- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

African Immigrant Families in Another France

About this book

Immigrant incorporation is a critical challenge for France and other European societies today. Black Africans migrants are racialized and endowed with an immigrant status, which carries low status and is durable into the second generation. This book elucidates the conflict and issues pertinent to social integration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access African Immigrant Families in Another France by L. Bass in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Social Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

African Immigrants and France

Introduction to Part I

Part I introduces this research on the Sub-Saharan African immigrant integration experience in France using Chapter 1, Chapter 2, and Chapter 3. Chapter 1 explains how this book project found a title from one immigrant woman’s interpretation of her position in France and provides an overview of the chapters to follow.

Chapter 2 establishes the imperative of examining the integration experience of Sub-Saharan African immigrant families living in France. The national motto advocates for universality as defined by the Republican ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité (translated as liberty, equality, and secular brotherhood) for all. In theory, the French government and its people embrace liberty through democratic principles, equality within the social sphere, and brotherhood through a French secularism, which includes all citizens comprising one community, or a “one and indivisible” French Republic. In practice, the voices of Elizabeth and others suggest that a gap exists between the theory of universality and its practice in daily life. This chapter also details this project’s methodology, data collection, and analysis.

Chapter 3 offers relevant historical and contemporary context relating to policy, citizenship and identity in France, so that the reader may comprehend Sub-Saharan African experiences with social integration à la française (French style). While the Anglo-Saxon model of immigrant incorporation engages with the ethnic and religious community life of immigrants, the French model of immigrant social incorporation embraces universalism by taking a laïque (secular) approach and by considering all individuals, independently or without respect to their origins, to have universal human rights and belonging to the community of France. Immigrants to France become integrated – or brought into equal association and participation within society – by taking on this French orientation. This chapter then provides a critique of this universalism (e.g., Bourdieu 1992; Bourdieu and Thompson 2001; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1999; Sayad 2004 [1999]) and introduces concepts and theory to ground this project focused on Sub-Saharan Africans in France relative to other findings on the immigrant integration experience.

1

Introduction – “Another France”

As an African, you have to insist and demand your rights. I use the same roads, the same stores, but I live in another France. We are different physically and they know my race by my name and skin. Someone in my Bible study who has a 13-month-old got her baby a place in the public crèche [state-subsidized day care]. She is French and white. I put my daughter on the list when I was five months pregnant and now she is 18 months old. I still do not have a place. Why is this woman in front of me? When I ask if there is space for my daughter, they say, ‘Madam, the places are taken. I cannot do anything.’

~ Elizabeth from Côte d’Ivoire, 1 child, 5 years in France

This phrase, “another France,” inspired the book title and comes from the above interview excerpt with a 34-year-old woman, Elizabeth, who migrated from Côte d’Ivoire to France five years ago. She explained to me that in the world of child care in France someone at her income level pays 450 euros a month at a private day-care facility but just 38 euros a month at a public one. Regardless of whether she has these amounts correct, her perception and interpretation of the stratified French social milieu (context) is key to consider. For Elizabeth, there are two Frances: one that offers the Republican ideals of liberté, égalité, fraternité to its citizenry, and another France – her France – where freedom, equal treatment in society, and secular brotherhood are not granted as set out in the universality celebrated within the national motto. And the basis of this national motto comes from Article 1 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793: “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good”1 (Embassy of France in the United States 2014; République française [Republic of France] 1789).

Elizabeth’s experience illustrates “another France” where she and her child dwell with fewer life chances in two ways. First, she believes she was not allowed a place in a child-care center due to her African appearance, which is generally associated with a negative, immigrant status. At the same time, she learned of a French woman, easily identified as French-French by virtue of her name and skin color, who was allowed a space. Second, there is a clear economic disadvantage to this immigrant African woman, because she is not allowed a place for her child in the public crèche. In Elizabeth’s “another France,” she is denied full access to equal treatment by societal institutions because of her status as an immigrant African woman. While all citizens, in theory, are part of a “one and indivisible” French Republic, in practice, Elizabeth is not treated as a full citizen in the social sphere. Rather, public authorities and others in her interactions in French society treat her through her standing of being an immigrant and an African at the same time. Her black skin signifies to others that she may hold immigrant status, and this immigrant classification carries a stigma, which subsequently shapes how others perceive and interact with her. She is affronted with this immigrant status that others project onto her through daily interactions.

