s position as a doyenne of the contemporary British art scene is secured. On the other hand, the artist’s acceptance of this position is a far cry from her earlier days spent challenging the expectations and attitudes of the art establishment. One such venture was her collaboration with Sarah Lucas with whom she opened The Shop on Bethnal Green Road in London in 1993. The artists sold a variety of handmade items in The Shop, which existed outside the institutional limitations of the artworld and commented playfully on its system of reverence for celebrated artists. Examples included Damien Hirst ashtrays and Mark Rothko comfort blankets. Four years later Emin famously appeared drunk on television during a live Channel 4 discussion show after the awarding of the Turner Prize in 1997. It was an irreverent display of dis-identification from the artworld, which introduced Emin to the wider public as either a refreshing antidote to artworld pomposity or an embarrassing interloper without the required level of seriousness and self-control. She was, however, brought back into the fold when two years later she was shortlisted for the Turner Prize with her installation My Bed (1998). In 2007, a decade after her infamous appearance on TV, Emin was made a Royal Academician and awarded honorary doctorates from the University of Kent, London Metropolitan University and the Royal College of Art where she is now Professor of Drawing. By the time her 2011 survey exhibition ‘Love Is What You Want’ opened at the Hayward Gallery in London, she had publicly supported the British Conservative party in the 2010 general election and in an interview with John Humphries on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme acknowledged without regret that she is now part of the art establishment (16 May 2011). Talking to British TV and radio presenter Andrew Marr in May 2012 Emin claimed that the establishment is now based on meritocracy rather than class (Andrew Marr Show, BBC1).

This move from margin to centre presents a challenge to those, myself included, who want to argue for the feminist, progressive potential of Emin’s practice. Feminist art has articulated the material, sexual and cultural inequities that women face with a view to developing radical, subversive and oppositional strategies. So, how can feminist art historians and critics endorse an artist who has embraced the establishment and whose own politics are at odds with the trajectory of left-wing thought that informs dominant narratives of feminist art? One answer lies in Emin’s uneven and contradictory relationship to the art establishment. In 2008, for example, she took up the invitation of a retrospective at the Scottish Gallery of Modern Art yet retained a resistant and playful approach to this most conservative of cultural forms. The retrospective is an active form of remembering, which simultaneously produces and celebrates an artist’s legacy. However, the tradition of the retrospective and the memory-work of Emin’s oeuvre are differently gendered. Whereas the retrospective is an art historical form used to secure the dominance of patrilineal control and influence emanating from a celebrated individual, Emin’s mediated memories of pain, pleasure, disappointment, humiliation and trauma construct a sense of fragility that beckons the experiences of the women who are drawn to the work. It is as though Emin relishes the opportunity to have the legitimation of a retrospective bestowed upon her so that she can play with the narration of gendered memory (sexual and artistic) that her work has always focused on. If Emin appears to occupy the centre ground she cannot resist the temptation to test its boundaries. It is one of this book’s arguments that in an understandable rush to avoid appearing to drift to the right art critics and historians are in danger of missing the critical nuances of artworks produced by commercially successful artists, whose political affiliations may not chime with their own. In Emin’s case the critical potential of her art is connected to her manipulation of time in the forms of memory, futurity and endurance. These concepts find some of their most powerful expressions in her short films.

The renegotiation of meanings over time

Shot on Super 8 and running at just under seven minutes, Why I Never Became a Dancer features Emin narrating the story of her own adolescent experiences as a young teenager growing up in Margate in the late 1970s. It has been described as a video-poem, which captures something of its affective rhythm and intensity of feeling (Smith, 2011, p. 29). The imagery in the early part of the film is faded and amateur, which gives it a nostalgic tone. Emin’s voice is heard over footage of a seaside town and describes her early experiences of under-age sex against the backdrop of a rundown landscape.

Sex was something simple

You’d go to a pub – walk home

Have fish and chips – then sex

On the beach

Down alleys

You’d go to a pub – walk home

Have fish and chips – then sex

On the beach

Down alleys

Sex is initially described as an empowering adventure, something that made her feel free and alive. Emin then describes her love of dancing and how this replaced sex as a form of bodily pleasure:

I stopped shagging

But I was still flesh

And I thought with my body

But now it was different

It was me and dancing

(Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer, 1995)

But I was still flesh

And I thought with my body

But now it was different

It was me and dancing

(Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer, 1995)

The story becomes increasingly disturbing as Emin explains her participation in a disco dancing competition. During her performance she is taunted by men with whom she has had casual sex, who chant ‘slag’ until she runs off the dance floor knowing that she has lost the competition, vowing to leave Margate for a better life. I read it as a story about the desire to access a different sexual and material economy, which is represented by the possibility of success at the disco dancing competition. The final part of the film shows Emin as an adult woman, smiling and dancing to Sylvester’s disco hit You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) (see figure 1.1). She recites the names of the offending men and tells them that ‘this one’s for you’ in a gesture of defiance and embodied pleasure. In a triumphant riposte she demonstrates that as an adult she is still ‘thinking with her body’ and enjoying it. Here the camera is positioned as if it is held by someone dancing with her, circling in a way that visually connects this scene to the continual camera movement and visual restlessness that characterizes the earlier part of the film. We are invited to share in her sense of embodied empowerment as she articulates the political charge of her personal story.

