eBook - ePub

The Renminbi Rises

Myths, Hypes and Realities of RMB Internationalisation and Reforms in the Post-Crisis World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Renminbi Rises

Myths, Hypes and Realities of RMB Internationalisation and Reforms in the Post-Crisis World

About this book

This book breaks new ground in research on the RMB's offshore market by addressing the myths, hypes and realities surrounding the rise of the Chinese Yuan. It is the first book to address the rise of the Renminbi by focusing on the structural factors behind it and drawing on the global, regional and domestic developments affecting its development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Renminbi Rises by C. Lo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Corporate Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Renminbi Shakes Up Global Currencies

For more than a decade, when the foreign exchange market has talked about the three major global currencies, or the “G3,” it has been referring to the US dollar (USD), the Euro (euro) and the Japanese yen (JPY). These three currencies account for over 70% of all foreign exchange (FX) transactions in recent years. However, there are seismic structural shifts unfolding behind the G3 and the emerging markets, giving rise to some distinctive trends that are conducive to the rise of the Chinese renminbi (RMB),1 or the “redback,” as market players sometimes call it, to challenge the global dominance of the G3 currencies.

The unfolding structural trends behind the G3 currencies are 1) the weakening of the USD’s global influence, 2) the uncertainty of the euro and 3) the structural decline of the JPY on the global stage. Meanwhile, even with a closed capital account, the economic, financial and political influences of China and the RMB on global markets have increased substantially. The world should seriously think about adding the RMB to the global currency trio, and redefine the group as the “G4” – USD, euro, JPY and RMB. RMB internationalisation seems to be an inevitable development in the global markets.

These structural changes are part of a larger evolution in the global macro landscape that is shifting the weight towards emerging markets (EM) and away from developed markets (DM). While the world is watching the rise of the RMB, the financial market has developed the expectation that Beijing might be freeing the currency soon to meet its currency internationalisation objective, breaking its long-held obsession with exchange rate control. Such an expectation turned euphoric in late 2011 when the RMB was allowed to appreciate against the USD by almost 1% in just a week. The sudden appreciation happened again in October 2012, just a few weeks before the US presidential election, when the redback was allowed to rise by over 2% against the USD within two weeks.

Despite the RMB’s sudden moves, such expectations are wrong, in my view, because Beijing’s FX policy is closely tied to its export policy. China’s export policy is indeed a social policy for maintaining systemic stability. A sluggish RMB policy with limited trading flexibility is instrumental for achieving that goal. As long as such a fundamental backdrop to the RMB policy is not changed, Beijing is unlikely to make any significant shift in its FX policy, despite its intention to internationalise the yuan. So contrary to the market’s euphoria about freeing RMB trading soon to help speed up the RMB internationalisation process, we should expect a change in the RMB regime to proceed slowly.

Structural change drivers

What moves the currency markets and shifts the relative importance of the currencies boils down to the long-term valuation of the currencies and shifts in countries’ balance of payments (BoP). Let us review these forces and see how they change the underlying structures of the G3 currencies and create a constructive environment for the rise of the RMB.

Valuation

One of the crucial rules governing FX markets is that if a currency is not overly manipulated by policymakers, it should revert back to some mean, or fair value, over time. Some economists see this fair value in terms of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP),2 which was popularised by the Economist magazine’s Big Mac Index (The Economist 2012). Such longer-term FX mean reversion has solid economic logic behind it.

When a currency appreciates to a certain point for a sustained period of time, its host country’s exports will lose competitiveness. Ceteris paribus, sustained currency appreciation becomes a drag on growth. Meanwhile, the stronger currency helps curb the country’s inflation. The change in the outlook towards slower growth and lower inflation tends to create investor expectations of monetary loosening by the central bank, thus reducing the expected yield on the currency. The change in expectations and actual growth-inflation dynamics often leads investors to cut exposure to assets denominated in that currency. This, in turn, cuts demand for the currency and generates FX depreciation that eventually move the currency back to its fair value. The story goes in the opposite direction for a currency that has experienced sustained depreciation.

