- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Political Communication and Cognition

About this book

Political Communication and Cognition draws on a range of theories from communication psychology to explain how citizens receive communication about politics, how communication might make a citizen think and importantly what stimulates political participation, whether simply paying attention, chatting online or going to vote.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Political Communication and Cognition by D. Lilleker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & American Government. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Strategic Political Communication

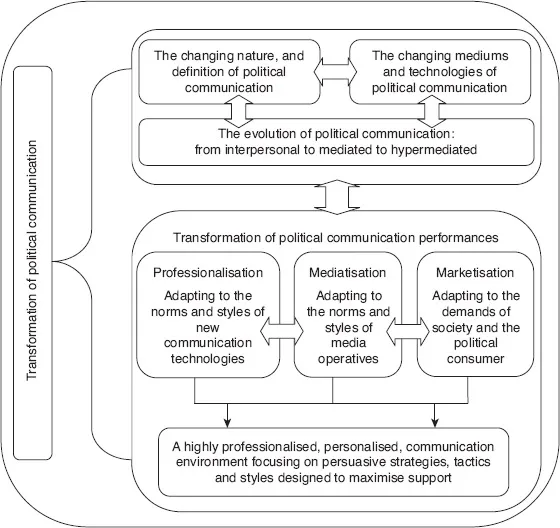

It is argued that political communication has gone through a process of transformation. The transformation is depicted in Figure 1.1, but the chapter contextualises the transformation within current literature and practices of political communication. Political communication is argued to have simultaneously passed through three interconnected processes: professionalisation, mediatisation and marketisation. These processes are argued to have shaped the strategies and tactics of political communicators and have had a profound impact upon the publics’ levels of trust, engagement and participation. The professionalisation of political communication describes the way that politics has adapted to new forms and styles of communication and new means of transmission in order to reach their audience. It is argued that professionalisation is driven by media, and adapting to the communication forms of media; we find ourselves today in the hypermedia age, with the Internet competing against television as the prime vehicle for political communication. Whether this changes the substance of political communication, the content of the message or just the presentation style will be explored further in this chapter. Secondly, and related to professionalisation, we turn to mediatisation. Mediatisation describes the process by which political communicators adapt to the working practices and patterns of journalists and editors in order to gain coverage. The adaptation to the demands of the media is linked to, as well as in some cases competes with, the notion of marketisation. Scholars within the field of political marketing literature argue that, in terms of design of policy, messages and slogans, and the means of communicating, it is the market, the consumers or audience that hold the power. All communication is thus highly strategic, designed with impact in mind, and these broad theories that help to explain the development of political communication will be used to contextualise cognition and the processes by which we receive political communication and what impact it has upon us.

Figure 1.1 The transformation of political communication

The professionalisation of political communication

Colin Seymour-Ure (1977) suggested that political organisations adapt their communication to suit the dominant media of the day. This process of adaptation can lead to a simple re-orientation of communication or to significant changes to the organisation itself. Media is not the only imperative, however. The importance of the media is driven by societal changes and the relationships between society and political organisations. Since the 1960s there has been a decrease in partisan loyalty, referred to as dealignment, with an attendant increase in voters willing to change their allegiances, and so voting behaviour, between election contests (Lilleker, 2002; Clarke et al., 2004). More recently, electoral political organisations find themselves competing with a range of single issue pressure groups that, enjoying celebrity support and tapping into highly emotive local, national or global issues, are able to drain support and activism away from electoral political organisations constrained by realpolitik (Rodgers, 2005; Micheletti, 2003). The 21st century communication environment is highly cluttered with multiple sources of information, catering for every niche interest. The plethora of television stations, newspapers, magazines, websites, Facebook accounts and Twitter feeds all constantly add to the clutter. To be heard is a challenge. This section maps academic works on the evolution of political communication, campaigning and electioneering in order to provide an overview of how we now understand these as professionalised activities.

In terms of the adaptations of political communication across the last half century, Norris’ (2000) typology is in this context a useful heuristic. While the terminology is much contested, in particular the characterisation of eras as pre-modern, modern and post-modern (Negrine, 2008), her schematic reinforces a shared conceptualisation of change within a historical timeframe that elides with studies that introduce campaigning ages (Blumler, 1990), campaign styles (Gibson & Rommele, 2001), market orientations (Lees-Marshment, 2001) or organisational styles (Katz & Mair, 2002).

