eBook - ePub

Democratization and Civilian Control in Asia

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Democratization and Civilian Control in Asia

About this book

How can civilians in newly democratized countries ensure their control over the military? While establishing civilian control of the military is a necessary condition for a functioning democracy, it requires prudent strategic action on the part of the decision-makers to remove the military from positions of power and make it follow their orders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Democratization and Civilian Control in Asia by A. Croissant,D. Kuehn,P. Lorenz,P. Chambers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Conceptual and Theoretical Perspectives

1

Conceptualizing Civilian Control of the Military

Politics in any society involves the management of coercive power. This creates a paradox that Peter Feaver describes as the ‘civil–military problematique’:

This coercive power may take the form of a military organization established to protect the interests of one political group against the predations of others. Once established, however, the coercive power is itself a potential threat to the interests of the political group it is meant to protect. … The civil–military problematique is thus a simple paradox: the very institution created to protect the polity is given sufficient power to become a threat to the polity.

(Feaver, 2003: 4)

The ‘old school of civil–military relations’ research (Forster, 2002) considered the civil–military problematique to be mainly the problems of military coups and military regimes. Most of this literature conceptualized civil–military relations as a dichotomy of civilian control on the one hand and military intervention on the other. Consequently, civilian control was implicitly defined as the absence of a military coup d’état or actual military rule (Edmonds, 1988: 93). Such an understanding, however, poses several problems (see also Feaver, 1996, 2003; Fitch, 1998; Desch, 1999).

Conceptually, military coups are only the tip of the iceberg. The coup/no-coup dichotomy, however, raises this most extreme form of military intervention in politics to the position of being the only point of reference against which all other states of civil–military relations are compared (Luckham, 1971). This not only implies that there are no threats to civilian control other than coups, and that other instances of the military asserting its power are acceptable; it also masks the fact that the absence of coups might actually be an indicator of the political strength of the military. A military that can assert its interests in other ways need not stage coups (Feaver, 1996).

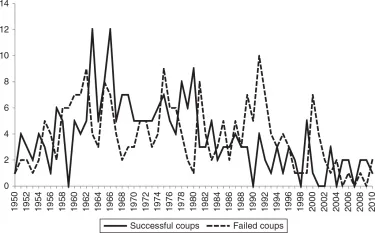

Figure 1.1 Number of attempted and successful military coups, 1950–February 2011

Source: See Figure I.1

Empirically, this is underscored by the real-world developments of the past three decades. The ‘third wave of democratization’ (Huntington, 1991) has made military rule and military coups increasingly rare in most corners of the world. Presenting data for the period between 1950 and 2011, Jonathan Powell and Clayton Thyne (2011) show that the number of attempted and successful coups has declined significantly since the 1960s and 1970s (see Figure 1.1).

The period from 1980 to 2000 also saw a reduction in the number of military regimes from 36 to 11; most of these regimes in Latin America, East Asia, the Near and Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa were replaced either by some form of democracy or by other types of authoritarian rule.1 Consequently, the most pressing problem faced by civilian control in many emerging democracies today is not the avoidance of direct military rule. Instead, civilians are struggling with more nuanced forms of military influence, tutelage, prerogatives, and contestation of civilian authority. These are potentially no less harmful to civilian rule than a military coup but cannot be captured by simplistic dichotomous concepts of civil–military relations.

More recently, scholars have developed alternative approaches that conceive of civil–military relations as a continuum between the two poles of ‘civilian control’ on the one hand and direct military rule on the other (see Welch, 1976; Colton, 1979; Stepan, 1988; Pion-Berlin, 1992; Agüero, 1995b; Alagappa, 2001b; Trinkunas, 2005). Their frameworks propose multidimensional concepts of civilian control and clear criteria for differentiating various states and outcomes of civil–military relations and thereby avoid the conceptual and empirical ‘fallacies of coupism’ (Croissant et al., 2010). Still, they share two interrelated problems. First, while the criteria and analytic dimensions are plausible and the authors are mostly in agreement on the relevant criteria for civilian control, the criteria themselves are not systematically derived from theoretical premises. Second, even though the literature widely agrees that civilian control is of central concern to the meaning and ‘quality’ of democracy, and that the consolidation of liberal democracy presupposes the subordination of the armed forces to the political will of democratically elected authorities (e.g., see Linz & Stepan, 1996), the exact relationship between civilian control on the one hand and (consolidated) democracy on the other remains vague. The following discussion addresses these issues by (1) elaborating on the relationship between democracy and civil–military relations, (2) conceptualizing and operationalizing civilian control without resorting to simplistic dichotomies, and (3) discussing the consequences of military transgressions against civilian control for democracy.

1.1 Democracy and civil–military relations

Democracy is a form of government in which political power exclusively derives from ‘the freely expressed will of the people whereby all individuals are to be treated as equals’ (Hadenius, 1992: 9). This definition highlights three values at the core of most modern understandings of democratic rule: peoples’ sovereignty, equality, and liberty (Brettschneider, 2006). The different understandings of how to realize these principles, however, have led to multiple interpretations of democracy (see Held, 2006). These range from minimalist definitions of democracy (Schumpeter, 1942) that equate democracy with the existence of a functional system of elections and representative government, to ‘thick’ conceptions such as ‘deliberative’ or ‘social’ democracy (Habermas, 1996; Meyer, 2007).