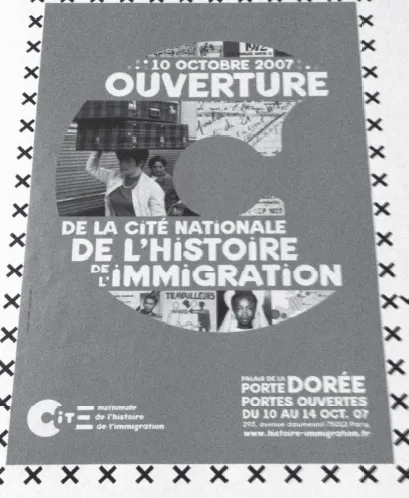

Plan of book

In the pages that follow, I will consider first why it is important to examine both the assimilation and social integration experiences of Sub-Saharan African immigrant families in France. In one sense, France celebrates a rich history of immigration which is reflected upon within the National Museum of Immigration History (Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration) in Paris, and even has a street named rue du Sahel a quick walk away (see Figure 1.1. National Museum of Immigration History, grand opening poster, Paris, 2007 and Figure 1.2. Rue du Sahel, Paris). In another, there remains much work to be done in this area to bridge immigrant peoples from the Sahel to the 21st century community life of France. Earlier research of Sub-Saharan African women’s experiences in France highlight the importance of women’s perspectives on family functioning for immigrant incorporation (e.g., Nicollet 1992; Bledsoe and Sow 2011a; Browner and Sargent 2011; Sargent 2011; Fainzang and Journet 1988). My research draws upon these studies when considering the connections across phantom fathers, polygyny, and public policy in Chapter 3. However, this strand of my research is cast within a broader frame so that we may use African women’s perspectives to understand social integration for African families in broader terms with social structure in France. A few studies have considered the integration experience of North African immigrant women (Killian 2006) and Muslim girls living in France (Keaton 2006), yet there remains much to be understood about Sub-Saharan African immigrant families. This research addresses this gap by drawing upon interviews with African women and young people. I focus on women’s experiences to heed the calls (made by Freedman and Tarr 2000; Killian 2006; Gabaccia 1989) for more understanding of women’s immigrant experiences. Women’s perspectives provide a window on the integration process within the family unit. I include the experiences of young men and women who are either first-generation immigrants or of second-generation Sub-Saharan African immigrant descent. Chapter 2 also discusses contemporary policy responses to immigrant incorporation, as well as a profile of the Sub-Saharan African immigration to France historically. Last, I discuss the methods used in this analysis including the sample frame and the plan of analysis utilized.

Chapter 3 provides historical and more contemporary contextual information to understand the Sub-Saharan African incorporation experience. I detail how a colonial legacy fuels Sub-Saharan African immigration today. A shared colonial history has endowed many African countries with similar institutions and French as an official language. I characterize recent migrants to France as making up a post-colonial bouillabaisse, or fish soup, because they may vary in ethnicity, country or region of origin and religion, yet through the French language and a colonial legacy they create a new life in France. In this chapter, I then discuss how French laws safeguarding individual human rights translate into the government not providing a full count of Sub-Saharan Africans after the first generation. I examine identity and citizenship for Africans living in France and provide relevant background information to comprehend the protests against economic and social isolation (i.e., for equal opportunities and life chances) by young people of immigrant descent that have taken place there. This chapter then attempts to make sense of what respondents refer to as phantom fathers, using prior research in this area on reproduction, polygyny, and public policy (Albert 1992; Bledsoe and Sow 2011a; Browner and Sargent 2011; Sargent 2011; Fainzang and Journet 1988). Additionally, my work disentangles the phantom fathers’ phenomenon as it relates to family functioning and household composition given a larger context of public policies regulating polygyny and providing economic resources through the social safety net.

Figure 1.1 National Museum of Immigration History, grand opening poster, Paris, 2007

Source: Photo taken by author, December 2013. National Museum of Immigration (i.e., Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration)

Chapter 3 then reviews concepts, theoretical approaches, and scholarly findings from France, North America, and elsewhere that are relevant to understand Sub-Saharan African immigrant integration (Alba, Silberman, et al. 2013; Alba and Silberman 2002; Alba and Nee 1997; Killian 2006, Portes and DeWind 2007; Rumbaut 1994; Safi 2006; Zhou 1997). In particular, similar to the experience of Mexican immigrants to the US described by Ortiz and Telles (2008), “assimilation” and “racialization” take place simultaneously for black Africans migrating to France. As a response to black skin color, Africans are assumed to be immigrants and are sorted into the immigrant category. This racialization creates and maintains stereotypes for those of African descent and even structures interactions and life chances for them. Those of Sub-Saharan African descent are lumped into an immigrant status that carries a stigma. According to Erving Goffman (1963), stigma is a matter of visibility, because it is conveyed through an individual’s physical features and then serves as the foundation for further interaction. The individual is continually confronted with this immigrant status that others project onto him or her.