Figure 1.1 Tracey Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995), single-channel projection with sound, shot on Super 8, 6 minutes, 30 seconds

Source: © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2013.

Source: © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2013.

It is significant that Emin does not offer us a visual image of the power relations inscribed on to her body in the original dancing competition. She reserves this for her moment of glory when, for the first time, we see her dance. Emin’s level of control over her visual availability is in stark contrast to the story of her former sexual availability. Her adult self tightly controls the representation of the younger Emin as playing truant from school, having sex in public places and living a life outside institutional control. By withholding and then allowing our gaze Emin turns the sexual economy, through which the insults that she recounts have meaning, into an affective economy, which opens up a range of feelings and alignments with the film: guilt, shame, pleasure, empowerment, depending upon where you position yourself in relation to the narrative. This is enabled by Emin’s renegotiation of the meaning that Sylvester’s track represents for her over time.

You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) was released in 1978, which is the same year as the dancing competition referred to in the film, thus enabling a recreation of the scene through Emin’s adult eyes. The irony of the scenario in 1970s Margate is that You Make Me Feel was interpreted by some as a gay anthem, accompanied by a video in which Sylvester appeared in full drag. The emergence of a widespread gay culture in the intervening years offers the adult Emin an opportunity to make a subtle mockery of the aggressive masculinity that jeered her off stage as a teenager. The mainstreaming of disco opened up audiences within both the gay and straight communities who have appropriated its meanings. For Emin, dancing to Sylvester’s track in the mid-1990s puts into effect a set of meanings quite different from those she experienced at the competition in the late 1970s. Part of her triumph is in successfully enacting the discrepancy between the classed and gendered meanings that disco music represents across this period of time, such that the dance floor becomes a site of initially failed and then achieved femininity. In 1978 she was positioned by those who taunted her as sexually available, undisciplined, vulgar and in excess of the restraint required of feminine conduct. Her lack of respectability can be understood through Beverly Skeggs’ work on class and gender (Skeggs, 1997). In her influential ethnographic study of white working-class women in the North-West of England, Skeggs raised awareness of the significance of respectability as a signifier of class. Noting that it is primarily an issue for those deemed not to have it, Skeggs identifies the aspirational aspect of middle-class respectability on the part of those positioned as tainted, pathological and without boundaries or control. However, as an artist working in the mid-1990s Emin exerts a great deal of control over her image and enjoys the benefits of more recently acquired cultural capital. She appears at ease with herself and confident in her work. There is a long history of judgements about female respectability being articulated within the visual image, both within art history and popular culture. In Why I Never Became a Dancer Emin takes hold of this and reworks her earlier subjection to moral judgement.

By providing an authorial voiceover to images of a past that is both romanticized and troubling Emin interweaves her experience of late-1970s Margate with her political consciousness in the mid-1990s. The overlaying of imagery from one period of time with a voiceover from another suggests an overlapping approach to memory, working across and between two historical moments. However, sound and image are treated differently in relation to time. Emin’s voiceover is certain and suggests no fading of memory or doubt in the story. She recalls the names of the men and exactly how they made her feel. This contrasts with the fragility of the imagery, which is impressionistic rather than definite. In her choice of film stock Emin signals the subjective nature of memory as a series of stories that are always told from a point of view. The grainy character of super 8 footage calls attention to its existence as mediated image rather than transparent truth because it makes no attempt to hide its filmic quality.

Ambivalence and the post-feminist subject

In arguing for the feminist provocation of Emin’s art my account differs from some other interpretations of her work. Like many other artworks discussed in this book, Emin’s practice has not been universally accepted into feminist art history. Cultural theorist Angela McRobbie argues that Emin’s work demonstrates an ambivalence and disavowal towards feminism as that which must not be named (2009, p. 121). For McRobbie, who is working in a UK context, this is symptomatic of a post-feminist media culture in which feminism is strategically dismantled. During the period in which Emin made Why I Never Became a Dancer post-feminist representations of femininity were becoming increasingly common. Post-feminism is a contested term and as others have pointed out has been used in a number of ways by different authors (Projansky, 2007; Jones, 2003). Most frequently, however, it gives name to a tendency that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s to represent feminism as homogeneous, unattractive and irrelevant to contemporary life. It suggests a time after feminism, which is left behind as if it is unnecessary. As a concept it is blind to the diverse range of experiences of gender-based oppression, assuming a universal feminism that has achieved its aims.

