eBook - ePub

The Cultural and Political Intersection of Fair Trade and Justice

Managing a Global Industry

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Cultural and Political Intersection of Fair Trade and Justice

Managing a Global Industry

About this book

The Cultural and Political Intersection of Fair Trade and Justice is an ethnographic study of the effects of Fair Trade on indigenous women, as reported by the women themselves, and seeks to develop a deeper understanding of Fair Trade, globalization, culture, and policy in building justice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cultural and Political Intersection of Fair Trade and Justice by Tamara L. Stenn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

BUILDING CONTEXT

This section presents a macro view to Fair Trade and builds the platform upon which one can examine the idea of fairer trade and justice. It creates language, context, and breaks down complex issues of trade into that of four pillars: government, producers, consumers, and institutions, enabling trade to be understood from multiple perspectives. These multiple perspectives are analyzed and supported by Amartya Sen’s ideas of justice as readers are presented with new ways of viewing and understanding situations. Fair Trade is a global phenomenon taking place across nations and housed in governments, institutions, and our hearts. Part I gives us the tools and perspective to more deeply understand it.

1

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO FAIR TRADE AND JUSTICE

FAIR TRADE OVERVIEW

Fair Trade is a form of commerce started post–World War II in the 1940s by American and European organizations as a way to provide relief to war refugees and marginalized people through the sale of handicraft items made by those populations (Shaw, Hogg, Wilson, Shui, & Hassan, 2006). By teaching people to create handicrafts that sold in the United States and Europe, income was generated to help the struggling populations. Over time, Fair Trade evolved to include food items, embrace cultural diversity, gender, environmental sustainability, long-term development, and brought greater economic return to a million small-scale producers across the globe (Warrier, 2011). Fair Trade is now a $6.8 billion industry (WFTO, 2012). It is most visible in the coffee and chocolate industries though it also includes flowers, sugar, quinoa, rice, bananas, grapes, gold, tea, herbs, rice, honey, nuts, cotton, vanilla, wine, clothing, sports balls, wood, potatoes, and handicrafts (Fairtrade Labeling Organizations International [FLO], 2011). Fair Trade products largely originate from poorer countries and are sold, often at premium prices, to consumers in richer countries.

The early model of helping impoverished people via the development and sale of consumer goods slowly caught on. In 1958, Milton Friedman wrote of the importance of the United States adopting a foreign economic aid program of skills development as a way for “uncommitted nations” to build economic growth by engaging in the US’s free market democratic ideologies. “If we do not help them,” warned Friedman, “they will turn to Russia” (Friedman, 1958, p. 1). US national interest coincided with its humanistic ideals, explained Friedman. “Our fundamental objective,” he wrote, “is a world in which free men can peaceably use their capacities, capabilities and resources as effectively as possible to satisfy their aspirations” (1958, p. 2).

“Trade not aid,” became the call in international development in the 1980s, as producers supported by liberal advocates voiced a preference for dignity by earning returns from the sale of goods, rather than passively receiving donations. Instead of sending money, neoliberal development policies focused on measures that enabled the developing world to trade its way out of poverty. “Give a man a fish; you have fed him for today. Teach a man to fish; and you have fed him for a lifetime” was the mantra of that time. Many development projects began focusing on skills building and microenterprise development with a goal of export production (Yusuf & Stiglitz, 2001). This model played out in the 1990s with the advent of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and a shift toward more liberalized trade, or neoliberal globalization, with a focus on promoting “self-regulating” free markets to create a better world (Steger & Roy, 2010).

Critics challenged the assumption that the developing world could independently export its way out of poverty. Neoliberal globalization increased global competition, shifted production to less expensive regions, and grew global inequality (Urata, 2002). Inexpensive goods created in the developing world, with lower production costs, posed threats as they competed with the now more expensive, locally produced goods. This led to local industry failure and local job loss. Neoliberalism led to a rise in inequality, and the exploitation of workers and the environment as unfettered free market competition drove producers to reduce costs to the detriment of workers who received low, or no, salaries and the environment, which was left unprotected (Stiglitz & Charlton, 2005). In addition, neoliberal globalization produced social hierarchy through its unequal domination by a group of upper classes or advanced countries.

The institutional Fair Trade studied here is not a development project nor is it neoliberal globalization. It functions independently in the free market, with producer groups volunteering to adhere to Fair Trade guidelines in exchange for specialized export market access. Fair Trade principles, which vary among the handful of Fair Trade institutions, create market restrictions that fly in the face of free trade policies. Fair Trade markets are not “self-regulating” or free but rather highly restricted by imposed guidelines that demand a certain level of wages be paid to producers, environmental protection, cultural preservation, and financial responsibility for the well-being of the community.

