- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Comitology is the most important form of multi-level governance in the EU. Member State and Commission actors together create roughly 2, 500 executive acts per year amounting to half of all European laws. Using new European and national data, this books argues that its accountability has improved over time, but that unexpected gaps have emerged.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Controlling Comitology by G. Brandsma in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Droit international. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Hidden Power

Introduction

Each day, thousands of national civil servants travel to Brussels from all over the European Union: sometimes for consultation, such as when the European Commission asks for expert advice before sending a legislative proposal to the Council of Ministers and to the European Parliament (EP) (Larsson, 2003a); and at other times to work out agreements amongst each other before the Council legislates (Fouilleux et al., 2005) or to deal with executive measures drafted by the Commission (Blom-Hansen, 2011a, 2011b).

When speaking of the European Union, its institutions immediately spring to mind. The European Commission, the European Parliament, the Council of Ministers and the Courts are all well-known actors; they are in the spotlight of the European Union, so to speak. What goes unseen, however, is how deeply involved backstage actors are in the decision-making processes. Although operating on the political sidelines, these hidden actors have a marked impact on the majority of Union decisions, including those concerning very salient political matters.

Backstage Europe is the realm of committees. Van Alphen (Box 1.1) is the official representative of the Netherlands in one of the committees that advises on executive measures drafted by the Commission. This type of committee is part of what is known as ‘comitology’ in EU jargon, and most such committees meet in Centre Borschette, a nondescript conference centre in Rue Froissart, Brussels. All member states participate in comitology committees by sending one or two of their civil servants. The comitology system is specifically designed to advise the Commission on the content of these executive measures: norms, standards, funding schemes and so on. It is a powerful form of advice: in the comitology system, measures proposed by the Commission must first either be voted on by the committee members or they may be vetoed by the Council or the European Parliament on the basis of the committees’ advice. Comitology is a huge system. It is composed of some 220 committees, which discuss and vote on up to half of all European decisions, directives and regulations.1 In this respect, the system produces far more acts than the Council and the European Parliament do legislation.

Box 1.1 Thousands of little decisions

Corné Van Alphen (aged 39) traveled from The Hague to Brussels this morning on an early train. He works as rural development policy advisor for the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture. He cordially greets his colleagues from other countries; most are also policy advisors working for agriculture ministries. Here at Borschette, Europe appears to be run by grade 13 civil servants (intermediate level).

[…]

All proposals are accepted unanimously. Scandinavian farmers can start working with their high-tech ovens. Their colleagues elsewhere in Europe will be paid for maintaining hedges and wooded banks. The civil servants who voted on this leave for lunch.

[…]

Do civil servants like Van Alphen have a lot of power when they are in Borschette? ‘No’, he says. […] ‘But come to think of it’, Van Alphen ponders while prodding his pasta, ‘when you add up all these thousands of decisions that we make across the road in Borschette, which often have a very practical influence, in this case on the future of farmers, well, then it is quite a powerful institution’.

Source: NRC Handelsblad, ‘Een olievlek van ambtenaren’, 14 May 2005.

Backstage Europe and executive rule-making

Massive numbers of little rules

Even though many scholars focus on the legislative practices of the European institutions, the vast majority of European decisions, directives and regulations are, in actual fact, of an executive nature (Van Schendelen, 2010, p. 69–71). Obviously, the aims and principles of policy are embodied in legislation that is adopted by the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament, mostly according to the well-known co-decision or ordinary legislative procedure. But most legislation does not specify in detail who is affected by it and by what means. That is considered to be a matter for the executive. The executive produces a much greater number of ‘little rules’ that come in the form of decisions, directives and regulations and are adopted by the Commission. In short, the legislative acts specify the principles, while the Commission’s executive measures flesh these out into tangible measures, linking these broad policy objectives to specific citizens, companies, regions or states.

