eBook - ePub

Financing the Family

Remittances to Central America in a Time of Crisis

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Financing the Family

Remittances to Central America in a Time of Crisis

About this book

Interest in learning how to make the most of the potential developmental benefits of remittance flows has grown worldwide. Financing the Family adds to that body of knowledge with a summary of recent research that emphasizes experimental approaches, focuses on Central America, and analyzes the impact of the recent financial crisis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Financing the Family by Inter-American Development Bank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Accounting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Remittances to Central America: A Link Back Home

Workers’ remittances—funds sent by emigrant workers to persons, usually family members, in their home country—are a major source of income for many Latin American and Caribbean economies. More importantly, remittances are a lifeline for many poor households and justification for splitting up families, sometimes permanently.

Nowhere is this truer than in Central America. Remittances to Central America amounted to about US$11.8 billion in 2005. By 2008, they had grown almost 40 percent to some US$16.4 billion. Although this surge may reflect improvements in data collection, much of it reflects an increase in migration flows, as well as higher remittance flows per migrant.

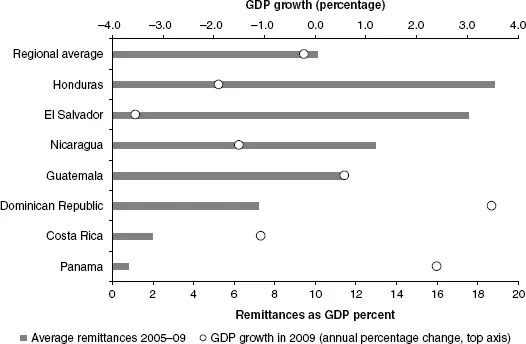

The importance of remittances to these small developing economies cannot be overstated. Remittances represented an average of 10 percent of GDP in Central America between 2005 and 2009. Of course, as shown in figure 1.1, there was substantial heterogeneity across countries, with remittances accounting for 18.8 percent of GDP in Honduras and only 0.8 percent of GDP in Panama. From a regional perspective, remittances to Central America represented about 25 percent of the remittances received by Latin America in 2008 as a whole. Given that Central America made up just 4 percent of the Latin American GDP that year, its 25 percent share of remittance flows is remarkable. Although remittances to Central America are lower than remittances received in some of the Eastern European Countries, such as Tajikistan and Moldova, where they reached 49 and 31 percent of GDP, respectively, in 2008, they are considerably higher than remittances to South Asia, where they made up 4.7 percent of GDP in 2008.1 Notably, figure 1.1 shows that in general Central American countries with higher remittances also experienced relatively larger declines in GDP during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis.2

Figure 1.1 Average Remittances and GDP Growth

Source: Official figures from Central Banks in the region.

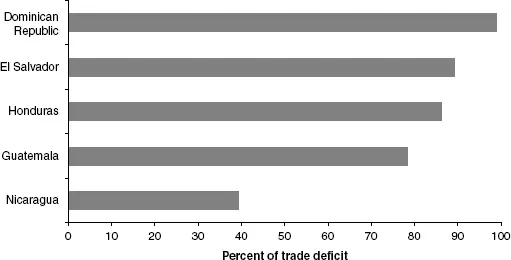

In addition to their importance as a share of GDP, remittances play a vital role in Central American countries’ external accounts. Most of these countries have large trade deficits, and remittances contribute to financing a large portion of these deficits.3 As shown in figure 1.2, remittances on average financed between 80 percent and 100 percent of the trade deficit in the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras between 2005 and 2009, and around 40 percent of the trade deficit in Nicaragua.