Some Fair Trade adheres to minimum price guarantees. This type of pricing principles was first introduced by Keynes in his postwar economic order plans at the turn of the twentieth century. “Proper economic prices should be fixed not at the lowest possible level, but at the level sufficient to provide producers with proper nutritional and other standards in the conditions in which they live . . . and it is in the interests of all producers alike that the price of a commodity should not be depressed beyond that level, and consumers are not entitled to expect that it should” (Keynes, 1921, p. 212). The current Fair Trade model developed independent of Keynes’s ideas though; it is interesting that he had the foresight to consider the importance of such principles in a capitalist structure.

Fair Trade has a strong social aspect that does not exist in the neoliberal trade arena in which it functions. Neoliberal trade proponents believe that social needs are met through the “trickle down” effect of free trade. For example, the gains from the sale of a product are naturally distributed through taxes, wages, and other means. Revenue automatically “trickles down” through the economy meeting people’s social needs, like rainwater through soil. The belief is that there is no need for the government or institutions to get involved to regulate social benefits; they are a natural outcome of trade. Fair Trade is different. It demands that tangible social benefits be a core part of the trade model, reflected in the cost of the goods, and communicated to consumers. Often the countries where Fair Trade operates do not have the infrastructure to capture the trickle-down effect, have low wages, and no local tax structure or social programs (Figure 1.1). Most certified Fair Trade agricultural products have a “community investment fund” where a percentage of sales is set aside for community projects such as building schools, roads, and improving community infrastructure; this enables Fair Trade to provide the services that local governments cannot. Fair Trade is not free trade, as some mistakenly believe; it is in fact, highly restrictive.

Ironically, many of the “trade not aid” development programs with a focus on skills building and microenterprise development were not successful in producing viable export businesses in the highly competitive neoliberal global market, as was the intent of the programs, but instead laid the foundation for future Fair Trade work. Producers trained in microenterprise development often had no market access, tools, or knowledge. Many were illiterate, and located in rural or remote areas, with limited resources, and scant communications (Eversole, 2006). The assumption was that the quality of the production itself would be enough to “sell” the product to foreign markets regardless of producers’ vast market barriers such as foreign language and competition. Sometimes microenterprise development projects included sales to foreign markets, though they usually lacked long-term market development or commitment. Sales were often dependent on an English-speaking foreign worker being present to negotiate them. Once the foreign worker left, these sales ceased (Eversole, 2006). Producers simply did not have the resources, skills, or language to pursue access to foreign markets on their own. Products created for export were often too expensive for in-country consumers, or did not appeal to local markets. Nevertheless, producers had viable products and a tremendous opportunity to sell them if a link could be made between the producer and foreign markets. This is where Fair Trade enters.

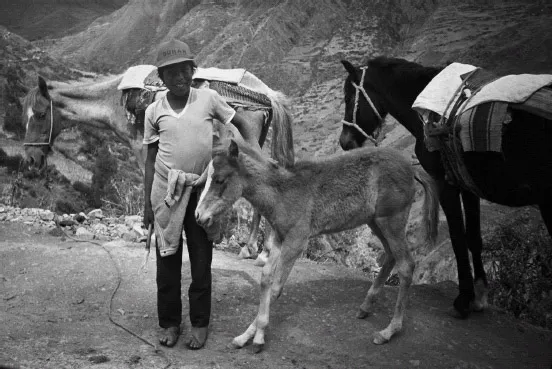

Figure 1.1 Goods are transported by horse and donkey on Bolivia’s dirt paths. A lack of infrastructure and challenging mountainous terrain make moving goods to market difficult. (Photo: N. Trent, 1998).