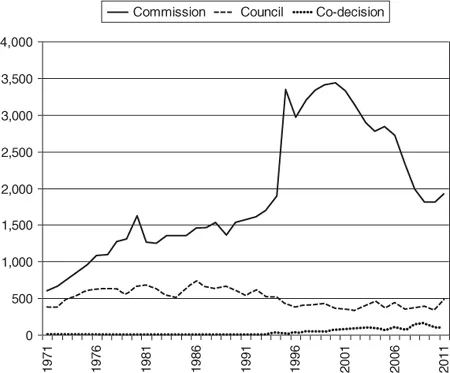

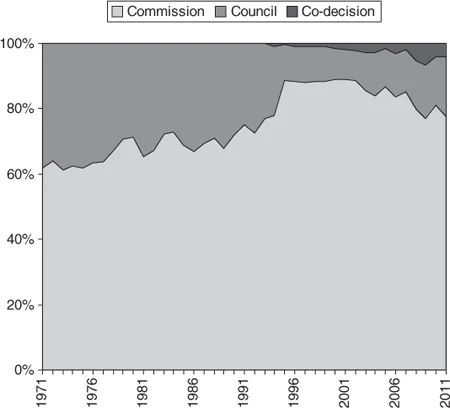

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 are instructive for understanding how many decisions are made in the executive sphere. Figure 1.1 shows the absolute number of decisions, directives and regulations that have been adopted by the three institutions since 1971. In Figure 1.2, the share of each of the institutions in the total is displayed for the same period. Although the legislative co-decision acts receive most attention by far, they only constitute a tiny fraction of the total. Throughout history, the vast majority of European directives, decisions and regulations have been executive acts adopted by the Commission.

Figure 1.1 Acts adopted by the three institutions

Source: EUR-LEX, http://eur-lex.europa.eu, including all Decisions, Directives and Regulations, irrespective of Treaty base, adopted exclusively by the Commission or the Council, or under the co-decision procedure.

Figure 1.2 Ratio between acts adopted by the three institutions

Source: EUR-LEX, http://eur-lex.europa.eu, including all Decisions, Directives and Regulations, irrespective of Treaty base, adopted exclusively by the Commission or the Council, or under the co-decision procedure.

This is also where the executive’s chief backstage actor comes into the picture. Comitology is deeply involved in crafting and negotiating these little rules, and in deciding on who gets what, how and when. Between 45 and 60 per cent of the Commission’s acts first have to pass a comitology committee before they can be adopted. In terms of volume, this makes comitology the most important governance process of the European Union. Next to executive decisions, directives and regulations, the Commission also adopts ‘working programmes’, ‘action programmes’, funding allocations and many more executive measures that are also subject to deliberation in the comitology committees but which do not make it into the Official Journal. In total, the committees have voted between 2,000 and 2,500 times per year over the past decade, which allowed the Commission to adopt about the same number of executive measures, in addition to a smaller number of measures for which no committee opinion was required.2 Hence executive decision-making in the European Union is an important, highly intricate affair, involving a myriad of backstage actors who effectively set their stamp on the majority of all Union acts.

Let’s run through a few examples to show how comitology decision-making relates to political decision-making and how it affects the lives of European citizens. In the Habitats Directive, for example (Council Directive 92/43/EEC), the Council expressed its political will to protect certain species and environmental sites, and established the mechanism that any damage occurring to these must be compensated. But the decisions on which specific species and areas to protect were delegated to the executive, assisted by a comitology committee of national civil service experts in the field of environmental protection. The same can be said with respect to decisions regarding airlines to be put on a black list, the size of tomatoes, safety measures at work, technical standards for trains and railway lines, the safety of toys and many more examples.

Some of these issues may appear to be rather technical, perhaps even boring. But there are plenty of examples where technical matters can be politically quite salient matters. Standards for animal health and animal disease control, for instance, were considered to be political non-issues in the early 1990s, but since the outbreak of BSE they have turned into politically contested issues (Harlow, 2002, p. 70–1). Whether or not specific genetically modified organisms can be released into the environment is also both a technical and a political discussion. These are only a handful of examples out of the thousands of little decisions that together make comitology powerful. Although these particular issues bear much political salience, this is not typical for the bulk of committee activity. Nonetheless, even politically non-salient issues are important. After all, all decision-making comes with winners and losers. To those who are directly affected by new legislation, the devil is usually not in the objectives of legislation but rather in the detail of implementation (Van Schendelen and Scully, 2006, 6).