While some argue that these cycles often average five to seven years, empirical evidence also shows that the mean-reversion process could occur more quickly than that, especially when over- or undershooting of the currency against its fair value becomes extreme. However, a currency’s fair value is not fixed over time. Structural changes in underlying economies, which affect macro variables such as terms of trade (ToT), inflation and interest rates, can increase or decrease a currency’s fair value. Macroeconomic development in recent years suggests that such a shift may be happening today for some currencies, with a bias towards higher fair values for certain commodity currencies and emerging market (EM) currencies, and a lower fair value for the USD.

Balance of payments

While valuation helps one to understand whether a currency is under- or overvalued in a longer-term context and, hence, its influence on the global markets, balance of payments flows (BoP, or cross-border trade and capital flows) help determine the demand for the underlying currency in the shorter- and medium term. Until the late 1990s, when portfolio flows became a significant FX driving force, cross-border trade flows were the key driver of currency movement and the relative weight of the currency (in terms for its importance) in the global markets. A country like the United States with a chronic current account deficit would sell USD to buy foreign currency for purchasing imports. Ceteris paribus, such flows weighed on the dollar, especially relative to currencies where the respective country ran a current account surplus.

However, recent years have seen a shift in BoP flows. While trade still matters, global capital flows have become the dominant factor driving the currency markets. A reduction in regulatory hurdles and greater availability of information (including media coverage of global markets and economies, and the Internet) have made many investors more willing to look overseas for asset and risk diversification. This, in turn, complicates the currency demand and supply dynamics. Hence, one needs to know what drives cross-border capital flows in order to gauge the rise and fall of a currency both in terms of its value and its weight of global importance.

With these issues in perspective, let us look at the structural changes underlying the G3 currencies to see how they give rise to an international backdrop that is conducive to the rise of the redback in challenging the global dominance of the G3 currencies, especially the greenback (USD).

USD dominance weakening

The USD is in a league of its own in the FX markets. Its dominance in the global system will remain for many years to come, but the degree of this dominance will weaken gradually. The US economy is by far the largest in the world, accounting for almost 30% of global GDP in 2009. The USD, meanwhile, continues to be the most traded currency in the world FX markets, accounting for 45% of all currency transactions in 2010. This “critical mass” in the global market is part of what creates the dollar’s “reserve currency” status. Given the significant amount of global trade and financial transactions done with the United States, central banks around the world try to hold a correspondingly large amount of US securities (typically Treasury bonds) in their reserves as a need for external settlement and a protection against BoP shocks.

This reserve currency status and the size and composition of the US economy and capital markets have made the dollar unique. Consider trade flows within the BoP. The United States is a country of consumers, with private consumption accounting for some 70% of GDP. When US growth is robust, Americans spend more and buy more from overseas. This is manifested in the chronic US current account deficit, which has lasted 31 out of the past 39 years. But this is also a natural way to internationalise the USD, as a current account deficit means more dollars are sent overseas to pay for imports than are received from US exports. These offshore dollars, in turn, have created deep and diversified offshore FX and dollar asset markets. All else equal, the chronic current account deficit should be a drag on the dollar’s value.

That said, as noted earlier, currency trends reflect capital as well as trade flows. Here the dollar story gets more complicated. Historically, the US investor base has exhibited a strong home bias – i.e. American investors have tended to be heavily focused on investing in US assets. This bias has faded somewhat in the last two decades, thanks to market globalisation. Today when the US economy is doing well, Americans put relatively more money to work overseas. This exacerbates the dollar drag from the widening trade deficit, leaving the dollar weaker during growth periods and stronger during economic slowdown.

In an economic slowdown, the trade deficit shrinks and capital is repatriated back to the United States, providing a support for the dollar exchange rate. Data going back to the early 1970s show that annual percentage changes in US real GDP and changes in the trade-weighted dollar exchange rate have a negative correlation of 0.24. In other words, for almost 25% of the time, good US growth has been bad news for the dollar exchange rate, and vice versa.

In addition to its chronic current account deficit, America’s huge debt burden (US household debt is over 100% of disposable income, while its public debt is approaching 100% of GDP at the time of writing) should also be instrumental for keeping the USD weak for a prolonged period. This is because low interest rates are needed to prevent a debt blowout that would derail the economy from its sustainable path. Low interest rates certainly weigh on the dollar, as they encourage investors to look outside dollar-denominated assets for higher returns. If unresolved, the huge US debt problem will also erode international confidence in US sustainable growth and hurt demand for US assets, including the USD.

