- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

What role do independent institutional investors play in the corporate governance of listed German companies? The authors provide insight into an empirical and qualitative research study, exploring the importance of communication and the role, independence and expertise, responsibilities, influence and monitoring of institutional investors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Role of Institutional Investors in Corporate Governance by P. Nix,J. Chen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Communication. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1. Research background

In recent years, corporate governance has emerged as a critical business issue and has attracted public attention for various reasons.

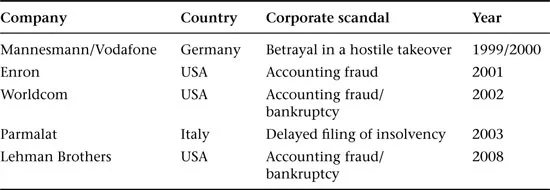

Firstly, a number of shocking, high profile corporate scandals and the unexpected failure of several major companies in the Western Hemisphere at the beginning of the twenty-first century, as well as the negative outcome of the financial crisis, have fuelled current discussions on good governance. Table 1.1 gives a brief overview of those scandals and the respective results of bad governance.

An event that had a significant impact on the development of corporate governance in Germany was the takeover of the telecommunications and engineering Mannesmann Group by Vodafone, the UK mobile phone company. After three months of an unfriendly takeover battle, the boards of both companies reached a merger agreement. Shortly after the announcement of the final takeover deal, it became public that some of the top managers had negotiated a ‘golden handshake’. The merger was followed by a criminal trial, which began on 21 January 2004. The legal issues involved were whether or not former directors of Mannesmann had committed ‘Untreue’, or breach of fiduciary duty. The six defendants included prominent figures in corporate Germany, most notably Josef Ackermann, the former chief executive of Germany’s largest bank, Deutsche Bank, and former members of Mannesmann’s supervisory board (Aufsichtsrat). The enormity of the companies and personalities involved stretched the trial’s magnitude beyond the confines of this single takeover (Kolla, 2004). This takeover deal was regarded as a sign of the ‘end of the Deutschland AG’. The long-term, consensus-oriented German approach has often been contrasted with the ‘Anglo-Saxon approach’. The Mannesmann case marked an important step towards a more shareholder value orientation and an acceleration of the transformation process in the German governance system (Jürgens et al., 2000).

Table 1.1 Selected corporate governance scandals

Source: Petra Nix.

Investors lost confidence in companies, their managers and in the numbers recorded by them after the fraud committed by Enron and Worldcom. Both companies used inappropriate accounting practices to appear profitable in order to attract investors. An audit revealed that Worldcom’s cash flow was overstated by $3.9 billion1 (Backover et al., 2002). Both cases forced investors, lawmakers, executives and regulators to review the system that allowed such disasters to occur.

Parmalat, the biggest dairy company based in Italy, declared bankruptcy for many reasons, including investment disasters, non-existent cash in bank, fake transactions, hidden debts and the use of derivatives and accounting fraud to hide these facts (http://emievil.hubpages.com/hub/ 10-Scandals-That-Rocked-the-Accounting-World, accessed 25 February 2012).

The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers is widely acknowledged as the starting point of the worldwide financial crisis. On 14 September 2008, the investment bank announced that it would file for liquidation after huge losses in the mortgage market, and a loss of investor confidence crippled it, and it was unable to find a buyer (http://topics.nytimes.com/top/news/business/companies/ lehman_brothers_holdings_inc/index.html, accessed 25 February 2012). The behaviour of the company resulted in socially unacceptable costs, and its collapse is acknowledged as the consequence of a financially and morally bankrupt institution, which failed its fiduciary duties and betrayed both public and private trust (http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/cifamerica/2011/dec/12/lehman-brothers-bankrupt, accessed 25 February 2012).

Corporate governance in the UK was influenced even earlier by financial malpractice in companies, such as Brent Walker, Polly Peck and the Maxwell Corporation in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In the corporate financial crisis in 2002, CEOs at 23 US firms under investigation took home $1.4 billion from 1999 to 2001. However, at the same time, these companies had laid off 162,000 employees, and the value of their shares had fallen by $530 billion – about 73% of their market value.2 The magnitude of the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, however, was even bigger. Through the Trouble Asset Relief Programme (TARP) and the Capital Purchase Program, the US government had a net position of $134 billion in the banking sector, $75 billion in the automotive industry and $70 billion in AIG. Mervyn King, governor of the Bank of England, estimated that UK taxpayers had provided direct or guaranteed loans and had made equity investments just short of a trillion pounds or almost two-thirds of the UK’s annual GDP (ECGI, 2009).