The first or pre-modern age, prominent until the 1950s, was a time of easy access to a largely deferent media; voters held fairly stable partisan attachments and so parties could stand largely on a consistent product-oriented platform. The platform was designed around clear ideological precepts and presented to citizens as the ‘right’ choice for the country. Campaigns were local affairs, run by decentralised volunteer groups. This was the era of mass membership and so a labour-intensive campaign was both tenable and appropriate. Core to the pre-modern campaign were the face-to-face elements, public meetings, street rallies and doorstep campaigning. While these remain visible (Nielsen, 2012), they have become peripheral elements. It is important to note the pre-modern age was not simply a time of amateurism: Wring’s (2005) history of the UK Labour Party, and observations from the US at the turn of the century (Scammell, 1995) show clear evidence of strategic thinking and professionalism. However, arguably cognition was a much more simple process. The strong relationship between the voter and a party led to internal negotiations based on the belief that the party or leader knew best. While it is true that not all voters were lifelong partisans, there were no cases where the voter felt that the party had moved away from its core principles, so abandoning their vote. The stability of voter allegiance did not necessitate highly persuasive environments; rather, election campaigns were built around statements of key aims reinforced with strong local face-to-face communication.

Television is argued to have ushered in the modern era or second age of political communication (Blumler & Kavanagh, 1999). This led to campaigns developing a more national character, and the beginning of a centralisation of strategy and a professionalisation of communication. With partisan loyalty noticeably declining (Manza et al., 1995), campaigning became more sales-oriented, focused upon converting and persuading voters while also getting the loyalists out to vote on election day (Lees-Marshment, 2001). Rather than focusing on the partisan press, radio, posters and interpersonal communication, television became the key medium, supported by targeted direct mail. Television gave politics a more visual dimension. In particular the image of leaders became more important for voters when evaluating who to support (Keeter, 1987). Voters had to be convinced that a leader was trustworthy and possessed the abilities to lead the nation (Bean & Mughan, 1989; Pillai et al., 2003). Thus persuasion became predominant within political communication, and advertising and public relations specialists were given key roles in designing both the strategy and tactics for campaigning (Wring, 1999).

The 1990s saw a further ramping up of professionalisation, ushering in the post-modern campaign era. Political organisations adopted a market orientation to their communication, as well as to some extent the design of key political messages and policy priorities (Lees-Marshment, 2001). Citizens became likened to consumers, demanding in their expectations but fickle with loyalty; so requiring that parties tailor their programme for the delivery of satisfaction to a core demographic. In multi-party systems this may not be problematic, but in the UK and the US particularly this leads to the production of very broad deliverables that match the preferences of a majority of citizens. Post-modern campaigns also became more targeted, narrowcasted via direct channels of communication; these channels incorporated the mass media as well as direct communication via email, online forums and intranets (Norris, 2000). Targeting aids the delivery of specific messages about promises to specific voter groups. In addition, political organisations adopted a more bifurcated strategy for their campaigning; while the central campaign command set out the core messages, communication was also the responsibility of local organisations, in particular the use of local email lists, intranets for party members, and localised member forums (Gibson & Rommele, 2001; Katz & Mair, 2002; Norris, 2000). Over time, local organisations would also be partially responsible for using social networking and microblogging tools to reinforce and make locally relevant the national campaign strategy (Southern & Ward, 2011).

The extent to which the third or post-modern age is becoming the age of the Internet, as previous eras were interpersonal or television ages, is a moot point. Campaigns have clearly been adapted to a digital media landscape characterised by ‘abundance, ubiquity, reach and celerity’ (Blumler & Kavanagh, 1999: 213). However, it is argued that even in 2011, it is the 24/7 mass media that remains dominant for campaigns across Europe (Lusoli, 2005), as well as in the US during the most recent presidential campaigns (Smith, 2011). Yet we find new ways of characterising campaigning that are designed specifically for the integration of the online environment. Howard (2006) defines the adaption of political communication to the social uses of digital communication technologies as ushering in the era of the hypermedia campaign. Howard argues that political communication is now relayed across a wide range of outlets simultaneously, thereby meeting the demands of a 24/7 news, and a global online audience (Davis, 2010). Any single item of content will be tailored for multiple forms of consumption and disseminated in ways that can be collected by journalists, supporters or web browsers alike at multiple communication junctions. While there will be an informational component, retaining the persuasive emphasis to messages, a range of interactive actions are also facilitated. Items are created to allow ease of sharing to facilitate messages going viral across the Internet (Boynton, 2009), and political organisations may find value in permitting the online audience to comment on and adapt messages. We therefore find political communication now existing not within a broadcasting environment, involving dissemination, but within an ecosystem. Media feed media, from YouTube to main news channels, from newspapers to Twitter and back (Chadwick, 2011). This hybridised media environment may be converting passive audiences into active participants, although it is suggested that this occurs only among a minority (Norris, 2003; Norris & Curtice, 2008; Hindman, 2009). Regardless it provides a more complex agora, where multiple voices compete for attention, where multiple messages can be read, adapted and further disseminated, where official and unofficial communication may be blurring, and where persuasion is harder to achieve.