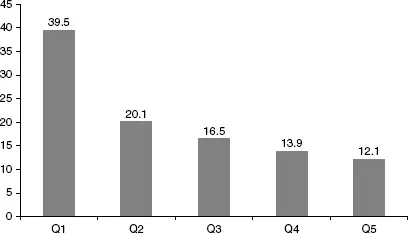

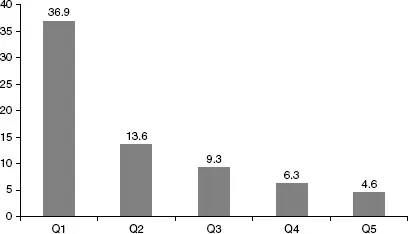

As dramatic as these macro figures are, arguably what matters most about remittances is the support they offer not to these economies as a whole, but to the poorest households in them. Many Central American families depend on remittances to avoid extreme poverty. For example, in El Salvador, 39.5 percent of households in the lowest-income quintile received remittances, according to that country’s 2007 household survey.4 In contrast, the share of households in the second quintile receiving remittances was half that (20.1 percent), while that of the highest quintile amounted to just 12.1 percent (see panel (a) of figure 1.3). For those households that do receive remittances, this source of income represented 36.9 percent of expenditures in the lowest quintile, but only 13.6 percent in the second quintile, and just 4.6 percent in the highest one (see panel (b) of figure 1.3). The extent to which remittance flows are concentrated in the lower deciles of the income distribution within Central America varies by country, however. In comparison to El Salvador, remittances are more evenly distributed across deciles in Honduras, and tend to go to the richest quintiles in Nicaragua (Acosta et al. 2008b).5 The distribution of remittances in Nicaragua seems to be more in line with the experience in South Asia, where middle- and higher-income classes benefit more from remittances.

Figure 1.2 Trade Deficit Financed by Remittances, 2005–09 (Remittances as percent of trade deficit)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Central America’s Central Banks and IMF (2005–09).

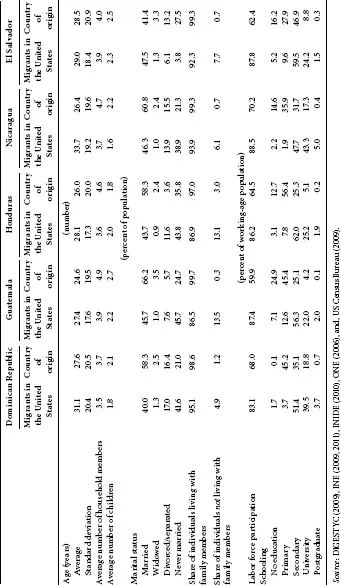

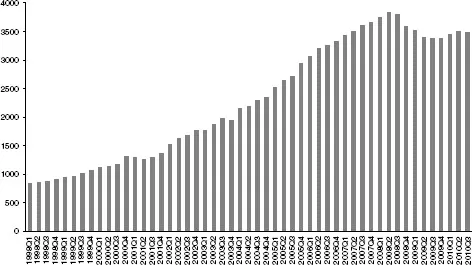

Not surprisingly, it takes a special kind of person to leave his homeland in search of work in a foreign land. Central American immigrants in the United States differ from the population of their country of origin in several respects. In particular, they are more likely to participate in the labor force, are better educated, more commonly single, live in smaller households, with fewer children, and often with people who do not belong to their own family (table 1.1). Although the typical migrant is slightly older than the population of their native countries, this partly reflects the larger share of children in their country of origin. Beyond these general characteristics, it is important to note the heterogeneity between countries; a greater share of Nicaraguan migrants have a university degree and a higher share of Guatemalan and Salvadoran migrants have little or no education. These characteristics are important to the extent that they influence remitting behavior. Up until the recent financial crisis, remittances to the region had proven to be very resilient. Figure 1.4 shows the evolution of remittances to Central America since 1998. Despite concerns about the quality of the early figures on remittances because of problems with the capture of the data, clearly remittances had been steadily increasing over time, showing no major declines. Even during the US recession of 2001, when small declines were observed from one quarter to the next, the comparison of any quarter to the same quarter in the previous year shows steady increases, and a comparison of remittances during the last three quarters of 2001 to the last three quarters of 2000 reveals an increase of 8.1 percent.6 For this reason, some observers were taken by surprise by the decline during the recent crisis, since the resilience of remittances during the previous crisis had provided a false sense of security.

Figure 1.3 Average Remittances and Income in El Salvador, 2007

a. Percentage of Households That Receive Remittances, by Income Quintile.

b. Among Households Receiving Remittances, Share of Remittances in Household Income, by Income Quintile.

Source: DIGESTYC (2007).

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Central American Migrants and the Populations in Their Country of Origin

Figure 1.4 Evolution of Remittances to Central America (US$ millions, seasonally adjusted)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on information from Central America’s Central Banks.

In addition to deterring migration, the financial crisis may also have fueled anti-immigration sentiments. In the period leading up to the crisis, there is evidence of an increase in enforcement efforts and higher migration costs, but little evidence that these trends had a measurable impact on migration or on remittances in the long run.7

The Contribution of This Volume

The size and economic importance of remittance flows has been discussed both within and outside the region, as interest in making the most of the potential developmental benefits of these flows has increased. Although there is a growing body of research on migration and remittances around the world, there have been few attempts to summarize existing knowledge in a way that is easy to digest. A recent World Bank book on lessons from Latin America offers one important contribution in this regard (Fajnzylber and López 2008). The current volume aims to add to that body of knowledge with a summary of recent research that emphasizes experimental approaches and a focus on Central America, as well as an analysis of the impact of the recent financial crisis.