Secondly, there are a number of controversial issues in corporate governance. Among these are pay policies, checks and balances, the separation of power in the management of public companies, diverse and remote shareholders, shareholder value versus stakeholder value, corporate risk assessment, short-term profit orientation versus long-term value creation, board assessment, board effectiveness, board independence and aligning the interests of managers, directors and shareholders.

Thirdly, in the last decades, the discussion of corporate governance has been emphasized in corporations, the academic literature and in public policy debates. After the corporate scandals in 2001 and 2002, new laws and guidelines have emerged, especially for listed corporations. However, not all of them have been able to prevent the irrational exuberance of the US real estate market in 2008, which was followed by a short but severe financial and economic crisis.

2. Corporate governance in general

Various definitions illustrate what corporate governance is; however, the term ‘corporate governance’, which was not used until approximately 25 years ago (Tricker, 2009), still does not have an adequate explanation (Gerum, 2007). To incorporate governance in a broader context, definitions from the Anglo-Saxon, as well as the European perspective, have to be taken into account. They emphasize different aspects of corporate governance, such as a shareholder versus stakeholder approach, power, confidence, responsibility, accountability and trust, and the interest of the company, among others. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) define corporate governance as the means by which a firm’s outside investors try to ensure that senior managers within the firm do not exploit them. This narrow definition relates to just one stakeholder group, the shareholders. Demb and Neubauer (1992) see corporate governance as the process by which corporations are made responsive to the rights and wishes of stakeholders. The internal dimension of corporate governance relates to internal control and board structure, whereas the external dimension relates to aspects, such as the role and influence of national and international independent institutional investors. This research focuses on the external perspective.

3. Corporate governance in Germany

Empirical research has shown that countries have an influence on the developments in corporate governance (Chizema and Buck, 2006; Rajan and Zingales, 2003; Light et al., 2004; Zattoni and Cuomo, 2008; Monks and Minow, 2009). Germany is a ‘latecomer country’ regarding corporate governance. In contrast to other countries, a code of corporate governance for German firms was regarded as unnecessary for a long time, because the essential aspects of governance (e.g., the separation of management and supervision) were required under German law (v. Werder et al., 2008). Today, German listed corporations are obliged to follow the German Corporate Governance Code (DCCG). Therefore, the code has a certain impact on the corporate governance behaviour of corporations since companies initiated changes. Compared to the codes of other countries like the UK, the German code gives different recommendations regarding the requested shareholder involvement in corporate governance. In the UK, there is a clear emphasis on the role of the investors (Mallin et al., 2005), but the German Corporate Governance Code does not go that far. It only stipulates that it is ‘to promote the trust of international and national investors’ and that ‘shareholders exercise their rights at the General Meeting and vote there’. The code does not provide further recommendations regarding the role of the investors in corporate governance. It focuses more on the internal aspects, like the cooperation between the management board (Vorstand) and supervisory board (Aufsichtsrat), and the formation of committees, but it does not stipulate the ongoing relationship between shareholders and the corporation.

4. Institutional investors

Institutional investors are organisations that pool large sums of money and invest those sums in companies. They can play an active role in corporate governance. According to Bassen (2002), investors can be categorized as private, entrepreneurial or institutional investors. A key point is that international institutional shareholders are motivated primarily or exclusively by financial returns rather than by the ‘private’ benefit of control, such as social status (Pendleton, 2005).

