eBook - ePub

The Economies of Urban Diversity

Ruhr Area and Istanbul

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Economies of Urban Diversity

Ruhr Area and Istanbul

About this book

The Economics of Urban Diversity explores ethnic and religious minorities in urban economies. In this exciting work, the contributors develop an integrative approach to urban diversity and economy by employing concepts from different studies and linking historical and contemporary analyses of economic, societal, demographic, and cultural development. Contributors from a variety of disciplines geography, economics, history, sociology, anthropology, and planning make for a transdisciplinary analysis of past and present migration-related economic and social issues, which helps to better understand the situation of ethnic and religious minorities in metropolitan areas today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Economies of Urban Diversity by D. Reuschke, M. Salzbrunn, K. Schönhärl, D. Reuschke,M. Salzbrunn,K. Schönhärl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Economies of Urban Diversity: An Introduction

Darja Reuschke, Monika Salzbrunn, and Korinna Schönhärl

1. Two Cultural Capitals and Their Potential in Urban Diversity

As European Capitals of Culture in 2010 and metropolitan areas of immigration and transmigration, both Istanbul and the Ruhr Area (Essen was designated as European Capital of Culture on behalf of the Ruhr Area) share a complex cultural and social history. Strong human, political, and economic ties have long linked the European Capital of Culture of Turkey to Germany’s main immigration region, which is about to become a new cultural center thanks to the recognition of its industrial heritage by UNESCO (Zeche Zollverein in Essen).1 Even though the cultural history of each region is different, a crisscross reading of ‘parallel lives’ between the two countries helps to understand better the use and the potential of urban diversity over time.

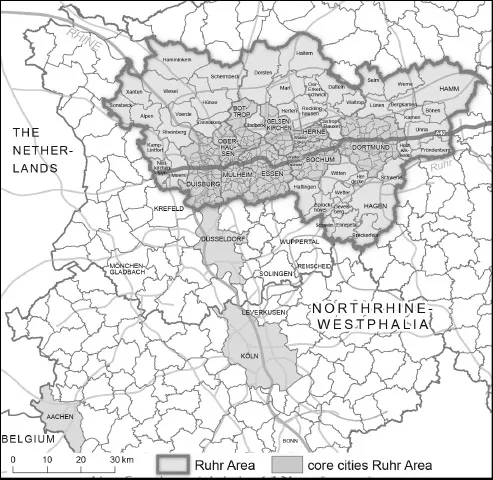

The Ruhr Area and Istanbul are both significantly shaped by their religious and ethnic minorities. In the case of the Ruhr Area (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2), its history cannot be exhaustively told without elaborating on processes of modern immigration that started with the recruitment of Polish mining workers in the nineteenth century. During the second half of the last century, people from Turkey, among others, were increasingly recruited to satisfy the demand for cheap labor in the steel industry. The demographic structure of the Ruhr Area today reflects these diverse migration narratives. This is reflected, for instance, in current discourses in both academia and the public sphere on whether a representation of this migration history by means of a migration museum is a worthwhile project (Baur, 2009; DOMiD, 2012). The Ruhr Area and its future viability are shaped by these cultural dynamics and, more generally, by the potential of this diversity. However, diversity is not always considered an auspicious potential: the incorporation of Muslims in a (historically) predominantly Christian society constitutes a challenge for both sides, especially when it comes to buildings with a representative function in the cityscape. The success of populist parties in various European countries needs to be counterbalanced by fact-based discussion about the economic potential of ethnic and religious minorities. Although Istanbul has a predominantly Muslim population today, it has—like the Ruhr Area—long experience with minorities. A large number of Christians, including, for example, Greek Orthodox and Armenians, lived in the city as indigenous minorities during the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries (Alexandris, 1992).

Figure 1.1 The Ruhr Area within Germany.

Source: ILS Dortmund.

Figure 1.2 Ruhr Cities within North Rhine-Westphalia.

Source: ILS Dortmund.

The population flows between Turkey and Germany are an outstanding example of the complexity and heterogeneity of contemporary migration processes in the Global North. They started in the 1950s and 1960s with the recruitment of guest workers (Gastarbeiter)—‘invited’ workers who were supposed to rotate with others, but finally stayed and were often followed by family migration. Multiple flows of people and goods have developed since. The growing number of journeys, including people going back and forth, between the Ruhr Area and Istanbul indicate how intense the relationship between these two regions has become (see Ulusoy in this book). These are expressions of “new (global) geographies of migration” (Hillmann, 2010). In recent years, the so-called return migration or remigration of Turkish-Germans to Turkey, and Istanbul in particular, has received much attention in public policy and research. This debate is strongly linked with the discussion on brain drain and the migration of the highly skilled (Liebig, 2005; Pusch and Aydin, 2011). The term return migration, however, is not applicable for migratory movements in which the second generation of Turks, who were born and/or brought up in Germany, is involved. Their strong ties to Germany may result rather in circulatory movements.