Howard argues that the hypermedia campaign must allow for and expect the ‘decomposition and recomposition of messages’ (Howard, 2006: 2). These communicative processes permit co-ownership of communication across a wider agora and for reach of messages to be multiplied across networks. While this appears to be beneficial for participatory democracy (Briscoe et al., 2006), there are also threats associated with the use of technologies within the hypermedia campaign (Stromer-Galley, 2006). Howard argues that while it enables greater public communication, technologies also permit greater targeting of communication. The extensive use of data-mining and targeting can lead to a communicative divide. As noted in other critiques of political marketing and campaigning (Lilleker, 2005a; Savigny, 2008), only a privileged few voters may be positioned at the heart of the campaign, having messages constructed for their consumption and being invited to offer their input. The use of interactive communication platforms thus creates a paradox. On the one hand, the creation of an integrated communicational ecosystem offers greater democratisation of political communication and a flattening of hierarchies, at least in theory (for opposing perspectives, see the utopian Rheingold, 1993; and for a more realistic perspective, see Hindman, 2009). Yet, the imperatives of electioneering suggest the maximisation of votes by mobilising your supporters and depressing the support for rivals will remain a priority within official partisan sites. The messages and their channels can be directed at voters with a high propensity to vote and who are most susceptible to persuasion. Therefore we may simultaneously be witnessing a rich communication environment alongside a weak participatory culture (Morozov, 2011). How individuals are targeted will impact upon their sense of self-efficacy and their tendency to be politically active in any significant sense.

This reductionist strategy of targeting those voters whose participation may swing the result leads to what Howard refers to as a thin democracy, with engagement being managed through the process of targeted communication using email. This contrasts with perspectives that suggest that the broadening out of the ability to produce content can lead to a fatter, if no less unequal, form of democratic participation. The ability to wield political power and exert influence will depend on the size and reach of communication within social and communicative networks (Davis, 2010: 98). Basically, in the online environment communication moves between individuals but is also visible within their networks; the larger the network, the greater the number of people that can potentially be reached; the reach attained is referred to as a network effect. Measurement of a network effect has been discussed widely, its value linked to the number of people within a network (Van Dijk, 2007: 78), with the equation of the number of members squared referenced as one method of evaluation (Anderson, 2007: 21); thus the more connected members of the emergent polyarchy are, and the more they are able to disseminate and/or amplify a message, the wider their reach through the network. However, real value is also related to the social capital of the network effect. The amplification of messages via a network does not simply increase reach but also credibility as individuals act as information hubs to their networks of contacts and friends. These constitute a new information elite (Van Dijk, 2007: 185), which can include established elites such as politicians and journalists as well as individual weblog authors (bloggers) or users deemed credible because of their propensity to share items among their friends and followers. Political communicators seek to maximise their reach, harnessing the power of active members of online networks. There is significant debate, however, around the extent that this practice is empowering and so beneficial for broader political engagement, a point that is returned to in Chapter 8 (see also Lilleker, 2013).

Thus the latest layer of professionalisation suggests the rise of a hypermedia campaign strategist who must harness the online and offline information elite simultaneously. Identifying key information conduits, be they professional journalists, independent weblog authors or Twitter users, strategists must create a synergistic communicative process between nodes within the network. Online actions by political actors (a post to Twitter, for example) feed into communication by online and offline communicators (journalists and bloggers) and these draw hits to other online features such as a campaign website, which generates further sharing or other forms of interaction. Interaction, in turn, can create broader offline and online attention, or resources in the shape of volunteers of donations. The hypermedia campaign is thus the response to the 21st century campaign communication environment; it recognises that to be successful one must join the communication ecosystem.

The mediatisation of political communication

Reflecting on his time as an event organiser in UK politics, Harvey Thomas argues, ‘The first and most powerful image projector today is television. Everybody has access to it and politicians ignore it only if they are thick or arrogant’ (Thomas, 1989: 135). Although written three decades ago, there is much to Thomas’ statement that rings true today. Image is central, and, as a medium for image, television remains ubiquitous. Reaching out to the masses in the 21st century is of course harder than it was in the 1980s or indeed 1990s. The plethora of channels, the competition from online sources of viewable entertainment, new entertainment alternatives to watching television, games for example, mean there is no such thing as a means for communicating to the masses. Yet media, and in particular the mainstream media, remain very important for political communication, and mediatisation as a theory explaining the evolution of political communication reflects this importance.

