eBook - ePub

East Central European Foreign Policy Identity in Perspective

Back to Europe and the EU's Neighbourhood

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

East Central European Foreign Policy Identity in Perspective

Back to Europe and the EU's Neighbourhood

About this book

How have countries in the EU that were previously under Communist rule influenced the creation of a European policy towards other Post-Soviet nations? This study explores countries including the Czech Republic and Poland and shows how they have helped develop a coherent policy based reconciling political and historical foreign policy identities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access East Central European Foreign Policy Identity in Perspective by E. Tulmets in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The ‘Return to Europe’ and the Definition of East Central European Foreign Policy Roles in the Eastern Neighbourhood

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, EU and NATO accessions became clear priorities of the East Central European (ECE) foreign policies. The ECE states’ relation with the direct neighbours was also a recurrent issue. However, their policy towards the former communist bloc was marked by ambiguity: some countries, like Slovakia and Hungary, tried to keep good (economic) relations with Russia, while Poland and the Baltic States were more critical towards their large Eastern neighbour. The countries situated between the enlarged EU and Russia became a foreign policy priority for the ECE countries only around 2003–2004, at the time of their EU accession. In order to investigate the policy of the Central Eastern European countries in the EU’s neighbourhood, one first needs to understand the ‘return to Europe’. The redefinition of foreign policies not only took place in the larger context of EU/NATO accessions but also within the context of the EU–United States (US) and especially the EU–Russia relations. It is only after some years of battling to enter these structures that the ECE countries started to define other similar foreign policy priorities and to express solidarity with and responsibility towards the Eastern post-communist countries. This part of the book will therefore mainly focus on foreign policy identities, the return to the West and the definition of the ECE countries’ new relations with the East as expressed in policy discourses.

Investigating political and historical identities in foreign policy

As we have explained above, when looking at foreign policy identity, one needs to focus on the presence of political and historical identities. The political identity represents the core foreign policy directions defended by the political parties and society. The historical identity is the basis on which differences can be generated, depending on the myths constructed, the narratives developed and the relations envisaged with the West and with the country’s past. One then needs to see if there are some contradictions or incompatibilities between the political and historical identities.

This opens the question of continuity and change in foreign policy, a question which is particularly interesting if one truly believes that the ECE foreign policies were defined anew after 1989. The case of the definition of new foreign policy goals after the completion of the EU and NATO accessions is interesting to investigate as it is here that foreign policy roles have a say. We conceive a foreign policy role as a social construction resulting from a certain coherence between the political identity and the historical identity. If a coherence between the two identity elements exists, then a foreign policy role is assigned to the country. However, this foreign policy role can evolve, as one cannot hinder the expression of various, sometimes competing foreign policy positions. If a foreign policy role is identified, then one can check if there the foreign policy behaviour is consistent with the foreign policy identities (developed in Part II). If consistency between the foreign policy identity and the behaviour is difficult to find, then there is no specific foreign policy role assigned to the country in the region under study. In order to narrow down the field of research, the analysis will concentrate on the ECE countries’ definition of foreign policy goals after their EU and NATO accessions. As the Eastern post-communist states fall under the newly defined priorities of all the ECE countries, the ECE countries’ relations to these states will be investigated at more length in this part and the following part. Looking at the ECE foreign policy towards the Eastern post-communist countries indeed represents a way to investigate how ECE identities have developed again in a post-EU-and-NATO-accessions context.

Solidarity with and responsibility for post-communist countries as an expression of political and historical identities

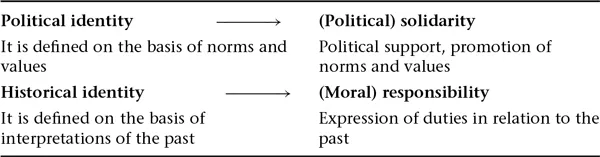

While having this general framework of analysis in mind, one may investigate the further translation of the ECE countries’ foreign policy identities through two related concepts – solidarity and responsibility. The bureaucratic aspects of the relations between the EU and the countries around the EU often downplay the historical dimension of foreign policies. We will try to go into the historical dimension in order to determine if the ECE countries’ relations with the Eastern post-communist countries have been defined more in terms of solidarity or responsibility. We understand (political) solidarity here as the will to support the diffusion of the norms and values building the political identity of the ECE countries, mainly EU and NATO values, which focus on democracy, human rights, the rule of law and market economy. (Moral) Responsibility refers more to the historical identity and implies duties deriving from the past relations of the ECE countries to the Eastern post-communist countries (Table PI.1).