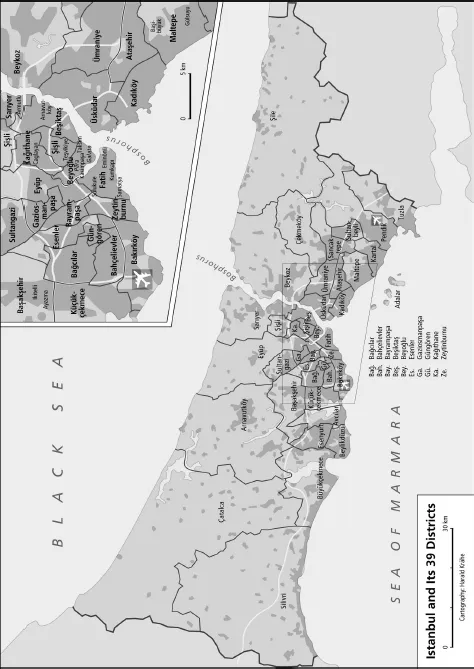

Today the Ruhr Area as a whole and most of its cities (see Figure 1.2) suffer from population decline. As a result of deindustrialization and the closure of coal mines and related industries, many people have left the region in order to find jobs in more prosperous regions. For example, between 2000 and 2011 the region’s population has declined by 4.2 percent to 5.13 million (Regionalverband Ruhr, 2011). In-migration has therefore become a crucial component of efforts to minimize population decline. It is the question whether this situation could contribute to greater willingness among the ancestral population to accept migrants or whether it may rather lead to subliminal fears of foreign infiltration. In contrast, Istanbul still receives significant numbers of internal and international migrants, resulting in the constant growth of the metropolitan area. In 2011 Istanbul had 13.6 million inhabitants distributed over an area of 5.3 thousand square kilometers in 39 districts (TurkStat, 2012) (see Figure 1.3).

The economic development of both metropolitan areas has also been strongly linked to in-migration and out-migration. Historically, both areas’ urban economies used to depend largely on migrant entrepreneurs and workers. While non-Muslim entrepreneurs, particularly Jews and Greeks, were the drivers of Istanbul’s Ottoman economy, the rise of the Ruhr Area as the industrial core of the German economy from the second half of the nineteenth century was highly dependent on Polish migrants, once local and regional resources of coal mining workers had been exhausted. In Istanbul, on the other hand, the flight of non-Muslims from the city as a result of ‘Turkification’ policies in 1923–1924 and pogroms in 1955 changed the economic base and performance dramatically. As a result, the city became predominantly Turkish and Muslim and only little remained of what used to be the cosmopolitan Constantinople where half of the city’s population was non-Muslim (Gökürk et al., 2010, p. 7). With industrialization processes in the second half of the twentieth century, both the Ruhr Area and Istanbul experienced massive in-migration, changing the urban population dramatically. While foreign immigrants, mainly from Turkey, entered the Ruhr, it was rural migrants from the south and east of Turkey that came to Istanbul in search of jobs in manufacturing.

Figure 1.3 Map of Istanbul.

Source: Harald Krähe.

This edited volume deals with ethnic and religious minorities in urban economies: the main interest being economic and social issues and the opportunities of urban diversity. At the same time, endogenous potentials are relevant. These are discussed with regard to their utilization in economic development. Previous literature has looked at culture and art in cities and has explored the intertwinement of cultural and economic issues by addressing the economic impacts of cultural events (Göktürk et al., 2010). This volume adds to this research by employing a wider approach using concepts of urban diversity, superdiversity, and ethnic entrepreneurship, and highlighting the linkages between urban diversity and economy in a historical context. It also gives an innovative reply to critiques of methodological nationalism in the migration literature (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2011) by linking social geography, urban studies, and social and economic history to migration studies. It aims to develop a novel perspective on the economy of culture and diversity by taking a transdisciplinary approach and dealing with ethnic and religious minorities from a diachronic and synchronic perspective. This contributes to a better understanding of the incorporation processes of the ‘other’ in an urban fabric.