Mediatisation, as conceptualised and problematised by Mazzoleni and Shultz (1999) has a largely negative influence on politics. They argue that it entails a ‘politics that has lost its autonomy, has become dependent in its central functions on mass media, and is continuously shaped by interactions with the media’ (1999: 250). They argue that the process of mediatisation sees politics transformed in five ways. Firstly, political reality becomes a media construct. Through the process of defining news values, media editors define how the masses view politics, to which aspects of political life they pay attention and so what is important. This perspective on the role of the media links to agenda setting theory (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007), where media do not tell the masses how to think but what to think about. Secondly, the media construct notions of political actors and political audiences and ascribe roles to each. Actors are identified through media attention, their role is defined within the mediatised political reality and news values determine those who are newsworthy. Media audiences are then presented with a pastiche of news of events, interspersed with inputs from or pictures of key actors, within a format that is both informative and entertaining, what is referred to by Blumler (1990) as infotainment. Audience members are seldom given the role of participant and feature rarely as political actors (Lewis et al., 2005). Thirdly, political reporting becomes constrained by the commercial logic of media organisations; this can relate to how news values are determined, the way political news is packaged and presented, and the extent to which political news features within an overall package of news items (Franklin, 2004). Fourthly, in response to a commercial logic that leads to the reduction of political news coverage and the packaging of political news, political actors develop a communicational media logic (Slayden & Willock, 1999). In other words, they learn what sort of images and phrases the news editors find attractive and embed them into their communication (David, 2004). At a local level this may be no more than a member of a parliament ensuring there is a gallery of photographs showing them active within the region they represent (Lilleker & Koc-Michalska, 2013). Such images would be emailed directly to journalists as well as made available on their websites or via Facebook, Twitter or other online filesharing portals. At the more national and strategic level it means ensuring all media impressions contribute positively to the individual’s, party’s or government’s image, it means building soundbites into speeches or interviews to be transmitted by the media, and it means working to the schedule of the editor in order to maximise coverage. Finally, returning to the role of the media, there will be less objective coverage and news may be packaged to match the predilections of the actual or imagined audience, or politics will be portrayed negatively to play on existing prejudices (De Vreese et al., 2001).

Mediatisation is thus an influential force, one that Schrott describes as ‘the mechanism of the institutionalization of media logic in other societal subsystems. In these subsystems, media logic competes with established guidelines and influences the actions of individuals’ (Schrott, 2009: 42). The process at the heart of a mediatised political system becomes one that equates to a game. As Davis (2010) observes, based on interviews with journalists and elected representatives in the UK, the politician seeks coverage and the journalist seeks copy. Both parties need the other and so, as the analogy goes, there is a tango at the heart of political communication. Depending on the context, within each dance episode there is a leader and a follower. Based upon a study of elections in Belgian, Van Aelst and colleagues speculate that under election conditions the parties are best equipped to lead (Van Aelst et al., 2008a); at other points the relationship is more ambiguous and dependent on context. The dancing does not lead to mutual understanding or reciprocity. Perhaps that is largely positive, as many argue that there needs to be a distance between media and political actors in order to achieve objective reporting. However, studies often find that the relationship is built around so many negatives that it leads to a wholly anti-politics bias in reporting (Jackson, 2011) and consequent mistrust of journalists among political actors (for perspectives on this latter point, see Goot, 2002; Brants et al., 2010). One study of the attitudes of politicians and journalists found members of parliament largely possessed a negative image of political journalists, especially those who work on television, arguing they have too much power over the political agenda and can make or break politicians. On the flip side, journalists suggest political actors are prone to distort the picture and will do anything to obtain positive media attention (Van Aelst et al., 2008b). The debate over who dominates in the media-politics dance partnership continues, and studies can demonstrate clear unidirectional influence within certain contexts or nations but not in others (Stromback, 2010).

Mediatisation is underpinned with tw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Thinking Politics – An Introduction

- 1 Strategic Political Communication

- 2 Schema Theory for Understanding Political Cognition

- 3 Political Conditioning

- 4 Peripheral Cues and Personality Politics

- 5 Proximity Politics and Valence

- 6 Emotional Motivations and Deep Cognition

- 7 Thinking Twice

- 8 Political Participation in a Digital Age

- 9 Voting and Voter Decision-Making

- 10 Modelling Political Cognition

- Bibliography

- Index