Often it was a foreign anthropologist doing research, the spouse of a foreign worker, or a development worker engaged in other projects in the area who would “discover” these trained producer groups, recognize the market opportunity, and develop their own enterprise to export and distribute these goods. A recent Fair Trade Federation (FTF) member survey found that of the long-term members (more than ten years), one-third met the Fair Trade producers they worked with while visiting the country as a tourist or guest and another one-third were actually from the region where the production took place (Stenn, 2012b). I personally have worked in Fair Trade since 1996 when, as a US Peace Corps volunteer, I recognized the market potential for Bolivia’s hand knit alpaca sweaters and founded KUSIKUY Clothing Company, a small US-based Fair Trade knitting company with membership in the FTF and production in Bolivia. Being familiar with the producers in their cultural context, emerging fair traders worked in a culturally sensitive manner, forming long-term relationships with producers, and embracing producers’ values of community and the environment, the same values embraced by Fair Trade’s institutions. The main motivation for the FTF members to identify with Fair Trade was that it fit their personal values. More than half of them also enjoyed helping others (Stenn, 2012b). Once a connection was made with a producer group, in country, Fair Trade’s imposed, restrictive guidelines were a natural fit. However, for those not familiar with the producers, their place of origin, culture, language, and traditions, Fair Trade principles were daunting and inaccessible. Fair Trade institutions were formed to help bridge this gap between Fair Trade production and Fair Trade distribution and consumption. Today thousands of world shops, retail outlets, and private companies participate in Fair Trade by maintaining memberships with institutions (WFTO, 2012). This enables members without a direct producer connection to still support and participate in Fair Trade, making it more accessible to all.

Largely viewed as a way of bringing social justice to the world’s most impoverished, Fair Trade is a tool for creating economic justice and building freedom though cooperation and solidarity between producers and buyers. Fair Trade is supported by producers who voluntarily embrace its guidelines by working together, sharing resources, improving product quality, and providing transparency in their daily business operations (Figure 1.2). It is also supported by buyers who respect the producer relationship and promote the Fair Trade guidelines to ethically motivated consumers, retailers, and distributors. As a result, Fair Trade producers and buyers form strong, long-term relationships enabling producers to gain access to secure, lucrative export markets (Hayes, 2006).

Besides the producer-buyer relationship, Fair Trade is supported by consumers who purchase Fair Trade products for several different reasons. Some see Fair Trade as a way to support the ethical treatment of workers and the environment, others enjoy the uniqueness and quality of the products, while still others identify with being part of an eco-ethical movement and view their Fair Trade purchases as a norm within that movement (Ekici & Peterson, 2009). Eco-ethical consumption values include “solidarity, multiculturalism, respect for human rights and ecology” (Llopis Goig, 2007, p. 469).

Figure 1.2 A Bolivian producer creates hand knit sweaters for KUSIKUY, a US-based Fair Trade clothing company. (Photo: T. Stenn, 2008).

When examining the different pillars of Fair Trade, one can refer to the parable of the blind men and the elephant. In this ancient fable, it is told that four blind men encountered an elephant. One grabbed its leg, concluding that it was a tree trunk. One held the tail thinking it was a whip. Another touched the elephant’s trunk and decided it was a hose. The fourth man patted the elephant’s side concluding it was a wall. The wise, sighted man then told them, “All of you are right.” This parable is applicable to the idea of Fair Trade as well. Fair Trade changes depending on which pillar it is being viewed from and what the viewer’s own perceptions are. Depending on one’s position and personal experience, the definition and understanding of Fair Trade shifts. Like the blind men, “all are right” but they are different. Viewing these differences from the constant of Sen’s ideas of justice creates a broad, multifaceted way in which to understand our elephant, the cultural and political intersection of Fair Trade and justice.

Justice is a global concept. The English language does not allow a large enough vocabulary for the full examination of it. Sen, who is of Indian descent, uses Sanskrit vocabulary to help distinguish two significantly different ways of defining justice that enables a greater conversation about Fair Trade and justice to be realized. Nyaya, is Sanskrit word for a, “comprehensive concept of realized justice” (Sen, 2009, p. 20). While niti, is Sanskrit word for a more concrete, tangible, and narrowly applied, justice, often in the form of rules, laws, and “organizational propriety and behavioral correctness” (Sen, 2009, p. 20). The niti concept of justice is familiar to the Western thinker and refers to norms, standards, and regulations. A niti view of Fair Trade justice focuses on its guidelines, compliance, and certifications. However, it is within the complexities and expansiveness of nyaya where a larger, transformational understanding of justice lies. Looking at Fair Trade justice with nyaya means understanding peoples’ lives and how trade mixes through them. It includes the lives of business owners and consumers, institutional directors, political leaders, and producers; everyone touched by trade. A nyaya view of Fair Trade justice focuses on broad, interconnected, complex relationships.

The nyaya view of justice is often counterintuitive to Western thinkers who are used to being linear and precise in their understanding of things. Neve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Building Context

- Part II A Fair Trade Case Study: Bolivia, South America

- Part III The Women of Fair Trade

- Part IV Putting It All Together

- References

- Index