Proportions of equity held by institutional investors – pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds, endowments, private equity and mutual funds – are rising across all OECD countries. Meanwhile, German and international institutional investors are becoming more influential in corporate governance, even in bank-dominated countries like Germany, inter alia due to international investments, pension reforms and the European Monetary Union (EMU). The growth of institutional investors has been dramatic in most industrialized countries; therefore, they have become an important factor in capital markets. This is also true for Germany, where total equity assets grew by 33% annually between 2000 and 2005. In the same time span, the number of institutional investors has grown from 53 to 164 (Ferreira and Matos, 2008). Additionally, the shareholder structure of German listed companies is more international and more diversified than a decade ago. Pendleton (2005) differentiates between two kinds of investors, insiders and outsiders. Insiders are large bloc holders, families and cross-owners, while outsiders are institutional investors. This study focuses on outsiders, i.e., German and international institutional investors who can, but do not need to be a major shareholder. The terminology ‘institutional investor’ implies German and international institutional investors and is used consistently throughout this book, if not stated differently.

5. Framework of research

The purpose of this research is to investigate the role of international institutional investors as owners of public companies in Germany. On the basis of an empirical study, it aims to provide information regarding the influence of institutional investors in listed companies. Moreover, it examines how institutional investors exercise their role in corporate governance apart from official votes execution in the AGM’s and unfriendly shareholder activism.

Since the 1990s, a large body of corporate governance research has emerged. Most of the existing corporate governance research on boards and corporate governance has a US-inspired deductive approach, driven by the ‘publish or perish’ syndrome that dominates the US academic community (Huse and Gabriellson, 2004). Doctoral students and scholars in tenure track positions conducting research using easily available data. The usual board measures employed in these studies are CEO duality, insider/outsider ratio, the number of board members and the share ownership of directors (Finkelstein and Mooney, 2003; Johnson et al., 1996). Since 2001, a more multi-theoretical approach to the board strategy debate has been emerging, in which studies and academic research have shifted from a general analysis of the principal–agency theory to the nature and role of owners.

In the research of selected journals,3 the findings were as follows: In 68% of the academic articles, the agency theory was used as the theoretical framework; more than half of the research (66%) was about common law countries like the USA and UK; the most popular topics were compensation, firm performance and managerial behaviour, and almost three-quarters of the articles were based on archival data. Only 7% used surveys and interviews as a research method and ‘investor’ as a topic.

However, the theory that institutional investors of publicly quoted companies are the best ones to carry out, or at least to supervise, the functions of corporate governance has distinct characteristics and limitations (Hadden, 1994; Mallin et al., 2005; Mintz, 2006; Hirschman, 1970; Webb et al., 2003, Hellmann, 2004). There is a strong need for more field research that captures the role of institutional investors in governance oversight and how boards and managers make decisions (Anderson et al., 2007). Therefore, more insights into the role of institutional investors that go beyond the publicly available data are needed. Empirical studies that focus on the role of international institutional investors in the corporate governance of German listed companies could not be found.

In the academic literature, the expectations regarding the role of institutional investors in corporate governance are quite clear regardless of the controversy surrounding it. Ferreira and Matos (2008) found that institutional investors have a strong preference for firms with good governance and that firms with higher ownership by foreign and independent institutions have higher firm valuations, better operating performance and lower capital expenditure. Furthermore, their results indicate that institutions with fewer business ties to firms are involved in the monitoring of the corporation.

I have over 20 years of experience as investor relation officer and consultant to listed German and international companies in developing, building and maintaining their relationship with international institutional investors. Furthermore, I have conducted empirical research regarding investor relations and corporate reporting in Germany and Switzerland. This has given me a broad knowledge base of the development of corporate governance and the relationship between public companies and their institutional investors.

The research is based on the principal–agency theory, since this theoretical framework helps to understand a firm’s relation to its equity stakeholders. It aims to understand the viewpoints of the corporate managers of listed companies and how institutional investors use their opportunities to monitor and influence German listed corporations.

Based on the literature review, this study attempts to answer the following research question:

• ‘What is the role of institutional investors in the corporate governance of German listed companies?’

The answer can be used to formulate a number of hypotheses or propositions about the role of independent institutional investors in the corporate governance of German corporations.

Based on the research findings on institutional investors, this role is carried out through the investor’s chance to make an impact by monitoring and/or influencing German companies. The influ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Fundamentals of Corporate Governance

- 3. Methodology

- 4. Description of Interview Partners and Categories

- 5. Study Results

- 6. Study Findings and Analysis

- 7. Conclusions and Implications

- Appendix

- Notes

- References

- Index