This way, it is possible to see if the foreign policy role of a country has translated more into solidarity or responsibility, or both, depending on the weight assigned to political priorities and to the historical past in the partner country or region under study. Eventually, as will be explained later, the crossing of the political and the historical identities will allow for the identification of a specific foreign policy role for each of the countries under study or, on the contrary, of contradictions in the countries’ foreign policy due to a clash between political and historical identities.

The first part of this book therefore concentrates on the political identity (Chapter 1) and the historical identity (Chapter 2) of the ECE foreign policies as seen through the lenses of political discourse, politico-administrative actors and public opinion. It then looks in more detail at the relations between the ECE countries and the Eastern post-communist space in identifying the foreign policy roles assigned by the ECE countries in this space. It will eventually be checked in regard to which countries in particular the ECE countries expressed solidarity and responsibility as a way to stay consistent with political and historical identities (Chapter 3).

In order to tackle the issue of ECE foreign policy identities in the years 1990 and 2000, it is essential to not only rely on the mainstream literature in English but also consult the literature produced in the ECE countries, may it be in English, French, German or in the national language of the country under study. Also, semi-direct interviews with civil servants, diplomats and experts help us to gain an in-depth picture of the policies analysed. Opinion polls prove useful for reflecting the interest of the population in certain foreign policy issues and for counter-checking the presence or absence of an interest in a region on their part. Then in a more sociological approach, interviews with members of NGOs highlight the role civil society can play in launching debates and influencing implementation of external relations. This way, one might escape the traditional lens of politico-administrative actors and give a manifold view on specific foreign policy issues. It is furthermore a way to value the role of transnational actors in the making of the post-national foreign policy of the EU.

Table PI.1 Foreign policy identity and its further translation

1

The ‘Return to Europe’: Redefining ECE Political Identities after 1989

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the new leaders of the ECE countries have called for a ‘return to Europe’. This was not only a symbolic declaration to celebrate the end of communist dictatorship. It also meant that there was a chance for the ECE nations to not only become sovereign, democratic states but also enter the European Community/EU and NATO in order to ensure stability and security for their new democracies. The metaphor of the ‘return to Europe’, understood as ‘a means of imagining and, by the same token, constructing social reality’ (Hülsse 2006: 397; see also Drulák 2004), has been largely used in political discourses and statements of ECE politicians after 1989. For Judy Batt, ‘the notion of “returning to Europe” usefully captures an essential fact of life in this region: the inseparability of the internal and external dimensions of politics’ (Batt 2007: 16).

Various meanings can be attributed to the metaphor of the ‘return to Europe’ or ‘back to Europe’. First of all, it does not mean a return to the Europe before the conference of Yalta (1945), which then divided Europe into two blocs controlled by the Western allied forces and the Russian ones respectively. The ‘return to Europe’ effectively meant the disappearance of a physical and ideological barrier on the same continent, be it in the form of the Iron Curtain or ideological divisions. The fact that several Soviet republics could regain their sovereignty and that the Czechs and Slovaks could build two independent nation states proves that the ‘return to Europe’ was carried out according to criteria defined by Western Europe and other international organisations and actors.

In the case of ECE foreign policies, it seems that acceding to the EU and NATO was mostly understood in the sense of coming back to modernity. As a matter of fact, the post-war recovery was followed by decades of economic growth and radical technological innovation. The Western European societies became more prosperous and enjoyed the additional security of state welfare provision. Furthermore, ‘the problem of German power seemed to have been resolved by binding its larger Western part, the Federal Republic, into political and economic integration within the European Community (later European Union) and military integration in NATO’ (Batt 2007: 15). ‘Back to Europe’ thus strongly referred to other metaphors like the one of ‘joining the same family’, ‘entering’ what used to be the previous ‘common house’ and, more generally, ‘coming back to modernity’ with a set of norms and values (Drulák 2004; Hülsse 2006).