Meanwhile, structural changes are taking place in many emerging economies, including China, that are attracting an increasingly diverse array of investors. Rising income and demand growth in many emerging markets are creating greater and sustained demand for natural resources. These changes are contributing to a positive ToT shock in commodity-exporting countries. A country’s ToT are a ratio of its export prices to import prices. Improving ToT suggest that exports prices were rising faster than import costs so that they contributed to a positive growth force.

For commodity currencies, both trade and capital flows are supportive of boosting their long-term fair values. Many investors are trying to gain more EM exposure, demanding EM currencies by selling USD. Even many central banks are trying to increase their EM currency exposure and reduce the share of USD assets in their FX reserves, albeit at a very slow pace. International Monetary Fund (IMF) data show that the average share of central banks’ FX reserves denominated in so-called “other currencies” had risen to 5.1% by 2011 from 1.8% in 2007, while the share of USD in these FX reserves had gone down to just over 60% from almost 90%.

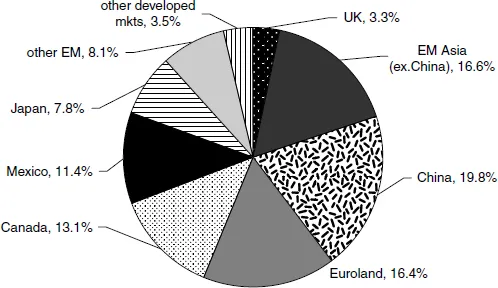

The main beneficiaries from these structural changes will be EM currencies and commodity currencies. This new-world order for key emerging markets could risk pushing the fair value of the USD lower, and reinforcing the need for strategically diversifying away from the US currency. The impact of these EM currencies on the USD’s fair value could be significant, as commodity and EM currencies now account for over 51% of the weights in the USD trade-weighted basket (Figure 1.1). This is not to say that the dollar would be on a one-way depreciation trend. There will still be periods of dollar strength due to its safe-haven status, as witnessed during the Lehman crisis in 2008 and the on-going Euro-debt crisis that started in 2010. Rather, the point is that diversifying out of the USD is becoming a secular trend that will erode its global dominance over time.

Figure 1.1 USD trade-weighted components (end-2011)

Source: US Federal Reserve.

Euro uncertainty persisting

Since its inception in 1999, the euro has faced numerous stumbling blocks, including rules without adequate enforcement mechanisms. Specifically, the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact, created in preparation for an integrated Europe with one currency, said that European Monetary Union (EMU)3 members needed to keep budget deficits within 3% of GDP and the debt-to-GDP ratio within 60%. Countries that broke these rules were supposed to be warned and then sanctioned. But for many years, peripheral countries in the spotlight since late 2010, when the Euro-debt crisis broke out, have run budget deficits and debt-to-GDP ratios many times higher than the Pact allows. Even the EMU’s core country, Germany, has run fiscal deficits more than 3% of GDP for 5 out of the 12 years since 1999 without the EMU authorities taking action.

Thus, the euro has never gained much international confidence in its sustainability. Milton Friedman, the Nobel Laureate, once said before the launching of the euro that the new euro would not last for more than a decade. Well, it is now more than a decade and the euro still stands, albeit with increasing cracks that have generated even more dire predictions for its demise. The on-going Euro-debt crisis only aggravates the fears of a euro break-up (Van Overtveldt 2011).

Solving Europe’s crisis will probably require even greater integration than currently exists and a stronger ability to oversee member states and enforce economic stability rules. But getting from here to there will be very difficult, as many European states fear that giving up more sovereignty to supranational bodies will erode th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- 1 Renminbi Shakes Up Global Currencies

- 2 A Not-so-Mighty Yuan

- 3 From Money to RMB-nisation

- 4 Trade Is not Enough

- 5 The Next Steps for Internationalisation

- 6 China Ready for a Globalised RMB?

- 7 Creeping Reforms Raise Systemic Risk

- 8 RMB-nisation Needs Offshore Market

- 9 RMB – The Third Major Reserve Currency

- 10 The Reality behind RMB-nisation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index