Most of the contemporary empirical research on the transition to and consolidation of democracy, however, is grounded in an institutionalist understanding of ‘liberal democracy’ that takes a middle ground between these minimalist and maximalist conceptions. ‘Liberal democracy’ adds to the electoral minimum the existence of a regime of fundamental civil rights, the rule of law, and the institutionalization of horizontal accountability, as well as civilian control over the military (e.g., see Merkel, 2004; Diamond, 2008).

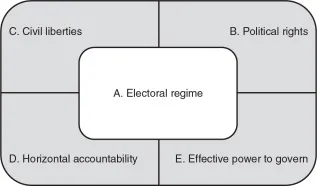

In an attempt to translate the theoretical notion of ‘liberal democracy’ into a conceptual framework, Wolfgang Merkel and his collaborators have developed the concept of ‘embedded democracy’ (Merkel, Puhle, & Croissant, 2003; Merkel, 2004)). At its core lies the assumption that democracy is a set of rules and institutions that can be analytically disaggregated into different ‘partial regimes’ (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The five partial regimes of Embedded Democracy

Source: Adapted from Merkel (2004: 37)

• Partial regime A institutionalizes the principle of peoples’ sovereignty and responsive and accountable rule through universal, free, fair, and meaningful elections.

• Partial regime B complements the electoral regime by providing for the necessary political rights of participation and articulation which are necessary to make elections meaningful instruments of vertical accountability: the rights of free political association and unconstrained information.

• Partial regime C limits the exercise of political power, prevents the abuse of political authority and guarantees individual freedom by providing a set of civil liberties.

• Partial regime D prevents the abuse of state power and ensures interagency supervision through institutional checks-and-balances between the legislative, executive, and judicative branches. The institutionalization of ‘horizontal accountability’ (O’Donnell, 1994) safeguards against the abuse of ‘democratically’ generated power and monitors the lawfulness of governmental actions.

• The institutions of partial regime E guarantee that the ‘effective power to govern’ rests with the elected authorities alone and prevent political actors not subject to the democratic process from exercising political decision-making power.

In this model, ‘the electoral regime’ is embedded in a set of institutional arrangements, rules and practices which each fulfill specialized tasks for the functioning of the democratic system as a whole. If the rules and practices in any of the partial regimes are insufficiently established or cannot fulfill their functions appropriately, the political system deteriorates into some form of ‘defective democracy’ – or even authoritarianism (Merkel, 2004: 43).

While ineffective civilian control over the military affects the proper working of all five partial regimes, the civil–military problematique relates especially to partial regime E. Democratically elected officials’ ‘effective power to govern’ can be challenged by different unconstitutional ‘veto powers’ (Merkel, 2004: 41), that is, individuals, groups, or organizations who have the power to veto the results of democratic decisions or retain prerogatives that cannot be touched by democratically elected authorities (see also Croissant & Thiery, 2010: 72). A list of such actors can be very long, but in any society it is the military which potentially embodies the greatest threat to the elected authorities. This is not only due to the ubiquity of armed forces in contemporary states. More importantly, the armed forces ‘possess vastly superior organization … and they possess arms’ (Finer, 1962: 5) which makes them particularly well situated to challenge the elected government’s effective power to govern (Feaver, 1996; Kohn, 1997: 147). This is not to imply that in a democracy the military has to be an apolitical institution (McAlister, 1964; Edmonds, 1988: 95). The military, as any other organization, has needs and interests, some of which may be legitimate while others may not, and it has a responsibility to advice policymakers on matters of national security. In fact, taking military expertise into account is crucial for effective and efficient defense policies (see Bland, 2001; Bruneau, 2005). The question for civilian control, therefore, is not whether the military yields political influence, but how and how much (Welch, 1976: 2; Desch, 1999: 6).2

From these preliminary considerations we can derive a definition of civilian control. The point of reference is the distribution of decision-making power between elected civilians and the military: Under civilian control ‘civilians make all the rules, and they can change them at any time’ (Kohn, 1997: 142). This means that civilians have exclusive authority to decide on national politics and their implementation. Under civilian control, civilians can freely choose to delegate decision-making power and the implementation of certain policies to the military while the military has no decision-making power outside those areas specifically defined by civilians. Furthermore, it is civilians alone who determine which particular policies, or aspects of policies the military implements, and the civilians alone define the boundaries between policy-making and policy-implementation (see also Kemp & Hudlin, 1992; Pion-Berlin, 1992; Bland, 2001). While civilian control marks the one pole of the civil–military continuum, the other pole indicates full-fledged military rule in which the military dominates all decisions concerning political structures, processes, and policies while civilians possess no autonomous political authority except in areas specifically defined by the military.