Post-feminist representations of women often include a playful dis-identification with a strict and humourless feminism. Judith Williamson has observed this tendency in adverts that use a parody of sexualized femininity to delineate contemporary attitudes towards female sexuality. Writing in 2003 Williamson noted that the concept of sexism had fallen out of use in public discussion. Through her analysis of contemporary editorial advertising, she argued that the notion of sexism is often employed as a nostalgic stylistic signifier rather than a form of political critique. Through a visual language of pastiche and retro styling there is a reference to a former moment of sexism, which is often visually located in the 1970s. Examples of this tendency include a 2002 Alfa Romeo advert featuring a leggy model that, as Williamson observes, is reminiscent of TV dance troupe Pan’s People. Sexism is placed in quotation marks and framed within a sense of nostalgia for a time when it was innocent, a time before feminism had imposed political correctness and ruined the fun (Williamson, 2003, pp. 44–53). Any sense of the politics of the women’s movement is lost in the way in which these adverts invoke sexism as nostalgic innocence. The implication that Williamson objects to is that sexism belongs in the past, which makes it difficult to challenge. To do so would be out of step with the cool irony that was arguably favoured within the advertising industry at this time, as if to claim sexism in the present is to misunderstand the spirit of the times and reveal an absence of graphic design sensibility.

Many other feminist authors have challenged post-feminist formulations of womanhood often by critiquing conservative representations of femininity in advertising, journalism, popular film and TV. Diane Negra, for example, provides a brilliant analysis of the central position given to the American post-feminist subject as, amongst other female types, chick-flick heroine, stay-at-home mom, and self-care specialist (Negra, 2009). Much of this literature reflects on media representations of choice. In a distortion of hard fought for gains this focuses on the choice to reject feminism as if it is something to be liberated from. Amelia Jones has identified an anti-feminist voice in American sexual politics and illuminates this through an examination of the use of photography in news media and advertising (Jones, 2003). For Jones the increasing visibility of gay, feminist and non-white identities is a cause of anxiety to white, anglo hegemonic masculinity, which uses conservative post-feminist imagery to shore up its authority. There is now a wide body of literature in this field and a series of concerns that stretch across the interpretation of different media forms, from the narratives they tell to the (audio) visual languages used to naturalize their values. By working across a range of media forms Jones, McRobbie and Negra signal the pervasiveness of post-feminist ideology on both sides of the Atlantic. This ideology includes a reactionary approach to gender politics and the invocation of a fantasy feminist as a figure of hate. This anonymous, generic feminist is hostile to family life, overly serious and aggressively ambitious. She has burdened women with too many life choices and is to blame for the conflict between work and family life, which is understood as a personal problem for women who struggle to ‘have it all’ rather than a socio-political issue requiring structural changes such as flexible working hours and affordable childcare. In the place of the monstrous feminist enters an imagined post-feminist ideal who is white, hyper-feminine, Western, affluent, upper-middle-class, heterosexual and young (often referred to as a girl rather than woman). The new feminine ideal is educated up to a point, but ultimately rejects professional and public life in favour of heterosexual matrimonial duties. She is a proficient consumer and prefers materialist forms of femininity to social critique, which she finds distasteful and unfeminine. Her sense of empowerment is derived from consumption, which necessarily excludes many women for whom access to commodity culture is hopelessly out of reach. What makes post-feminist rhetoric so malevolent is the extent to which it constructs its values as common sense, for example the desire to look forever young or to reign in ambition. The post-feminist subject is as much of a caricature as the feminist she replaces, but powerful nonetheless.

In the UK and US post-feminist representations emerged during a time of economic prosperity for the group it privileges, but in a climate of financial hardship, rising unemployment, unfavourable policies for women and disincentives to pursue higher education the inequalities of post-feminist rhetoric are thrown into sharp relief. No longer so young and with employment prospects increasingly fragile, the affirmative, youthful consumer of post-feminist representation is under threat. Fear for the future encourages a reconsideration of the sexual politics of the recent past. So there are multiple layers of time at play. First, the concept of post-feminism is itself entrenched in a never-ending aspiration to youthful femininity that lies out of reach in an imagined future, whilst simultaneously invoking nostalgia for an earlier moment of pre-feminist identification with femininity. Second, there is the vantage point of the present day from which these temporal contradictions can be viewed.

While much has been written about post-feminism from the point of view of feminist cultural studies, it is less frequently used as a critical vocabulary within art criticism, despite the permeable boundary between art and popular culture that characterizes the work of Emin and many of her contemporaries. Mc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Fantasies of Adventure, Escape and Return: Tracey Emin’s Why I Never Became a Dancer

- 2 Traces of Feminist Art: Temporal Complexity in the Work of Eleanor Antin and Elizabeth Manchester

- 3 Sexuality, Loss and Maternal Desire in the Work of Carolee Schneemann and Tracey Emin

- 4 Feminist Narratives and Unfaithful Repetition: Hannah Wilke’s Starification Object Series

- 5 Critical Mimesis: Hannah Wilke’s Double Address

- 6 Smooth Surfaces and Flattened Fantasies: Thoughts on Criticality in Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Soliloquy III

- 7 Near-Stillness in the Art Films of Sam Taylor-Johnson and Vanessa Beecroft

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index