Figure 1.2 Rue du Sahel, Paris

This lower immigrant status may be assigned by the larger, native-born, white-ethnic population regardless of the nativity of the individual. Being erroneously assigned the lower immigrant status is a recurrent finding for the children of immigrants (i.e., second-generation youth) of African descent in France. For these young people who are born in France, it is a stigma that may permeate and injure the individual’s identity and sense of self. Respondents refer to “the power of skin” as a marker of being an immigrant. From The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois’s (1903) concepts of “the veil” and “seeing oneself through the eyes of the oppressor” explain the translation of race status into an immigrant status. Additionally, Fanon’s (1952) Black Skin, White Masks and Sayad’s (2004 [1999]) The Suffering of the Immigrant are used to disentangle the psychological otherness felt by black Africans inserting themselves into the French social fabric in this chapter.

Using survey data, Safi (2006) documents lower labor-market outcomes, or a segmented assimilation, for those from North and Sub-Saharan Africa compared to other immigrant groups in France. My findings on Sub-Saharan Africans reveal that additional segmentation in integration occurs. Although they arrive in France facing similar structural barriers, they harness different sets of cultural resources. Religion is one such differentiator. Sub-Saharan Africans vary in the degree of their assimilation to French culture and additionally in their social integration into French community life based upon religious practice (i.e., whether they are Evangelical Christian, Catholic Christian, or Muslim). In this way, segmented assimilation theory (Zhou 1997) is relevant for understanding their varied negotiated positions and outcomes. As an example, Evangelical Christian women experience greater social integration than their Catholic counterparts and markedly greater social integration than their Muslim counterparts.

From this, I posit that a cultural-materialist framework helps explain observed differences of integration for Sub-Saharan African immigrants, who vary in access to economic, social, and cultural resources. The cultural-materialist approach is both a theory and research strategy, which posits “that human social life is a response to the practical problems of earthly existence” (Harris 2001 [1979]: xv). More recently, Lamont (1992, 2000) used the cultural-materialist perspective to understand varied and patterned outcomes at the group level as being a result of the interplay between the structural context and differing cultural resources utilized as responses.

Part II comprises three chapters. Chapter 4 outlines how the structural considerations related to the government, socioeconomic status, and race serve as the foundation that shapes the processes of immigrants’ assimilation into French society. This chapter uses immigrant women’s voices to highlight their interactions and evolved relationship with the French state as they settle and become incorporated into the society. I use civil servants’ perspectives and other research (Carrera 2006; Keaton 2006) to contextualize these arguments and make clear the unique nature of integration a la française. Indeed, the French government legislates laïcité (French secularism) to ensure personal liberty in the law, but this protection can become a paradox for those Muslim girls of immigrant descent who then face negotiating recently passed laws that ban their wearing of religious symbols such as the veil, at the same time that they are coming of age and to terms with their own identity, politics, and social exclusion. Indeed, I, therefore, profile shifts in legislation in France over the last 20 years that illustrate a chilling of the public sentiment toward immigrants over time. Moreover, African migrant women’s experiences suggest that they are blocked from public services (i.e., child care, a public-subsidized apartment, and job training) by those who work for the French government as well as by the bureaucratic nature of the French state.

Considering social class, Chapter 4 then examines immigrants’ economic status as a structural constraint. A persistent finding is that many migrant women find themselves working for housekeeping service companies or caring for children in the home. Their concentration in housekeeping is problematic because not only is it low pay but much of the cleaning of office buildings gets done at night, and children are left unsupervised at home. In this way, there are spillover effects for children’s home life. The more hours these women labor to get ahead economically in these low-paying, feminized positions, the less time their children have them in the home in the evening hours for what they refer to as a “proper education” in the home. The low economic level of immigrants is a structural constraint, and the low-income jobs open to them are perceived by women to have the unintended and negative consequence of leaving children without supervision. Some women, who have managed to secure positions outside of housekeeping work, find themselves in the internship spiral, floating from one internship position to the next, with the promise of a long-term contract that eventually goes to someone seemingly more “French.” In France, an internship, known as a stage, is a common, on-the-job training program, which lasts from two to six months. A 2012 law requires that all internships of two or more months include a minimum salary of 436 euros per month (Chomage-emploi 2012). With high unemployment, employers can have their pick of potential employees.

The final section of Chapter 4 argues for colorism and race difference, on the one hand, and institutionalized racism, on the other, because social structures serve as a conservative force that constrain the integration process for Sub-Saharan Africans in France. A common refrain among immigrants is, “They know we are immigrants because of the color of our skin.” I use the concept of “colorism” (Harris 2009; Nakano Glenn 2009) to help ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I African Immigrants and France

- Part II Structural and Cultural Considerations

- Part III Theorizing Integration and Conclusions

- Appendix A: Mother Interview Profiles Immigrant Mothers

- Notes

- References

- Index