The power of comitology

Given the technical nature of the issues comitology deals with, it is not surprising that expertise is needed for effective participation. Hence, participants in comitology are usually policy specialists working in national ministries or agencies, who, once in Brussels, take on the role of member state representative. For them, membership of a comitology committee is an international extension of their day-to-day work ‘at home’ (Egeberg, Schäfer and Trondal, 2003, 21–2).

The power of comitology is vested not only in the expertise of its participants but also in the formal position of the comitology committees in the Commission’s processes of adopting executive measures. There are two different modes by which the committee members affect Union policies, which are only briefly discussed at this point but which are looked at more extensively in Chapters 2 and 4. The first mode is based on Article 291 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereafter referred to as TFEU), which provides that mechanisms must be put in place by which the member states can control the Commission’s exercise of its implementing powers. These mechanisms of control are further specified in a Council and Parliament Regulation (2011/182/EU), hereafter referred to as the 2011 Comitology Regulation. Under this regulation, the Commission must present drafts of implementing measures to committees of member state representatives, who are empowered to block their adoption. Depending on the voting procedure used in the committee and the results of the vote, the Commission can either adopt its proposed measure, resubmit an amended version of the same measure to the same committee, decide not to adopt the measure at all, or it can forward the original measure that was blocked by the committee to an appeal body (which, before the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, was the Council of Ministers) (see Council Decision 1999/468/EC, Council and Parliament Regulation 2011/182/EU). Apart from the binding effects of the outcomes of such votes, there is another reason why the Commission needs to secure support from the committees. Since most, if not all, European executive measures are required to be further implemented at the national level, the member states send the same policy specialists to the committee meetings who are assigned to implement those policies at the national level. In practice, therefore, the Commission cannot adopt executive measures swiftly without the formal approval of a comitology committee, let alone ones that are seen as effective. For this reason, the Commission works hard to secure a positive vote in the committees, as testified by the fact that often the same issues are repeatedly put on the committees’ agenda, and by the very low number of negative votes or referrals to the appeal body (Alfé et al., 2009, p. 145).

The second mode is based on Article 290 (TFEU), which applies in cases of ‘delegated legislation’. In such cases, a legislative act grants the Commission the power to supplement or amend ‘non-essential elements’ of existing Council and Parliamentary legislation. This refers, for instance, to amending certain elements in an act’s technical annexes (for example, lists of dangerous substances in directives on safety, lists of endangered species in directives on environmental protection, et cetera). In the very final stages of drafting a piece of delegated legislation, the Commission consults a committee of ‘experts’, which in practice represent the member states.3 The Commission subsequently forwards this draft – together with the committee opinion – to the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament, both of which are also kept informed of all committee proceedings. Once the delegated act is finalized and forwarded, both the Council and the Parliament may oppose it and thereby block its adoption, or even revoke the delegation of legislative powers to the Commission completely (Article 290 TFEU, European Parliament, Council of Ministers and European Commission, 2011). Since the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty, in a formal sense these committees have become part of the Commission’s expert group system (see Chapter 4), which is why, in a very strict legal sense, they are no longer part of comitology, even though their members are made up of the same people and the committees may still vote – albeit not with binding effect (European Commission, 2010a, 15).

The fact that the system currently consists of two modes is the result of a protracted inter-institutional battle between the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers. Historically, the European Parliament had very little influence on the functioning of the comitology system; however, with the entry into effect of the Lisbon Treaty, a delegated legislation regime with extensive control rights for the European Parliament and no formal role for committees was introduced. This led some commentators to argue that in the new situation, reference should be made to delegated and implementing acts rather than comitology (for example, Peers and Costa, 2012). Others continue to speak of comitology, while taking into account the differences between the two newly introduced regimes (for example, Hardacre and Kaeding, 2011; Héritier et al., 2012, p. 134). Because the origins of the two systems are related, because both operate as mechanisms for controlling the European Commission’s activities and because both systems include committees of member state representatives, this book embraces the latter view, referring to these two together systems when speaking of comitology or of committee members. Obviously, however, the fundamental differences between the two systems are detailed throughout this book.

