eBook - ePub

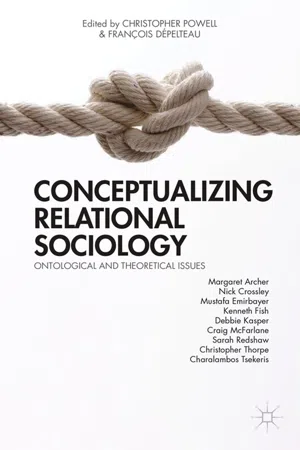

Conceptualizing Relational Sociology

Ontological and Theoretical Issues

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conceptualizing Relational Sociology

Ontological and Theoretical Issues

About this book

Edited by François Depelteau and Christopher Powell, this volume and its companion, Applying Relational Sociology: Networks, Relations, addresses fundamental questions about what relational sociology is and how it works.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conceptualizing Relational Sociology by C. Powell, F. Dépelteau, C. Powell,F. Dépelteau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Feminist Preludes to Relational Sociology

Sarah Redshaw

Feminists have critiqued many of the dichotomies in Western thought such as nature and culture, mind and body, emotion and reason, public and private, and developed critiques of central notions such as individualism and abstract generalization. In this chapter, Nancy Chodorow’s relational individualism, Benhabib’s generalized and concrete other and Gilligan’s “different voice” are discussed, and their relevance to Crossley’s relational sociology is highlighted.

Important aspects of feminist thought have been underutilized, such as an understanding of human being as having a basis in interdependence. Understanding interdependence and relational individualism within a contextual framework shows how these notions can inform current issues relating to women and women’s bodies within sociology. Modernism modeled human experience on white, European, male perspectives and overlooked or invisibilized others, including women, children, and other races and ethnicities. Feminism is no less relevant and important today in highlighting the experiences of women and critiquing the taken-for-granted perspectives implicit in major paradigms.

In sociology concerned with health, feminism has highlighted gender inequalities and the role of gender constructs tied to biology, in limiting women’s visibility in health and medicine.1 There remain nevertheless important areas where gender is implicated with other constructs of Western thought such as individualism, in limiting and controlling women’s experiences. The chapter will discuss how women’s agency is subordinated and excluded in biomedical interventions with infants. Notions of individuals as isolated and separate have led to a failure to incorporate the interconnection between foetus/neonate/infant and mother whose body is most enmeshed with it, into medical decisions and care. The incorporation of feminist critiques and the need for a feminist informed relational sociology in understanding and informing issues such as these is emphasized.

Feminist Critiques

There are two main aspects of feminist critiques that will be the focus of this chapter. The first is the critique of individualism and the second is feminist exposure of generalizations about humans as based on male ideas of being human. A third implication that arises from the second is that differences are subsumed into abstract generalizations and thereby excluded and/or negated. The Western world has had a predominant focus on the independence and autonomy of separate individuals. Individualism has been critiqued by a range of writers in social and moral theory such as Alasdair MacIntyre (1981), Michael Sandel (1982), Charles Taylor (1985a), and Sandra Harding (1987) along with many others.

Attempts to provide alternative conceptions of individuality and autonomy have arisen in many fields from philosophy and social and moral theory (Gilligan 1982) to psychoanalysis (Chodorow 1991) and health. There has also been considerable discussion in the autonomy literature on relational autonomy and interdependence as alternatives to isolated or atomistic individualism (Chodorow 1991, Mackenzie and Stoljar 2000, Christman 2004). Relational views maintain that autonomy has to be considered in the context of sociality, as based in intersubjectivity and interdependence.

Being Human

Ideas of being human have been exposed as based on men’s preferences and ideals of individualism as separate. Women were seen as close to nature and in Enlightenment thought men were seen as surpassing their natural instincts to achieve reason. Genevieve Lloyd in The Man of Reason (1984) gave a feminist critique of the history of philosophy and the ideals related to reason through maleness and femaleness. For much of the Western tradition women were excluded from reason and not considered as able to attain independence. Lloyd’s analysis highlighted the male norms predominant in philosophy, through which women have been judged as inferior.

Individuals in industrial societies have been regarded as separate and distinct from others and in early social theories such as Hobbes’s (1968), dependencies of any kind were a source of vulnerability and limitation. Hobbes’s vision of man in the state of nature produced an image of a solitary man living on his own means, alone and completely independent. The man of reason was an image developed within Western thought that involved men being seen as capable of independent thinking completely free of the influence of others (Friedman 2000). These images required no sociality for men in particular, though women were seen to be dependent and requiring social ties.

Much moral and scientific thought has been based on the man of reason and his ability to reason objectively, free of the constraints of belief, values and assumptions, and most of all emotions (Gilligan 1982, Harding 1987). The idea of any man being independent of society, or particular beliefs and values, has been thoroughly critiqued. Men’s individuality is no less relational despite being cast as independent of relations in many philosophical, psychological, and moral accounts. It is clear from these critiques that there has been an emphasis in mainstream political and social thought on individualism over relationalism.