Main Messages

Three main messages emerge from the volume. First, remittances generate a number of positive contributions to economic development. The evidence suggests that remittances are associated with higher earnings of migrants, higher consumption and productive investment, and lower levels of poverty in migrants’ countries of origin. In addition, remittances impact positively on schooling and health outcomes (as measured by lower mortality rates and higher birth weights), as well as on levels of health knowledge and preventive health care. Moreover, remittances may be associated with greater support for democratic principles, as migrants are able to influence political decisions in their countries of origin. However, only very limited research has been done on the long-term effects of migration, including its potential consequences for children who grow up without parents and overall social cohesion.

Second, policymakers can take actions to enhance the development impact of remittances. In particular, through innovative financial instruments, greater control can be given to migrants to boost the share of savings from remittance receipts. Governments can support their migrant communities abroad by actively pursuing ways to reduce remittance fees and facilitating migrants’ access to and use of financial services. In addition, governments can foster stronger linkages between migrants and their countries of origin by extending absentee voting rights to overseas citizens, promoting cross-country enterprise activities, and encouraging migrants to retire back home.

Third, the recent financial crisis exposed important vulnerabilities of Central American countries to a weaker US economy. Both the macro- and microeconomic impacts of the crisis on Central America were substantial, and remittances were one of the main channels of transmission. Given that the strength of the linkages of Central American countries with the US economy vary among US states and sectors, it is useful to examine developments in the United States in a disaggregated fashion, focusing on the sectors and states where migrants are concentrated. This is particularly important for those countries from which migrants tend to be concentrated geographically and sectorally, and thus are more vulnerable to the regional or sectoral shocks frequently associated with crises. More specifically, to the extent that migrants from El Salvador and Guatemala are concentrated in California and Florida and are employed in construction, they are especially vulnerable to real estate recessions originating in those states. In contrast, remittances to the Dominican Republic depend on the economic fortunes of migrants who are concentrated in New York and tend to work in retail.

Making a Difference for Development

What effects have remittances had on the migrants who send them and on the households that receive them? This topic has been explored from a number of vantage points. Recent research identifying causal effects has shown that migration brings dramatic increases (on the order of a quadrupling) in migrants’ earnings. Even when the estimates correct for unobservable differences in the characteristics of movers versus stayers that may lead to an overstatement of the causal impact of migration on wages, migration leads to at least a doubling of wages. What impact does this sizable increase in migrant income have on the following factors?

•On levels of household income and livestock and durable goods ownership: The effect is not always positive. Since the migration decision is determined simultaneously with other outcome variables of interest, a powerful approach in answering this question involves taking advantage of exogenous variation in migration created by lotteries that are held by destination countries among source country potential migrants.

•On levels of consumption and investment: Consumption may be the optimal use of resources for remittance-receiving households, particularly those starting from very low consumption levels. However, for households somewhat above subsistence consumption levels, it is useful to examine whether remittances lead to household entrepreneurial investments, given the implications for longer-run growth of income and other aspects of household well-being. Much of the existing empirical evidence on the issue is mixed. Moreover, a central methodological concern is that migrant earnings are in general not randomly allocated across households, so that any observed relationship between migration or remittances and household consumption and investment outcomes may simply reflect the influence of unobserved third factors.

•On education and health outcomes: A variety of studies that compare remittance-receiving households with those not receiving remittances find that remittances are associated with human capital investments. In particular, the few studies that take advantage of exogenous variation in migration or remittances find positive causal impacts on child schooling (and corresponding reductions in child labor). In addition to the effect operating via higher wealth in migrant households, other reasons for the positive impact of migration include better health knowledge and preventative health care, as well as more prevalent breast-feeding and vaccinations in migrant households receiving remittances.

While remittances can have an important impact on household outcomes, they also respond to what happens within receiving households. At the international level, it is commonly posited that remittance flows buffer economic shocks in migrants’ home countries, but there have been relatively few empirical tests of this claim with micro-level household data....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- 1 Remittances to Central America: A Link Back Home

- 2 Migration, Remittances, and Economic Development: A Literature Review

- 3 Enhancing the Impact of Remittances on Development: New Evidence from Experiments among Migrants from El Salvador

- 4 US Migrant Employment and Remittances to Central America: A Cointegration Approach

- 5 Remittances and Poverty during an Economic Crisis: Honduras and El Salvador

- 6 Measuring the Impact of the US Financial Crisis on Salvadoran Migrants and Family Remittances

- Notes

- References

- Index