Like Pál Dunay writes, ‘the role of the EU has been economic integration, that of NATO to provide for security and [that] of the Council of Europe to give recognition to the success of democratic transition’ (Dunay 2003: 69). At the beginning of the 1990s, there was indeed a relative consensus among political parties of the ECE countries on the new political self : it was based on Western values, the promotion of democracy, human rights, good governance and market economy, which the EU (and the Council of Europe) could guaranty, and stability and security through NATO membership. It was mainly defined against the experience of communism, which was characterised by the absence of liberty of movement and expression, repression, control by the secret police and fear.

In the context of the 1990s, what used to be the official self before 1989 suddenly became the other from which the new democracies were to take distance. Foreign policy goals were defined accordingly: the European Communities/EU and NATO were to become part of the political self and not represent the other anymore. Before going into the details of modern-day ECE foreign policy identities, one first needs to recall the overall context of the analysis. Context is indeed important for understanding how a nation defines itself, what its origins are and against what it defines itself. After 1989, the young ECE countries have mainly constructed their identity against or in reaction to more than 40 years of the communist past.

The Soviet past as the political other

The historical context, may it be political, economic, cultural or social, is an important element to be taken into account while investigating identity. In the case of the ECE countries, it highlights the impact of a ‘critical juncture’, the end of the Cold War, and the change that it introduced in their foreign policies. The constructivist literature has defined a ‘critical juncture’ as a situation which poses a significant political challenge to a group that is likely to undermine beliefs in other sectors and, ultimately, impose an internal debate on the basic elements of a group’s identity (Marcussen 2000; Flockhart 2001; Lucarelli 2006). ‘The extent to which a critical juncture is perceived as an ideational shock depends on the identity of the group in terms of both “contents” (core values) and “cohesion” (the extent to which a threat to such values challenges the cohesion of the group)’ (Lucarelli 2006: 307).

The end of the Cold War, and in particular the fall of the Berlin Wall and the putsch of 1991 in Russia, may be interpreted as a series of events which opened a large critical juncture in favour of a radical ideological change in domestic politics and in foreign policy. The coming to power of oppositional groups in the ECE countries allowed for a quick reorientation towards the West and a redefinition of the political identity, mainly along universal values, norms and principles as defended by the Council of Europe, the EU, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and NATO. But first, one needs to recall the Soviet times in order to understand to what extent the new political identity was defined against the communist past.

One communist ideology, several pathways

For many years, the ECE countries’ domestic politics and foreign policies were marked by communist ideologies that were all very similar to that which was officially dictated by Moscow. The countries – their governments and parliaments – were driven by a dominating party, the Communist Party, and the economy and society were subordinated to its political control. The communist, Marxist-Leninist ideology was defined as ‘a universally valid “model” that people would follow’ (Batt 2007: 3).

However, communism took different forms in the Eastern bloc, and the ECE countries were holding different statuses: while Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria were part of the Soviet bloc, the Baltic States were part of the Union of the Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR) and had the status of Soviet republics, like Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova, the three countries of the South Caucasus and those of Central Asia. Yugoslavia under Marshall Tito was earmarked by a specific pathway that was very critical to Moscow. Already in 1948, Yugoslavia broke away from the Soviet bloc and developed its own road to socialism known as ‘market socialism’. Central planning was abolished, the political system was federalised and economic ties were built and bolstered by the West. A certain amount of Yugoslavians were also allowed to work in Western Europe (Batt 2007: 5).

But despite these different political statuses, which allowed for more or less political dependency on Moscow, like the specific Yugoslav policy shows, and besides the central role of the KOMINTERN as a structure controlling communist parties’ ideologies, the mutual dependency between the countries of the Soviet bloc was held mainly through two structures: while the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA, also called Comecon), created in 1949 in reaction to the founding of the Economic integration of Western Europe (creation of the Organisation for European Economic ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The ‘Return to Europe’ and the Rediscovery of the East

- Part I: The ‘Return to Europe’ and the Definition of East Central European Foreign Policy Roles in the Eastern Neighbourhood

- Part II: The ‘Europeanisation’ of Foreign Policy Behaviour or the Reconstruction of the Self ?

- Annexes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Author Index

- Subject Index