Comitology, accountability and democracy

The irony of accountability

Formally speaking, comitology participants act as delegates of the national administrations. They would therefore be expected to bargain with the other member states’ representatives and the Commission in order to favour their own national interest as much as possible. However, much of the available evidence suggests that there are many cases in which committee meetings are not characterized by intense negotiations but rather by a more deliberative form of interaction. This phenomenon, termed ‘supranational deliberation’ (Joerges and Neyer, 1997a), implies that committee members tend primarily to search for the common good from a professional point of view (see Joerges and Neyer, 1997a; Pollack, 2003a). In the eyes of many participants, finding the best technical solution would appear to be more important than advancing their own national interests. The meetings are characterized by a spirit of expertise, scientific evidence plays a prominent role, and formal power seems to be of minor interest (Wessels, 1998, 225; Sannerstedt, 2005, p. 105).

No matter how sound the results produced by the comitology system may be ( Joerges, 2006), concerns have been voiced as to the degree to which comitology is an accountable form of governance (Radaelli, 1999, 770–1; Schäfer, 2000, p. 22–3; Harlow, 2002, p. 67–71; Rhinard, 2002, 196–203; Van Schendelen, 2006, 37). Comitology is concerned with fleshing out the details of well over 2,000 measures per year. On the basis of its input, the Commission may decide to draft a measure in a particular way so that it can be sure of its acceptance once the matter is voted upon in a committee under Article 291 (TFEU) or after it is forwarded to the other institutions under Article 290 (TFEU). The number of times issues appear and re-appear on the agenda of committee meetings means either that the Commission anticipates what is acceptable to a majority of the committee, or that it is deliberating with the committee members in a consensual way, in order to find an optimal outcome together (Alfé et al., 2009, p. 145–6). In both interpretations, comitology effectively acts as decision-maker for a wide range of policy issues, and hence should also be able to be held accountable.4

Yet the irony of comitology is that it was designed to be a control device in itself. When the first common policies were to be implemented in the early 1960s, the member states in the Council feared that they would not be able to control the Commission when it exercised its executive powers. The comitology system was created as a means to mitigate this risk. By obliging the Commission to present its executive proposals to a comitology committee consisting of member state representatives, the Council aimed to keep the Commission in check for matters where it felt such special obligations were necessary (Bergström, 2005, p. 43–57; Blom-Hansen, 2008, 2011b, p. 53–71).

Increasingly, however, concern about the accountability of comitology has been voiced. Comitology involves a large number of civil servants, and the member states can send their people to the committees, whereas the European Parliament – as co-legislator to the Council – seems barely involved (Neuhold, 2001; Bradley, 2008). The meetings are only attended by the relevant specialists (Joerges and Neyer, 1997a) and are not held in public (Neuhold, 2001). Minutes – insofar as they can be traced on the Internet – are either uninformative or incomprehensible to outsiders (Brandsma et al., 2008). And, last but not least, comitology produces most of the detailed regulations, directives and decisions for which the European Union is renowned, including the recently repealed regulations on quality standards for bananas and cucumbers of different lengths and shapes.5

Comitology and the democratic deficit

Many of the reasons for which citizens tend to dislike European governance also seem to apply to comitology en miniature. This raises questions as to the democratic quality of comitology decision-making. Does the often-cited ‘democratic deficit’ of the European Union manifest itself in backstage Europe too? Even though there is no consensus on what the term ‘democracy’ actually means within th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Hidden Power

- 2 Comitology: The System, the Committees and Their Participants

- 3 Accountability and Multi-Level Governance

- 4 System-Level Accountability: Conflict Over Control

- 5 Committee-Level Accountability: System Meets Practice

- 6 Participant-Level Accountability: Substantive Talks and Deafening Silence

- 7 Comitology and Multi-Level Accountability

- Annex: Overview of Sources Regarding the Post-Lisbon Negotiations on Comitology

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index