Feminist work continues to challenge major paradigms and produce new methods in many disciplines including in sociology. The work of Chodorow, Benhabib, and Gilligan has had a significant impact in a number of disciplines as well as highlighting and informing feminist debates on women’s experiences. They are examples of feminists whose work has challenged fundamental modernist thought, and strengthened the perspective and experience of women as valid and different, in important ways that need to be acknowledged. Their critiques center on the development of a relational approach and all work with relations on interpersonal and social and cultural levels.

The Self-in-Relation

Nancy Chodorow is a sociologist and psychoanalyst who has argued that women experience a “self-in-relation” (1978) in contrast to men who experience a self that denies relation and connection, preferring instead to emphasize individuality and independence. Chodorow argues that classical psychological and psychoanalytic theories privilege separateness and autonomy over connectedness and empathy, and proposes her own theories of subjectivity (1991). Chodorow coined the term “relational individualism” in order to denote an individualism that develops within a context of relations and relatedness and much of her work is concerned with the development of women’s individuality, and resituating and revaluing it as relational.

Her project has been to revalue female psychology and to present not only an intrapsychic and intersubjective account, but also to give a social and cultural account of reproduction and mothering within a male-dominant sex-gender system (2000). Chodorow insists that she is not describing “a universal or essential story, but a pattern” (2000, 345). She maintains that “the psychology of women and men, of femininity and masculinity is more than a psychology of bodily experience” (2000, 344). The social context within which the biological individual exists must be taken into account and this is a context of relations.

The Generalized Human

Seyla Benhabib (1987), a political theorist and philosopher, is another feminist who emphasized a relational perspective. She distinguished between a generalized and concrete other and argued that contemporary theories of justice are dependent on a generalized perspective that does not adequately encompass the concrete interests and needs of individuals. Mead used the phrase “generalised others” to refer to the views and beliefs of groups or communities that individuals are connected within (Crossley 2011, 85). This is a different meaning than Benhabib has in mind. For Benhabib, the generalized perspective has been abstracted from some groups and applied to all, and does not recognize the particular differences within or between groups. In particular, it does not recognize the perspective of women, race and class, except in a negative sense, as it is based on that of white, middle-class men.

Benhabib refers to the ultimate picture emerging from the “state of nature metaphor” employed in contract theories, as the “men as mushrooms” vision. In this vision autonomy is understood as man alone and independent in the state of nature, not even born of woman and so having no ties of dependency. What Benhabib sees as most characteristic of this image, and reappearing in more contemporary moral theories such as those of Kohlberg and Rawls, is the “disembedded” and “disembodied” nature of the autonomous self in which:

moral impartiality is learning to recognise the claims of the other who is just like oneself. (1987, 85)

Benhabib describes this public, disembedded, and disembodied subject of moral theory as the “generalised other.” Whereas in contract theories the other was constituted through projection, in the contemporary theories of Rawls and Kohlberg this is a consequence of total abstraction from identity. The generalized other is contrasted by her with the concrete other that is based on acknowledgement of difference.

Our relation to the other is governed by the norms of equity and complementary reciprocity: each is entitled to expect and to assume from the other forms of behaviour through which the other feels recognised and confirmed as a concrete, individual being with specific needs, talents and capacities.

In order to recognize the other as concrete other, it is necessary to see the individual through and with their “concrete history, identity and affective-emotional constitution.” According to Benhabib this requires seeing individuals in terms of interactive norms that are private and noninstitutional:

In treating you in accordance with the norms of friendship, love and care, I confirm not only your humanity but your human individuality. (1987, 87)

It is not possible to take into account the other’s perspective while their concrete identity is removed from consideration—“the other as different from the self, disappears” (1987, 89). Where the other is understood through the framework of the generalized other only a monologue is possible. The other’s needs, interests, and concerns must be filled out from the perspective of the self judging other, because the other does not appear in terms of his or her own concrete needs, interests, and concerns.

Benhabib goes on to emphasize a relational view that she believes enables the possibility of a dialogue rather than a monologue, through deliberations between distinct selves with particular identities. In a relational-interactive theory the self is seen as a self within a community of selves:

Every act of self-reference expresses simultaneously the uniqueness and difference of the self as well as the commonality among selves. (1987, 94)

Commonality here refers to what is shared between individuals while taking into account concrete differences, rather than the abstract, generalized, or universal notions feminists have argued against.