1.2 Conceptualizing and operationalizing civilian control

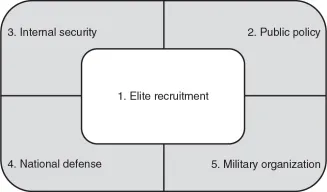

Building on this definition and on insights from Timothy Colton (1979) and Harold Trinkunas (Trinkunas, 2005), we distinguish five decision-making areas in civil–military relations: elite recruitment, public policy, internal security, national defense, and military organization (see Figure 1.3).

This disaggregation allows for a differentiated and nuanced assessment of the extent of civilian decision-making power in each of these areas, as well as a comprehensive evaluation of the overall patterns of civilian control. Full-fledged civilian control, at least in principle, requires that civilian authorities enjoy uncontested decision-making power in all five areas, while in the ideal-type military regime, soldiers dominate all areas. The reality in many emerging democracies, as well as in other regime types, is often more ambiguous and is characterized by spheres of overlapping or shared authority, zones of contestation between civilians and soldiers, the delegation of responsibilities, and informal networking between military officers and civilian elites. The consequences of this ‘power sharing’ for the broader democratic system depend on which of the five areas is affected, how much decision-making power the military exerts, and how it does so.

The question of who decides on the recruitment of the political leadership (Area 1) is of central importance for the distinction between democracy and autocracy: only if civilians are in control of this area can a democracy exist. Any military influence on this area will also affect substantive policies because it will influence who is in charge of making the decisions. Hence, it is situated at the center of the five partial areas.

Figure 1.3 The five decision-making areas of civil–military relations

In addition, the elected authorities in a democracy must be able to decide on all relevant policy matters. Not all substantive policies, however, are of equal importance for the quality of democracy, and some degree of military autonomy is desirable as it allows the military to make use of its specialized expertise and to fulfill its mission. We have therefore further disaggregated decision-making areas according to their relevance for the working of democracy and their relationship to the military’s core function of protecting the state against the predations of others. Both are inversely connected: the farther the distance of a decision-making matter from the military’s core function, the more seriously the democratic principle is undermined if the military has influence over that particular issue area (Pion-Berlin, 1992; Ben-Meir, 1995; Trinkunas, 2005: 7). Decisions on military organization (Area 5) touch upon the military’s institutional core but are rarely decisive for the character of the regime. In contrast, the effective decision-making power of the elected officials – and thus the principle of people’s sovereignty – will be greatly limited if military control extends to general public policies that are beyond the military’s core function of defending the state (Area 2).

Following the definition above, civilian control requires institutions that effectively transfer exclusive decision-making power over pertinent political matters to civilians. Consequently, military constraints on civilian decision making can take two analytically distinct forms (see Stepan, 1988: 68): formal prerogatives that grant institutionalized authority over decision making to the military; and informal contestation, that is, military challenges to civilian authority such as disobeying official regulations, threatening to withhold political support for the government, or staging a coup against the civilian leadership. Not all military attempts to influence the civilian government should be considered ‘contestation’, however. While some forms of assertion, such as a coup or blackmailing civilians, can never be reconciled with civilian control, lobbying for funds or promoting certain policy decisions are perfectly acceptable (Finer, 1962; Kemp & Hudlin, 1992; Ben-Meir, 1995). Contestation, therefore, only refers to those instances in which the military either attempts to enforce its will by threats or actual use of coercion on civilians or openly or clandestinely disobeys orders and challenges existing institutions of civilian control.

By identifying the extent to which effective civilian institutions have been established and remaining military prerogatives and patterns of contestation circumscribe civilian decision-making power, civilian control over each area can be measured on an ordinal scale with three intensities: high, medium, and low. Civilian control in a given area is high if the military does not enjoy formal prerogatives and does not contest civilian authority. It is medium if the armed forces, due to formal regulations or informal challenges to the civilian leadership enjoy political privileges but are unable to monopolize them, or if civilian decision-making authority is not institutionalized but depends on the personal rapport of civilians with the military. Civilian control is low if the military dominates decision making or implementation in that area. Table 1.1 summarizes the operationalization of the five decision-making areas.

1.2.1 Elite recruitment

The area of elite recruitment defines the rules, criteria, and processes for the recruitment, selection, and legitimation of the holders of political office. The actor who controls this area has the power to define ‘who rules and who decides who rules’ (Taylor, 2003: 7). Following Robert Dahl (1971: 4–6), these rules and procedures can be analytically disaggregated into two theoretical dimensions: (1) the rules of competition, that is, the degree of openness of the political processes, and (2) participation, that is, the inclusiveness of the political competition. In order to gauge the degree of civilian control over elite recruitment, one has to analyze to what extent the military is able to exercise influence over the realization and concrete form of both dimensions. Civilian control over the rules of competition is undermined if relevant public offi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List Of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviation

- Introduction

- Part I: Conceptual and Theoretical Perspectives

- Part II: Democratization and Civil–Military Relations in Asia

- Part III: Comparative Perspectives

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Name Index