By focusing on Istanbul and the Ruhr Area, this book pursues the questions of how diversity in ethnical and religious terms represents itself, how it is communicated, and, more specifically, how it is merchandised (or not). It asks for traditions and concepts about how to deal with ‘the other’. Thus, the contemporary perception of diversity in the Ruhr Area is highlighted and mirrored with the past and present situations in Istanbul, thereby unraveling the incorporation processes of the ‘other’ in these metropolitan areas. How was the economic potential of urban diversity in the Ruhr valued in the nineteenth century and during the guest worker period of the twentieth century? How did the Ottoman Empire deal with the religious and cultural diversity of its inhabitants, compared to the Ruhr Area? What kind of conflicts with the majority population emerged during the Ottoman Empire and how were they communicated and reconciled? Past developments and experiences are furthermore applied to present urban contexts. To what extent are there continuities in the way Istanbul handles its minorities in past and present? Has the situation of the minorities changed over time? What new inequalities in the metropolitan area of Istanbul can be observed today through residential segregation and state-led urban regeneration? How is the cosmopolitan past of Istanbul perceived and exploited in present economic and urban contexts? And to come back to the German Capital of Culture: is the situation in Istanbul comparable to the situation in the Ruhr Area? Why is migration in the Ruhr and Germany, as in Istanbul, more generally perceived as a challenge rather than as a benefit? Studying historical and contemporary issues of urban diversity in Istanbul and the Ruhr Area helps to understand better the situation of ethnic minorities in metropolises today.

In both past and present times economic factors have played an important role for the success or failure of immigration processes, and the role of networks and related structures are crucial for urban economies. It is therefore important to investigate incorporation processes of minorities through an economic lens. Migrant businesses are no longer part of a “niche economy” (OECD, 2010). For example, in many districts of the Ruhr Area migrants support not only local service supply structures but also operate in sectors like handcraft, manufacturing, and business services. What are the limitations and potentials of the economic strengths of migrant businesses in the Ruhr Area? Does the Ruhr Area possess adequate policies to use, support, and develop these potentials? Can transfers from the Ruhr Area to Istanbul and vice versa be made in this respect?

2. Diversification of Migration

Up to the 1980s migration was often perceived as being permanent and unidirectional (migration for settlement). An increasing body of literature in the social sciences and humanities, however, has recently shown that migratory movements are much more diverse and complex in nature: circular migration—short term expatriation as well as return migration or remigration—has substituted the binary model of migration processes (Brickell and Datta, 2011; Constant and Massey, 2002; Dustmann et al., 1996; Glick Schiller et al., 1992; Lundholm, 2012; Dick and Reuschke, 2012; Reuschke, 2010; Salzbrunn 2008; Samers, 2010; Steinbrink, 2009). The diversification of migration is due to various factors: the ongoing division of labor, the globalization of capital and labor along with the emergence of knowledge-based economies, demographic factors that lead to global care chains, climate changes, civil wars, etc. In urban areas, economic shifts have led to a concentration of service sector jobs at both ends of the qualification and income spectrum, which has attracted an influx of people to many countries in the Global North. However, there is also important South-South migration as well as increasing North-South migration, in particular following the economic crisis that started in 2007–2008. Although migration increases social and economic inequalities in most sending countries, contemporary migration is facilitated by improvements in transportation and communication technology and is accompanied by changing social norms and attitudes regarding gender, mobility, and employment. Currently, half of the migrants in Europe are female, but European policies tend to overemphasize family migration without considering independent female labor migration (Salzbrunn, 2010), which has a long history in both the Ruhr Area and Istanbul.

While circular migration means that people circulate between different locations more or less frequently, recent research argues that people have not become ‘rootless’ but tend to develop multiple place identities (Brickell and Datta, 2011) or notions of multiple belonging (Yuval-Davis, 2006). They are in touch with their fellow diaspora, community, or network members in person or virtually. Most people with multilocal (or translocal) living practices and belongings develop a number of ties of differing strength and intensity to several places. Their locally anchored social networks in different places/countries may be autonomous or connected. Hence, a network-based concept has emerged, which is not tied to only one place (Rainie and Wellman, 2012). However, after a tendency to overemphasize networks and nomads,2 most recent studies have convincingly argued in favor of ‘relocating’ migration (studies), as migrants strongly influence the urban spaces in which they reside and not only their countries of origin (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2011; Salzbrunn, 2011). This linking of migration and urban studies is partly due to autocritiques by key authors in transnational studies.

The concept of transnational migration (Glick Schiller et al., 1992, 1995; Levitt et al., 2003; Mahler, 1998) departs from a severe critique of the binary conception of emigration and immigration. It applies a multidimensional and longitudinal perspective on migration processes. Transmigration is generally defined as a “process by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement” (Basch et al., 1994, p. 6). During the last 20 years, the concept has been successfully fine-tuned by scholars all over the globe and across...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Economies of Urban Diversity: An Introduction

- Part 1 Theoretical and Conceptual Insights

- Part 2 Population Flows Affecting Istanbul and the Ruhr Area

- Part 3 Legal and Institutional Frames of Ethnic Entrepreneurship

- Part 4 Residential Segregation and New Inequalities

- Notes on Contributors

- Index