Moral Difference

A relational view drawn out by psychologist Carol Gilligan in her research on the differences in women’s moral reasoning shows the impact of the separation between the generalized perspective of the public sphere of interactions and the private realm where nurture and compassion are able to be expressed. She discusses studies on sex-role stereotypes, which show that there is a strong association between qualities seen as necessary for adulthood, such as autonomous thinking, clear decision making and responsible action, and masculinity. These qualities were not seen as possessed by or desirable for women. Gilligan takes this to indicate “a conception of adulthood that is itself out of balance”:

The stereotypes suggest a splitting of love and work that relegates the expressive capacities requisite for the former to women while the instrumental abilities necessary for the latter reside in the masculine domain. (1985)

Kohlberg (1981) regarded women as lacking in moral development to the point that they were seen as unable to reach the final and most abstract stage of moral reasoning. Gilligan argued that women had a more contextual mode of judgment and a different moral understanding (1982, 22). Women she found are more likely to see moral problems as arising from conflicting responsibilities rather than competing rights and to require a contextual and narrative resolution rather than an abstract, formal one (1982, 19). Gilligan referred to women as having a “different voice” (1985).

Difference and Experience

The positions of Gilligan and Chodorow have been considered essentialist in that they claim a particular perspective as belonging to women. They have noticed that women have approached things differently from the way in which men see as proper; however they do not therefore ascribe this perspective only to women or limit women to these perspectives. Rather they wish to claim these perspectives as positive and to challenge the male ideal that has been applied to all. The essentialism with which they have been charged is derived from gender stereotypes related to the biological body that they are objecting to and seek to expose. Gilligan notes the association between qualities that are regarded as desirable and those deemed characteristic of men and male domains, while those that are not desirable in the public domain are associated with women and the home.

All of these theorists noticed another way of seeing social relations, psychology, and moral theorizing that they came to by considering women’s “voices,” experiences, and thinking. The alternatives they presented were not necessarily intended to be confined to women or to imply that all women and men are confined to thinking in particular ways. They all develop relational alternatives and critique dominant theories as excluding relationality to focus on a masculine ideal of independence. They expose the ideal as grounded in relationality and emphasize that which the male view has apparently sought to avoid.

In sum, feminists have critiqued a dominant view that they revealed as based on white, male values and from which all are judged. By masking their desires and values as universal, European males were able to dominate not only women but also other races, classes, and creeds by claiming their lack of reason or rationality. The denial of connectedness and embededness in relational contexts allowed a generalized, universal view to be established and to dominate.

One of the major obstacles in engaging with the context of concrete relations is the biological body. Gender has become a common variable and it is largely accepted that it is socially constructed, though as Bradby argues:

The reluctance of feminist theory to grapple with embodied aspects of sex difference in relation to gendered ideas, together with medical sociologists’ fascination with obstetrics, gynaecology and midwifery, has perhaps left undisturbed a Victorian core of thinking that gendered illness patterns are a matter of reproductive physiology. (Bradby, Virtual Special Issue, Sociology of Health and Illness)

Women’s experiences in some part are related to their bodily experiences, some of which are not shared by men. The problem that the sex–gender distinction was intended to solve is the alliance formed between female bodies and women—women are the weaker sex because they have weaker bodies and so on. Engaging with embodiment in a meaningful way that does not limit women, or men, to their biological being is complex and difficult in the context of biology as a dominant discourse. It is not enough to neutralize bodies since embodied experiences are important and qualitatively different. Not all male experiences of the male body are the same, nor are female experiences of the female body all the same. Transexualism presents a major challenge to assumptions of sex–gender alliances and to separations of biology from the social construction of gender where two genders remain (Gatens 1996, 3–20). To recognize embodied experience is to see each in their particularity, though this is difficult in the context of social constructions of the body that are limited to two sexes.

Relational Sociology

Ideas of complete separation, and disembodied and atomistic ideas of the mind such as Descartes’s, are inadequate as accounts of human being, though as ideologies of dominance they have been very successful. The suppression, denial, and invalidation of all other perspectives are the fundamental basis of universalist dominance and this is precisely what feminists have railed against. Allowing other perspectives to be recognized and to have validity has been an ongoing battle in most human disciplines from philosophy to sociology, anthropology and the sciences.

In relational sociology, the focus is not on the atomized individual, but it is on the context within which an individual develops, and this is a context of relations. Crossley (2011) makes the relations themselves the central feature of his relational sociology, and autonomy is grounded in the context of life-giving relations and interactions. Crossley’s approach is to work through issues related to the individual versus the whole, or the “holism” debate. He argues against both individualism and holism, claiming that society...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Feminist Preludes to Relational Sociology

- 2 Relational Sociology and Historical Materialism: Three Conversation Starters

- 3 Relational Sociology, Theoretical Inhumanism, and the Problem of the Nonhuman

- 4 Advancing Sociology through a Focus on Dynamic Relations

- 5 Norbert Elias on Relations: Insights and Perspectives

- 6 Critical Strategies for Implementing a Relational Sociological Paradigm: Elias, Bourdieu, and Uncivilized Sociological Theoretical Struggles

- 7 Interactions, Juxtapositions, and Tastes: Conceptualizing “Relations” in Relational Sociology

- 8 Collective Reflexivity: A Relational Case for It

- 9 What Is the Direction of the “Relational Turn”?

- 10 Radical Relationism: A Proposal

- 11 Relational Sociology as Fighting Words

- References

- Notes on Contributors

- Index